Organizing Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Next>>

Organization of Ship's Food In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 4

Naval Victualling Procedures Overview, Continued

Victualling Commission Under Queen Anne (1702-1714)

During 1702, Anne became queen of England and the War of Spanish Succession began. This created new opportunities and challenges for the Victualling Board.

Artist: Godfrey Kneller - Queen Anne Before She Ascended (1694)

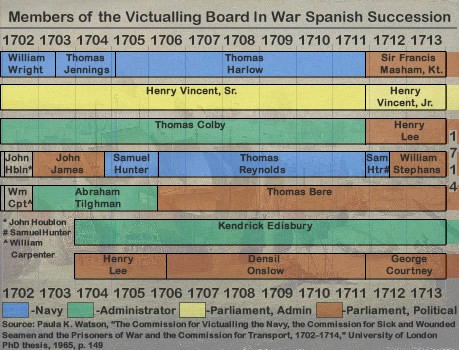

Upon Anne's ascension, three of the existing five members of the Victualling Board were replaced (likely because of the change in leadership, a common occurrence.) In addition, two more Victualling Board positions were created in 1704, increasing the total number of commissioners from five to seven.1 Not surprisingly, some members were removed, others left or were replaced throughout the duration of the war (1702-14). A total of eighteen different people served on the Victualling Board during this period.

Historian Paula Watson provides a detailed account of the background and makeup of the Victualling Board during this period, organizing the members into four basic types. These include former navy men, career government administrators, former parliament members with administrative roots and former members of parliament with political ties.

The navy-bred members brought a wealth of experience with them, making them valuable board members, "particularly in such matters as hiring victualing ships and speeding them on their voyages."2 The members with administrative experience were often useful in building necessary government systems within the board. In a similar way, the former parliament members with administrative backgrounds provided "the backbone of the court party, often held office for long periods, becoming valuable through the experience they gained."3 This would have been useful in navigating the political systems that governed the Board. The last group were primarily political appointees who were

Members of the Victualling Board During the War of Spanish Succession

Background Image: Artist: Isaac Sailmaker - Battle of Malaga (1704)

being rewarded for their support of a party with positions. Members of this type were the most frequently added and removed of the four board member types and generally offered the least in terms of useful experience. The appointees are shown in the chart at right with the different member types color-coded for reference.

Some of the members had experience in more than one realm. For example, all the members with naval backgrounds had also served in administrative capacities or had managed victualling yards during their careers.4 And two of members do not really fall neatly into any of these four types. Watson says that one member - John Houblon - a London merchant - doesn't fit neatly into any of the four types. He was the only merchant to serve under Anne, which is not entirely surprising given that the Board continued to move away from using contracted victuallers and toward naval control of resources. Houblon only served from who May through November of 1702. Watson was also unable to find out anything board member William Carpenter who served for the same period short period, so she does not assign him to any of the four types.5

The Victualling Board was nearly abolished.

Artist: Peter Tillemans - House of Commons in Session (c. 1710)

Following the end of the the War of the League of Augsburg in 1697, the problems discussed in the previous section led some to consider returning to naval victualling by contract.6 From 1701 through 1703, members of the English government's legislature highlighted the naval failures during the previous war.

"[T]hose members of the two houses who were active in criticising the Admiralty or the boards [including the Victualling Board] were not primarily interested in improving administrative efficiency, but were trying to make political capital out of administrative failures."7 Inquiries into the naval victualling system took place in the House of

Commons in 1702 and 1710 and in the House of Lords in 1703.

While political in nature, such inquiries did highlight some serious issues within the service. At the top of the list was perennial problem of poor payment of the victualling accounts. In October of 1703, the commissioners wrote the Treasury Lord Secretary:

those who went before us in this Commission have ...left a very great part of what was incumbent on them unperformed, in the not examining those accounts: so, through a continuance of many years in this disorder, the accounts ... are perplexed and confused to such a degree as renders it now extremely difficult, if possible, to call the parties concerned to any tolerable account, either of cash or for those stores and provisions into which such cash hath been converted.8

However, the new board "brought about real improvements, especially in reducing its accounts to order, borrowing proper methods of record-keeping from the Navy Board, and starting an effective course [of payments]."9 With the establishment of this new 'course', the government began making a serious effort to pay off the outstanding debts from the previous 'course', stating that they had completed the task in 1704. The board created a position called the Clerk of the Cheque the same year, appointing Thomas James. He was responsible for working "with the [victualling yard] storekeepers in viewing the quality and taking account of the quantity of all sorts of provisions received into store" and keeping records of them.10 In their quest to improve victualling, the Board also decided to inspect their facilities regularly to make sure they were properly managed.

In August of 1710, supplementary instructions were issued by the Admiralty which assigned particular tasks to Victualling Board members. Among the assignments: Henry Vincent was to oversee the Clerk of the Meat Cutting House, the storage of meat in London and the coopers (cask builders). Thomas Harlow oversaw the Hoy Taker - the person in charge of shipping provisions to waiting vessels. Denzil Onslow inspected the bake house and

Artist: James Stewart

Packing Salted Meat (Herrings), From The Harvest of the Sea, By James Bertram (1865)

oversaw storage of bread, peas, oatmeal, and flour. Thomas Bere inspected the Clerk of the Brewhouse's office at St. Katherine (near Tower Hill), examining the beer, malt and hops.11 The others board members responsibilities were related to victualling office management and accounting.

Some modifications were made to the sailors' diet in 1703, prompted by a House of Commons Committee suggestion that sailors should be issued fresh food while in port. The Victualling Board wrote to the House Committee explaining "there is this difference between harbour, or 'petty warrant', and sea victuals, viz. the bread and beef spent in harbour is delivered, the former in loaves, the latter fresh"12. They explained that fresh provisions were provided at naval outports, and "constant care is taken in the respective ports of the West and East Indies, by [local victualling] agents, credits, or correspondents, to pay the short-allowance money due to every seaman in person, which [the seaman] is at liberty to dispose of himself to his best satisfaction."13 In other words, cash was given to sailors in lieu of their full allotment of provisions ('short-allowance money') so they could buy whatever they wanted to eat when in foreign ports. (It is notable that most navy sailors' accounts mention using this money to buy alcohol. Navy sailor's food purchases in port are mentioned much less frequently.)

In January of 1704, Anne's husband Prince George confirmed this by issuing orders requiring navy

Whole Meal Oat Groats

vessels "to be victualled while they are in any port or road of England or Ireland... with two days in the week fresh meat one day in lieu of salt meat and the other in lieu of salt

pork."14 The victuallers didn't like this new order, pointing out how difficult it would be for them to have a ready supply of fresh meat and bread on hand for an unknown number of ships which might be in harbor. Nevertheless, the order established this custom for navy vessels in port going forward.

A later modification to the navy diet concerned oatmeal, something which could be substituted for fish according to the 1700/1 Victualling Instructions. The specification for oatmeal was changed to whole meal in 1714. The sailors didn't care for oatmeal, "probably because it quickly bred maggots."15 Historian R. D. Merriman explains that unrefined whole meal (also called groats) didn't suffer quite as badly from this problem.

Artist: Claude Lorrain

Porto di Mare, Effetto di Nebbia (1646)

An important part of the victualling process and the Victualling Board's duties was the purchase and processing of food. Watson provides a fairly detailed explanation of how the various sea store food items were purchased by the navy between 1703 and 1709. It is worth examining because it gives insight into navy food purchasing during the Golden Age of Piracy.

Annual contracts were established for butter and cheese. In 1703, four contractors bid for this contract which Richard Maundrell won with the lowest bid. He supplied butter at 3-1/2 pence per pound and cheese at 1-3/4 pence per lb. The butter and cheese quote included transportation directly to the ships being victualled because it would rot if stored in the warehouses if left there for any period. Maundrell supplied both commodities to the navy until 1709.16

Semi-annual contracts were established for beef, with a typical order for 1000 beeves being placed in the Autumn and a second, smaller order for 50 to 200 placed at the beginning of the year. Meat was usually purchased in the fall and early winter as mentioned previously. Unlike the butter and cheese contract, beef contracts were given to a variety of vendors. For beef, London specified that animal had to be more than six hundred weight, while the outports would accept animals of five or five and a half hundred weight.17 Around 12,000 hogs were purchased in the winter of each year, usually from both large and small vendors. The navy was to be supplied with 1,000 hogs per week at the London Tower location which they slaughtered. The minimum acceptable weight was 96 pounds per hog.18

Artist: Balthazar Nebot -

Covent Garden Market (1737)

Oatmeal contracts were typically placed in the fall and winter in quantities which varied from twenty to four hundred quarter tons. Several vendors supplied oatmeal; in 1704 there were fourteen different oatmeal vendors. Delivery to the London yard was expected to be within two months or less.19 Contracts for peas were similar, being made with several vendors between fall and early spring. In 1704 there were eleven pea contractors. Orders quantities varied between twenty and two thousand quarter tons and were expected to be delivered quickly. Flour orders were similar, employing nine contractors in 1704 with orders ranging between twenty and two hundred and fifty quarter tons. Flour was usually ordered in the winter and early spring.20

Although the navy had their own bakery, they weren't always able to supply enough biscuit. When needed, biscuit was purchased throughout the year, although the largest orders were placed in the winter and the spring. In 1704 there were thirty-six bread contractors with a small group of big bakeries providing the majority of the biscuit used on ships. "The predominance of a small group was possible because although most of the bread contractors were themselves the owners of bakehouses, selling their own product, some of the larger bakers, bought up other people's bread to sell to the victualling board as well as their own."21 Wheat for the King's mills was also purchased, most often in the winter and spring.

Artist: George Stubbs - Reapers (1795)

For the most part, the London markets were large enough that the navy's large purchases generally didn't affect food prices. However, some impact on meat, pea and oatmeal markets was felt during war times when the navy's demand was unusually large.

Some foods were purchased at English outport victualling locations which had a greater impact on the local market than in London. This was primarily because the markets were smaller than London. "Certain local brew-houses and bakehouses, which were able to establish a virtual monopoly of trade with the victualling board, grew rich on naval contracts, which gave them a bigger market than they would otherwise have been able to enjoy."22

Of course, the biggest challenge for contracted victuallers was figuring out how much food they should have on hand. Sudden, unplanned increases in orders during war required victuallers to scramble to procure food. It was particularly challenging to purchase these foods outside of the normal harvest season. Cancelled attacks could result in food being left at the victualler's storehouses for long periods. While dried and salted foods kept longer than fresh foods, they still went bad if stored for too long, so excess supply resulted in waste for which the victualler had to pay. Naturally, the uncertainty the Victualling Board faced while estimating the number of sailors for each upcoming year during the War of Spanish Succession resulted in food shortages and surpluses which the victuallers had to deal with as best they could.

The board issued procedural instructions to some of the officers below them in 1710 including the Masters or clerks of the slaughterhouse, meat cutting house, brewhouse, bakehouse and cooperage.23 The instructions are quite specific, explaining the officer's duty and how the victuals they oversaw were to be treated and processed. Some of the instructions can be found here

Artist: William Pratt -

Floating the St. Albans at Deptford on the Thames (1750)

in the section on the Tower Hill victualling location.

The location of the War of the League of Augsburg also created a new problem for England. London was the center of the victualling organization because this allowed the navy to purchase victuals from a few large victuallers rather than several small ones. This helped make both food supply and food prices more predictable. Unfortunately, London was not in as good a position as the southern English outports to supply victuals to ships going to war in France.

The outports presented several other problems for victualling the fleet. The markets there were smaller and less able to sell to the navy on credit because they couldn't wait for their money like bigger vendors could.24 They also lacked the storage space and provision processing facilities needed to run victualling operation. Supplies were shipped from London to the outports, which opened the transport vessels up to the twin problems of unpredictable weather and enemy privateers. Because of this, victual transport and storage became part of the Victualling Board's concerns. Up until this time, the board had hired hoys (barges) as needed to deliver victuals to waiting ships. This new demand caused them to start purchasing vessels to carry supplies and to serve as floating storage units. The first two vessels purchased were captured enemy galleons which were sent to Portsmouth, one of the main ports used to supply ships during this war. The Victualling Board explained to the Navy Board that the galleons would

. Deptford, 1709.jpg)

Plans of English Storage Hoy Lyon (Lion) Built for Deptford Yard (1709)

be placed [in Portsmouth Harbor], the largest as near the victualling storehouses as possible for the [victualling] agent's convenience in receiving and issuing such provisions as shall be sent from hence or any other port, by the not landing whereof a very great charge in labour and cartage will be saved, so will the smaller ship be laid as near to the docks as may be for taking in the remains of victualling from such shipping as may be docking and refitting, to be returned on board them when ready.25

The board continued to purchase vessels for this purpose. They wrote the Secretary of Admiralty in June of 1708 explaining that

if her Majesty had four hoys of her own at the port [of London], of about 50 tons each, [they] would constantly be employed in carrying provisions to the men of war in the River Thames and Medway; whereby a great part of the freight now paid at this port, amounting to near £6,000 a year, would be saved to her Majesty, and the said vessels would likewise be ready on all extraordinary occasions to go abroad, and thereby prevent the inconveniences we are now under from the want thereof.26

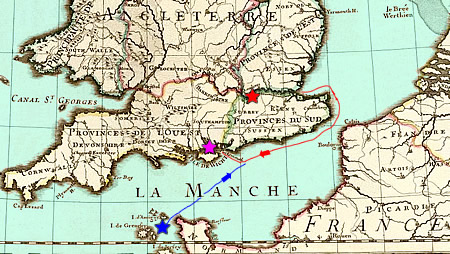

Map of English Victualling (Red) and French Privateer Blue) Routes

Map Cartographer: Guillaume de L'Isle - Map of English Isles (1702)

This and several subsequent requests for transports were approved. By 1712 the board had six vessels at Portsmouth, five in London, three at Plymouth, two at Chatham, two at Dover, one at Harwich, one at Lisbon, Portugal and two at Port Mahon, Spain.27 It helped solve the twin problems of transport and storage of victuals.

This left the problem of protecting ships transporting goods from London to southern ports. French privateers preyed on English merchant and naval transport ships making this journey. Many of the victualling vessels sailed from London (shown on the map at left as a red star) to Portsmouth (the purple star), the best port for victualling navy vessels for this war. French vessels attacked from the Guernsey and Jersey Islands (blue star) attempting to capture these ships and their provisions. To protect against this, the navy sent warships along with convoys of victualling and merchant ships to prevent attacks. However, this meant that the convoys had to wait for favorable weather, the assembly of a sufficient number of victualling ships and the availability of navy ships to accompany them. "As a result of all this the victualling ships were often three, four or even five months getting from London to Portsmouth."28

.jpg)

Artist: Abraham Allard - Ratification of the Treaty of Utrecht May 12, 1713 (18th century)

France signed a peace treaty with England in October of 1711. A series of other peace treaties followed, with the main Treaty of Utrecht being signed in April of 1713. Because of the large number of countries involved in this war, negotiations continued to take place in an effort to create treaties between the all the various nations. The final treaty was signed between Spain and Portugal in February of 1715.

However, the English involvement in fighting had slowed and practically ceased by 1712. With this development, the navy began to be reduced in size and the strain on the Victualling Board was gradually relieved. Anne died in August of 1714.

1 "Victuallers to navy board, 4 Sept. 1703, Adm 110/2", cited in Paula K. Watson, "The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714," University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p. 152;23; 2 Watson, pp. 297; 3,4 Watson, p. 300; 5 For a much more detailed exploration of the Victualling Board's members, see Watson, pp. 297-314; 6 Watson, p. 47; 7 Watson, p. 50; 8 'Commissioners of the Victualling to Secretary of the Lord Treasurer - 30th October 1703', Cited in Commander R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 267; 9 N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, A Naval History of Britain, 2006, p. 213; 10 Watson, p. 149; 11 'Admiralty to Victualling Board - 14th August 1710', Cited in Merriman,p. 297; 12 'Commissioners of the Victualling to a Committee of the House of Commons, December 1703', Cited in Merriman, p. 269; 13 Merriman, p. 269-70; 14 'Victuallers to Navy Board 14 Jan. 1703/4, Adm 110/2, p. 128', Cited in Watson, p. 153; 15 Merriman, p. 249-50; 16 Watson, p. 100; 17 Watson, pp. 101-2; 18 Watson, p. 102; 19 Watson, pp. 104-5; 20 Watson, pp. 05; 21 Watson, p. 106; 22 Watson, p. 110; 23 See Watson, pp. 75-86; 24 Watson, pp. 99 & 116; 25 'Victuallers to navy board, 15 Mar. 1702/3, Adm 110/2 p. 8-9', Cited in Watson, p. 147; 26 'Victualling Board to Secretary of the Admiralty - 23rd June 1708', Cited in Merriman, p. 286; 27 Watson, p. 147; 28 Watson, p. 117

Victualling Commission Under King George I (1715-1725)

Anne was succeeded by George I of Hanover in August, 1714. As before,

Artist: Godfrey Kneller - King George the First (c 1714)

when the monarch changed, so did the appointees to the Victualling Board. All but Thomas Bere and Henry Vincent, Jr. from Anne's reign were replaced. both Two previous members of the board, Thomas Reynolds and Denzil Onslow, were restored and three new people were brought in. These included Robert Arris, Peter Jayes and Waller Bacon.1 Because there was no war during this period, the board focused more on the administrative aspects of the job than they did on diet and supply.

The duties assigned to each board member were revised in 1715 so that each member of the Victualling Board was responsible for a single department. They modified and reissued the 1710 instructions for the officers supporting the board in 1716 including the victuallers and various people in charge of food preparation at Tower Hill. "There was no change in the essentials of this already ancient technology, but packing in summer was forbidden, while close attention to detail, and to the highest quality of raw materials (notably salt), yielded a sharp fall in complaints of spoiled meat."2 Pickling and packing meat in the summer was more likely to result in deterioration than if it were packed in cooler temperatures. "The basic instructions, supplementary instructions of 1715, and a detailed set of instructions for subordinate officials compiled by the Victualling Board in 1716, taken together, were the constitution of the victualling service in the eighteenth century."3

The payment of contracted victuallers using the 'course' continued to be problematic. The Victualling Board was instructed to examine the accounts on the two payment 'courses' which had preceded their tenure. They found "accounts unadjusted and imprests uncleared ever since the year 1683, the time the victualling was put into commission" which amounted to the staggering sum of £816,192 14 shillings and 4 pence.4 This is odd because the board under Anne claimed to have cleared all the overdue accounts from the first 'course' by 1704. It is possible they overlooked some long overdue accounts. The previous board's efforts were not entirely lacking, however. The new Victualling board found that records of the accounts kept since 1706 were much better organized and paid.

The Victualling Board assured the Admiralty Secretary in February, 1715 "that our utmost endeavours shall not be wanting towards the examining and adjusting the said accounts and clearing as many of the imprests as we shall be enabled by proper vouchers for that purpose."5

Artist: Florent Willems - The Accountant (1849)

However, they also noted that it would be difficult to settle some of the very old accounts, noting that they were concerned about cheating due to 'loose and unjustifiable' oversight in the past.

In addition to improvements in accounting begun in 1706, the new board found "some steps were made towards a regulation in the management of the victualling, as the giving instructions to the several [Victualling] Agents ... and the keeping a cheque on them as well as on the [outport] Storekeepers and correspondents". Control of the agents and storekeepers had improved with the implementation of the 1710 supplementary instructions.

Building on the steps taken to better regulate the system, the new board implemented some new policies focused on the overseas English Navy victualling. They explained to the Admiralty Secretary that victualling in foreign locations had been "attended with very irregular proceedings, by the commanders frequently taking upon themselves the sole management of the providing provisions for victualling their respective ships, whereby the advantage to the Crown from their being cheques on the pursers ...has been entirely lost"6. This, they said, led to 'many extraordinary charges' for victualling.

There was significant resistance to the changes the Board made by commanders who were used to cheating the system by purchasing unnecessary amounts of victuals from non-sanctioned victuallers overseas.

Many a [navy sanctioned] contractor complained that the captains would buy from them only the more expensive products, and that they continued to buy other goods - those on which a profit could easily be made and hidden - elsewhere. Some captains did not even bother to go to a contractor's warehouse, claiming that the urgency of the situation required putting in at the closest port of call in order to stock up on provisions.7

In addition, purchasing extra food and intentionally damaging the contents allowed them to return the now spoiled victuals for credit on their account when they sailed back to England. The board also accused the commanders of practices such as hiring boats to transport victuals from land when they could have done this themselves and repairing casks when there was no need to do so. Although they don't explain the reasons for such thing, they appear to suspect the commanders of creating charges not actually performed.

Because of the loose management of overseas victualling, the Victualling Board implemented several new procedures. Among other things, the board ordered:

Artist: Isaac Sailmaker - The Royal Yacht off Sheerness (c. 1688)

• Commanders to take 8 months of provisions with them from England.

• Ships to go on short allowance 'upon leaving England'. This meant six men ate the provisions normally given to four men each day, making their sea provisions last longer and reducing the need for victualling overseas.

• Victuals to be purchased only from navy approved victualling agents who sold provisions at navy-approved prices and accepted bills issued on the 'course' rather than cash.

•Ship's commanders were not to be involved in purchasing victuals, only in verifying the victuals which the purser purchased were sound and the quantities correct.

• Documents specifying local prices and exchange rates were to be drawn up and certified by the local governor and 'eminent merchants of the place' when it was necessary to purchase victuals from non-navy sanctioned vendors.

• Care was to be taken to stow provisions on the ships to prevent damage.8

The ship commanders resisted these changes because it would curtail what they felt were a reasonable supplement to their incomes. More than a year after these policies had been established, the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty

repeated their orders to the commanders of all her Majesty's ships now abroad (as they will do to those which shall be sent to remote parts for the future), by which they are strictly required not to purchase stores of any kind or provisions, but what there shall be an absolute necessity for their so doing; and then to take particular care it be at the best rate of exchange for her Majesty's advantage.9

Only after seven years of "repeated Admiralty orders did the new policy become established. Thus in the largest of the royal navy's overseas domains the business enterprise of the cruising captains was sharply curtailed."10

In practice, taking eight months of provisions for oversea voyages could be problematic. In January of 1718, the naval commissioners asked the Victualling Board to provide victualling for 10,000 more men, three months after the normal declaration of men to be victualled. In March, the Victualling Board wrote that such a large request so late in the season would be hard to fill. They suggested "that instead of our furnishing these several ships before mentioned with eight months flesh, we may ...reduce the quantity to six months, seeing it will be otherwise impossible for us at this season of the year to make a sufficient addition to the flesh already in store to answer what the service may call for "11. This would require the ships to victual overseas. However, the Victualling Committee had decided to work with some private contracted agents who would provide victuals at established prices in places not used by navy ships often enough to require a full victualling yard in 1715, which gave them more ability to handle such a situation. "Victualling contracts were drawn up in this way in Dublin [October, 1716], then in Barbados, New England, New York, Virginia and Maryland [November, 1715 and February, 1718]."12

Artist: Edward Barlow - Port Royal, Jamaica, From Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea (c. 1677)

In addition to the difficulty of fulfilling the January 1718 order for eight months provisioning, the board pointed out that ships did not have enough space for all the extra food, "and the butter and cheese not holding good for a longer time in those hot countries, it will therefore be absolutely necessary that a timely provision be made abroad" at Lisbon by their victualling agent.13

Even when the new eight month requirements were followed, ships still had to revictual while overseas at times. Food went bad or ran out during overlong voyages. This was particularly true for ships traveling to the West Indies.

Fairly permanent victualling sites with dedicated victualling agents were established in the Mediterranean, as highlighted in the article on English Royal Navy Victualling at the Outports and By Ports. "The Victualling Board considered its facilities at Port Mahon and Gibraltar to be permanent and worth maintaining regardless of fleet activity, but it did not always have an Agent in residence there. Normally there were no Agents in America or the West Indies during this period [1715-50]"14. Instead, private contractors who agreed to acceptable terms were selected for the Caribbean. Their use "was a recognition of the problems of supply over long distances. They employed merchants with the capacity to ensure the supply of provisions through well-established private connections throughout the Atlantic World."15

Fortunately, because this was a period of peace, there were fewer victualling issues than in the previous twenty-five years. Less drastic changes were required to make the victualling system work. There were also fewer official complaints about the food by the sailors. This was probably due in part to the fact that there were fewer sailors. As a result, there was also less strain placed on the victuallers who weren't forced to scramble to suddenly procure unexpected quantities of food.

1 Paula K. Watson, "The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714," University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p 311; 2 N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, A Naval History of Britain, 2006, p. 304-5; 3 Daniel A Baugh, Naval Administration 1715-1750, 1977, p. 401; 4,5 'Victualling Board to Admiralty Secretary - 22 February 1714/5', Cited in Baugh, p. 407; 6 "Victualling Board to Admiralty Secretary - 17 June 1715", Cited in Baugh,pp. 410-11; 7 Christian Buchet, The British Navy, Economy and Society in the Seven Years War, 2013, Translated Anita Higge and Michael Duffy, p. 21; 9 "Secretary of the Admiralty to Navy Board 9th October 1711", Commander R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 47; 10 "Victualling Board to Admiralty Secretary - 17 June 1715", Cited in Baugh, p. 409; 11 Baugh, p. 402-3; 12 Buchet, p. 20; 13 'Victualling Board to Admiralty Secretary - 13 March 1717/8', Cited in Baugh, p. 420-1; 14 Baugh, p. 402; 15 Douglas Hamilton, "Private enterprise and public service Naval contracting in the Caribbean 1720-50", Journal for Maritime Research, 2004, p. 39

Other Victualling Procedures

In the late 1720s, Thomas Corbett collected all the various naval instructions, rules and precedents that had been made up to that time and published them in 1731 as Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea.1 While this is six years after the end of the period of interest, historian N. A. M. Rodger points out, these "were largely a codification of orders issued at

Victualling Board Flag,

From 'Plates Descriptive

of the

Maritime

Flags of All Nations',

By John William Norrie (1832)

various dates in the past as far back as 1663"2. They are very detailed, but because they reiterate a lot of what has already been discussed, most of the information is not included here. However, there are some procedures not discussed in the preceding sections which were likely employed during the period of interest. Most of these concern damage to provisions on the ship. The Regulations ordered:

XIII. When any Vessels come on board with Provisions, or other Stores, they are not to be suffered to loyter by the Ship's Side, but forthwith to be unladen and sent away; nor shall the Captain of one Ship stop a Vessel that is consign'd to another Ship, or take out any Part of her Lading.

XIV. All Supplies of Provisions are to be put on board the Ships, without any Charge to the Purser for Lighterage Porterage or otherwise and with all the Dispatch possible; and the Masters of the Vessels or Lighters by whom the Provisions are sent shall see the same put into the Slings or Tackles of the Ship they are consigned to, by careful Men belonging to the Ship; and shall likewise deliver to the Captain a perfect Bill of Lading under the Hand of the Victualling Officer, that he may see if the whole is brought on board.

XV. If any Provisions slip out of the Slings, or are otherwise damage or lost by Malice and Carelessness of the Ship's Company, the Captain is to charge the Value against the Wages of the Offender, and give a Certificate to the Purser, expressing how the same happened, with the Name of the Offender, and the Summ charged against him, that the Purser may be allowed it on his Accounts.3

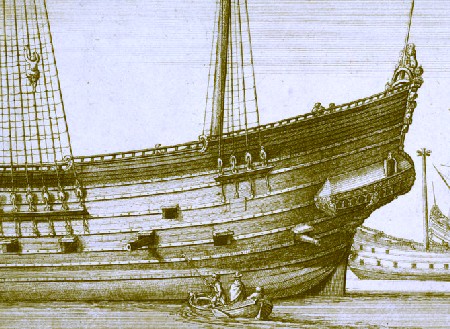

Artist: Wenceslaus Hollar

Preparing a Ship to Sail, From Navium variae Figurae et Formae (1647)

Such rules were implemented because the purser received a credit for victuals that went bad while at sea and the navy was trying to prevent both carelessness in keeping them and intentional damage that required them to credit the purser. Even when the provisions were damaged, the Regulations ordered that when "the Bread [biscuit] proves damp, ...have it aired upon the Quarter Deck or Poop; and [the ship's officers are] also to examine the Flesh Cask, and if any Pickle [salt solution] be leaked out, to have new made and put in, and the Cask made tight and secure."4

Finally, as established in 1704, ships in port were to receive fresh meat twice a week. These instructions stated that "Three Pounds of Mutton are to be accounted equal to a Four Pound Piece of Beef, or to a Two Pound Piece of Pork with Pease."5 It is interesting that the fresh loaves of bread which the 1704 orders specified are not mentioned here.

1 Anne Byrne McLeod, "The Mid-Eighteenth Century Navy From The Perspective Of Captain Thomas Burnett And His Peers", University of Exeter Doctoral Thesis, 2010, p. 132; 2 N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, 2004, p. 320; 3 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea,1st ed, 1731, p. 64-5; 4 Regulations, p. 66; 5 Regulations, p. 67