Organizing Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Next>>

Organization of Ship's Food In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 11

Officers In Charge of Food - Masters and Supercargos

The English navy's policy during the golden age of piracy was to have the masters of small vessels take care of provisioning their ships, apparently not seeing the need for a purser. When food needed to be obtained by merchant ships who had no purser, the task often fell upon the ship's master or, possibly, the supercargo. For privateers during the GAoP, there are two examples of owner's agents being involved in procuring victuals.

Navy Commander as Purser

The navy commander (often colloquially called the captain) was responsible for overseeing the purser. Writing about the conditions in the navy in 1640, William Monson explained that the commander was to "see every man be provided of his diet at a due and seasonable time; and for the better ordering of victuals there are divers officers appointed in sundry rooms [offices]"1. However, on some naval vessels, the commander actually functioned as the purser. During at least part of the golden age of piracy, the master served as purser on English naval vessels with less than seventy men, making him responsible for procuring food and taking responsibility for having it loaded and delivered to the ship.

Artist: Crispijn van de Passe

Loading Ship, Jona in de haven van Joppa, (1574-1637)

As mentioned earlier, the navy decided to assign pursers to sixth rate vessels with more than 70 men during this period, although it isn't certain exactly when this occurred.2 Historian R. D. Merriman predicates this occurred in response to a complaint by an anonymous sailor to the Lords of Admiralty in January, 1697 about "the intolerable abuses that both officers and sailors do receive in all such of his Majesty's ships, where captains act as pursers".3 This was forwarded to the Navy Board, who, in a letter written two days after receiving it, suggested the "allowance of pursers to the 6th-rates of 70 men and upwards may be convenient, as well on those accounts as for easing the commanders of the said business, and giving them more liberty to perform the other part of their duty."4 Merriman didn't find the navy's response to this, although he believes they agreed with it. By way of proof, he points to the 1731 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea which assembles various procedures established in previous decades. In the chart Wages for each Rate, a salary is noted for pursers in all ship rates, including the sixth rates.5

After the end of the GAoP, a memorial sent from the Admiralty to the King on September 29, 1738 discusses the problem of captains of smaller naval vessels serving as pursers. It explains,

Having taken into our consideration the many and great inconveniences arising from the present method of allowing captains of sixth rates and sloops to be pursers, and to have the charge of the provisions belonging to the ship, which in all other rates are committed to the care of a distinct officer, who being under the cheque and comptrol of the captain, both the seamen are better served with their just allowance of provisions and the captains do better perform their duty on the services they are employed; we do therefore humbly propose that a purser be allowed to each of your Majesty's ships of the sixth rate, which was the ancient practice of the navy, and also to all other small ships of sixty men and upwards, with a salary of forty shillings a month and one servant, to be borne as part of the ship's complement and discharged when the ship is put out of commission.6

From this, it appears that sixth rate ships had been assigned pursers 'by ancient practice' (referring, apparently, to whatever occurred following the discussion by the navy hierarchy in 1697). This suggests that some sixth rate ships were assigned pursers before this pronouncement, although whether it was for ships with 70 men or more is not stated.

Most of the available documents related to commanders victualling navy ships come from the records of complaints made about them and what the Navy Board attempted to do to prevent the captains from cheating the system.

Artist: Nicolas Ozanne

The Port of Rochefort, Seen from the Colonies

Store (1776)

As a result, the information available focuses primarily on how the navy commanders circumvented the system with regard to provisioning. No doubt there were commanders who followed the rules and managed the role of purser as well as they could given that it was just one of many things they had to do shipboard, but the records contain little information about them.

One example of cheating comes from a letter the Victualling Board wrote in July of 1708. "Captain Rogers, commander and purser of her Majesty's ship Seaford... having indented for a month's provisions only [in Dublin, Ireland], yet has taken credit for all the pork and above half the beef, those species being cheapest in that country."7 The Seaford was a sixth rate ship8, apparently small enough that the captain served as its purser.

Like the purser, a commander in charge of overseeing victualling incurred a charge against his salary for the cost of victuals loaded on his ship. To get the charge removed, he was required to either show the victuals were eaten (by recording who ate what and how much they ate) or return what was not consumed for a credit. He could also sell the excess at the end of the voyage if the local market rate was higher than the charge against him. In addition, when he could purchase victuals cheaper than the navy-established rate for that type of food, his salary would be credited at the navy rate for the consumed victuals, allowing him to profit on the difference between the market rate and the navy rate. So Captain Rogers' might have received money from the contractor for the beef and pork he didn't take at the navy's contracted rate allowing him to turn around and purchase it at the local, cheaper market rate and pocket the difference.

Several examples of the 'commander as purser' cheating come from the anonymous petition sent to the Lords of Admiralty in 1697. There, the author complains that his captain does not supply them with an adequate number of candles, one of a number of 'expendable items' he was required to supply, paid for out of his own pocket. The captain/purser could set the rate he charged for such things. However, not having to supply the candles saved him the trouble and expense of buying them in the first place.

The anonymous author levels several other accusations against commanders acting as pursers. These included "receiving bribes of victuallers... [allowing them to] frequently receive such victuals on board as is not eatable and have been denied [refused] or put on shore from other ships."9 He notes that such commanders add men to the ship's roster or indicate that men who have left the ship prematurely remained on board longer than they really did, allowing them to charge the navy for victuals never consumed, "thereby making [those sailors] victuals their own."10 The author also blames the commander for 'often' putting the sailors on short rations (six men being fed the amount normally given to four men), another tactic which would allow him to conserve food and later return or sell it. In this scenario, he would falsely report regular rations being served while actually short rationing the men.

None of these anonymous accusations were new to the profession; all are found in one form or another in the section on cheating by pursers. However, much of this cheating by pursers had been reduced before the golden age of piracy by having the commander oversee several aspects of the the purser's job, giving him final approval on the purser's reports and lading. When the commander was the purser, however, no such controls were in place, creating great potential for cheating.

Port Royal and Kingston Harbour (1782)

As late as June of 1715, the Victualling Board complained that naval victualling

in the West Indies and other foreign parts where there has not been any Agents or correspondents to this office the same appears to have been attended with very irregular proceedings, by the commanders frequently taking upon themselves the sole management of the providing provisions for victualling their respective ships, whereby the advantage to the Crown from their being cheques [limitations] on the pursers (whose proper business it was) has been entirely lost11

Here, the commanders of larger vessels stationed overseas may have taken on the purser's role so they could cheat in the same ways the 'captains as pursers' did. Even when the purser arranged for victualling, the commander sometimes worked with him to profit by the navy's system.12 The Board complained of "many extraordinary charges introduced, which were not known in the victualling till of late years"13. These included renting storehouses for victuals while stationed at a foreign port, sometimes even two of them in different locations, renting boats to move things from ship to shore and expenses for unneeded casks and bags.

Although Victualling Board does not explicitly state their suspicions, such activities hint at the buying of unnecessary provisions. They could either pay the victuallers using bills of exchange drawn on the Board or by being reimbursed for their outlay.14 "All that was required was to state that more articles had been bought than was the case, or to declare a higher price than that which had really been negotiated, in order to make a substantial profit."15 They could also buy substandard provisions at a discount and report paying full price.16

In order to prevent such things, the Victualling Board established 'better regulations' in June of 1715, several of were mentioned previously. They included: 1) requiring ships sailing to foreign ports to take the full eight months of provisions with them rather than a partial shipment along with vouchers and payments for the balance, 2) putting the men on short rations after leaving England to extend their provisions, 3) obtaining only overseas provisions from navy victualling agents or contractors

Artist: John Carwitham - Fort George, New York City (c. 1736)

with whom they had arranged pricing and 4) having pursers make all the victualling arrangements where there were no such agents or contractors, 5) prohibiting the hiring of boats to transport provisions and 6) using great care in stowing and removing provisions in the hold to prevent unnecessary damage.17

Five months later, the Victualling Board wrote that in examining the accounts of ships captains who had victualled their own ship that this should only occur "in cases of absolute necessity" because it gave the commander too much control over the ship's victuals, particularly since the men could only complain to the captain about the quality or quantity of victuals. As a result, the Board said, "We have therefore made contracts for supplying such of his Majesty's ships as may be in want of provisions not only at New York, but at Barbados, the Leeward Islands, New England, Virginia and Maryland"18. The naval commanders did not give up their illicit profits quietly, however. "A seven-year struggle ensued, and only after repeated Admiralty orders did the new policy become established."19

In October of 1716, the Victualling Board complained to the Admiralty Secretary that "the commanders find so many ways to evade complying with our agreements [with the contracted victuallers], and lay our contractors under such difficulties, that unless examples are made of some of them, we fear the stopping [of] their accounts will not be sufficient"20. The difficulty for overseas victuallers who contracted with the navy came from their agreements to supply a certain amount of ready provisions at the navy-specified price. When commanders purchased their supplies from non-contracted victuallers, the contracted victualers who had to keep supplies on hand per their contract wound up with rotting food.

For example, Virginia victualler Charles Chiswell wrote that he expected to victual three sixth rate navy vessels stationed there - the Shoreham, Success and Valeur. He had purchased three months provisions for the Shoreham, four months for the Success and six for the Valeur. His letter complained, "I have been at considerable expense in collecting a complete victualling of all species into one warehouse…

Artist: Dominic Serre - A Sixth Rate Frigate (18th c.)

I find the orders of the Commissioners of the Victualling, nay even of the Lords of the Admiralty, are to be evaded and not regarded. I have had twenty months provisions for 100 men by me near nine months, and have had only a demand for six weeks by the captain of the Shoreham."21 He went on, explaining that HMS Valeur captain John St. Loe told him that

his ship was victualled for four months, except butter and cheese (things of near double the value we have for them) [the local market price was double the price allowed by the navy contract], of which he demanded about 700 pounds of cheese and 280 pounds of butter… I then showed him my bread, which he allowed to be good but did not want, though his men told me there was not 100 pounds in the ship, at which they were ready to mutiny; but New York he takes [stops at] in his way home, and that is a cheaper market for bread.22

Eventually, through repeated threats and letters demanding that ship's commanders get their victuals from the sanctioned victualling contractors, this behavior slowed and eventually ceased, although not until near the end of the golden age of piracy. As late as December 21, 1722, victualler John Caswall in New York wrote that ship's commanders "too ...demand only broken proportions, and in such case only of those species that are scarce and dear, at the same time supplying themselves with those that are cheap from other hands, which is ...very often a very heavy loss to the contractor, who is obliged to have a large stock on hand to answer any demand upon him."23

Rather than leave this part of the article with the idea that the only time a naval commander was interested in victualling his

Artist: Willem van de Velde the Younger - Charles Galley (1677)

vessel was when he could cheating the system, we have something from Jeremy Roch's journal upon assuming command of the fifth rate Charles Galley in 1689:

I had my commission for the Charles Galley by the third of April following, with orders to go down to Plymouth to fetch up men to man her. Upon which I sold my horse and presently took Post and [sailed] away for Plymouth, where, in a week's time, I got near 200 men and hired a ship and victualled her on my own account, put all my men aboard and carried them all safe into the river of Chatham, where the Galley then lay, and entered them all on board her by the 24th of April, so that I manned her and got her ready to sail in less than three weeks.24

Finally, navy ship commanders could get involved in victualling their vessel in another way. The 1731 navy Regulations stated that "any Prizes ...taken from an Enemy in Foreign Parts [when] it shall be judged necessary by the Commander in Chief to supply the Wants of His Majesty's Ships out of their Provisions, the same shall be first regularly surveyed, and such Quantities thereof as shall be found good in their Kind, may be issued to the Pursers, and they be charged therewith."25 Admittedly, the commander's role in with regard to food was limited in this situation. The regulation went on to declare that if there were navy purchased provisions aboard the ship, they had to be served before anything else retrieved from a prize ship.

1 William Monson, The Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson, Vol. IV, M. Oppenheim, ed., 1913, p. 64; 2 The Sergison Papers, R. D. Merriman, ed., 1950, p. 238; 3 Sergison Papers, p. 253; 4 Sergison Papers, p. 254; 5 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea,1st ed, 1731, p. 144; 6 Daniel A Baugh, Naval Administration 1715-1750, 1977, p. 70; 7 Merriman, "Victualling Board to Secretary of the Admiralty, 9th August 1708", Queen Anne's Navy, p. 286; 8 'British Sixth Rate frigate 'Seaford' (1697)', threedecks.org, gathered 6/4/21; 9,10 Sergison Papers, p. 253; 11 Baugh, "Victualling Board to Admiralty Secretary - 22 February 1714/5", p. 409; 12 Christian Buchet, The British Navy, Economy and Scoiety in the Seven Years War, 1999, p. 20; 13 Baugh, "Victualling Board to Admiralty Secretary - 22 February 1714/5", Administration, 1715-1750, p. 409; 14 Douglas Hamilton, "Private enterprise and public service Naval contracting in the Caribbean 1720-50", Journal for Maritime Research, 2004, p. 38; 15 Buchet, p. 20; 16 Daniel A Baugh, Naval Administration in the Age of Walpole, 1965, p. 393; 17 Baugh, "Victualling Board to Admiralty Secretary - 22 February 1714/5", Administration, 1715-1750, p. 410; 18 Baugh, "Victualling Board to Admiralty Secretary - 12 November 1715", Administration, 1715-1750, p. 413; 19 Baugh, Administration, 1715-1750, p. 402; 20 Baugh, "Victualling Board to Admiralty Secretary - 22 October 1716, Administration, 1715-1750, p. 415; 21,22 Baugh, "Victualling Board to Admiralty Secretary - 22 October 1716, Administration, 1715-1750, p. 416; 23 Baugh, "John Caswall, Contractor for Victualling his Majesty's Ships at New York, to Victualling Board - 15 December 1722", Administration, 1715-1750, p. 429; 24 Jeremy Roch, "The Fourth Journal of Jeremy Roch", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, Bruce Ingram, ed., 1936, p. 112; 25 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea,1st ed, 1731, p. 67

Non-Naval Ship's Masters as Purser

On smaller commercial vessels, many of which had no purser, the masters victualled their vessel overseas. At times, they victualled the ship upon leaving their home port when there no managing owner/ship's husband responsible for this.

Artist: Nicolas Ozanne

Lading a Small Ship, The Port of Landerneau seen from Saint Julien (18th c.)

Outside of the large merchant companies and some slaving vessels, the average number of men assigned to merchant ships gradually declined (as determined by the average men employed per merchant ship tons burden).1 This meant less food was required on a ship and the need to track of victualling was reduced. (This is provided merchant captains bothered to keep track of what the men ate at all.) All of this made it easier for the master to assume this task.

Another factor contributing to the master's ability to handle victualling was that "the business and clerical work [the purser] had done was absorbed by increasingly literate masters, aided by agents ashore."2 So both the amount of reading and math needed to determine the amount of food required decreased and the master's abilities increased. He could make this determination particularly when working with the ship owner's agents at both the departure and arrival ports. Many successful ship's managing owners sailed to the same destination port repeatedly, allowing them to develop relationships with a local agent who could make sure they got the best prices for incoming goods and were able to fill their ship with the best outgoing goods for the return trip.3

There are a few examples of merchant ship's masters victualling their vessels in the period texts under study. In sailor Edward Barlow's journal, he mentions that in 1675 the 130 ton merchant ship Fflorentine's "master not having victualled his ship at London, intending to have victualled in Scotland for cheapness, but here at 'Kingsaile' [Ireland] we could have it as cheap as at Scotland, so our master agreed with a butcher to kill us meat for eleven shillings the hundred, and there we salted our sea store, for it is a place where provisions are commonly very cheap"4.

Davis reprints ship master Charles Johnson's account of the Cadiz Merchant when she stopped at Livorno in January

Artist: Edward Barlow- Cadiz Merchant, From Barlow's Journal (c. 1680)

of 1679. Among the items listed were provisions including 'beveridge wyne', 'fresh meate', '60 pound of candles' and 'Cabidges sallets and greene herbes'.5 These are all items a purser would be responsible for purchasing when a ship had had one. Since they are included on Johnson's account, the ship's master was clearly serving in this role. He also managed the freight on the voyage, something a supercargo or (at times) a purser might arrange. (Coincidentally, Barlow joined the Cadiz Merchant as second mate in April of 1680.6)

Another example of a master getting involved in negotiating for victuals is found in a story told by sailor Alexander Hamilton. In 1684, the interloping ship Merchant's Delight ran aground on Masirah Island in the Arabian Sea. Captain (and supercargo) Edward Say made a deal with the local Jenebeh tribe to rescue the ship's cargo and sustain the crew for which he agreed to give them half the cargo.7 The tribesmen retrieved the cargo, divided it in half and gave the crew their choice of which half they wanted. They then "treated the English with excellent Mutton, both of Sheep and Goat, and laid in Provision for their Passage to Muskat [Muscat], free of Charge to the Supercargo."8 The Jenebeh even shipped the crew's half of the cargo to Muscat for them.

There are also accounts where buccaneer and pirate masters appear to have been responsible for

Henry Morgan Destroys the Fleet at Maracaibo, From The Bucainers of America (1678)

victualling their ship, although it is impossible to say with certainty from the text that for sure; these may just be cases where the description of the victualling process makes it appear to have been part of the commander's role while other men actually handled it.

While at Maracaibo in 1668, buccaneer Henry Morgan demanded that the Spanish send him "thirty thousand Pieces of Eight, and five hundred Beeves, to the intent his Fleet might be well victualled with flesh. This ransom being paid, he promised in such case he would give no farther trouble unto the prisoners, nor cause any ruine or damage unto the Town."9 Similarly, from the pirate accounts, Pirate Samuel Burgess took the ship he was commanding for merchant Frederick Philipse to Mathelage [modern Mahajanga], Madagascar where Johnson says "he victualled and traded".10

1 Peter Earle offers an excellent summary of this, chalking the decreases in crew size up to increases in ship size, some ship design improvements and less need for men to protect the ship. See Earle, Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775, 1998, pp. 7-8; 2 Ralph Davis, The Rise of the English Shipping Industry in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, 1962, p. 112; 3 Davis, pp. 90, 98-9, 129 & 197; 4 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of His Life at Sea, 1934, p. 265; 5 Alexander Hamilton, A new account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 57 & Colonel Samuel Barret Miles, The Countries and Tribes of the Persian Gulf, 1919, p. 217; 6 Davis, p. 352; 6 Barlow, p. 556; 7,8 Hamilton, p. 58; 9 Alexandre Exquemelin, Bucaniers of America, 1684, p. 144; 10 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 507

Supercargo as Purser

Historian Ed Fox says that on some merchant ships, "the role of the naval purser was often fulfilled by the merchant supercargo, whose duties included marine accountancy."1 Supercargoes represented the people who were transporting the cargo on the ship. Their primary responsibility was to arrange for the sale of the ship's cargo when it arrived at an overseas port and arrange for the purchase of new cargo for delivery and sale at the next port. If the cargo owners were responsible for the victualling of the ship's crew, the supercargo's negotiating skills combined with his focus on representing the owners interests made them a good choice for purchasing food while overseas. Still, none of the accounts under study state that a supercargo specifically assumed this duty. There are some examples of supercargos being involved in food purchasing decisions around this time, however.

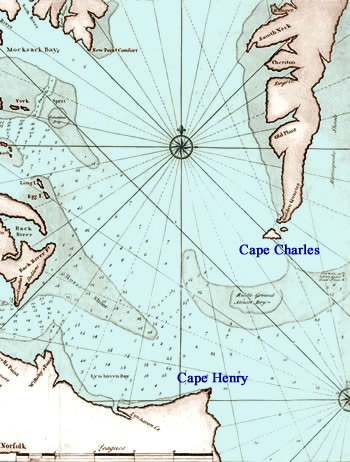

Cartographer: Mark Tiddeman

The Virginia Capes, From A Draught of Virginia (1742)

In April of 1673, sailor Edward Bant testified that the ketch [Little] Barkley was sailing off the Virginia Capes when she spotted a fly boat named Providence. The crew of the Barkley was in need of provisions, so they asked the men on the Providence if they could spare any. "[T]hey answered us if we would hoise out our Boate and come on boarde, they would spare us water and other provitions what they could. in order thereunto wee did soe, and I being desired by the Master and Merchant [supercargo] to goe on board with the Boate to Endeavor to gett what provitions I could"2. Bant, the master and the supercargo took the boat with several other sailors to the Providence, where they discovered that she had been taken by Dutch privateers. The Dutch then sent the boat back to the Barkley with her supercargo and three Dutch sailors. The privateers sent a hogshead (cask) of biscuit to the ketch, although they intended to take everything of value out of her. However, the Barkley overpowered the Dutch sailors and sailed away. The prisoners on the Providence also managed to overpower their Dutch captors and retake that vessel as well. So the supercargo and master were both involved in securing victuals in this case.

As mentioned, William Dampier's privateer crew on the St. George decided in 1705 to split the company so that some of them could sail for the East Indies while the rest remained on the west coast of Central and South America. Here, the owner's agent (equivalent to a supercargo on a merchant ship) divided the provisions aboard the St. George between the two crews.3 This is probably the best example of a specific supercargo being involved in doling out provisions during this period from the sailor's accounts.

Woodes Rodgers' privateer voyage had several men who basically functioned as supercargos on the four ships

Batavia in 1605-1608 (Drawn Between 1675-1725)

which reached Batavia [modern Jakart, Indonesia] in 1710. Edward Cooke explains that it was decided at a committee meeting held on June 3rd: "Mr. [Carlton] Vanbrug[h] [was] to continue [owner's] Agent of the Duke, Mr. [James] Goodall of the Dutchess, Mr. [John] Vigor[s] constituted Agent of the Batchelor, and Mr. Parker of the Marquis, to keep Account of all Things aboard each Ship, and take Care of the general Interest."4 This could be taken to indicate that they were responsible for keeping track of the victuals consumed shipboard, particularly since their supply was considered by the committee that preceded them. Historian Ian Abbey explains, "These men cooperated with the [expedition's] Council [of the officers, shipboard owners and owner's representatives] in taking stock of all plunder and completing mundane transactions with the Dutch in Batavia."In addition, they bartered cloth from the captured cargos 'to help pay for supplies.'"5 However, is it not mentioned whether these agents had anything else to do with buying or keeping track of the victuals.

1 Ed Fox, "Piratical Schemes and Contracts", University of Exeter Thesis, 2013, p. 103; 2 "35. Declaration of Edward Bant and Others. May 8, 1673", Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period - Illustrative Documents, John Franklin Jameson, ed., 1923, p. 62; 3 William Funnell, Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 86; 4 Edward Cooke, Voyage to the South Seas, Vol. 2, 1712, p. 58; 5 Ian I. Abbey, "Raiding And Trading Along The Spanish Lake: The Woodes Rogers Expedition Of 1708-1711", Doctoral Thesis, Texas A&M University, 2017, p. 253