Organizing Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Next>>

Organization of Ship's Food In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 14

Officers In Charge of Food - Quartermasters on Legal Voyages

On navy ships, the quartermaster was a petty officer, someone greater in rank than a normal sailor but below officers and warrant officers. The duties of this role shipboard were not well defined in the navy in the 17th century.1 Even as late as the publication of the 1731 Regulations and Instructions of the English navy, quartermasters are not mentioned, suggesting that their roles were not well-defined officially.

Conning the Ship Using a Whipstaff,

From Ships and ways of other days,

By E. Keble Chatterton, p. 189 (1913)

Nathaniel Boteler gives a brief description of the quartermaster's role which focuses on his involvement in victualling in the navy. "The particular Duties of the Quarter-masters (whereof there are more or fewer, as the Ship is of Burden) are to rummage in the Hold of

the Ship, upon all Occasions; to accompany and overlook the Steward in delivery of the Victuals to the Cook, and in his pumping and drawing of the Beer; and to take care in general, that there be no abuse nor wastes committed in any of those Services: they are likewise employed in the Loading of the Ship."2

A broader description of the quartermaster's duties in the navy is found in the manuscript collection of Hans Sloane, which repeats Boteler's points and adding:

They are also to keep their watches when the ship's company is quartered [dividing the crew into four quarters, each standing a watch] every quarter being to have one quartermaster at least in their watch, whether it be a quarter watch when the ship is in harbour and at anchor or half watch when it is at sea and in foul weather. These quartermasters are also to take their turns in the cunding [conning] of the ship, and to look to him at the helm that he be diligent in his steering, and to suffer none to be idling in the steerage that may disturb him and make him careless of his hand. To which end some of them are continually to keep a station upon the quarterdeck or half deck or at the round-house door or wheresoever they may best look to him at the helm and direct him3

Artist: Nicolas Ozanne

Preparing to Load Supplies, The Port of Bordeaux,

Seen from

the

Wheat Dock (1776)

From this description can be seen the origin of the title. Of course, none of that concerns food. As Boteler explained, the quartermaster would be involved in loading and retrieving victuals from the hold as well as overseeing the ship steward's delivery of victuals to prevent waste. Although Boteler's description dates to the first half of the seventeenth century, a letter written by the victualling board almost one hundred years later indicates that the responsibility for moving the food was that of the ship's master, "who seldom... [take] the trouble they ought in this particular, but leave it to their mates, the mates to the midshipmen, and the midshipmen to the quartermasters."4 While the master might be said to be responsible for moving food, Boteler's description suggests it more traditionally rested upon the quartermaster.

A third part of the quartermaster's job touched upon victualling. He represented the men's concerns to the officers in the English navy, which included matters of victualling. In a court held before Francis Drake regarding a mutiny aboard the Golden Lyon in 1587, Captain John Marchant said that a quartermaster gave the captain a letter from the company complaining about (among other things) a lack of food, "for our allowaunce is so smale we are not able to lyve any longer of it; for when as three or foure [men] were wonte to take a charge in hande, nowe tenne at the leaste, by reason of our weake victuallinge and filthie drinck"5.

In addition to being on navy vessels, quartermasters were sometimes found on merchant ships. Merchants were concerned about keeping the cost of a voyage down, so they sometimes forwent the role, relying instead on stewards and/or cooks to handle anything concerned with victualling. Still, some merchant ships had quartermasters, particularly the larger ones. Perhaps the most common example of this can be found in the policies of the East India Company (EIC) ships.

The 1621 EIC Standing Orders stated that Quartermasters were to "diligently attend aboard the Companies Ships every day, to see all the victuals, provisions, stores, and Merchandize, orderly stowed in places fit and convenient, and they shall not suffer any thing to be laden into the Shippes hold, before the Purser or his Mate have taken a true note thereof."6 Quartermasters were picked from 'the more experienced' foremastmen on an East Indiaman, and could steer the ship like their naval counterparts.7 Not surprisingly, this description emulates some of the navy quartermasters' duties. Cyril Northcoat Parkinson says that an East Indiaman had six quartermasters8, while Peter Earle says there were five9, although this likely varied based on the burden of the ship and the time period under consideration.

Quartermasters regularly appear in another type of merchant, the slave ship. Captain

Photo: Karunakar Rayker

'Cuz for Some Reason, THAT Seemed Like a Good Idea,,,

Thomas Philips mentions that a tiger which had been given to him was somewhat inexplicably being kept in a cage on his ship Hannibal. The tiger escaped and decided to chew on a woman's calf. "[A]s soon as one of our quarter-masters perceiv’d [what had happened], he ran to [the tiger], and giving him a little blow with the flat of a cutlass, the tiger couch’d down like a spaniel dog, and the man took him up in his arms, dragg’d him along, and without any resistance or harm, pent him up in his coop again."10 While the tiger is the most sensational part of this story, it is interesting that Philips suggests the ship had more than one quartermaster aboard, possibly copying either the navy four man system or the EIC five and six man system. Slave ships were generally more heavily manned than other merchant ships (excluding East Indiamen) which may explain the large number of quartermasters. Unfortunately, Philips doesn't provide much more information about such men or their role on his ship.

Woodes Rogers also had quartermasters on his 1708-1711 privateer voyage which travelled along the South American coast, across the Pacific and back home to England. In keeping with the navy system, four quartermasters are mentioned being aboard his ship the Duke including John Johnson, Thomas Young, Charles Clovet, and John Bowden.11 The companion ship which left England with the Duke also had at least one quartermaster, James Stratton, who is mentioned when he was shot in the thigh during an engagement with the Spanish in April of 1709. Stratton appears to have survived the wound.12 It is almost certain that this vessel also had four quartermasters, despite their not being mentioned. Once again, nothing is said of their responsibilities on the voyage, although they would presumably have been similar to those of quartermasters on a naval voyage.

1 Dr. Richard Blakemore, 'Roles on Board Merchant Ships during the Seventeenth Century', University of Exeter Website, gathered 9/23/21; 2 Nathaniel Boteler, Colloquia maritima or Sea Dialogues, 1688, p. 18-9, See also William Monson, The Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson, Vol. IV, M. Oppenheim, ed., 1913, p. 20; 3 'Shane MSS, 2449, f- 20', William Monsons Naval Tracts, Vol. IV, Oppenheim, 1913; 4 Daniel A Baugh, Naval Administration 1715-1750, 1977, p. 411; 5 Michael Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, 1896, p. 384; 6 East India Company, The lawes or standing orders, 1621, p. 46; 7 Jean Sutton, Lords of the East, 1981, pp. 86 & 113; 8 Cyril Northcoat Parkinson, The Trade Winds, 1948, p. 148; 9 Peter Earle, 'The Origins and Careers of English Merchant Seamen in the Late Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries', The Social History of English Seamen, 1650 -1815, Cheryl A Fury, ed., 2017, p. 138; 10 Thomas Phillips, A Journal of a Voyage Made in the Hannibal, A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol VI, Awnsham Churchill ed, 1732, p. 230-1; 11 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 7; 12 Rogers, p. 188-9

Food Storage on a Ship

As mentioned in the discussion of the location of the ship's steward, food ready for immediate or near-term use would have been kept in the steward's room, which was typically located on the orlop deck (one just above the hold) on larger ships.

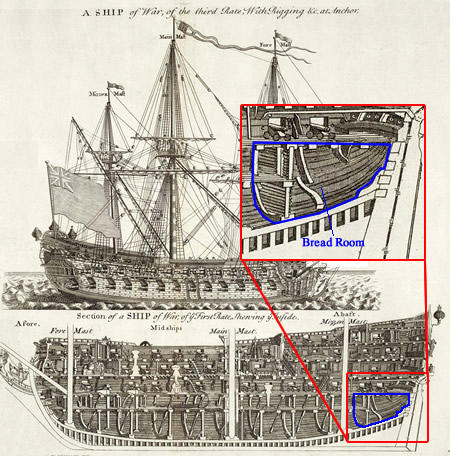

Location of the Bread Room on a Third Rate Warship According to a Labeled Sectional

Image From Ephraim Chambers' Cyclopedia, Vol. 2 (1728)

Interestingly, former pirate and navy vice-admiral Sir Henry Mainwaring wrote in 1644 that the steward's room was "that part of the Howld, wherein the Victuals are Stowed"1, indicating that the purser's room was in the hold when he sailed in early part of the seventeenth century. However, by the construction of the 1673 ship establishment, ships of all rates were built with the steward's room located in on the orlop deck. Since it would have been impossible to store all the food required for a long voyage in this small room, the majority of victuals were kept in the casks in the hold particularly on a large ships making long voyages.

Bread was kept nearby in the bread room on naval vessels with the desire to keep it from getting wet. As Sieur Gullet explained in 1705 that the bread room was necessary to keep the biscuit "preserv'd Safe, and Dry."2 This was located in the aft of the ship, occupying both the orlop deck and the hold as seen in the image at left. Measures were taken to keep this room from getting wet. Captain John Smith wrote that in the early part of the seventeenth century, "The Bread-room is commonly under the Gun-room, well dried or plated."3

Although the purpose of lining the bread room with metal plating is not made explicitly clear by John Smith,

Artist: Charles Brooking -

East Indiamen in a Gale (mid-18th century)

it was an attempt to keep water from penetrating the room. In the early 1670s, several pursers testified to the value of lead sheathing on naval vessels including the first rates Royal Prince and St. George, second rate Royal Catherine, third rate Fairfax, fourth rates St. David and Happy Return4. Lead-lining was clearly a widely used technique for protecting the bread based on the variety of ship ratings on which it was employed. In addition to protecting the bread room from dampness, it may also have been an attempt to protect the room during battles since gunpowder was sometimes stored there. In the encounter between the East Indiaman Dorrill and Ralph Stout's pirate crew of the (former East Indiaman) Mocha in 1697, the Dorrill received "two 'great shot' [cannon balls] in the bread room which caused us to make [take on] much water and damaged the greatest part of our bread”5 .

Historian Brian Laverly discusses several other measures taken by the navy to keep the bread room dry. He explains that the bread room was placed on "the frame timbers high above the keel, so that there was relatively little danger from bilge water. ...the bread room extended above the orlop deck, at which level gratings were sometimes placed for the bread to lie on. The

Artist: Thomas Philips

The Room in the Hold at the Back, Section Through a First Rate Ship (c. 1690)

Note that there is a scuttle cut behind the gun above the room, which is similar to that described

by Brian Laverly for entering the fish room. However, there also appear to be doors on the

Orlop Deck. Laverly explains, "On early ships the bread room continued all the way to the

transoms of the stern." (p. 189)

bread room was, according to an order of 1686, to be double lined with dry seasoned slit deals [light wooden boards]."6 He says that in 1715, "it was decided to floor the bread room which would be protected from damp using flooring 'made in the nature of hatches, to lay loose, so as to be taken up without tearing them to pieces, whenever there is occasion to clean and water passages under them, to give air and search these parts.'"7.

Direction was also provided for maintaining the bread room and its contents in June of 1715. The Victualling Board sent the Admiralty Secretary directions for ships sailing to overseas locations which didn't have established land-based victualling agents because of 'very irregular proceedings' which were occurring. Among these instructions, the Board explained that when revictualling a ship, the "biscuit which may remain on board, [must] be bagged up, and the bread room cleaned, aired and secured in the best manner possible."8 Keeping the bread room clean would have helped keep insects and other vermin away from the biscuit.

Fish was sometimes stored in a separate room in the hold as well, albeit for an entirely different reason than bread. Laverly says that fish was kept in a special room in front of the bread room

and

Edward Low's Men Drinking, From Histoire der Engelsche Zee-Roovers (1725)

behind a solid partition wall in order to separate it from the other cargo and contain the smell. The entryway was a scuttle hole in the floor of the orlop deck. He includes diagrams of the second rate HMS Ossory (1711) and third rate HMS Resolution (1708) which indicate the position of a fish room near the aft of the vessel.9

Other rooms related to food storage might be specified on larger ships including officer's storerooms and a spirit room for storing alcoholic beverages the navy provided to the crew (these sometimes included brandy and rum). The purpose of such a spirit room was almost certainly primarily to protect the spirits from theft by the men.10 Laverly explains that "the increasing use of spirits [as opposed to beer and beverage wine] in the second half of the eighteenth century made it necessary to create a space where they could be kept safe."11 With this comment in mind, when a 'spiritous liquor room' was present on navy vessels during the golden age of piracy, it would have been found primarily near the end of the period.

While the above-mentioned rooms were designated for specific victuals on navy ships, most of the food was just stored in the hold. Laverly says that the hold was basically divided into two parts: the fore and after holds.

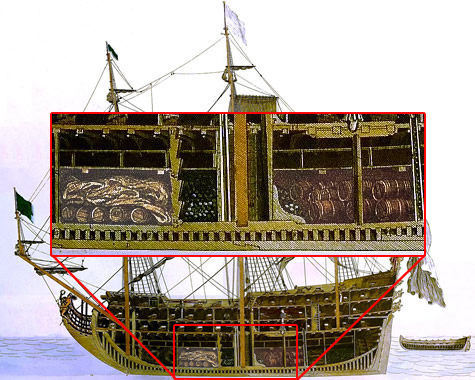

Artist: Thomas Philips - Fore and After Hold, Section Through a First Rate Ship, Possibly HMS London (c. 1690) |

Cask Hold Storage on a French Warship, From Coupe d'un trois-ponts français de 104 canons,

By

Henri Sbonski (c1690)

Writing before the golden age of piracy, Henry Mainwaring said that the hold was "where all our victuals, goods, and stores do lie"14. Laverly adds that the "main hold was used for provisions such as water, meat, beer, cheese and butter which required neither special care nor security."15 Such victuals were kept in various-sized casks, with the largest and heaviest (those containing water and beer) making up the bottom tier. The bottom quarter of these large casks were surrounded by shale ballast, which was required to maintain proper ship buoyancy. The beer was so problematic because of the space required to transport it, the Victualling Board suggested in 1717 that their Lisbon Victualling Agent supply ships with four months of beverage wine so that the ships didn't have to carry so much beer to the Mediterranean with them.16 Once water and beer casks were loaded, other, smaller casks were loaded on top of them in tiers with the smallest casks being loaded around them to optimize the space.17

Since quartermasters were concerned with both the proper storage of victuals before the voyage and its correct retrieval during it, they would have interested themselves in how food was stored and retrieved.

Photo: Murat Ozsoy - Moving Casks, Vasa 64 Gun Swedish Warship Model

In June of 1715 the Victualling Board sent the Admiralty Secretary instructions outlining the importance of managing victual stowage and retrieval. They ordered that "all possible care be taken in the stowing the provisions on board his Majesty's ships, as well for the preservation of the same from any accidents of perishing or embezzlement"18. They later added, "due care [must] be taken in stowing or rummaging the hold that the cask be not knocked against each other or the ship's sides"19. The same order also mentioned that victuals in the hold should be organized so that the oldest victuals could be retrieved first since they were the most likely to spoil. There was a lot to consider when stowing and retrieving casks of food from the hold.

Related to this was concerns about a ship's 'trim' (the difference between the forward and aft draft). The weight distribution in the vessel's hold directly impacted the way it sat in the water. Writing about merchant vessels, Peter Earle explains that "accessibility [of food and cargo in the hold] was weighed against the need to keep an even trim, while care was taken that the cargo would not shift once the ship inevitably began to pitch and roll."20 He adds that skill and forethought were required to properly load a vessel.

Much thought was given to the matter of food and beverage vis-a-vis the ship's trim on long voyages. George Shelvocke dryly commented

Photo: Wiki User Musphots - 400 Ton 17th Century Merchant Ship Section Model

than when his vessels left England in 1719, they "were incumber'd only with provisions, [but] we should in a little time eat and drink her into a better trim"21. Historian Janet McDonald advises modern readers to consider "the weight of provisions and beverages that had to be carried, and the not inconsiderable weight of the casks themselves (aka. tare weight), and you can appreciate the magnitude of the problem."22 In addition, as food and water were consumed, they usually had to be replaced (despite what Shelvocke says). "Consume too much of the hold's contents and the ship will lighten and rise in the water, becoming, since she carries a lot of weight in her guns, top-heavy and at risk of capsizing in rough weather."23 To offset this, as food was consumed, the emptied casks were filled with salt water to balance and maintain the trim.24

1 Henry Manwaring, The sea mans dictionary, 1670 (1644), p. 101;2 Sieur Guillet, The Gentleman's Dictionary, 1705, not paginated; 3 John Smith, Seamans Grammar and Dictionary, 1691, p. 12-3; 4 Thomas Hale, An account of several new inventions and improvements now necessary for England, 1691, pp. 83-5, Thanks to Matthew Brenckle for pointing me to this resource; 5 Solomon Lloyd and William Reynolds, “Letter from Solomon Lloyd and William Reynolds to his Excellency Sir John Gayes &c Freighters of ship Dorrill, dated Achin 28 August 1697”, The Indian Antiquary, George Hill, ed., Volume XLIX, January, 1920, p. 6; 6 Brian Laverly, The Arming and Fiting of English Ships of War, 1600-1815, 1987, p. 189; 7 Laverly, p. 146; 8 Daniel A Baugh, Naval Administration 1715-1750, 1977, p. 411; 9 Laverly, pp. 162 & 189; 11 Janet MacDonald, Feeding Nelsons Navy, 2014, p. 127 & Laverly, p. 189; 1,12,13 Laverly, p. 189; 14 Manwaring, p. 53; 15 Laverly, p. 189; 16 Baugh, p. 421; 17 Laverly, p. 189; 18,19 Baugh,p. 411; 20 Peter Earle, Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775, 1998, p. 69-70; 21 George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 5; 22Janet MacDonald, Feeding Nelsons Navy, 2014, p. 78; 22 MacDonald, p. 79; 24 Earle, p. 76

Officers In Charge of Food - Quartermasters on Illegal Voyages

The duties of the Quartermasters on legal voyages fall far short of their role on extra-legal vessels.

Artist: Amedee Forestier

Fanciful Illustration of a Pirate Crew, They Stopped Only to Drink (1886)

The role of a quartermaster among many of the later buccaneers and all of the pirates was much larger than that found on navy, merchant and even privateer voyages. The captain and the quartermaster basically shared oversight duties with the golden age pirates taking a page out of the buccaneers' book to define the duties of this officer. This should not be particularly surprising given that many of the pirates at the beginning of the golden age were holdovers from the buccaneer era.

Similar to the example of the quartermaster on Drake's voyage in the previous section, the quartermaster was elected by the men to work on their behalf. He was not just tasked with delivering their messages to the officers, he was charged with vigorously defending these interests. It should not be entirely surprising that pirates selected someone who served as a 'lowly' petty officer in legal voyages to serve such an important duty; he was closer to the regular before-mast sailor than most other officers and would (hopefully) have been keenly aware of their needs and desires.

The other duties of a pirate quartermaster were quite extensive. They can be broadly divided into six areas, the first of which was to represent the crew. The other five include the administration of justice on the ship, recruiting and keeping men, overseeing captured ship boarding, division of spoils, and managing food collection and distribution. Each will be examined in some detail with regard to the Golden Age of Piracy (GAoP). Before discussing pirate quartermasters, the role of later-period buccaneer quartermasters, an officer which both predated and prefigured the pirate quartermaster, are considered.

Officers In Charge of Food - Buccaneer Quartermasters

In his account of the voyage of buccaneer Jan Willem's vessel Princess in the mid-1680s, William Dampier declared that the role of Quartermaster was "the second place in the Ship, according to the Law of Privateers"1.

Artist: Thomas Murray

William Dampier (c. 1697-8)

If the Law of the Privateers (aka. Buccaneers) was ever written down, there doesn't appear to be any record of it. However, this provides an early example of the quartermaster's greatly elevated position among a ship's crew.

The quartermaster was involved in making decisions about a ship's sailing and other affairs on buccaneer vessels, just as he was on navy and merchant vessels. When buccaneer captain Edward Cooke's ship Virgin was foundering in a storm in 1683 and the sailing master threatened to cut the masts down, the more experienced quartermaster Edward Davis "bid him hold his hand [from chopping down the masts] a little, in hopes to bring her some other way to her course", which they eventually did.2 Forced buccaneer surgeon Hermann Coppenger attempted to escape from the Cygnet in a Canoe at the Nicobar Islands in 1688, but Quartermaster John Oliver "leapt into the Canoa, taking hold of him, took away the Gun, and with the help of two or three more, they dragged him again into the Ship."3 This shares some similarities to the golden age pirate quartermasters who were typically in charge of recruiting and keeping men aboard once they joined the crew.

There is little to indicate that the buccaneers quartermaster oversaw the administration of justice on a ship. This isn't to say it didn't happen, only that none of the contemporary authors saw fit to mention it. In his account of the buccaneer voyage of Captains Coxon, Sawkins, Sharp and others,

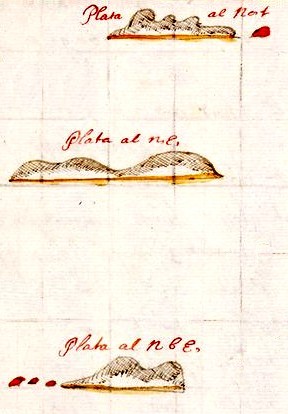

Cartographer: Basil Ringrose

Ringrose's Views of Isla de la Plata (1682)

Basil Ringrose notes that when they reached the Isle of Plate (Isla de la Plata, Ecuador) in August of 1681, "our quarter-master, James Chappel, and myself, fought a duel on shore"4. As we shall see in the information on pirate quartermasters, this was how some disagreements between the pirate crew men were settled, being ordered and overseen by the quartermaster. However, Ringrose provides no information on what caused his disagreement with the quartermaster, how it was decided that a duel should be fought to settle it or even what occurred as a result.

Similarly, no mention is found in the buccaneer tomes of a quartermaster overseeing the distribution of captured wealth. Once again, Ringrose's text broaches the subject without defining what role, if any, his crew's quartermaster had in dividing the spoils. The buccaneer crews were near Barbados in January, 1682 when they divided the spoils of the last prizes taken. Ringrose notes that a 'little Spanish shock-dog' was auctioned off, which the Captain Sharp bought to eat in case they didn't reach land quickly. The proceeds of that auction "with one hundred pieces of eight more, which our boatswain, carpenter, and quarter-master had refused to take at this last dividend, for some quarrel they had against the sharers thereof, was all laid up in store till we came to land in order to be spent on shore, at a common feast, or drinking bout."5 This is tantalizingly close to linking the quartermaster to the division of spoils, however all it says is that he and some others refused part of the money from the division which had taken place previously.

Speaking of dogs,

Apparently, You Do Not Want to Be a Buccaneer's Dog.

From On the Spanish Main, By John Masefield (1906)

food and quartermasters, Ringrose notes that for Christmas of 1681, Captains John Cox of the May-flower and Bartholomew Sharp of the Trinity, "had a little sucking Pigg in one of them, which we kept on Board ever since for our Christmas days Dinner which now was grown to be a large Hogg... but thinking it not enough for us all, we bought a Spaniel-Dogg of the Quarter-Master for forty pieces of Eight, and killed him; so with the Hogg and the Dogg, we made a Feast"6. Once again, however, Ringrose fails to tie the quartermaster to victualling in any direct way.

Fortunately, there are other examples. French Buccaneer Raveneau du Lussain links food with the quartermaster during a description of another Buccaneers' Christmas meal in 1687. It come from a comment made in passing, which states that "one of our quarter-masters, [had] gone ashore, in order to take care about our eating some victuals, (for our ships being a careening, all our provisions were then put out,)"7. This directly suggests the quartermaster was responsible from bringing the food to the buccaneers for preparation. I n July of the same year, Dampier says that the quartermaster of the Cygnet went ashore at Pescadores (Penghu) Islands Island in the Philippines to meet with the governor who "very kindly told our Quarter-master, that whatsoever we wanted, if that place could furnish us, we should have it."8 The governor was cautious, explaining that he would send men out the Cygnet with food rather than allow the men to come ashore to get it.

A Wholly Inaccurate Image of Edward Davis, From Lambert and Butler Cigarette Cards (1926)

Another point of interest was the tendency of buccaneers to promote their quartermaster to the role of captain when the situation warranted, something pirates also did. In 1683, Dampier talks about "one Mr. Cook, an English Native of St. Christophers, a Cirole [Creole], as we call [them], all [being] born of European Parents in the West-Indies."9 Captain Jan Willems had captured a Spanish prize which they decided to keep, so "Mr. Cook being Quarter-master under Captain Yanky [Willems], the second place in the Ship, according to the Law of Privateers, laid claim to a Ship they took from the Spaniards."10 This appears to have been Edward or Edmund Cooke. Furthermore, when Cooke died in July of 1684, Dampier says that "Mr. Edward Davis, the Company's Quarter-Master, was made Captain by consent of all the Company; for it was his place by Succession."11

It is also worth noting that at least one buccaneer ship - John Watling's Trinity - had two quartermasters.12 It seems to have been more usual to have one on a buccaneer ship rather than the four or more found on 'legitimate' vessels. This was probably because the quartermaster's role was less of a leader of the quarter watch and more of an officer in charge on 'illegitimate' voyages. Having several of them would have confused the ship's hierarchy.

1 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 68; 2 Dampier, A Supplement of the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 64; 3 Dampier, New Voyage, p. 483; 4 Basil Ringrose, "A South Sea Waggoner" The Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 289; 5 Ringrose, Buccaneers of America, p. 312; 6 Basil Ringrose, The Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp, And Others, in the South Sea, 1684, p. 108-9; 7 Ravaneu de Lussan, (Taken From A journal of a voyage made into the South Sea, by the bucaniers or freebooters of America, from the year 1684 to 1689), cited in The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 397; 8 Dampier, New Voyage, p. 418; 9,10 Dampier, New Voyage, p. 68; 11 Dampier, New Voyage, p. 118; 12 Ringrose, Buccaneers of America, p. 261