Organizing Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Next>>

Organization of Ship's Food In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 6

East India Company (EIC) London-Based Food Procurement Officers

The most enduring and organized merchant ship organization during the age of sail was the East India Company, who operated as an royal-chartered English monopoly until it was deregulated in 1694. A second large-scale company was created in 1697 which competed with the original company until they were combined in 1708 and joined with the government. The monopoly was essentially recreated, continuing until well beyond the end of the Golden Age of Piracy.

Because of all the intricacies of the organization and changes which occurred to its structure over time, it is somewhat difficult to pinpoint the company victualling policy during the golden age of piracy based on the resources available. However, the general outline can be discerned. After their first successful trip in leased ships, the EIC focused on building their own vessels to the specifications required for these journeys. This continued until the 1620s when they again began to look into leasing ships. They changed their business model entirely to leasing in the 1650s as the last of the company-built ships reached the end of their useful life. With this came a change in the manner of initial victualling of the ship.

The Company Owned Ships (1600-1650s)

Artist: Francis Holman - Blackwall Yard from the Thames (1784)

The East India Company was first chartered in 1600 and each voyage was initially funded as individual venture supported by joint stock owners.1 To support their ventures, the company leased docking facilities at Deptford, until it was able to purchase a piece of land next to the Royal Dockyard "near to the mouth of the Ravensbourne, where these adventurers formed a dockyard, store-houses, and other conveniences"2 in 1607.3 Because they required large ships designed to make the lengthy voyages to the East Indies, they began building such ships for themselves.

They outgrew the Deptford yard and decided the build another yard further down the Thames at Blackwall in 1614. By 1615, the yard included a smith's ship and forge, a spinning house to make rope, "and a range of storehouses for the safe keeping of timber, canvas and provisions on the western side of the yard next to the Causeway. On the north side of the yard were slaughter- and salting-houses, used for preserving and preparing meat for the voyages, which was stored in oak barrels provided by the cooper."4 Here they victualled vessels during this period, while the Deptford Yard was primarily used to build new ships.5

The number of EIC voyages began to decline in the mid 1620s causing the company to reconsider the cost of maintaining their yards and custom-built ships. In 1641, "the first [leased] ships were taken up for one voyage only, and indeed there was never enough permanence in the earlier 'stocks' to allow any other arrangement"6. These leased vessels had not been custom-built for the company, they were just ships they could hire from a non-EIC fleet. The beginning of the English Civil War in 1642 convinced them to shed their expensive-to-build-and-maintain ships and return to their initial model of leasing

Building an East Indiaman at Deptford Yard on the Thames (17th Century)

all their ships. This led the company to sell their interest the Deptford yard in 1644.7 They agreed to sell the Blackwall yard in June of 1650, although they didn't find a buyer until 1656.8

The decision to fully lease their fleet came with the establishment of the permanent joint stock company in 1657. Relying exclusively on rented vessels meant they had to arrange for ships to be built to meet the company's particular needs.9 To fulfill this need, East Indiamen consortiums were formed which purpose-built vessels for the company. These consortiums continued to use the docks at both Blackwall and Deptford for ship construction. At the same time, the Company continued to lease buildings and storehouses at Deptford to prepare and receive goods from the ships returning from the East Indies well beyond the golden age of piracy.10 So, although the sites were sold, they still continued to serve the EIC.

1 "The East India Company" History of London Website, gathered 7/15/21; 2 Nathan Dews, The History of Deptford, in the counties of Kent and Surrey, 2nd ed., 1884, p. 270; 3 C. Northcote Parkinson, "The East India Trade", The Trade Winds, 2006, p. 142 & Heidi Seetzen, "'This River Used to Be so Full of Life'", Cultural Histories of Sociabilities, Spaces and Mobilities, Colin Divall, ed., 2015, p. 101; 4 "Blackwall Yard: Development, to c.1819'", Survey of London: volumes 43 and 44: Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs (1994), pp. 553-565. british-history.ac.uk, gathered 7/15/21; 5 K. N. Chaudhuri, The English East India Company: The Study of an Early Joint-stock Company, 1965, p. 99; 6 Lucy Stuart Sutherland, A London Merchant, 1933, p. 90; 7 "Blackwall Yard, Survey of London, gathered 7/15/21; 8 "East India Company ships at Deptford", Royal Museums Greenwich website, 7/15/21; 9 Sutherland, p. 90; 10 Ralph Davis, The Rise of the English Shipping Industry, 1972, p. 259 & Dews, p. 267

Company Owned Ship Victualling (1600-1650s)

The EIC's policy regarding food procurement and storage between 1621 and around 1650 was recorded in the company's 1621 publication The lawes or standing orders. The complete sections relevant to the roles of victualling procurement, storage and issuance in this document can be found here.

Lawes or Standing Orders of the EIC (1621)

Procurement of victualling supplies was performed by committees. There were always to be at least two committees involved in every deal made for purchase of victuals to help prevent fraud and undesirable side deals. The committee members were to avoid having a personal interest in sales, lest they be declared null and void. These committees received bills of sale with details about the "waight, tare [weight of the cask containing the provisions], price, and the like... plainly set downe" which were sent to the company accountant and treasurer.1 They also reviewed 'factors' (agents in charge the overseas 'factories' or warehouses) purchase receipts, forwarding them to the company's auditors for review.

The officer overseeing victualling from the London-based yards was the Company's Husband, a term referring to husbandry - the management and conservation of resources within an organization.2 He was responsible for determining the amount of victuals needed by the EIC's ships using a table available to the accounting house for payment of items procured. The husband saw that incoming supplies were sent to the appropriate warehouse and made sure outgoing supplies were noted by the clerk of the relevant warehouse.3 Being in charge of the warehouse clerks, he provided them with "instructions and directions for the fitting and furnishing of each of the Companies Ships with their proportions of Stores and provisions, and for the ordering of their Accompts [accounts]."4

The Stores and Slaughterhouse warehouses were most relevant to provisioning EIC ships. The Clerk of Stores recorded all incoming supplies, issuing a receipt to the Husband. This clerk provided "Victuals, Marchandize, Provisions, and Stores, both new and olde, unto the Companies Ships and Yardes... by the directions of the Husband" and made sure they got aboard the appropriate ship safely.5

Detail of Warehouses and building at Deptford Yard on the Thames (17th Century)

The Clerk of the Slaughterhouse was primarily concerned with preparing meat. delivering these "Hogges and Beefes, by the number of peeces (in each Hogshead [cask containing about 63 gallons]) & waight, and to what severall Ships."6

The Clerk of the Slaughterhouse was to receive "the Remaines of all the victuals whatsoever" when ships returned to London.7 Presumably this was because all the victuals (including the non-meat victuals) were in casks and they could potentiall be viable for reissue. It would also provide a check on each individual ship's husband, helping to prevent him from selling supplies on the side. Overseeing these returned supplies were the 'Guardians for Recovery of olde Stores, Provisions and Victuals'. They received anything left on EIC ships returning form the East Indies using lighters (flat bottomed boats) and transported them to the appropriate warehouse, noting what and how much had been returned.8

1 East India Company (EIC), The lawes or standing orders, 1621, p. 44; 2 Samuel Johnson, 'Husbandry", Definition 3, A dictionary of the English language, 1755, not paginated & John Kersey, "Husbandry", A New English Dictionary, 1713, not paginated; 3 EIC, p. 14; 4 EIC, p. 15; 5 EIC, p. 16; 6 EIC, p. 35; 7 EIC, p. 36; 8 EIC, p. 38

Managing Owner/Ship's Husband

When the EIC began to focus on to chartering ships built to their specifications by owners consortiums the company's responsibility for the building and initial victualling of the ship changed. "Reorganised with a charter from the [English] Protectorate government in 1657, the Company began to flourish once more, but from this time onward it depended on the hire of privately owned ships for almost all its trading activities."1

The idea of leasing ships in this

Artist: Nicolas Ozanne

The Port of Rochefort, Seen from the Colonies Store (1776)

manner was hardly new. Merchant ships were often owned by a consortium of owners with each paying for a number of shares. The total number of shares was not typically divided more finely than into thirty-seconds. (In fact, the East India Company didn't allow shares of the ships they leased to be divided more finely than into thirty-seconds by statute.2) Such merchant vessels' owners were responsible for paying for a ship's construction and maintenance and sometimes for hiring the crew and victualling the ship, receiving their share of any profits made at the end of each voyage.

Since it was impossible for so many people to be in charge of overseeing the details of the construction and other aspects of a voyage, one of the owners usually took responsibility for overseeing these things, referred to as the 'managing owner' or the ship's husband.3 The use of the word 'husband' in this capacity dates at least back to 1723, when Edward Hatton mentioned that "most Ships, wherein several Persons are concerned, there is a Husband chosen and put in by the Owners".4 However, it was almost certainly in use before that time.

The ship's husband was the contact point for the rest of the ship's owners, being responsible for keeping track of all the land-based accounting related to its initial construction as well as preparing a ship for each voyage. At the end of the voyage, the records and accounts of the husband, ship's master and purser (if there was one) were presented to the owners by the husband.5 "Eventually [ship's husbands] were to monopolize the control of the ship in the name of the other owners, from whom they obtained a legal instrument in exchange for a bond."6 Since they were land-based, some of these men become involved in husbanding several ships. For example, ship's husband Charles Raymond oversaw 24 different merchant vessels in the 1760s.7

Artist: Wojciech Gerson

Making Arrangements, From Gdansk

in

the XVII century (1865)

When owners used their ship for their own shipments, they were obviously responsible for manning and victualling their vessel in the person of the husband or managing owner. When someone else chartered their vessel, the responsibility for victualling depended on the terms of the contract, called the charter-party. For example, in 1634, the 250 ton merchant vessel Diamond managed by 1/8 share owner Thomas Soame was chartered for the Mediterranean with the condition that he supply a crew of 40 with nine months provisions which included "great

quantities of beef and biscuit, beer and cheese, and cost £340."8 The voyage paid a small dividend on the investment. When the ship was chartered by another group in 1639 to lade fish in Newfoundland for Spain and return goods from there to England, "the owners did their best to wash their hands of all concern with the ship's earnings or her costs", leaving the hiring of the crew and victualling to those chartering the vessel.9

Although the EIC completely switched to chartering all their ships rather than building them in 1657, historian Ralph Davis notes that it is not clear when the managing partner/husband role became recognized by the East India Company. "[I]t was probably after the ending of the inter-company struggles for East India trade and of the war with France in 1713."10 When he did become a fixture in the EIC's contracts, it was the managing owner who would oversee the ship on behalf of the other owners who leased the ships to the EIC which included victualling the ship before she left England.11

EIC ships were originally loaded with the full allotment of provisions, something which changed over time. By the mid-eighteenth century, about seven months of provisions were loaded at the beginning of the voyage, enough food to get an East Indiaman to its destination with some to spare in case of problems such as the ship being trapped in a calm. It could then be re-victualled at the destination and during a stopover about midway on the return voyage.

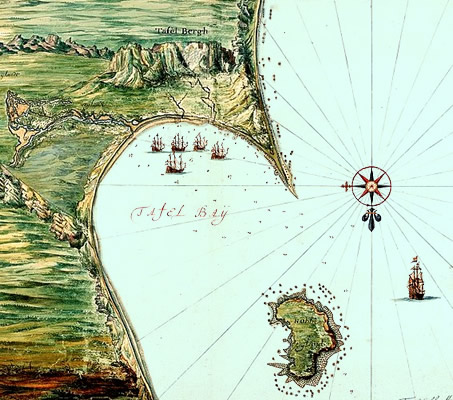

Even before their shift to the ship-leasing model, the East India Company was interested in establishing safe locations for regrouping, repair, re-victualling and whatever else they might need to do along the way to and from the East Indies. Two locations were established en route as safe ports during this period. The first was initially

Cartographer: Johanne Vingbooms,- Kaart van de Tafelbaai, Map of Table Bay and

Robben Island. (c. 1665) Note That This Map is shown South to North.

placed at Table Bay and later moved to Robben Island near the Cape of Good Hope. The EIC repeatedly attempted to establish refreshing station in these places using Newgate Prison convicts to work at them between the late 1610s and 1652.12 A more secure provisioning location was established by the Company in St. Helena Island in 1659, a location they started using as a gathering point for their convoys in 1649. A charter was granted to England in 1657 to govern the island and the company decided to establish planters there in December of the next year.13

Before the ship leasing model was fully adopted around 1657, the company's husband victualled the ships they owned, most likely from the Deptford yard on the Thames. While the EIC started leasing ships in the 1630s, it is not clear how much of the victualling of these early leased ships fell upon their owners. However, by the end of the golden age of piracy, the husband was responsible for settling all the accounts, using share capital to pay the ship's builder "and meet the demands of the suppliers of all the equipment, stores and provisions". as well as for paying the crew their advance money while it was anchored in the Thames.14 He sent the list of provisions he supplied to the company's inspectors who then forwarded it to the Court of Committees/Directors for their approval.15 Although not explicitly stated, it is likely that provisions were purchased from the advance money given to the crew while they were waiting to leave since the owners were tasked with initial provisioning of the ship..

As suggested in the example of the (non-EIC) Diamond merchant vessel, ship's husbands or managing-owners were also used by other merchant vessels. "[T]he convenience of such an agent ashore became increasingly apparent in other forms of shipping, and in the early eighteenth century there are husbands to a very considerable proportion of other merchantmen as well as to every East Indiaman. In the East India shipping system, however, the importance they retained was unique."16

1 Ralph Davis, The Rise of the English Shipping Industry in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, 1962, p. 259-60; 2 During the first half of the eighteenth century, most EIC ships were rated at 400 to 600 tons according to Davis (p. 262). By way of contrast, the majority of non-EIC merchant ships were less than 300 tons; 3 Lucy Stuart Sutherland, A London Merchant, 1933, p. 83; 4 Edward Hatton, Comes commercii; or, The trader's companion, 4th ed, 1723, p. 275; 5 Sutherland, p. 83; 6 Sutherland, p. 85; 7 Sutherland, p. 86; 8 Davis, p. 338-9; 9 Davis, p. 344; 10 Davis, p. 262; 11 Sutherland, pp. 85 & 90; 12 Jill Louise Geber, "The East India Company and Southern Africa", Vol 1, Doctoral Thesis, University College London, 1998, pp. 78-80; 13 Philip Gosse, St Helena 1502-1938, 1990, pp. 43-6; 14 Jean Sutton, Lords of the East, 1981, p. 23; 15 Sutton, p. 96; 16 Sutherland,p. 86