Organizing Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Next>>

Organization of Ship's Food In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 7

Officers In Charge of Food - Ship's Pursers

Pursers have existed in the English navy since the 14th century, a century before the 'Navy Royal' was established by King Henry VIII in 1546. In simplest terms, a ship's purser was "the Officer who is entrusted with

Ship's Purser in 1787, From Players Cigarette Cards,

History of Naval Dress Series, No. 13 (1929)

the keeping and distributing the Provisions out to the Ship's Company"1. However, this oversimplifies the purser's responsibilities; he was financially responsible for all of the provisions and many of the consumables brought aboard his ship. "He was a combination of paid employee and entrepreneurial businessman, allowed to sell certain items to the crew."2

Pursers acted as a liaison between the navy and the men on the ship in most matters pertaining to provisioning. Having to limit the men's access to food made them unpopular with the men, who often accused the pursers of cheating them. Unfortunately, the purser's role was structured in a way that made this possible, so there was some truth to the sailor's suspicions

This first part of this section takes a brief look at the history of the naval purser up until the beginning of the golden age of piracy around 1690. The second part examines the pursers' responsibilities to their ship and crew along with their management of the King's money during the golden age of piracy. The bulk of the third part looks at how and why pursers might have cheated the men of their victuals, providing both legitimate and illegitimate examples of the this. It finishes with examples of complaints levelled at pursers in sailor's accounts, both just before the period of interest as well as during it.

1 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea,1st ed, 1731, p. 113; 2 Janet MacDonald, Feeding Nelsons Navy, 2014, p. 91-2

A Brief Look at the Early History of Navy Ship Pursers

In the early part of the fourteenth century, the role that eventually came to be called 'purser' was then called the clerk, bursar or

King Henry VII (1505)

'clerk of the bursar'1. Bursar comes from the Latin word bursarius,2 which refers to a 'purse-bearer'3, so the clerk of the bursar would be defined as the keeper of the purse on a ship. The term 'purser' referring to a ship's officer first appears in print in the accounts of the corporation of Lydd in the southeast of England in 1445. The document says, "Delivered to Richard Hughelot, mariner, pursure of the said ship of the town of Lyde, 6li. 3s. 4d."4 This is in line with the role of a bursar. There are a few similar brief mentions of pursers on ships giving and receiving money during the later half of the 15th century, although there is little else in the way of description of the role during this period.5

During the reign of Henry VII (1485-1509), the purser of the English navy vessel Sovereign was paid 1s. 8d. a week while the ship was in the harbor and 14s. 8d. for a 31 day journey - or about 2s. 8d. per week.6 (By way of comparison, in 1687 a purser's pay depended on the size of the ship (or navy rating) he managed, varying from £4 to £2 5s. per month.7) The navy at this time was still largely temporary, having only two men-of-war and 16 hired merchant vessels as of 1490.8

The role of purser became more important with the establishment of the Navy Royal under Henry VIII. Before 1520, pursers were in charge of purchasing consumables for the ship. They got their money from the treasurer of the fleet and were to make sure the purchased victuals got delivered to the ship. The ship's steward then took care of their stowage and eventual distribution.9 Between 1511 and 1514, money was given to ship's pursers to pay for things like victualling, sailors and officers wages, the rent paid for merchant ships used by the navy, ship's supplies (Including cannon, hemp to make "cabullys, ratlyn and marlyne" for the Henry Grace a Dieu, "streamers and banners (specified) made" for the Gabriel Royal and a "small warpe" sail for the Henry Hampton, as well as to pay for repairs such as "decking and rigging" for the Mary Rose.10

Artist: Anthony Anthony - Henry Grace à Dieu (c. 1546)

The Henry Grace a Dieu was considered large and important enough to rate two pursers.11 Pursers were also supplied with 'necessary money' at the rate of 2d. per month for candles, wood and other consumable items the ship needed.12 This custom was expanded to other items, continuing well beyond the Golden Age of Piracy.

Since they were in charge of these purchases, pursers were held to account provisioning problems at this time. In 1513, navy admiral Edward Howard sailed to attack the gathering French fleet without stopping to reprovision his ships. Howard drowned during an attack which, combined with a shortage of victuals, caused the English fleet to return to Dartmouth claiming they only had three days of victuals left. "It is doubtless in connection with the return of the fleet that officials wrote,' I fear that the pursers will deserve hanging for this matter,' noting that this was 'an outrageous lack on the part of the pursers.'"13

The purser's role in direct purchasing of supplies and victuals began to be reduced in 1525 when William Gonson was given responsibility for victualling navy ships which were not part of a major military enterprise. Gonson appears to have appointed men to purchase supplies on his behalf and deliver them to the appropriate naval vessels. "Such a system must have been both more efficient and less subject to abuse than funding [food purchases] through the pursers"14. The navy still sent money to the pursers through Gonson "in the event of accident or emergency, and also to provide dietary supplements, such as fresh fruit and

Artist: Afredo Roque Gameiro - Carregamento de especiarias em Calicute (1922)

Loading a 15th Century Portuguese Vessel. Shown for 15th c. Loading Since It Has Little to Do With the English Navy

vegetables, which did not come within the scope of the victuallers' activities."15

Victual purchasing became even more centralized with the appointment of Edward Baeshe and Richard Watts as 'surveyors of victuals within the city of London' in 1547. Baeshe was made the sole overseer of the program in 1550.

A sea 'menu' was formalized in 1565 which included beer, four 'flesh' days, three 'fish' days along with bread or biscuit, butter and cheese. Historian David Loades notes that this "carefully stipulated schedule [of victuals] ...certainly went back to 1545, and probably much further."16 The navy declared that "good and seasonable meat and drink shall [be] deliver[ed] to the pursers, that is to say when the ships" lay in English ports near Baeshe or his agents.17 "Before 1550 the purser's discretion, as well as the officers' private means, had meant that a variety of other foodstuffs, including fruit and poultry, were often present on board, although it is difficult to say in what quantities. After 1550 this became more difficult, but pursers did still claim and receive sums of money for supplementary victualling, which was probably of this nature."18

Historian Michael Oppenheim says that when Sir John Hawkyns became Treasurer of the Navy in 1578,

John Hawkins, National Maritime Museum (1581)

he "made a clean sweep of many naval abuses of long standing"19, citing a report by Sir Robert Cotton written in 1608 which said that under Hawkyn's "control as a standard during which the business of

the Navy was well and honestly done."20 However, Oppenheim also admits that other observers suggest Hawkyns may have been as corrupt as many others in the Elizabethan hierarchy.21 Still, there is evidence that the abuses ramped up soon after Hawkyns death in 1595. Oppenheim says that "[a]buses unknown during the lifetime of Hawkyns had sprung into existence shortly after his death" in 1595 which allowed "captains, pursers, and victuallers to return false musters, and the practice of selling appointments to minor posts [such as ship's purser] were all, according to reliable evidence begun about 1597 or 1598."22

Navy ship's purser positions were often sold, which hints at how lucrative holding the post could be at this time. A witness testified at an inquiry conducted in 1608-9 "that of late years the general way of preferment is by money and few that he knoweth come freely to their places."23 During the inquiry, Purser Robert Hooker admitted he bought the pursership of HMS Repulse for £130, sold it for the same price and bought the pursership of the Quittance for £100. His profit on the deal came from charging sixpence a day for victualling ten nonexistent men.24 Victuals meant for the sailors could also be sold ashore by the purser to supplement his income. Despite such inquiries into these practices, they continued for decades. "In the late 1620s the going rate for purserships was said to be £140 or £150. As pursers were paid between 23s 4d and 40s a month, this sort of outlay could only be recompensed by theft."25

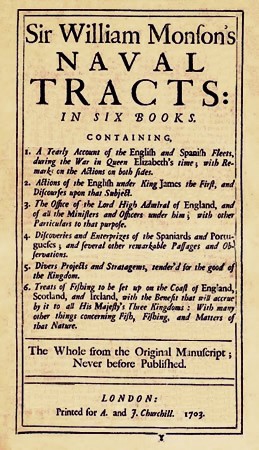

Writing about his service in the navy in the late 16th and early 17th century, William Monson opined,

The gain of the purser at sea far exceeds all other officers, as will appear when their buying their places shall be examined. Both the buyer and seller of this office know that the gain of it must arise by deceiving the King and company. Which, besides that it breeds a great inconvenience, for the purser's unreasonable griping the sailors of their victuals and plucking it, as it were, out of their bellies [by taking less than is paid for and splitting the excess profit with the victualler], it makes them become weak, sick, and feeble, and then follows an infection and inability to do their labour, or else uproars, mutinies, and disorders ensue among the company, that a captain must interpose himself, his reputation, and credit to appease them; and all for the corruption of the buyer and seller of that office. Besides it gives a great discontent to people, and discourages them to do service in the whole voyage.26

'The British Hercules' (1737)

Another potential source of illicit income that began around this time revolved around sailor's pay 'tickets'. Tickets were warrants for pay that were to be reimbursed by the navy treasurer once the ship's voyage concluded. They were given to sailors who left the service before the voyage's end, initially to keep the ship from having to carry large sums of money. However, when the navy ran into serious money troubles in the 1660s, it began using tickets to avoid having to immediately give the sailors actual money.27 This resulted in the men selling their tickets at a discount to people willing to wait for the voyage to end and the navy to pay the sailor's partial salary.28 In addition to merchants and innkeepers, pursers often bought these tickets from discharged men at a discount and even forged them in the name of nonexistent sailors.29

In 1651, the Navy Commissioners looked into fraud in the service and methods for combatting it. Their findings suggested several 'chief' ways that ship's pursers cheated the Royal Navy:

(1) They forge their captains' signatures; (2) make false entries of men; (3) falsify the time men have served; (4) sign receipts for a full delivery of stores and compound with the victualling agents for the portion not received; (5) do not send in their accounts for one voyage till they are again sailing; (6) charge the men with clothes not sold to them; and (7) execute their places by deputy while they stop on shore.30

As a result of the investigation, pursers began to be required to post a bond as security for proper performance of their duties before accepting their position. Stewards were hired to make sure the appropriate amount of victuals were brought to the cook and the pursers were made Clerks of the Cheque - putting them in a position of overseeing purchasing rather than directly handling it, thus limiting their ability to cheat the men. To add further protection against cheating, the captain had to approve all the paperwork written up by the pursers.31 Historian Michael Oppenheim suggests that these methods were effective based on the decrease in the number of trials for embezzlement after 1653.32 However, historian N. A. M. Rodger points out all it did was encourage the pursers/Clerks of the Cheque to work with their captains and stewards to continue to cheat the system.33 If history is any indication, this may have been the case because the purser's role as purchaser was restored in 1655 and their 'cheque' role was eliminated.

The purser's role evolved in the 17th century. In 1623, a supply of clothing was ordered to be made available for purchase by the sailors aboard ship "to avoyde nastie beastlyness by contynuall wearinge of one suite of clothes, and therebie boddilie diseases and unwholesome ill smells in every ship."34 The responsibility for purchasing and selling the clothing was the purser's, he earning one shilling per pound of cloth sold. "By 1636 the commissions had increased. The merchant had to pay two shillings in the pound for entering the clothes on board; the paymaster and purser took each a further shilling on all articles sold, and of course the unfortunate sailor had to meet all these extr, illegal perquisites. The result was that 'the men had rather starve than buy them.'"35

Because of the way the English government purchased food and

Artist: Claude Lorain - Port au Soleil Couchant (1639)

paid pursers during this period, the pursers were sometimes required to finance their own food purchases out of pocket at foreign ports. They then had to apply for approval and reimbursement of such expenses. By 1628, new ship's pursers were also required to give port victuallers surety in an effort to prevent fraud and prove they could afford to pay for victuals. In 1630, the estate of naval administrator Allan Appsley owed Miles Troughton -the purser of the Happy Entrance - £231 and John Jackson -the purser of the Adventure - more than £221 for supplies for which they had personally paid. The next year the pursers of the Convertive and Tenth Whelp together spent £600 of their own money revictualling their ship while in Spain. "A purser who lacked the means to pay for additional victuals [abroad] was a positive handicap. The deputy purser of the Maria pinnace was described by his captain in 1627 as 'verie poore,...not able to beare his one [sic] charges, by res[o]n yt the cheife purser doth share booth wages & gaynes, so yt hee must be droven [sic] to sell…sum of our victuall."36

Further insight into the role of a purser in the early 17th century is found in the works of Nathaniel Boteler and William Monson. Boteler served in the navy between 1625 and 162837 and his book was most likely written between 1630 and 1640, being published posthumously as Colloquia maritima or Sea Dialogues in 1685. He said that the purser must "be a man both of integrity and sufficiency" since he was responsible for arranging the ship's victualling, stowing the victuals, and keeping track of the sailors and their service in his book, which was then turned over to the navy officials for payment.38

Monson

Monson's Naval Tracts, Title Page (1704)

had more to say about the role. He was at sea in naval service off and one between 1585 and 1614 and again in 1635. He began writing about the navy between 1635 and 1643 with parts of his writings being published in 1682. The full text was published in 1704 in five volumes which discussed the history of the English navy and provided commentary on conditions at sea during the period of his navy career.

In describing the purser's role, Monson begins like Boteler, noting that they were in charge of victualling the ship "according to the proportion allowed by his Majesty, and to see the same delivered daily by the cook and steward to all men at their meals; and at the end of the voyage to deliver an account of his remains, in the presence of the Officers' clerks, unto the Victualler to whom also he must deliver back such cask and biscuit bags as are not spent in the voyage."39 He notes the pursers' responsibility for keeping track of the sailors adding that this was done "in a sea-book, (as we term it) which he should originally receive from the clerk of the checque of the place where the ship was rigged and made ready, mentioning the places where they were prested [given impress or sign-up money] and the day of their entry, with such denominations of offices as properly belong to them."40 Sailors no longer in the navy for any reason during the voyage were to be kept track of in this book so that they weren't paid after they died, deserted or were dismissed. He also mentions that sailors gave the purser six pence per month out of their salary to "provide necessaries, as wooden dishes, cans [mugs], candles, lanthorns, and candlesticks, for the hold."41 These duties continued to be part of the pursers responsibility during (and after) the golden age of piracy.

When the voyage was completed, Monson explains that the purser was responsible for certifying any 'extraordinary' use of the victuals, as well as any that were "wasted, or lost by unavoidable accidents; without which the King's officers should not give any extraordinary allowance upon their accounts respectively, provided that nothing be allowed upon such certificate but what has been formerly lost, and truly issued for his Majesty's service only."42 This hints at suspicions about purser's cheating the system. Strict rules for the accounting for 'lost' victuals would eventually be implemented during the golden age of piracy to try and prevent this.

The next big change to the role of the pursery occurred with the installation of Samuel Pepys in the new role Navy Clerk of Acts in 1662. In this position, Pepys was tasked with overseeing the those responsible for victualling. Navy Clerk Pepys began working on plans to reduce the cost of the navy to the government.

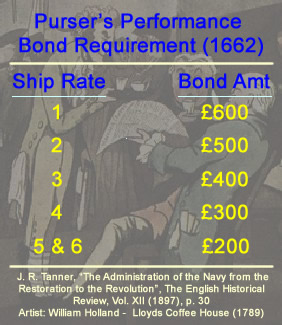

The Duke of York complained about cheating by the pursers, who he said "were negligent and lazy, and took full advantage of their numerous opportunities for peculation."43 To prevent such cheating by pursers, the Navy Board proposed making the practice of pursers providing the navy with

Purser's Performance Bond Requirements in 1662

bonds for security a permanent one in an effort to ensure the "proper performance of their duties" in 1662. Pepys doesn't seem to have been so sure the problem lay with the pursers, however. Writing about a meeting with Tom Wilson and Thomas Hayter in his Diary on November 22nd of 1665, Pepys noted, "Among other things it pleased me to have it demonstrated, that a Purser without professed cheating is a professed loser, twice as much as he gets."44 Often cited as evidence of pursers cheating, he is actually condemning the system in place which encouraged pursers to engage in such behaviors. He felt that paying pursers according to the number of men on their ship "gave them a powerful incentive to inflate the numbers by false mustering, often in league with captains who pocketed the corresponding wages."45

Pepys redesigned the system, reverting to the pre-Civil War system which placed the ship's pursers back in the role of purchasing and maintaining the victualling of the ship.46 Under Pepys' changes, their duties included issuing fresh food purchased locally when in port and giving the men money to buy their own fresh food so that the more expensive sea victuals could be reserved for use at sea. Pepys' "system was designed to cause the purser to lose rather than gain by defrauding men of their victuals, and to put the captain on the men's side rather than the purser's if they had a grievance. Though by no means perfect, this system of pursery was an enormous improvement on the fundamentally corrupt and exploitative system of the Parliamentary and Republican Navy"47.

Artist: Claude Lorain - Port au Soleil Couchant (1639)

In December of 1677, the detailed Victualling Contract spelled out what food and related supplies were to be provided including alternative foods, how they were to be issued and stowed and how spoiled food was to be handled, among several other details that impacted the pursers.48 An explanation of the pursers 'necessary

money' was also included in this contract, a policy continued during and beyond the golden age of piracy.

However, as historian J. R. Tanner points out, "arrangements for issuing the victuals were somewhat

complicated, and appear to have been designed to prevent pursers

having command of cash." Sea victuals were provided under the warrant "of 'the lord high admiral, or lords

of the admiralty for the time being,' or three or more of

the navy board, or 'the commander in chief of a fleet or

squadron,' or 'the particular commander of any ship in cases

not admitting of the time requisite for procuring any of those

before recited.' Victuals supplied while a navy vessel was in port were to be under the warrant of the port's 'clerk of the check and master attendant,

where any is.'"49 The purser was given ready money only when a ship's voyage involved 'foreign service' "in which case, and that

only, the purser shall receive from the said victuallers ready

money" under their warrant.50 (This clause later caused all sorts of trouble and was modified repeatedly in an effort to avoid cheating by the pursers and captains acting as pursers as we shall see.)

N. A. M. Rodger suggests, "Pepys's most important and lasting contribution to the victualling system was a reform of the system of pursery."51 Even so, a report written around 1673 by Captain Stephen Pyend of the 4th rate Ruby made during the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672-4) mentions the "practice of pursers entering men in their sea-books some days before their being really in the ship, and also not discharging them till some days after gone from the ship, the like as to those that die or run away"52. Even the implementation of the 1677 victualling contract and its efforts to assure quality foods were issued by victuallers did not solved such problems. Complaints of delays, improper cuts of meat, moldy bread and other victualling problems started coming in in March of 1678.53 Although the victualling system got better under Pepys, it still required improvement.

1 John Leyland, "The Purser and the Seaman's Pay", The Mariner's Mirror, November 1912, p. 322 & Raymond Oliver and Jürgen Beck, Why the Captain is a Captain, 2010, not paginated; 2 Catholicon Anglicum, an English-Latin Wordbook, Dated 1483, Sidney J. H. Herrtage, ed., 1891, p. 294; 3 "bursar (n.)", www.etymonline.com, gathered from the web 3/17/21; 4 Great Britain, Fifth Report of the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, Part 1, 1876, p. 528; 5 See for example "The Expenses John Howard, Kt." (1463 & 1466 entries), Manners and household expenses of England in the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries, illustrated by original records, 1841, p. 188 & 209 & "Receipt by John Paynter" (1470-1) & "A Draft of a Signal Manual" (1472), Letters of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries from the Archives of Southampton, R. C. Anderson, ed, 1921, p. 13; 6 Michael Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, 1896, p. 41-2; 7 Commander R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 252; 8 Oppenheim, p. 35; 9 David Loades, The Tudor Navy, An Administrative, political and military history, 1992, p. 34; 10 His Majesty's Stationery Office, Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 1, 1509-1514, 1920, pp. 921, 1032, 1034-5, 1095,1222, 1237, 1497 - 1500, 1501 & 1507;11 Oppenheim, p. 75; 12 Oppenheim, p. 83;13 Oppenheim, p. 82; 14, 15 Loades, Tudor Navy, p. 86; 16 Loades, Tudor Navy, p. 203; 17 'Baeshe's contract for victualling - BL, Cotton MS Otho E. IX, ff. 99-102v, 116-19, 13 April 1565', Elizbethan Naval Administration, C. S. Knighton and David Loads, eds, 2013, p. 596; 18 Loades, Tudor Navy, p. 208; 19 Oppenheim, p. 393; 20 Oppenheim, p. 397; 21 Oppenheim, p. 392; 22 Oppenheim, p. 192; 23,24 Oppenheim, p. 193; 25 Andrew Derek Thrush, "The Navy Under Charles I, 1625-40", Doctoral Thesis, Richmond upon Thames College, 1990, pp. 162-3; 26 William Monson, The Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson, Vol. IV, M. Oppenheim, ed., 1913, p. 60; 27 J. R. Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy from the Restoration to the Revolution", The English Historical Review, Vol. XII (1897), p. 42; 28 N. A. M. Rodger, The Wooden World, 1986, p. 130;29 Oppenheim, p. 287; 30 Oppenheim, p. 356; 31 Oppenheim, p. 356, J. R. Tanner, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 24 & William Monson, The Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson, Vol. IV, M. Oppenheim, ed., 1913, p. 20; 32 Oppenheim, p. 356; 33 N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, A Naval History of Britain, 2006, p. 106; 34,35 Oppenheim, p. 286; 36 Andrew Derek Thrush, "The Navy Under Charles I, 1625-40", Doctoral Thesis, Richmond upon Thames College, 1990, pp. 140-1; 37 W.G. Perrin, "Introduction", Boteler's Dialogues, 1929, pp. xii-xiv; 38 Nathaniel Boteler, Colloquia maritima or Sea Dialogues, 1688, p. 20-21; 39,40 Sir William Monson, Naval Tracts, Vol. IV, 1913, p. 55; 41 Monson, p. 57; 42 Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy...", Vol. XII (1897), p. 34; 43 Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy...", Vol. XII (1897), p. 30; 44 Samuel Pepys, Pepys Diary, November 22, 1665; 45, 46,47 Rodger, Command, p. 106; 48 For an extensive look of this contract, see Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy from the Restoration to the Revolution: Part II 1673-1679", The English Historical Review, Vol. XIII (1898), p. 32-9; 49 Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy... Part II 1673-1679", Vol. XIII (1898), p. 34; 50 Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy... Part II 1673-1679", Vol. XIII (1898), p. 34-5; 51,52 Rodger, Command, p. 105; 53 Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy...", Vol. XII (1897), p. 41