Organizing Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Next>>

Organization of Ship's Food In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 10

Officers In Charge of Food - Ship Pursers, Continued

Pursers on Merchant Ships

Pursers had a role on some merchant ships. They were typically employed on large, well-organized, sailing ventures such as the merchant vessels of the East India Company (EIC), the Royal African Company and the Levant Company of Turkey Merchants. They were also "often found in the middle decades of the seventeenth century in Mediterranean and American traders, [although they] had nearly disappeared by 1700"1.

There is some evidence for pursers on smaller merchant ships during the Golden Age of Piracy (GAoP) as well.

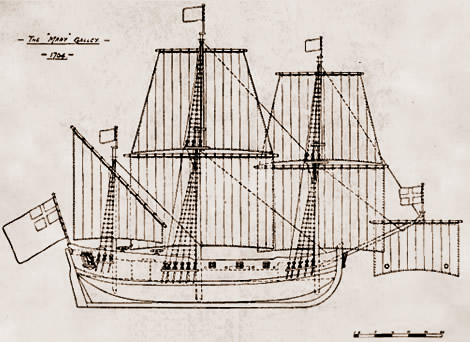

Mary Galley Sail Plan, From The Papers of Thomas Bowrey 1669-1713 (1704)

For example, the 167 ton merchant vessel Mary Galley which made several voyages in the East Indies between 1704 and 1707 had a purser. The records of Thomas Bowrey, who served as the managing owner (aka ship's husband), include a reference to an indenture between him and his fellow owners (Thomas Hammond and George Jackson) and purser Elias Grist. "Grist paid £53. 15s. before it was sealed, apparently by way of guarantee, and was to receive 1/2 per cent. of the homeward cargo sold."2 Grist's payment may have been a guarantee, although it might also have been payment for the opportunities presented by the position, something discussed previously in the section on navy pursers. Of Grist, the Bowrey papers editor Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Carnac Temples opines that he is not presented "in a favourable light... and... when trouble came upon the captain and the ship from the French privateers, he shows himself to have been of a grasping and unscrupulous character and capable of despicable actions."3

The purser's job on merchant ships would be similar to that of the naval pursers. Of the various accounts which mention them, the most detailed were those established by the East India Trading Company (EIC) in 1621. It is not clear that these rules were still in place for EIC ships during the golden age of piracy seventy years later. However, they are generic enough that many, if not all of them, could easily have in use on a variety of merchant vessels during the GAoP.

As already noted, the Husband was responsible for buying food at the beginning of the voyage for EIC vessels. When they were EIC owned ships, it was the Company's Husband's responsibility; when they were leased (post-1657), it appears to have been the Ship's Husband's responsibility with some of the supplies being provided by the Company. The Company originally supplied victuals from the

Artist: Jacob Peeters - Surat (1690)

EIC's London Warehouses in the Deptford dockyard on the Thames. In the early voyages of company-owned ships, the whole victualling allotment required for a voyage to the East Indies and back was loaded before leaving London. As a result, "ships bound for Bantam were provisioned for two years and those for Surat for eighteen months."4 Over time, the East India Company set up provisioning locations along the route to the East Indies and "[b]y the mid-eighteenth century owners' instructions to commanders stated that seven months' provisions [loaded upon leaving England] should be sufficient for a voyage."5

This was not always the case for non-EIC vessels. From correspondence concerning the East Indies-bound Mary Galley between managing owner Bowrey and the ship's master Edward Tolsen, supercargo Elias Dupuy and the ship's chief mate, it appears that either the purser or the master were involved in procuring the initial supply of victuals at Gravesend. Bowrey's records for the voyage include an extensive list of provisions purchased on September 3rd, 1704 for a thirty man crew for 2 years. In the letter, Bowrey complains that although captain Tolson is expected to have his food supplied from the ship's common provisions, he learned that the victualling arrangements included "a whole Sheepe and a Shoulder of Veale at Gravesend, and by Agreement with the Butcher sett it downe as Beefe.... I hope we shall have no more such doings of setting down one thing in the Name of another."6 Since it benefitted the ship's master and those who ate at his table, one of the officers clearly had input to the victuals supplied.

Artist: Thomas Rowlandson - Market Harborough (late 18th/early 19th c.)

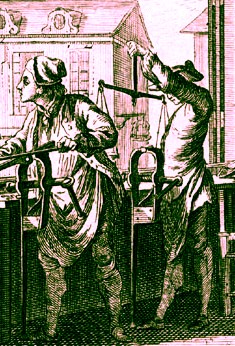

Even though they didn't initially purchase food, EIC pursers did have several duties related to victualling the ship during this period. In advance of the voyage, they were "to take a true accompt of all the Harborough victuals [fresh victuals from Haborough Market], and victuals for the Voyage [dried and salt victuals], Provisions, Stores, and Merchandize, of whatsoever kinde"7. Either the purser or his mate were responsible for making certain what they got from the Deptford warehouses was correct. They were to "check the waight of the Bisket, Flower and Meale from the Baker for the voyage"8, issuing a receipt to him for what they got. They were also to employ "a [Balance] Beame and Scales, to receive, and note downe the waight of Cheese, Butter, Bread, Brasse, Copper and Pewter vessels, or any other things which are charged to the Company by waight."9 The pursers were most likely still responsible for these tasks when the ship's husband took over food purchasing after the company converted to the leasing model.

During the voyage, the EIC had several provision-related obligations as well. Similar to their naval counterparts, EIC pursers were responsible for monitoring the food supply during a voyage. The 1621 Instructions only mention that they, along with the other ship's officers, were to keep track of the "daily expending of all the said stores and victuals, to the end that at all times it may be knowne what provisions remaine in the Ships."10 Unlike the navy's instructions, the EIC's do not mention monitoring how much food each sailor ate. This may have changed later.

Balancier, From The Encyclopedia of Diderot &

d'Alembert, Vol 2 (1765)

Pursers were also to report to

the Governour [of the East India Company], Deputy, and Committees by their Letters, from the Cape of Good Hope, or from any other place, where they shall have opertunitie to write, concerning the goodness or defects, of the beefe, porke, bisket, Wine, beere, Sider, Cordage, powder, or any other provisions whatsoever; and also concerning any want, which shall be found in the number of peeces of beefe and porke, in any of the Caske differing from their packing here, or any want of waight in the said peeces of beefe and porke, or powder, or the like, which advices they shall send, testified and under-written by the Master, or some other principall Officers of the ship.11

This was likely that this one was included in the EIC purser's duties after the company switched to the leasing model in 1657 and possibly for pursers for the Royal African and Levant Companies.

In addition to the already mentioned independent merchant vessel Mary, there are a couple of examples of pursers found in the sailor's accounts from this period.

Most of the available information about the (initially) monopolistic Royal African Company (RAC) concerns their transportation of slaves from Africa to the West Indies (although that was not their sole business) as well as their various political and corporate intrigues.

Royal African Company Arms, From The livery companies

of the City of

London, By William Hazlitt (1892)

The Company both leased and licensed ships to trade in Africa up until they lost their monopoly in 1689, although they continued to operate for decades after that.12 They probably had some standing policies about the makeup of their crews, even if they were only by custom. Interestingly, the RAC got at least some of their provisions from the Royal Navy during the golden age of piracy, which would preclude a purser from having to obtain the first outgoing victuals for a voyage.

The sole evidence related to the use of a purser in the RAC comes from the 450 ton slaving ship Hannibal which was purchased by a consortium of owners. She was leased to the RAC for a slaving voyage from England to Africa to Barbados between 1693 and 1694. Master Thomas Phillips kept a journal of the voyage in which he mentions the ship's purser several times13. Unfortunately, he never provides any information about purser's duties, much less the details of provisioning. While it is impossible to extrapolate evidence of widespread employment of pursers on RAC ships from this one instance, it is likely that most RAC leased vessels had them. They were manned more heavily than other (non-EIC) merchant vessels during the GAoP14 and they needed not only to provision their crews, but to provide provisions for the slaves they took aboard when they reached the African coast. William Snelgrave also mentions that he served as a purser on the slaver Eagle Galley which purchased slaves on the west coast of Africa in 1704, although it is not stated that this was an RAC vessel.15 Since he says they only had ten sailors aboard,16 it is unlikely to have been an RAC voyage.

Another merchant company, the Levant Company of Turkey Merchants, was first chartered in 1592 with the merger of the Levant Company and the Turkey Company. Its purpose was to trade and form political alliances with the Ottoman Empire, operating from its founding until well after the end of the golden age of piracy. Their structure and operation had several things in common with

Merchants of the Levant Arms, From The livery companies of the City of

London,

By William Hazlitt (1892)

the the EIC. The Levant company only owned ships in the beginning years of the company, eventually changing to a leasing model like the EIC. One of their officers was a company Husband, although his duty was "to keep the papers, bonds and seals of the company, as well as to pass the Bills of entry for goods on Ships."17 Nothing is mentioned about his being involved in provisioning vessels. The ships the Levant Company hired were between 250 and 600 tons with crews of about 35 to 100 men18, fairly well manned when compared to many independent vessels.

Among other things, Levant Company pursers were responsible for keeping track of and verifying the cargo quantities, numbers and shipper names and swearing an oath to this when the ship reached its first destination port, and, after lading cargo, upon leaving Turkey.19 The Company took responsibility for stocking the ship with food at the beginning of a voyage, adding "the expenses of porterage [transport], loading, victualling, and manning of ships, and the customs house fees" in London to the price of their shipping.20 It is not stated who arranged the purchase of these provisions, although it seems likely that the purser was given this job. In his account of a voyage to the Levant aboard the London Merchant, chaplain John Covel mentions in passing that the ship's "Purser... went a shore and bought all the provisions which we wanted, and with them good store of white Muscadine, a rich, sweet, heavy wine."21 From this, we know the purser was at least responsible for purchasing victuals when the ship stopped en route. He was almost certainly responsible for keeping track of the food on the ship like the naval pursers.

Some slave ships sailed to Madagascar during the golden age of piracy because they were cheaper to buy there than on the west coast of Africa. Like their RAC counterparts, some employed pursers. Following the mutiny aboard the Beckford Galley (a 200 ton slave-ship) off the coast of Madagascar in January, 1699, the galley's purser, "Andrew Somerville, managed to escape and make his way to Mayotta. There he

Ships at Mayotte, From Le Magasin pittoresque (1856)

found an old friend, the Purser of the Ruby [Benjamin Preston], who was trying to save the Company's treasure which had been on board when she was wrecked" in September of 1699 on Mayotte.22 Another account of the Beckford Galley mutiny says that Somerville didn't so much escape as he was let go, being given a boat by the mutineers, with 'about a dozen men' who refused to join the nascent pirates.23 The Ruby was a navy-captured 400 ton 5th rate French privateer which had been purchased and refitted by a consortium of owners in 1698.24 With the help of the Beckford Galley's men, the Ruby's sailors recovered 62,000 dollars from the wreck. This they brought to 'Patta' (probably Pate Island), Africa, arriving on March 30, 1700.25

The 450 ton Speaker, captained by Thomas Eastlake26, was on the coast of Madagascar hoping to slave when she was captured by pirates George Booth and John Bowen in 1699. In the description of events leading up to the capture, it is explained that Eastlake "sent his Purser ashore, to go up the Country to the King, who lived about 24 Miles from the Coast, to carry a couple of small Arms inlaid with Gold, a couple of Brass Blunderbusses, and a Pair of Pistols, as Presents, and to require [request] Trade."27 The purser was captured by one of the pirates and threatened, but they eventually decided to escort him to the native King where he arranged for trade between the Malagasy natives and the Speaker. (This was before the pirates took the ship, of course.)

1 Ralph Davis, The Rise of the English Shipping Industry in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, 1962, p. 112; 2 Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey 1669-1713, 1927, p. 185; 3 Bowrey, p. 122; 4,5 Jean Sutton, Lords of the East, 1981, p. 96; 6 Bowrey, p. 205; 7,8 East India Company (EIC), The lawes or standing orders, 1621, p. 46; 9,10 EIC, p. 47; 11 EIC, p. 47; 12 Historian Kenneth Morgan explains: "The Royal African Company probably accounted for around two-thirds of the British slave trade between 1672 and 1689 and for a half in the 1690s; the remaining portion of the trade was in non-company vessels. Between 1662 and 1713, when the Royal African Company delivered at least 125,000 slaves to British America, less than half of all English slaving vessels in the Atlantic were company ships. Some of the private vessels were ships operating with licences to trade from tl1e Royal African Company (a resort to the need to raise capital)." (Morgan, "Introduction", The British Transatlantic Slave Trade, Vol. 2, 2003, p. xv; 13 Thomas Phillips, A Journal of a Voyage Made in the Hannibal, 1694, p. 184, 196, 214, 216 & 222; 14 Historian Kenneth Gordon Davies states in his book The Royal African Company says that "a voyage to West Africa and the West Indies called for ships and crews above the size commonly engaged in European waters" (Davies, p. 185), noting that crew sizes increased during war, offering an example of the 320 Ton Falconbergh "manned by a crew of 65 in war and 50 in peace" (Davies, p. 189); 15 William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea, 1734, p. 164; 16 Snelgrave, p. 165; 17 Mortimer Epstein, The Early History Of The Levant Company, 1908, p. 68; 18 Alfred C. Wood, A History of the Levant Company, 1964, p. 210; 19 Wood, p. 213; 20 Wood, p. 252; 21 John Covel, 'Dr. Covel's Diary', Early Voyages in the Levant, 1893, p. 143; 22 Charles S. Hill, "Notes on Piracy in Eastern Waters", The Indian Antiquary, November, 1927, p. 125; 23 Charles Grey, Pirates of the Eastern Seas, 1618-1723, 2001, p. 185; 24 Rowan Hackman, Ships of the East India Company, 2001, p. 42 & Grey, p. 186; 25 Grey, p. 186; 26 Daniel Defoe [Captain Charles Johnson], The General History of the Pirates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., pp. 476 & 689; 27 Defoe (Johnson), p. 476-7

Pursers on Privateering Ships in the GAoP

Pursers could also be found in privateering voyages during this period, although there are only three such voyages under consideration here. These include: 1) William Dampier's voyage to the South Seas in the 260 ton St. George (120 men) accompanied by the 90 ton Cinque Ports (63 men) between 1703 and 17051, 2) Woodes Rogers voyage around South America and home via the East Indies in the 320 ton Duke (117 men) and 260 ton Dutchess (108 men) in the years 1708-1711, and 3) The voyage of John Clipperton's 350 ton Success and George Shelvocke's 200 ton Speedwell2 (106 men) along a route similar to Rogers' during the years 1719-1722.

Artist: Thomas Murray - William Dampier (c. 1697-8)

Dampier's privateers appear to have had no purser. The St. George was initially "very well victualled for nine Months" at Kinsale, Ireland before proceeding voyage according to account author William Funnell.3 Their consort Cinque Ports "was

also very well victualled and provided for the said Voyage."4 Who had arranged for the provisioning of the ships at Kinsale is not mentioned. The captain of the Cinque Ports, Thomas Stradling, decided to leave the St. George in 1704 and another disagreement resulted in some of Dampier's crew of the St. George leaving with first mate John Clipperton in a 10 ton prize barque.5 On January 26, 1705, the remaining crew decided to split again - one group intending to sail to the East Indies in a captured 80 ton barque with the rest remaining on the west coast of South and Central America in the St. George. Funnell reports, "And the same day; the Provisions being equally parted according to the directions of the Owners Agent; and four great Guns, with some small Arms, Powder and Shot, &c. being taken out for us; we, (that is, 33 of us who resolved to go in the Bark for India.) went on shore in order to water our Vessel for the said Voyage."6 From this, it appears that the owner's agent (often referred to as the supercargo on merchant vessels) had to take charge of the provisions, probably because there was no purser.

For Rogers' voyage, historian Ian Abbey states that John Finch was the Duke's 'purser and steward'7, but Rogers only refers to him as a steward.8 In his account of the voyage, Edward Cooke similarly mentions that Dennis Reading was the Batchelor's steward, without indicating that he served as a purser.9 A steward could fulfil many of the purser's duties as we shall see, although they were generally subordinate to the purser of a ship and not typically tasked with arranging for the purchase of food on land.

A great deal of sea provision had been loaded on the Duke and Dutchess at the outset, so much that Rodgers complained that their ships' "Holds are full of Provisions ...so that we are very much crouded and pester'd Ships, not fit to engage an Enemy, with out throwing Provision and Stores over-board."10

Duke and Dutchess, From A New Universal Collection of Voyages and Travels,

By

Edward Cavendish

Drake (1769)

When they reached South America - enemy territory - their food was procured from uninhabited sites, stolen from enemy cities, or bartered for or purchased from willing natives.11 To facilitate this, Rogers sent their translator ('linguist') along with a captured native to arrange things.12 "Our Linguist and Prisoner manage their Business beyond Expectation, selling very ordinary Bays [coarse wool cloth] at 1 Piece of Eight and half per Yard, and other things in proportion, so that we have Provisions very cheap."13 Upon reaching Dutch Batavia, the Duke's First Lieutenant Charles Pope went "ashore, [to] send Provisions for all the Ships, and keep a Book of the whole, and send it as early as possible, in a Country-Boat, not above nor under 350 Pounds every other Day, or as often as he could conveniently"14. Based upon the men who are recorded as purchasing victuals, the voyage didn't have an official shipboard purser.

So far, this has been a proof of pursers not being found on aboard GAoP era privateers. However, the last privateering voyage - with Captains Clipperton and Shelvocke - definitely features pursers, although it adds little to our knowledge of a just what a privateer's purser did. Shelvocke does note at the beginning of the journey, the Speedwell was "crouded with provisions for so long a voyage"15 like Rodgers. He adds "that as we were incumber'd only with provisions, we should in a little time eat and drink her into a better trim"16

The Speedwell, From A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great

South Sea,

By George Shelvocke (1726). He further explains that they got "a little fresh provision" at Santiago, Cape Verde Islands in April, 171917 and "60 cheeses, and 300/. of butter, to add to our stock of provisions" and that they "added very

considerably to our stock of provisions, and

did not make the least expence of our European

stores, (liquors excepted;) for my people did eat nothing but fresh provisions during our

stay at this Island" (Santa Catarina, Brazil) later that year.18 However, he doesn't say anything about the process of provisioning and often speaks as if he himself arranged for provisioning.

Shelvocke only mentions that the Speedwell's purser was Mr. [James] Hendry. He does so as to note that he decided to demote him from to midshipman (the lowest ranking officer).19 Hendry happened to have formerly been the prize agent in charge of accounting for the captured goods. There is a story behind all of this, but to make any sense of it, we must turn to the other account of the voyage written by William Betaugh.

Betaugh explains that Shelvocke informed Hendry "that he ...would not be agent for the owners and Hendrie might be purser of the ship, if he pleased: at which arbitrary usurpation, Mr. Hendrie was very much shock'd; well knowing that as agent he had a right to twenty shares; but as purser, only what Shelvocke was pleased to allow, for as yet we had no such officer mentioned aboard the ship"20. Beatty pointed out that the owners had picked him to be the prize agent, but Shelvocke replied "with an oath, that if he did not accept a purser, he should neither be one nor the other."21

The replacement of Hendry as prize agent combined with Shelvocke splitting from his consort ship, the Success, gave Shelvocke control over the accounting and reporting of goods captured.

As Betaugh elsewhere says, Shelvocke "never design'd to give the owners any true account of his captures or procedings"22. An account from their basically 'in name only'

Clipperton's Success at Umatec, Guam, From A New and Complete Collection of Voyages

and

Travels (1778)

consort ship, written by her Chief Mate George Taylor, confirms what Betaugh said. According to excerpts of Taylor's journal (admittedly, found in Betaugh's book), purser Hendry "came aboard with a letter for captain Clipperton; who immediately sent back the boat for their purser to be examined... Sent away the boat: but the purser Mr. Hendrie stays; who gives but a dark story of their proceedings; and that he was not allow'd to take any account of the treasure for the owners."23 So Hendry was made purser specifically because it removed him from the decision-making. Nothing is ever said in either book about Hendry's responsibilities.

Betaugh also says that Clipperton's Success had a purser. According to an except from George Taylor's journal, "December 4th [1720] Mr. Thomas Fairman our purser departed this life; and we committed him to the deep."24 Shelvocke does mention that Clipperton had "a gang that used to go about with him to buy fresh provisions" when they had stopped at Santa Catarina Island in Brazil.25 He doesn't say who was in the 'gang', although Fairman seems a likely candidate. Unfortunately, nothing more is said of Fairman or his replacement in the excerpts found in Betaugh's book, if he even was replaced. Taylor does mention that when the reached the Gulf of Amoy (modern Xiamen Bay. China), the Success took "aboard a great quantity of rice, some cattle, fowl, wood and water" as well as 'more provisions', although there are no more details about who made the arrangements.26

1 Dampier and the Captain of the Cinque Ports had a disagreement in May of 1704, resulting in their parting company on May 19. See William Funnell, Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 46-7; 2 Shelvocke chose not to sail with Clipperton, going off on his own in the Speedwell, so these are practically two different voyages, although they were intended to sail in consort. Shelvocke does not appear to have been a very apt ship's master, wrecking the Speedwell at Juan Fernandez Island in 1720 (possibly intentionally). He built a 20 ton boat from the wreckage with which he managed to take a Spanish vessel and continue his privateering voyage, separate from Clipperton. 3 Funnell, p. 2 & 3; 4 Funnell, p. 2; 5 See Funnell, pp. 46-7 & 68-9 & Robert Kerr, A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol. 10,1824, p. 334; 6 Funnell, p. 86; 7 Ian I. Abbey, "Raiding And Trading Along The Spanish Lake: The Woodes Rogers Expedition Of 1708-1711", Doctoral Thesis, Texas A&M University, 2017, p. 95; 8 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 7; 9 Edward Cooke, Voyage to the South Seas, Vol. 1, 1712, p. 358; 10 Rogers, p. 8; 11 Rodgers mentions several examples of this in his book. See for example pp. 33, 187, 207, 239 & 246; 12 Rogers, p. 250; 13 Rogers, p. 253; 14 Cooke, p. 57; 15 George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 4; 16 Shelvocke, p. 5; 17 Shelvocke, p. 13; 18 Shelvocke, p. 31 & 51; 19 Shelvocke, p. 225; 20 William Betaugh (Beatty), A Voyage Round the World, 1728, p. 39; 21 Betaugh, p. 40; 22 Betaugh, p. 15; 23 Betaugh, p. 148-9; 24 Betaugh, p. 144; 25 Shelvocke, p. 13; 26 Betaugh, p. 162;