Organizing Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Next>>

Organization of Ship's Food In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 17

Officers In Charge of Food - Cooks

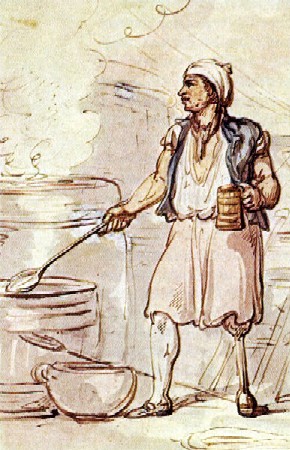

Artist: Thomas Rowlandson - A Post-Period Ship's Cook (1799)

"The seventh [person found on a ship] is the Cook, a most necessary member as long as there will be bellies." (William Welwood, An abridgement of all sea-lawes, 1613, p. 21)

Cooks were an important part of any sailing ship that was at sea for more than a day at a time during the golden age of piracy, so much so that they were sometimes the only officer concerned with victualling on small, privately-owned vessels.1 Unlike other naval officers involved with food on the ship (other than the stewards and their mates), the cooks was fairly low in status, "quite often on a level with the able seamen, paid at their rate for a task which, if it was a specialized one, was not to be regarded as a skilled craft."2 Yet, as Welwood suggests, cooks are found in every type of vessel from navy to pirate and, if not evident on every ship, certainly on most of them.

This section looks first at the role of the cook on a ship including his duties, rate of pay. It then gives a brief history of how the navy chose cooks for their ships, what sorts of skills the men chosen had, information about the cook's assistants and some examples of recorded period problems with cooks. This is followed by a discussion of the cooks other than those who served the before-mast men in naval vessels. This includes cooks for naval officers, merchants, privateers and pirates. Finally, the cook's quarters and the various aspects of the cook room location on naval vessels are examined.

1 Ed Fox, Piratical Schemes and Contracts, 2013, p. 103; 2 Ralph Davis, The Rise of the English Shipping Industry in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, 1962, p. 112

The Role of a Navy Ship's Cook

While each type of ship mentions cooks, a great deal of the information on them and their duties comes from English Navy vessels. Like the naval purser and surgeon, navy cooks were warrant officers, meaning they are, "by the Authority they have received from the Lord High-Admiral, appointed by their own peculiar Warrants."1 Warrants were legal documents given by the navy board to technical specialists.

Sieur Gullet's pithy dictionary defines the ship's cook simply as someone "whose Business is, to Dress, and Deliver out the Victuals."2 When he was the only man directly concerned with the food, as might be the case on more lightly-manned vessels such as many small merchants, the cook might also have to deal with the procurement, selection and storage of victuals. Nathaniel Boteler wrote that in the early half of the 17th century, "The Cooks Office is at Sea (as on

Cook in the Cook-Room on a 3rd Rate

From Cyclopedia, Vol 2, Ephraim

Chambers (1728)

the shore) to dress and accommodate all sorts of Victual in the Cook-room according to the number of Messes, and every Mess of men that are aboard the Ship, and this Victual he is to take by tale [total] and weight from the Steward and Purser, and being Cooked, to deliver it" to the sailors representatives.3 A 'mess' was a group of 4 to 6 sailors who agreed to eat together as a regular group. One man was chosen from each mess to serve as the 'cook' for that mess. It was his job to get the food which needed from the steward, deliver the things which were to be boiled to the cook and retrieve it once ready for delivery to his mess. Boteler's book being focused on the navy's concerns, he adds, "it behoves him [the cook] to observe [the men coming to get their food from him] needfully, lest otherwise both himself and some other Messes be cousened [cozened - tricked out of] of their dues, by delivering twice to one Mess"4.

Writing not long after Boteler, William Monson said that the cook was

Artist: Thomas Rowlandson - Ship's Cook Sketch

to dress and deliver out the victuals and is assisted by a mate or two; the meat being sodden, either of fish or flesh, he delivers it forth to them appointed to mess the company, and after to put out the fire and suffer none to be kindled, or people to resort into the cook-room but in case of necessity; as namely, when the cockswain's gang comes wet aboard, or sick men have occasion to use the fire for their comfort.5

Monson's experience was from his time serving in the navy in the 1620s. His detailed information specifically notes the importance of the cook's duty to care for the cooking fire, making sure it didn't get out of control, which was not to be taken likely in the wooden, tar and canvas world of an 18th century ship. The cook would arise early every morning to light the fire in preparation for breakfast and put it out after dinner every night to reduce the danger it might pose by its unguarded overnight presence in the wooden world.

Ned Ward provides a sharp, rather cynical view of the ship's cook and his duties in his satirical book from the period:

Tho'' salt Water's the Element that supports him, yet he can no more live without Fire, than a Salamander... he [spends] every Day in burning, boiling, and broiling. …He sucks in Smoak, like a Virginia-[Tobacco ]Planter, and is every Morning hanging his Head over the unctuous Steams of the Caldron… In fine, he's so everlastingly encompass'd with Smoak, and his Face so cak'd over with Soot.6

We shall see in a following section that the cookroom was located below deck and, although chimneys were built to funnel the smoke out, it must have been a rather hot, smoke- and ash-filled room as Ward suggests. Unlike the other (earlier period) authors, Ward notably includes broiling (not to mention burning)

Artist: Jost Amman

What a Steeping Tub Might Look Like, From Dast Standebuch (1586)

meat in the cook's duties. Yet, as he mentioned elsewhere, Ward said that all of the cook's skills were encompassed by the sea kettle - a giant copper pot used to boil food.

In 1731, the navy gathered a variety of orders issued during the previous fifty years and published them as the first published set of navy instructions. This edition of the instructions contained three articles related to the cook's duties. A primary focus of the first two articles was to make sure the meat was 'duly watered' in a steep tub (to remove as much as the salt as possible). The first article also warned that the cooks should keep careful track of the meat so that no "Part thereof shall be lost through his Want of Care."7 The second article notes, almost as an afterthought, that "Provisions [are to be] carefully and cleanly boiled, and issued to the Men, according to the Practice of the Navy."8 No mention of broiling is made, nor are the details of the navy's 'Practice' when it came to cooking spelled out. The third article concerns the care of the steeping tub during a storm and the administrative procedure used when any part of the meat is lost. Clearly, the navy's focus was more on their property, its conservation and administrative procedures related to this than it was on cooking.

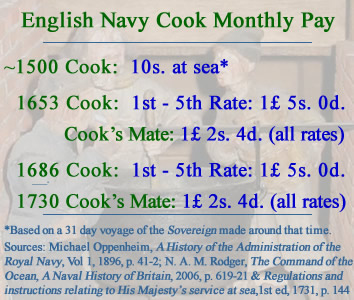

Some of the rates of pay of navy cooks between about 1500 and 1730 are found in the chart at right. Except for the outlier 16th century pay rate, the cook's pay remained constant from 1653 to 1731

English Navy Cook Pay, Photo: Peter Isotalo - Vasa model galley,

(and beyond, actually) while the cook's mate got a slight bump in 1686. Even with this low pay rate, the cook's positions was purchased in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The position clearly lent itself to methods for making it worth the initial bribe required to obtain it. Historian Michael Oppenheim points out that "the cooks had the victuals in their care and recouped themselves at the expense of the seamen"9, most likely by feeding the men less than the navy had allotted to them and returning the unused food for credit or selling it. Like the pursers caught cheating the system in the early seventeenth century, the 1608/9 inquiry into the purchase of naval positions caught the cooks as well. Oppenheim says, "Pursers paid from £10 to £120 for their posts, boatswains £20, and cooks £30."10 This suggests cook's position must have been a good one for graft, particularly considering the low pay. As late as 1632, "one Phineas Eddy paid Portsmouth's Clerk of the Cheque £42 in cash, and gave him a carpet and cushions worth a further £6, in the hope of becoming cook of the Triumph [a second rate ship]"11.

One of the perks of being a ship's cook from well before the golden age of piracy was the fat obtained from cooking meat.12

Artist: Jacob Knyff - HMS Triumph near Dover (c. 1671-2)

Historian Janet MacDonald explains that this was "the meat fat which rose to the top of the coppers during cooking, and which had to be periodically skimmed off. .... When it has cooled and set, [the resulting] slush is little different to suet or dripping."13 The cook could sell this, "theoretically to the tallow merchants on shore but no doubt also to his shipmates. As well as being useful for waterproofing boots, it could be used for frying fish, onions... Beef slush

would be in demand for making puddings."14 Andrew Thrush notes that "even in a ship smaller than the Triumph, a cook at sea for eight months could extract tallow from meat worth between £20 and £25"15.

It is not entirely clear when the practice of buying the cook's position on a navy vessel began. Writing around the late 1630s/early 1640s, Nathaniel Boteler wryly commented, "I doubt not but these Cooks know well enough how to lick their own fingers; and I assure my self that their Fat Fees make them savers, whosoever else, loseth by the Voyage."16 Note that Boteler was writing about his own Navy service which ended in 1627. Historian Michael Oppenheim notes, "From about Monson's period [his last service being in the mid-1630s] the custom began of providing maimed veterans, minus an arm or a leg, with cooks' places as a kind of charitable maintenance."17 With the advent of this policy, the ability to purchase a ship's cook position was almost certainly eliminated.

Potential Cooks? Two Greenwich Pensioners Sitting

in the Garden of a Tavern (1791)

Whenever the navy started employing maimed seamen to serve as cooks, it eventually led to some issues. Writing in 1671, clerk John Baltharpe of the HMS St. David said, "Our one Eye'd Cook, is nam'd George Drake, No more of him I do mean to speak."18 This hints at some lack in the cook's ability although nothing is specifically stated in his very tongue-in-cheek poem about the 1669-71 voyage. In 1674, John Gamble petitioned to be assigned as cook to HMS Sweepstakes because he had lost "both his arms in fight the 11th of August 1673"19. Astonishingly, the navy found no reason not to assign a man with no arms to be a cook and requested that he be given a berth as soon as possible.

The navy eventually realized it had to address such issues. A petition was received about two years after Gamble's by some employed, wounded cooks requesting the 'allowance of a servant'. The navy agreed, writing, "That to such of them as by losing both arms or both legs shall be wholly disabled to help themselves without the assistance of another, a servant shall be allowed to be borne above the complement of the ship."20 From this, it is clear that the navy's choice of ship's cook was a charitable gesture having nothing to do with a man's cooking skills.

The cooks' assistants/servants (typically referred to by the navy as 'cook's mates') might have been employed for their cooking skills, although this also seems unlikely. So little concern seems to have been given to their food preparation skills that in 1694, Captain George St. Lo suggested "sturdy

Photo: Peter Isotalo

A Cook's Mate, Vasa Model, Vasa Museum

beggars, vagrant persons, deer-stealers, such as [those who] rob fish-ponds, coney-warrens, dove-houses, or the like... will make cook's-mates, shifters and swabbers, &c. which must be had on board as well as other men; and doubtless many of them, when they are broke from their loitering and idle courses and see themselves confined on board, may take up and make good sailors"21. Fortunately for the quality of the food, his suggestion doesn't appear to have been acted upon by the navy.

In addition to cook's mates, Captain St. Lo mentions shifters in his proposal. These were "those Men on board a Man of War, who are Employ'd by the Cooks, to Shift or Change the Water in which the Fish or Flesh is put and laid for some time, in order to fit it [remove the salt] for the [boiling] Kettle."22 As early as the mid-seventeenth century, there was concern about the effect of salt on the health of the men. As Nathaniel Boteler explained, the cook was "to take especial care, that both the Flesh and Fish be timely and sufficiently watered and shifted, for the holsome feeding of the Ships Company"23. He notes that he doesn't consider shifters to be officers, he instead calls them assistants to the cook. Shifters probably had additional duties; the pseudonymous Barnaby Slush notes that sons of important men should expect "to preside over the Shifters, and to see the Coppers thorowly well Scour'd, for the Benefit and Health of the Ships Company."24

A degree of conscription may have been involved in filling the disabled cook's position. In 1700, the Navy Board, responded to requests for relief from some of the wounded sailors turned cook with the order: "We do hereby desire and direct you to give the necessary orders, that all such cooks, of the third rate and upwards, who have lost their eyes, both their legs, or both their arms, be excused from doing their duty on board ship, without being put to the charge of deputies [their assistants/servants]."25 Yet in 1704, the muster master of the fleet wrote the Board to complain that aboard the 3rd rate Content, "The cook is stone blind and utterly incapable of all services to her Majesty, her officers, and

Artist: Isaac Cruikshank - Greenwich Pensioners (1791)

those ordered to be borne in the hulk."26 Writing in 1708, Ned Ward sarcastically commented that a ship's cook was someone who "HAS been an able Fellow in the last War, and had been so in this too, but for a scurvy Bullet at La Hogue, that shot away one of his Limbs, and so cut him out for a Sea-Cook. But how disabl'd soever he be himself, his Mate is a rare Stick of Wood for a Furnace."27

While reserving the cook's role for wounded sailors hints at compassion on the English navy's part, it also suggested that food preparation didn't require any skill as mentioned. Naval historian J. D. Davies points out, "Unsurprisingly, few, if any, naval cooks had genuine culinary ability, but the relatively limited nature of the naval diet meant that he did not have to master a particularly extensive menu. Arguably, the more important role was to ensure that each man, and each mess, got a fair share and no more."28 Janet MacDonald says, "With rare exceptions, any actual cooking skills would be minimal and learned along the way. There was certainly no training in the culinary arts for these ships' cooks."29 Near-period author Ned Ward explained, "He cooks by the Hour Glass… All his Science is contain'd within the Cover of a Sea-Kettle. The composing of a Minc'd-Pye, is Metaphysicks to him; and the roasting of a Pig, as puzzling as the squaring of a Circle."30 Ward also claims that the cook's "Knowledge extends not to half a dozen Dishes"31. Given that there were about half dozen things to be cooked during a voyage such as fish, salt meats, peas, oatmeal, rice and puddings, this doesn't say much for the man's skill.

There are a couple of examples of cooks misbehaving once the policy of employing wounded men was instituted. Some concern the cook being intoxicated, something not an entirely uncommon amongst sailors at this time. Meredith Price of the HMS Nightingale was removed from office in 1654, "being 'much given to drink, swearing and railing, and his unhandsome ordering of meat has much disturbed and prejudiced the

Copper Pot with Verdigris Formation

ship'."32 One cannot but help wonder at the meaning of "unhandsome ordering of meat". In 1694, Edward Barlow reported that William Cox, the cook aboard the merchant Sampson, upon awakening during "the night rises out of his sleep and goes into the ship's head and either slips or falls overboard and was 'drownded': he was drunk, and was not missed till the next day at nine in the morning"33.

Sometimes the cook's skill was cause for punishment. In 1698, cook Edward Ham of the merchant vessel Adventure was punished "upon a complaint of the copperishness of the Pease, the Captain himself went into the Cook-room, and took off the sides of the Copper [pot] a great quantity of Verdigreese, for which the Captain beat him with a Japan Cane, but not to that degree as at all to wound or break his Skin"34. In 1708, Captain Hodsell of HMS Squirrel reported trouble with his cook because Hodsell asked for purchase some pork fat (slush) to finish tallowing the bottom of the ship. The cook refused, threatening legal action if the captain attempted to take it. After this, the cook continued to misbehave, trying to get the sailors to mutiny. "[The cook] was a very young fellow, and neither seaman nor pensioner. And when I confined him, he broke out, and threw the irons overboard, and several times sent to tell me I was a rogue, and that the Devil would fetch me away, and that he cared not a pin for me, for his warrant was as good as my commission."35 So the captain left him on shore. As a result, the navy ordered the man not be employed again as a cook and asked the Navy Board to explain why they had appointed a young man who was not wounded in the first place.

1 Josiah Burchett, "Preface", A Complete History of Transactions at Sea, 1720, non paginated; 2 Sieur Guillet, The Gentleman's Dictionary, 1705, not paginated; 3 Nathaniel Boteler, Colloquia maritima or Sea Dialogues, 1688, p. 22-3; 4 Boteler,p. 22-3; 5 William Monson, The Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson, Vol. IV, M. Oppenheim, ed., 1913, p. 52; 6 Ned Ward, The Wooden World Dissected, 3rd ed, 1744, p. 60-1; 7,8 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea,1st ed, 1731, p. 135; 9 Michael Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, 1896, p. 146; 10 Oppenheim, p. 194; 11 Andrew David Thrush, "The Navy Under Charles I," Doctoral Thesis, 1990, p. 164; 12 Footnote, R. D. Merriman, Queen Annes Navy, 1961, p. 195; 13,14 Janet MacDonald, Feeding Nelsons Navy, 2014, p. 104; 15 Thrush, p. 164; 16 Nathaniel Boteler, Colloquia maritima or Sea Dialogues, 1688, p. 22; 17 Footnote, William Monsons Naval Tracts, Vol IV, Michael Oppenheim, ed., 1913, p. 61; 18 John Baltharpe , The Straights Voyage, or, St. Davids Poem, 1671, p. 11; 19 "December 23, 1674, Admiralty Journal", Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, Vol IV, J. R. Tanner ed, 1903, p. 118; 20 "September 16, 1676, Admiralty Journal", Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, Vol IV, J. R. Tanner ed, 1903, p. 351; 21 "3. Captain George St. Lo, England's Interest; Or, A Discipline For Seamen (1694)", The Manning of the Royal Navy, Selected Public Pamphlets, J. S. Bromley Ed., 1974, p. 35; 22 Sieur Guillet, The Gentleman's Dictionary, 1705, not paginated; 23 Boteler, p. 23; 24 Barnaby Slush, The Navy Royal, Or a Sea Cook Turn_d Projector, 1709, p. 9; 25 "Admiralty to Navy Board, August 6, 1700", The Sergison Papers, (Naval Clerk of Acts), R. D. Merriman, ed., 1950, p. 206; 26 Queen Anne's Navy, Merriman, ed., p. 188; 27 Ward,p. 59; 28 J. D. Davies, Pepys's Navy, 2008, p. 102; 29 MacDonald, p. 104-5; 30,31 Ward, p. 59; 32 N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, A Naval History of Britain, 2006. p. 60; 33 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of His Life at Sea In Kings Ships 1559-1703, 1934, p. 445-6; 34 “49. Mutiny on the Ship Adventure”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 256; 35 "Captain Hadsell, Squirrel, to Secretary of the Admiralty, Leith Roads, 13th August 1708", Queen Annes Navy, p. 195

Examples of Cooks Other Than a Regular Navy Ship's Cooks

Because navy records provide the most information about the role of a ship's regular cook, the previous section focused on them in some detail. However, cooks were probably the most ubiquitous ship's officer concerned with food, being found on nearly every ship that sailed during the golden age of piracy. Let's look at some of the cooks other than those who served the before-mast men on navy vessels.

There was often a captain's or officer's cook on navy ships, hired and paid by the officers. He was recruited by the officers because he was better qualified than the man assigned to the before-mast men. Ned Ward commented,

Artist: Gabriel Bray - Later Period Officers Drinking Tea (1775)

"The Captain's Cook and [the regular cook], are Opposites, as well in their Practice, as in their Habitations, and seldom or never make Incursions into each other's Provinces."1 Historian J. D. Davies explains that navy captains in the late 17th century, "often brought aboard their own provisions, had their meals cooked separately and frequently laid on meals for their own or visiting officers that resembled grand banquets ashore."2 Speaking about a later period, Janet MacDonald explains that the officers might employ "a professional cook, engaged to perform his art, [who] would arrive on the ship with his own 'batterie de cuisine', the pots and pans and everything else he felt he needed."3 Her allusion to the French is significant.

While ship's chaplain Henry Teonge didn't mention the officer's cook specifically, he spent a great deal of time describing the officer's food aboard both HMS Assistance (1675-6) and Bristol (1678). For example in November of 1678, "We had an aitchbone [rump] of good beef and cabbage; a hinder-quarter of mutton and turnips; a hog’s head and haslett [pig’s chitterlings or intestines] roasted; three tarts, three plates of apples, two sorts of excellent cheese: this is our short-commons at sea."4 For such meals, the pseudonymous 'cook' Barnaby Slush notes that live animals were kept on board navy ships, including "many Hogs, Dogs, Sheep, Goats, Geese, Turkys, Ducks, Hens and so on, belonging to the Officers"5, noting that he is not considered an officer.

The East India Company (EIC), being the largest sort of merchant vessel, also had the fullest complement of food-oriented officers, similar to the navy. When they were building and manning their own vessels,

Artist: Peter Monomy - An English East Indiaman (c. 1720)

the EIC's rules mentioned the cook, although they had little to do with his primary function. Not surprisingly, the EIC's rules regarding the cook were very similar to those of the English navy than the average merchant vessel. The EIC's 1621 rules, lump the cook in with several other officers of the ship including the Boatswain, Gunner, Steward(s), Cooper, Carpenter and Armorer. In a sweeping statement, the rules said that these officers were to "take charge of all the Provisions, Victuals and Stores [relevant to their position] for the Voyage, which shalbe assigned unto them severally to use, and to give Accompt of the same to the Purcers or their Mates, it all times when it shall be required."6 Like the navy, this early description of the cook's role says nothing whatsoever about actually cooking, focusing instead on accounting for the food. They also said that the cook's implements were to be accounted for using written receipts given to the purser, with the cook "accomptable for the same, and the said Receipts shall be orderly testified by the Master of the Ship, or some other knowne men"7. The use of accounting with regard to food and cooking tools were clearly to prevent theft. EIC cooks also had assistants or mates to help them similar to the navy according to a 1703 deposition by Thomas Parr concerning the wreck of an East Indiaman in Bengal.8 Finally, EIC vessels sometimes had a captain's cook like large naval vessels as well as a butcher, baker and poulterer.9

Being free from both navy requirements and emulation, merchant ships could have chosen men better qualified for the task. However, merchant ships were often minimally crewed to make the cost of transporting goods as affordable as possible. Historian Peter Earle says that the crews of small merchant vessels "would have a master, mate, carpenter, cook, boy and four or five foremastmen"10. Here, the cook's duties might include purchasing foods when necessary, retrieving the food from storage, serving it to the sailors and gathering the remains in addition to cooking. Earle elsewhere explains that on merchant vessels, the cook and carpenter did not typically have to keep watch on the ship, although he adds that if the crew were small enough, they might still end up with this job as well.11

Unfortunately, little is said about a merchant ship's cook's duties in the period and near-period sailor's accounts. Information on merchant ship cooks is mostly limited to a mention in the records that they were aboard. In the 1650s, Edward Coxere was sailing on a Dutch vessel to the Mediterranean. He noted that although the cook was the only crew member to have been there before, he was "of no value except to boil the kettle, for which he was very expert."12 This should not be entirely surprising given that the cook arose early to start the cooking fire below deck and then had to tend it until putting it out after dinner. Yet there are echoes of the regular navy cook in Coxere's description. In May of 1694, merchant Captain Thomas Phillips of the slaver Hannibal noted they when they reached Whydah, Africa, they took "our [ship's] cook ashore and eat as well as we could, provisions being plenty and cheap"13.

Francis Rogers reported that the cook on the merchant vessel Arabia

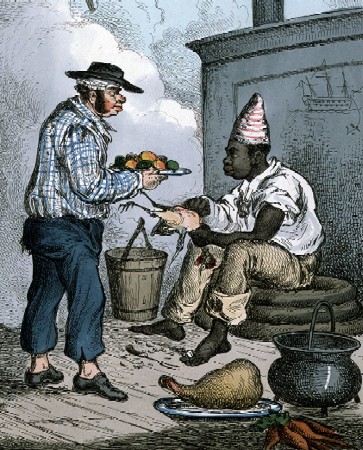

Artist: Thomas Maclean - Later Period Cook's Mates Preparing Food (1831)

died of an illness on June 23rd, 1702. He was buried at sea, being sewn into his blanket and 'heaved' overboard the next day. Rogers reported that on the 25th, "10 or 12 sharks hankered about the ship for such another meal, they having met with the poor greasy cook."14 This description is similar to that given of the cook taken by Edward Low's men out of a French merchant vessel in July, 1722. Captain Johnson reported, "They took all the Crew out of her, but the Cook, who, they said, being a greazy Fellow, would fry well in the Fire; so the poor Man was bound to the Main-Mast, and burnt in the Ship"15 . While it is not entirely clear what 'greasy' means in these texts, the cook worked in the hot confines of a ship's cookroom all day, so it likely refers to how sweaty the man was.

Returning to Francis Rogers' account, he mentions that in August, the Arabia reached Aden in what is today Somalia. There, the captain, Rogers, the second mate and "our Negro cook" went ashore to meet the governor and make arrangements to get supplies.16 This is not the only instance of an African merchant ship's cook (or at least a cook's mate referred to as a cook) from this period. In Thomas Bowrey's 1704 records for the merchant ship Mary, it says that the crew "consisted of… John Painter; a cook… [and] Nicolo, a cook, and a boy, both of whom were Black slaves."17 Here, it is likely that the slave was the cook's assistant or mate. However, the cook on Rogers' ship had died the month before they reached Aden so it is likely their African American cook's mate was promoted to be the cook.

Privateers would necessarily have needed a cook because they often sailed for long periods against enemy ships and enemy waters. There are just a few privateer accounts under study here and only one mentions cooks, that of Woodes Rogers voyage around the world from 1708-11. Even this doesn't give much information; the cooks simply appear in his list of officers on the voyage. They include "William Hopkins,

Taking A Turtle on Shore, From The West Indian Atlas, By Thomas Jefferys (1783)

Ship's Corporal, Capt. Dover's Serjeant, and Cook to the Officers; Barth. Burnes, Ship's Cook" both aboard the Duke.18 It is interesting that they had an officer's cook like the navy and East India ships.

This brings us to the buccaneers who sailed in the period just before the golden age of piracy. It is commonly noted that the word 'buccaneer' is derived from the Arawak word for the platform made of sticks used to smoke meat. While this link between buccaneers and barbecuing is fascinating, little is found in the period sea accounts about the buccaneer cooks themselves. William Dampier, mentions that the buccaneers he sailed with in 1684 "sent ashoar the Cook every morning [while in the Galapagos Islands], who killed as many [turtles] as served for the day. This custom we observed all the time we lay here, feeding sometimes on Land-Turtle, sometimes on Sea-Turtle, there being plenty of either sort."19

Several ship's cooks are found in pirate accounts from the period. Captive Richard Hawkins said of Francis Spriggs pirates, "at Meals the Quarter-Master overlooks the Cook, to see the Provisions equally distributed to each Mess"20, indicating the hierarchy found among pirates, at least in that crew. Jacob du Bucquoy, captive of John (Richard) Taylor, found those pirates had "a great appetite, for hunger is their chief cook; generally they suffer from lack of food."21 It is not clear that Taylor's crew had a cook at all at that point, for du Bucquoy later says that they put him in charge of cooking.22

Artist: Isaac Sailmaker

Ships at Bridgetown, The Island of Barbados (c. 1694)

It is curious that they thought fit to put a prisoner and forced man in charge of the food. This practice is not unique to Taylor. Hawkins said that the cook on Spriggs' ship was a prisoner and "a Negroe Free-Man"23. George Condick, cook aboard William Fly's pirate ship, was described as "a young man of twenty years, had usually been the worse for drink and not able to bear arms when vessels had been taken."24 The only other pirate cook mentioned is Thomas Johnson, who was aboard Henry Every's Fancy.25 Nothing more is known of him in this capacity.

It is interesting that three of the cooks identified were either prisoners or not qualified to be marauders. This suggests that, at least in these cases, the pirates looked upon the cook in a manner somewhat similar to that of the navy: a job to be filled by anyone available who wasn't going to be useful elsewhere on the ship. The fact that the cook's job involved regular, tedious work in a hot and smelly environment may have resulted in such choices as well.

One of the men who became a pirate captain was a former cook according to Charles Johnson. He explains that Nathaniel North became a sailor when he was "the Age of 17 or 18, shipping himself Cook on board a Sloop, built at Bermudas, for some Gentlemen of Barbadoes, with Design to fit her out for a Privateer." (So at least one other privateer ship is mentioned as having a cook.) According to Johnson, North's father was a sawyer (literally, a wood 'sawer'), an occupation in which North had been trained before turning ship's cook. Once again, we find a thoroughly unqualified (not to mention young) man taking on the role of cook on a ship, which suggests that a ship's regular cook's skills had little to do with his being selected for the job.

1 Ned Ward, The Wooden World Dissected, 3rd ed, 1744, p. 59; 2 J. D. Davies, Pepys's Navy, 2008, p. 153; 3 Janet MacDonald, Feeding Nelsons Navy, 2014, p. 132; 5 Henry Teonge, The diary of Henry Teonge, 1825, p. 228; 5 Barnaby Slush, The Navy Royal, Or a Sea Cook Turn'd Projector, 1709, p. 71; 6 East India Company, The lawes or standing orders, 1621, p. 49; 7 East India Company,p. 47; 8 Peter Earle, Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775, 1998, p. 50; 9 Cyril Northcoat Parkinson, The Trade Winds, 1948, p. 148; 10 Peter Earle, Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775, 1998, p. 42; 11 Earle, p. 71; 12 Edward Coxere, Adventures by Sea of Edward Coxere, 1946, p. 18; 13 Thomas Phillips, "A Journal of a Voyage Made in the Hannibal," A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol VI, Awnsham Churchill ed, 1732, p. 218; 14 Francis Rogers, "The Journal of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, Bruce Ingram, ed., 1936, p. 163; 15 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, 1999, p. 323; 16 Rogers, p. 172; 17 Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey 1669-1713, 1927, p. 177; 18 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 7; 19 "59. Richard Hawkins’ account of his capture by Francis Spriggs," The British Journal, 8 August, 1724 and 22 August, 1724", Pirates In Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 301; 20 Jacob du Bucquoy, Jacob de Bucquoy Hydrographer and Cartographer of the Netherlands, Baylus Brooks, interpreter, 2018, p. 27; 22 Bucquoy, p. 32; 23 "59. Richard Hawkins’ account...", p. 299; 24 George Francis Dow and John Henry Edmonds, The Pirates of the New England Coast 1630-1730, 1996, p. 336; 25 Ed Fox, King of the Pirates, 2008, p. 116; 26 Defoe (Johnson), p. 511