Organizing Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Next>>

Organization of Ship's Food In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 9

Officers In Charge of Food - Ship Pursers, Continued

A Foundation For Cheating

"A purser's salary was not nearly equal his responsibilities, and the system practically required him to twist the regulations- to say no worse- if he were to remain solvent." (Daniel A Baugh, Naval Administration 1715-1750, 1977, p. 405)

While the purser's position certainly provided opportunities for dishonest men to cheat the purserage, the system itself inadvertently incentivized such behavior. Several things

Frontispiece From West Indian Atlas, Thomas Jeffreys (1783)

already mentioned are relevant. First, upon receiving the provisions and goods for a ship's voyage, pursers were immediately made fiscally responsible for them. Their financial burden was such that each purser had to have two guarantors on file with the navy in case he defaulted on the money 'loaned' to him. Second, when the ship ran short of provisions in a location where he could not supply them under payment using the 'course', the purser had to use his own cash to remedy the situation and apply for reimbursement at the end of the voyage.1 When this happened, he was not reimbursed at the rate he paid, but at the price the Navy Board had established with their Victuallers, which was usually lower.2 Third, pursers were not paid until their accounts were reviewed and passed by the navy. Once passed, the purser, like everyone else, was paid in 'course', further delaying his receipt of the money. N. A. M. Rodger's reviewed the official records of payment to pursers in 1759, finding delays at that time were between six months and fifty-seven years!3

Several other factors contributed to a purser's propensity to cheat the system. When the sailors consumed more food or beer than had been allotted during a day (according to the navy's prescribed menu), the purser would owe the navy for the cost of the excess consumed. He had to find a way replace this or lose money. If the purser's records were lost for any reason, such as the sinking of the ship, he was held responsible for any provisions for which he didn't have records of consumption.4 The only cash a purser received after his accounts were passed was his tobacco money and his wages.

"The financial risks which had to be incurred by a purser were considerable. So also were his opportunities for dishonesty, under a system which put him in the position of a contractor afloat, rather than that of an accountant officer."5 Such opportunities were increased by the distance pursers had from authority during foreign voyages. In addition as the quote leading this section indicates, pursers were not well paid, so they looked for ways to improve their financial situation. This could be done in both legitimate and illegitimate ways.

1 R.D. Merriman, The Sergison Papers, (Naval Clerk of Acts), 1950, p. 238; 2 N. A. M. Rodger, The Wooden World, 1986, p. 89; 3 Rodger, p. 96; 4 Rodger, p. 94; 5 Merriman, The Sergison Papers, p. 238

'Legitimate Cheating' by Navy Pursers

The navy built a 'legitimate' cheat into the purserage which,

Frontispiece From West Indian Atlas, Thomas Jeffreys (1783)

over time, came to be recognized as a way to protect the purser from some of the inevitable loss of provisions during a voyage. When a pound of provision was received shipboard, the purser was charged for 14 ounces, the two 'free' ounces being "intended to cover unavoidable wastage"1. (This was later to become known - somewhat derogatorily - as 'the purser's pound'.) The provision of an eighth share dates at least back to 1673 or 4 (and, by implication, well before) as explained in a document written by former purser Stephen Pyend (or 'Pine' as he is referred to in the document in the Pepysian library). It is summarized thus by historian J. R. Tanner:

It was the custom of the purser to leave one-eighth part of the victuals on shore, and receive the value from the victualler in money, on the ground that the 'necessary money' allowed by the king 'to provide necessaries, viz. wood, candle, platters, cans, spoons, &c, for boiling the meat, and the seamen's use in eating thereof, is not sufficient to defray the cost and charges of the said necessaries.' In serving out their allowance to the men he would make an 'abatement' of 'one-eighth part less in weight and measure than the king allows' in the biscuit, beer, butter, cheese, and pease.2

It is interesting that the reason Pyend gives for the purser's share is quite different than what is mentioned by authors talking about the period twenty years later. Nevertheless, the tradition of allowing the purser an eight of his provisions remained for decades after the end of the golden age of piracy.

Artist: Gustav Dore - Crew Offering Food, From Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1876)

Historian Reginald Merriman points out that "the purser was entitled to dispose of surplus provisions on his own behalf"3, which meant that if he was able to preserve the 1/8 of the provision that was expected to be lost through waste, deterioration or other means, he could sell it or return it to the navy for credit on his account at the end of the voyage. (But only after the other seven-eights of the provisions minus the portion consumed were returned.) This encouraged pursers to properly store provisions and preserve them against waste and damage.

It had other effects, however. The eighth share allowance became such an accepted part of the purser's reimbursement that they began claiming 'spillage' and 'wastage' during a ship's voyage despite the fact that this was why they had been given their eighth part of provisions.4 Of course, like Pyend, the navy may have thought by that time that the purser's pound provided him with necessary money resulting in their allowance of purser's loss claims.

1 Commander R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 253; 2 Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, Vol I, JR Tanner ed, 1903, p.161; 3 R.D. Merriman, The Sergison Papers, (Naval Clerk of Acts), 1950, p. 238; 4 Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, p. 253;

'Illegitimate' Cheating by Navy Pursers

Several examples of how the pursers cheated the system (and the men) were discussed in the section on the history of pursers. One of the goals of the Victualling Commission created in 1683 was to eliminate these practices, something briefly examined in the section on the pursers duties and procedures. Yet pursers still managed to find ways to cheat during the golden age or piracy, resulting in the Victualling Commission and navy administration expanding their instructions and enforcement of procedures to curb such practices. This section looks at period examples of the ways that pursers cheated and some of the rules that were created to stop them.

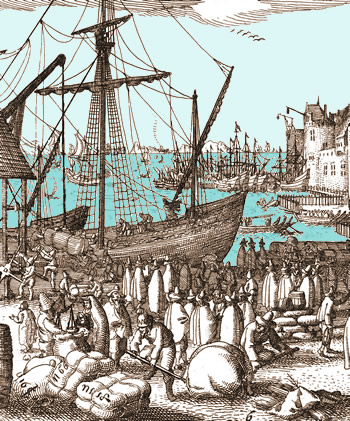

One way the purser could cheat involved variations on selling provisions that were meant for a voyage. Nearly a decade after the Victualling Commission took charge, the Navy Board wrote the Admiralty of an 'illegal, irregular and unusual practice'

Artist: Julius Caesar Ibbitson - Sailors Carousing (1802)

where pursers were "selling provisions out of their Majesties' ships; we are of opinion it will be very necessary an adjustment should be made of the prices the pursers shall pay to the officers and seamen for short provisions, that so they may be at a certainty, and the colour of selling provisions under that pretence taken away."1 To work this cheat, the sailors voluntarily placed themselves on short allowance, accepting short allowance money in its place upon arriving in the next port. The purser could then return the unused victuals for credit.2

Another variation involved the men going on short allowance and allowing the purser to sell what they didn't consume in exchange for a portion of the proceeds. (This again provided the sailors with a way to receive cash in advance which they could spend however they wanted upon reaching port.) A court martial was held aboard HMS Neptune on May 17, 1694 over such a case. In the end, it was not deemed illegal, ruling that the men were entitled to do what they liked with their share of provisions not consumed since it was their property.3 It is interesting that they did not charge the purser for falsifying his records of food consumed.

Some pursers made 'unofficial' arrangements to accept the cash equivalent of provisions in lieu of the provisions themselves from a victualler, so that the purser could buy the necessary provisions in a foreign port. Here, the cheat would only work when foreign victuals were cheaper

Artist: Claes Visscher II - Loading a Ship, Handel en koopvaardij, (1608)

than the amount the navy allowed. The Navy Board suggested to the Navy Secretary that this practice should be prohibited. However, in the same letter, they admitted that "whilst the pursers' balance bills are so ill paid it is impossible they should comply... and, we doubt, not very easy to restrain them from selling provisions out of the ship."4 Unfortunately, this didn't work well in practice and pursers ended up paying more for the victuals in foreign ports than the cash they received. "Too often, the money was misappropriated, victuals ran short, and ships had to return to harbour, when on paper they should have had several weeks' provisions in hand."5

Sometimes the purser remained on shore after the ship had left in order to sell the provisions he had been provided, but hadn't loaded onto his ship. The Admiralty noted that pursers claimed they had been left behind because the victuals hadn't been sent on time, suggesting they had no choice but to sell them, rejoin the ship at another port and make up the difference there. The Admiralty ordered the Commissioners of Victualling to give "the respective captains of those ships an account of what quantity of each specie of provisions they intend to put on board them... whereby the captains may ...inspect whether the whole of the said provisions is brought on board; to be a check upon, and thereby the better restrain the pursers from disposing of any part thereof."6 They added that money which had previously been given to the pursers for buying short beer in foreign ports should now be given to the ship's captain so that he could give it to the purser after the ship left port, apparently a further incentive for the purser to be aboard when the ship left.

Changes to the Victualling Instructions in January of 1701 added several new rules designed to prevent cheating by pursers, one of which echoed the order to give all short beer money to the captain. After these rules were published, all money which had previously been given to the purser was now to "be put into the hands of the captain, that so it may not be made use of, on any pretence whatsoever, till they shall arrive at the place where such provisions must be purchased; and then the purser to apply to the captain for the same."7 The purser was to provide a receipt for such purchases, attested to by other ship's officers after inspecting the provisions being brought aboard. However, the navy's preferred method for obtaining provisions overseas was still to get them at ports where there was a victualler who accepted the navy 'course' payments rather than cash.8

Another rule included in the 1701 Instructions ordered pursers not "to proceed on another voyage till such time as he shall have fairly passed all depending accounts; so are you strictly to call on them at the end of every voyage to pass their accounts for the same, which, if they do not perform

Artist: Cornelus de Wael

Officers Talking, Harbour scene with sailors on a beach, Plate 2 (1645)

within six months after the expirations thereof, they will be punished for the same by a total dismission from the Service or in such other manner as we shall think fit."9 As mentioned, many pursers during this period ended up owing the navy money at the end of a ship's voyage10 and it was almost impossible for the navy to collect their due if he had left on another voyage before his accounts had been passed.

The captain was also tasked with making sure all the provisions appointed to his ship were loaded in the 1701 Instructions, formalizing the policy established by the Admiralty in 1699. They said: "when any ship shall be victualled for the Channel service, the whole proportion of provisions ordered be put on board in specie [as specified], and ...a copy of the purser's indent be sent to the captain, that so, either by himself or such trusty person as he shall appoint, a strict inspection may be made, whether the said provisions are all delivered on board his ship"11. This was designed to prevent them from selling provisions before they were loaded and using the proceeds to purchase the replacement provisions at one of the other ports where the ship stopped.

it took the navy several years to wean the pursers from purchasing victuals for cheaper prices in foreign ports. In August of 1708, the Victualling Board reported that ships lading their provisions in Ireland were

Artist: John Roberts - A South View on the River Liffey, Dublin, British Library (1807)

"taking credits of [from] our agents in those parts for such of their victualling as was cheapest, and providing the same themselves"12. In March of 1710, the Victualling Board again complained of the problem. This time, it was "the contract[ed beer] brewers giving pursers money in lieu of beer"13. In addition, they complained about "pursers giving receipts for what they have clandestinely disposed of [sold] and never sent on board"14. So the 1701 Instructions had failed to eliminate the problem, being still warned of almost 10 years later. The Board suggested that captains and/or their clerks be required to not only inspect the provisions sent aboard, but that they provide certificates attesting to what was received.

The 1710 Victualling Board letter also identified another purser's cheat. At the end of a voyage, if the purser was in debt to the crown, the purser sold off any provisions which were worth more in the local market than the navy would credit him for upon their return to stores. However, the Board sided with the pursers on this one, suggesting that when a purser was in debt, he shouldn't have to accept a lower rate than the market as a credit on his account.15

None of this appears to have completely solved the problem of the purser illegally selling a ship's supplies, however. In January of 1718, the Navy Board sent a copy of a letter from Abraham Nicksons notifying them that the purser's deputies on ships lying in the harbor at Portsmouth were

Artist: Thomas Rowlandson - Portsmouth Point Caricature (1811)

"continually selling and disposing of his Majesty's beer to the merchant ships and inhabitants of Portsmouth and Gosport".16 What became of this complaint is not indicated.

There were cases where a ship's purser had a justifiable reason to sell the ship's provisions. In the early 1690s, the purser of HMS Chester was accused by some of the ship's men of 'disposing' of the ship's provisions 'to persons other than the ship's company'. It is not clear from the statement whether the victuals were given away or sold, although, based on the purser's statements, they must have been sold. In response to the accusation, the purser wrote the Admiralty that some of

the merchant ships [which were in convoy with the Chester, which acting as their protector] being ready to perish for want, I did supply them with two butts of beer, and when the ship was in Ireland, I victualled her on my own account for 14 days, besides a thousand pieces of beef I bought on my own account, which is the beef the informers allege against me; and likewise have bought of my captain and officers a considerable quantity, which enabled me to do what is here alleged against me, which I suppose to be just and without prejudice to his Majesty's service, especially since the subjoined certificate will demonstrate the ship never to have been in want of provisions or necessaries through my fault or negligence.17

Historian N. A. M. Rodger identifies three other ways a purser might cheat the system. The only one he considers likely to have been used with any regularity is the sale of clothing from the slops

Artist: Samuel Scott

Sailor Smoking, From Shipping at Anchor in the Thames Estuary (mid 18th c.)

chest and tobacco from his supply to men who were no longer on the ship due to death or desertion. After these men were gone, the purser could record a sale of either commodity to them, which was then paid to the purser out of the man's salary at the end of the voyage. This was a double win for the purser; in addition to the payment he received, still had the unsold product. "How common this practice was is difficult to say, since it was and is difficult to detect."18

Rodger dismisses the other two methods as being difficult for a purser to manage. The first involved the purser having good provisions condemned (something requiring the assistance of the surveying team in charge of verifying such claims) and then served, allowing him to credited for their loss and still have them credited to his account because they were recorded as being eaten. He could similarly have victuals which were actually bad condemned and then served anyhow. The difficulty here can be seen on the section on purser's procedures - most bad victuals declared bad were required to be returned at the voyage's end. The second method Rodger suggests involved the purser issuing the men less than their prescribed allowance but claiming they had eaten it, thus stretching out the supply. This would require the complicity of the captain.19

Of this second method, historian Janet MacDonald says, "given the situation of a ship full of dark nooks where aggrieved seamen could lurk with a belaying pin, it is unlikely to have been a general practice. Even without resorting to this sort of thing, the seamen had a mechanism for complaining about food"20. Rodger similarly points out that the men had the right to file a formal complaint about being served bad victuals with navy officials which could lead to an inquiry resulting in the purser's (and potentially the captain's) behavior being discovered.21 Whether such things happened not, several sailors writing during this period do suggest that pursers intentionally shorted them or gave them bad provisions.

1 R.D. Merriman, 'Navy Board to Admiralty - April 23, 1694', The Sergison Papers, (Naval Clerk of Acts), 1950, p. 246; 2 Merriman, The Sergison Papers, p. 238; 3 Commander R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 301; 4 Merriman, 'Navy Board to the Secretary of the Admiralty - June 6, 1698', The Sergison Papers, p. 258; 5 Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, p. 251; 6 Merriman, 'Admiralty to Navy Board - August 21, 1699', The Sergison Papers, p. 259; 7 Merriman, 'Admiralty to Navy Board - January 14, 1700/01', The Sergison Papers, p. 264; 8 Paula K. Watson, "The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714," University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p. 73; 9 Merriman, 'Admiralty to Navy Board - January 14, 1700/01', The Sergison Papers, p. 263-4; 10 Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, p. 253; 11 Merriman, 'Admiralty to Navy Board - January 14, 1700/01', The Sergison Papers, p. 264; 12 Merriman, "Victualling Board to Secretary of the Admiralty, 9th August 1708", Queen Anne's Navy, p. 286; 13,14 Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, p. 298; 15 Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, p. 300; 16 Daniel A Baugh, Naval Administration 1715-1750, 1977, p. 418; 17 Merriman, The Sergison Papers, p. 256-7; 18,19 N. A. M. Rodger, The Wooden World, 1986, p. 95; 20 Janet MacDonald, Feeding Nelsons Navy, 2014, p. 14; 21 Rodger, p. 94-5

Crew Complaints About Navy Pursers

"The purser is claimed to have been the ‘most denounced, satirized and lampooned of all the officers in the King’s ships’; an ‘alchemist’ who could transform rotten and mouldy food into something quite edible' and ‘a dexterous cheat.’" (Karen McBride, Tony Hines and Russell Craig, A rum deal - the purser’s measure and accounting control of materials in the Royal Navy, 1665-1832, 2016, p. 2)

In charge of procuring and overseeing the distribution of the food, selling necessary supplies, slops and tobacco and loaning money to the men against their future pay, the purser was bound to be unpopular with them. Descriptions by historians suggest that pursers were '[s]ocially and psychologically ....isolated, a natural target for the suspicion of his shipmates, the complaints of the ratings [officers] and the oppression of the captain"1. They were "loaded with the maledictions of many generations of seamen, ...already condemned."2 A variety of complaints were directed at the purser,

Artist: Edward Barlow - HMS Augustain, From His Diary

although most of them occurred before the creation of Victualling Committee in 1683. A few are even from before Samuel Pepys' revision of victualling procedures in 1665.

When Edward Barlow was serving on 5th rate Augustine in 1661 he sourly mentioned the 'purser's pound' being taken out of their already reduced short-allowance victuals, adding that the food "always served out to us without scraping, the foul and the clean together, and the rotten with the sound, and mouldy and stinking and all together, and we had Hobson's choice, that or none, and the purser alleged that the waste [for which he was being credited in his 1/8 share] was in the bread and butter and cheese, and that it would not hold out the same weight (as) he had received it at."3 Barlow's convoluted complaint is that the purser's pound allowance was given to him so that the rotten parts of the food could be removed. Then the sailors should receive the full weight of sound food. He says the purser claimed the rotten parts were only found in the bread (biscuit), butter and cheese. However, as historian J. R. Tanner explains, the purser's pound only applied to biscuit, beer, butter, cheese, and pease. "The beef, pork, and fish, not being served by weight, were not susceptible of this treatment"4.

Barlow later complains that the same purser watered the beverage wine (wine diluted with water) three times more than was allowed by the navy. (He was likely either incorrect or exaggerating for effect.) Barlow said the purser "always buyeth the worst [quality wine] and putteth the rest of the money into his own pocket: and if a poor seaman do but speak, then is he in danger of being beaten, for the purser and captain holding together and sharing all the gains that cometh that way, a poor man must not be heard to speak for that which is his right."5 Here we would need complicity between the captain and the purser, which might have occurred if the purser paid the captain part of the ill-gotten gain.

Artist: Edward Barlow - HMS Monck, From His Diary

While aboard the 3rd rate HMS Monck in 1666-7, Barlow again complained that "if we had had our full allowance, we should have had twice as much, but the rest our purser put into his pocket."6 He notes that the purser also owed the men five or six weeks of short allowance money7 (money paid out the purser's funds to the sailors for the periods when six men were served the quantity of food normally given to four). This may not have been unusual for the period, however, given that the navy was having a difficult time paying anyone. Still, the men brought the matter up to Peter Pett, the resident commissioner of the Chatham Dockyard who ordered the purser to pay them. Barlow said their purser gave them half the money they were owed, telling them that that was all he had. He vowed to pay the rest later, which Barlow said he never did.

Barlow was pressed into HMS Yarmouth in May of 1668, where he again complained about the beverage wine, this time saying, "our purser would not go to the price of that which His Majesty allows [to buy wine]

in his ships, for then he could not keep to himself what was our due."8 As a result, the men then bought the slop clothes the purser had for sale so that they could resell them in port towns to obtain money to purchase better alcohol.9 Barlow had previously explained that navy sailors bought "such clothes as they think will yield the most money, setting

Artist: Edward Barlow - HMS Royal Sovereign, From His Diary

their hand to the purser's book to pay at pay-day ten shillings [to the purser] for that which costeth in England seven, and going ashore with it sell it to the Spaniards or to any other people where they are, for four or five shillings, many taking up all their wages in this manner"10.

On Christmas Day of 1668, he goes off on another rant against the purser explaining that "the captain and purser and other officers, having the best of all things, a poor man is not to be heard amongst them, but must be content to take what they will give him, they many times putting that into their pockets which is a poor man's due."11

Barlow's next tour on a navy vessel wasn't until 1691 when he volunteered to sail on the first rate Royal Sovereign. Here, he was placed in the lower officer ranks as a midshipman. This may explain why he only mentions working with the purser12, never complaining about him abusing his position, or trying to steal their money. Of course, the improvement might also have occurred because the Victualling Board had been established, operating under the rules found Victualling Instructions in 1683.

The next series of complaints about a navy ship's purser come from John Baltharpe's poem about the voyage of the HMS Saint David to the Mediterranean. He directs several complaints at the purser about the quality and quantity of the food supplied to the ship in the Fall of 1670.

Artist: Annibale Carracci

Man Weighing A Piece of Meat (late 16th c.)

For want of Victuals, we are now grown faint.

Our Beef, and Pork, is very scant,

I'me sure of weight, one half it want[s]:

Our Bread is black, and Maggets in it crawl,

That's all the fresh Meat, we are fed withal;

When we these things to Sir J[ohn]. Harman [Rear-Admiral] say,

Our Purser mends the matter for a day:

Thinking to make us weary of complaining,

But he upon our Bellies still is gaining.

Old Taylor, he both Calls and Bawls,

Dispatch, make haste, Aloft hammawls.

He is in haste, as if the Spits were turning,

Nay, in such haste, as if the Meat were burning:

But when the work is done, as I'me a sinner,

Foremast-men havenaught but bread for diner13

Baltharpe elsewhere suggests that the purser doesn't give the men their full allowance of victuals, which makes it difficult for them to heal14 and accuses the purser of giving them 'stinking beef' and trying to hide his transgressions by giving them bacon when the ship was at anchor off Livorno, Italy.15 Like Barlow's complaints about the purser, Baltharpe's all occurred before the Victualling Commission was put in place.

The one source of complaints we have about the purser from during the golden age of piracy come from a pamphlet written in 1709, allegedly by cook Barnaby Slush on the fifth rate HMS Lyme. However the name Slush is a pseudonym and it is likely that the author wasn't a cook at all. The Lyme was commissioned for the Mediterranean in January of 1704, spending all her time there until after Slush's book was printed, so if the author was aboard the ship that was where he was stationed. Whoever he was, he spends much of the politically-motivated pamphlet attacking the navy hierarchy and practices, directing one, and perhaps two, comments at the purser.

He first notes that "there are more ways of Pilfering than down-right cutting of [stealing] Purses, so some there are in the Navy, who when they cannot snap at [steal] Provisions by the Lump, Will... exercise their Talents at small Game; thus Ships in the Channel, or in Road-steeds, where Her Majesty allows twice a Week fresh Meat, in lieu of Salt Provisions; some Gentlemen there are found such Humble Sinners, as to cut off the ¼ or at least the 1/8, of this Allowance,

Artist: Dirck Volckertsz Coornhert

Loading Ship, De Deugdzame vrouw verkoopt haar waren (1555)

and ingross it to themselves."16 It is not entirely clear that he is talking about pursers here, although it is either them, the ship's stewards or the victuallers. Since it was the purser's job to bring victuals aboard (with the assistance of his stewards), they are the most likely target of this criticism.

He later levels a direct complaint about the theft of food at the purser, which easily ties in with the above comment. "[Pork and] Peas is a Noble Food... and therefore, and I would not have 'em [the sailors] wrong'd of one ounce of their Three Pound Pieces [of pork], so nor of one single Pea neither, if I could help it. ... [But] if the Purser will deliver me but about half the due Measure [of pork] to Boil, the Fault most certainly lies not at my door."17 This suggests that he believes the pursers were stealing food from the men. Yet it is only one complaint against the purser among several sailor's accounts from the period and it is included in a pamphlet intended to criticize everything the author found objectionable about the navy. This at least hints that the creation of the Victualling Committee benefitted the average sailor.

1 N. A. M. Rodger, The Wooden World, 1986, p. 96; 2 Michael Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, 1896, p. 82; 3 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of His Life at Sea, 1659-1703, 1934, p. 51; 4 J. R. Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy from the Restoration to the Revolution: Part II 1673-1679", The English Historical Review, Vol. XIII (1898), p. 30; 5 Barlow, p. 54; 6 Barlow, p. 127; 7 Barlow, p. 128; 8 Barlow, p. 159; 9 Barlow, p. 160; 10 Barlow, p. 152; 11 Barlow, p. 162; 12 Barlow, p. 479, 480 & 500; 13,14 John Baltharpe, The Straights Voyage, or, St. Davids Poem, 1671, p. 58; 15 Baltharpe, p. 59; 16 Barnaby Slush, The Navy Royal, Or a Sea Cook Turn'd Projector, 1709, p. 32; 17 Slush, p. 77