Organizing Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Next>>

Organization of Ship's Food In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 8

Officers In Charge of Food - Ship Pursers, Continued

Navy Purser Duties and Procedures During the Golden Age of Piracy

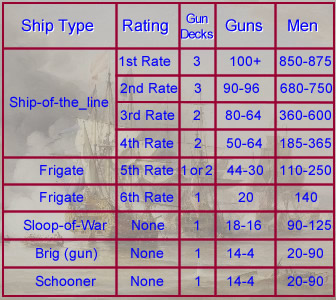

The admiralty appointed pursers to ships as warrant officers but they were overseen by the Victualling Board beginning in 1683.1 Warrant officers held their office via an authorization,

British Royal Navy Ship Ratings in the Early 18th Century, Calculated

Using Rating system of the Royal Navy, wikipedia, gathered 11/3/12,

1706 Establishment, wikipedia, gathered 11/14/12

and

1719 Establishment, wikipedia, gathered 11/14/12

Note that when counting gun decks, the quarterdeck and

forecastle, both

of which mounted guns, are not included.

typically in recognition of their having a needed skill, rather than a commission. They were the highest non-commissioned ranks in the navy. The ship's surgeon, chaplain and sailing master on a ship are other examples of warrant officers.

Unlike these other warrant officers, the purser acted more like a shipboard contractor, "a combination of paid employee and entrepreneurial businessman, allowed to sell certain items to the crew."2 The purser's navy pay depended on the rating of the ship on which he served. In 1695, pursers received £4 on month on first rates; £3 10s. for second rates, £3 for third and £2 10s. for fourth rates. Pursers were not assigned to ships below fourth rate at that time which put the captain in charge of the purser's tasks.3

Having the captain in charge of victualling proved not to be an acceptable arrangement; something the Navy Board explained to the Admiralty in 1697. Based on this, the Board recommended assigning pursers to all rated ships with more than 70 men aboard, excepting "advice boats, yachts, brigantines, sloops and the like, [which] cannot so well bear such officers."4

The duties of pursers during the early part of the golden age of piracy found in this section are primarily based upon the 1697 Victualling Instructions (which are substantially the same as the 1690 Victualling Instructions and as the 1683 Instructions). Their role in the latter part of the period primarily come from the 1731 Purser's Instructions which, as explained previously, were assembled from various letters and instructions written primarily during the golden age of piracy. In addition, references to some relevant early 18th century letters and instructions have been included.

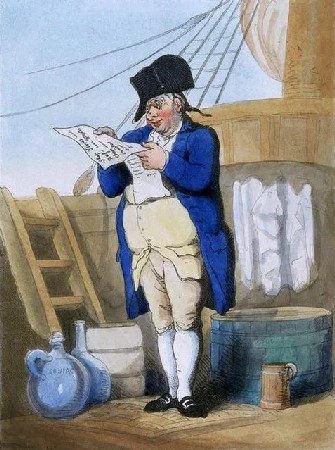

The naval Purser

Artist: Thomas Rowlandson - Ship's Purser (1799)

had to see that the victuals were "in good Condition, and well lay'd, and stow'd up".5 Daily provisions were specified with the Victualling Commissioners responsible for making sure an adequate supply of provisions were delivered to each ship. The provisions were purchased by the Victualling Committee using letters of credit (the 'course' discussed previously) based on the number of men a ship was supposed to carry.

Upon receiving the ship's victuals, the purser certified their receipt by signing an indent - essentially what we today call a purchase agreement - making the cost of the incoming provisions his responsibility. These indents spelled out the date ('in words rather than figures') and the quantity and type of provisions delivered, explaining that they were given to the purser on credit and no substitutions had been made. The pursers signed the indent, taking responsibility for the provisions. Duplicates of the document were made to be given to Comptroller of Victualling within seven days.6

Because he was financially responsible for the provisions until it was verified that they had been properly used during a voyage, the purser had to keep careful track of the number of meals eaten and the men who ate them so that his account could be properly credited for their consumption once his records were approved ('passed') by the Navy after the voyage. The purser could return any unused victuals for a credit to his account as well, although he was paid less than he had been charged for them.7The full complement of provisions required for the voyage was to be delivered to the purser's care unless it wasn't possible to put it all aboard because of issues such as a lack of supply at the victualling port, limited ship space or similar restrictions. When this occurred, credits were issued at the next victualling port stop where the ship could make up the missing provisions. At the beginning of the

Artist: Claude Lorrain

Porto de Mar com Grande Torre (c. 1637-41)

period, an exception was made for foreign voyages,

in which Case alone the Purser shall receive from the said Commissioners, ready Money for so much of the said Victualling, and at such Rates, and in such Manner, as they best can, for his Majesty's Service, without lessening the Proportions, or Goodness, of the Victuals allowed, without lessening the Proportions, or Goodness, of the Victuals allowed by his Majesty to the Seamen serving in his Ships.8

This was in recognition of difficulties of victual storage associated with long foreign voyages. The ships only had so much space available and much of the food went bad after six months of storage.9 However, "[t]oo often, the money was misappropriated, victuals ran short, and ships had to return to harbour, when on paper they should have had several weeks' provisions in hand."10

As a result of these problems, the 1701 revision of the Victualling Instructions ordered ships to get the balance of their remaining required victuals at ports where there was a victualling agent.11 This was one of the reasons behind the establishment of overseas 'outport/byport' victualling stations and victualling agents who accepted his majesty's credits in lieu of cash where no such stations were established. Some government cash for purchasing supplies overseas still found its way to the purser, however.

Artist: Pieter Sluyter - Conquest of Gibraltar by the Anglo-Dutch Fleet (1704-5)

Gibraltar was One of the Earliest "Official" Overseas Outport Victualling Stations

In 1705, the Lord High Admiral wrote the Navy Board, "where there shall be a necessity of sending money in specie [cash], the said money should be put into the hands of the purser, who is not only the proper officer, but the person charged therewith upon his indent, and who gives security to the Crown"12. While this sounds like a vote of confidence in the honesty of the pursers, they later added that the captain was to be made explicitly aware of any money given to the purser 'to buy provision abroad' so that he could make sure the money was used as intended.

When a ship ran short of provisions far from an official supply station and the purser hadn't been given money to purchase more, he "had to be prepared to lay out his own money to tide his ship over a shortage of provisions" caused by any damage to victual stores or failure of the Navy Board to have adequate provisions ready at the next victualling station.13 The purser would be repaid for such outlays at the end of of the voyage, but only if he had all the required, original documentation for these transactions and the navy reviewed, verified and passed his account.

Another source of direct payment of cash to pursers from the

A 17th Century Dutch Shipyard,

From Ships

and Ways of Other Days,

By

E. Keble Chatterton (1913)

Committee was for purchase of expendable items. These included "Necessaries, such as Wood, Candles, Dishes, Canns [mugs], Lanterns, Spoons, and other Necessaries usually provided by the Pursers of his Majesty's Ships, under the Title of Necessaries." The amount given to the purser varied the number of men on a ship, nine pence per month for those with less than 60 and six for those with more.14 The 1731 Instructions added 'Turnery Ware' to this list, which referred to round objects made on a lathe such as wooden bowls and, possibly, since canns were no longer on the list, wooden drinking vessels.15

Cash came to the purser from several other sources mentioned in the original Victualling Instructions. These included two shillings a month to cover loading the ship, four pence per ton of beer purchased by the purser, ten groats (forty pence) per month 'adz-money' (probably money to purchase tools), twelve pence a man per month while laying in a harbor and eight pence per month while at sea "being so much allowed them [the men] for extra-necessary Money: All which several Sums are to be paid to the Pursers immediately before the Signing of their Indents for Sea, or Warrants for Harbour-Victuals."16 The extra-necessary money given to him was supposed to be paid to the men for their use while in port.

When the men were given less than their full allowance of victuals either due to lack of food or a deficiency found in what there was, the purser was "to make Allowance, to the Seamen, in Money, or Victuals, at the next Victualling-Port, for such Shortness, but oblige the said Commissioners, their Deputies, Ministers, and Agents, to make present Satisfaction, to the Purser, without Delay, in the next Victualling-Port where it shall be demanded."17 Presumably the immediate cash outlay came from the extra-necessary money provided to the purser for which he would be repaid at the next port.

The rules about what was to be done with bad victuals changed rather dramatically during the golden age of piracy. The early Victualling Instructions

Throwing Cargo Overboard, (Tea, Perhaps?)

From The History of North America, By WD Cooper, (1795)

allowed pursers to sell or throw away defective provisions, according "to his Majesty's best Advantage, and to charge themselves therewith [take credit for them] upon their Accounts."18 However, this provided opportunities for pursers to cheat the system by claiming provisions were bad and allegedly thrown overboard when he actually served them to the men or brought them to foreign ports and sold them. In recognition of this, the 1701 Victualling Instruction revision said that the Victualling Commissioners, not the purser, were to "dispose of 'defective provisions by sale or otherwise to his Majesty's best advantage, the proceeds ... to be paid to the Treasurer of the Navy, and to take care he be made debtor for it in your books, in order to his being charged therewith on the front of his ledger'"19. By 1731, the Purser's Instructions strengthened this order so that if the ship were near a victualling station, the purser was "not to suffer [allow] any of the condemned Provisions to be thrown over board, except Cheese, but to return the same to the Agent of the Victualling."20 (They reiterate this point for butter adding that it could be used by the Boatswain in place of grease.21) When no such agent was available, the captain was to arrange for a survey of any victuals declared to be bad by three warrant officers from another ship. The purser thus went from complete control of the disposal of bad victuals to almost none at all by during this period.22

By 1731, the instructions added that any victuals which were destroyed either during battle or by an 'unavoidable accident' had to be certified by the ship's captain with an explanation of what had happened and how. The purser had to turn this statement in and swear that the loss wasn't due to neglect and that the damaged provisions couldn't have been saved.23 Only after review of the records of the loss would the purser's account be credited for their loss. (He was basically guilty until proven innocent in such matters.)

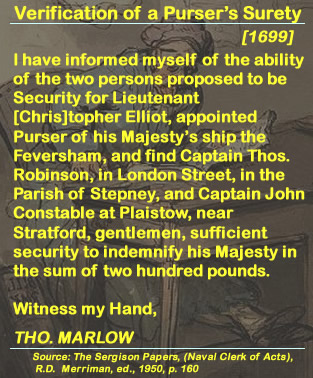

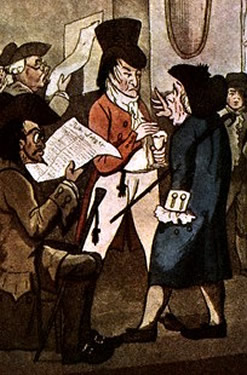

Verification of a Purser's Surety From 1699

Image Artist: Thomas Rowlandson - A Merchants Office (1789)

To make sure they were able to cover their debts, new pursers were required to provide two sureties against default, the amount varying based the rating of ship. However, these securities "cannot have amounted to much; for, although the pursers' accounts were supposed to be presented for audit immediately [when] the ship was paid off, in practice, delays were the rule rather than the exception."24 Since the purser often wound up owing the government, such delays made this difficult to collect, particularly when the purser had gone on another voyage or had died before the accounts were passed.

Some other interesting rules were spelled out. The early Victualling Instructions said that any navy vessels needing supplies at sea could 'borrow' them from other navy vessels, although the purser on the supplying ship was responsible for keeping track of what had been provided with the other ship's purser signing his list so that he could be reimbursed at the next victualling port. In cases where the next port was a foreign victualling station, the purser could be reimbursed in the amount of cash required to replace the victuals he had lent.25 The 1731 Purser's Instructions also explain that he was only to victual other ships 'by the captain's order' in writing with the other ship's purser's or steward's receipt of the supplies written on the back.26 He was then "to demand Repayment for the same from the Purser of that Ship, (unless they are chequed [stuck] there out of Victuals) and in case of Refusal, to send by the first Opportunity a perfect List of the said Mens Names, and Time of Victualling, certified by his Captain, to the Victualling Office."27

Procuring fresh water on foreign voyages could present a variety of problems, particularly where it was scarce. Sometimes local potentates charged for their water, something the 1731 Pursers Instructions recognized, although with necessary oversight. "If the Ship shall happen to be at a place where Water cannot be had without Money, he is, upon a Warrant from the Captain, to purchase what is necessary, taking Receipts witnessed by Two Commission or Warrant Officers, and a Certificate from the Captain, of the Quantity brought on board."28

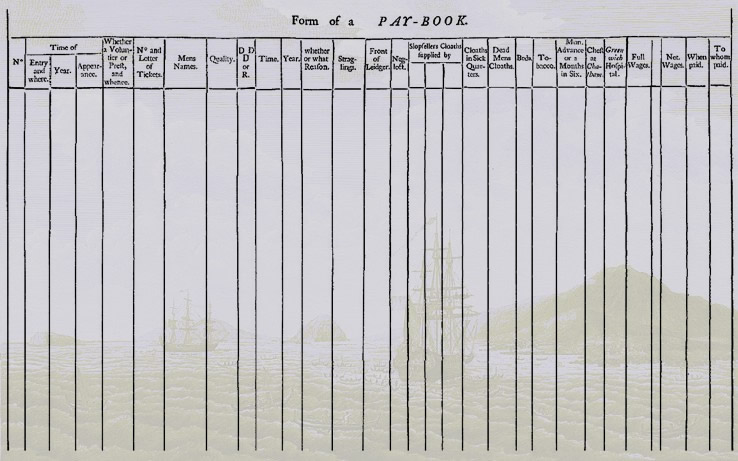

In order to be paid at the end of the journey, the purser was required to keep track of the provisions and men under his care, "producing a regular Survey thereof, according to the Custom of the Navy" so that the navy would pass his account.29 (The suggested form found in 1731 Instructions appears below.)

Purser's Pay Book Form from Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea, 1731, pp. 156-7 Background Image: Les frégates l'Astrolabe et la Boussole de l'expédition La Pérouse à Hawai (île de Maui) en 1786 (1797) |

This graphic shows the large amount of information the purser was required to track. The first eight columns focus on administrative details such as the sailor's name, number and rank ['Quality'] aboard, when he agreed to join the boat and when he appeared shipboard. The next seven columns are concerned with if a man left the ship prematurely or

Photo: Don Dunbar

Dead Man's Chest Auction Reenactment with Auctioneer William Pace

From the Fort Taylor Pirate Invasion in Key West, 2012

was absent from it and when. These include the columns headed 'D D D or R and the columns 'Straglings' and 'Neglect'. According to the Purser's Instructions, 'D D D or R' refer to "Discharge, Desertion, Death, Attendance and Absence of every Person belonging to the Ship"30 .

The next eight columns concern deductions from the sailor's pay for things provided to him before the voyage ended. This included "the Slop Cloaths [clothing purchased by the sailor from the 'slop chest' which contained new clothes, established in 1623 as noted previously], Dead Mens Cloaths [often purchased at an auction at the mast to both obtain clothes as well as support the sailor's widow], Beds and Tobacco they have been supplied with"31 along with advances on their pay.

The following two columns indicated required donations to charity. The first is for the Chatham Chest (six pence a month for regular sailors, four pence for boys) which was a fund for the benefit of wounded sailors. The second was for the upkeep of Greenwich Hospital (same rate, beginning in July of 169632), which was a hospital devoted to the care of wounded sailors. In addition, any fines levied against sailors went into the Chatham Chest before 1696 and to the Greenwich Hospital after that. The last four titled columns indicate how much and when the sailor was paid.

The process of keeping track of this information was even more complex than it appears on the form. Officers may or may not have eaten the standard victuals and the purser had to keep track of this so the officers were credited for what they didn't eat. The same could also apply to the regular sailors. "Those who had provided themselves with private stocks would take part or none

Artist: Paul Lacroix, After Joseph Vernet

Preparing Ship's Cargo, From XVIII Siecle

Institutions

Usages et Costumes France-

1700-1789, (1875)

of the purser's victuals until their own provisions ran out and they had to revert to the naval ration."33 The purser also had to keep track of periods when the men were on short allowance - that is, when rations were cut to 2/3 of normal to save victuals - so that they could be properly credited and the amount of food the purser supplied was correct. As Historian N. A. M. Rodger observes, "The keeping of a precise daily account of every man in a constantly changing ship's company over months or years was an administrative nightmare, and the least discrepancy could be disastrous"34.

The original Victualling Instructions said that any provisions remaining on a navy ship at the end of a voyage were to be returned to a navy victualling station "together with the Casks, Iron Hoops, and Biscuit-Bags"35. The boat picking up these supplies on behalf of the navy had to check and make sure they matched the account provided by the purser and then issue him a receipt for what was received. A copy of this was given to the Comptroller so that the purser's account could be adjusted to reflect the returned material.

It is interesting how often the victual containers are mentioned in this passage, which painstakingly explains that "all which Provisions, Cask, Hoops, Biscuit-Bags, &c. so returned, shall be disposed of, by the [Victualling] Commissioners, to his Majesty's best Advantage". It goes on to detail what happened to both the good and bad containers, even specifying how many staves each type of disassembled ('shaken') cask should have.36

Article twenty-seven in the 1731 Purser's Instructions ordered him to have any defective casks repaired by the cooper "without any Charge to His Majesty for Workmanship."37 The next article said he wasn't to modify casks or use them "for Washing Tubs, Steep Tubs [for soaking meat to remove salt], or by the Cook"38.

The 1731 Instructions are similarly insistent on the return of empty containers.39 Like the early Victualling Instructions, it spelled out the number of staves in each type of cask40. In addition, the purser was required to pledge "that all the Cask, Staves, Iron Hoops, and Biscuit Bags returned to the Office, were received out of His Majesty's Stores, or from Contractors" along with any remaining provisions, which had to be verified by the port officer in charge of receiving them before the purser's account could be credited for their return.41

The careful wording and detail concerning containers hints

Artist: William Holland

Lloyd's Coffee House in London (1789)

at the need to prevent pursers from selling used casks and other containers. Any missing containers were charged to him. Rodger points out that this made both the ship's cooper (the man in charge of making and repairing casks) and the ship's steward (the man in charge of dividing and handing out food to the sailors and keeping rough track of who ate what) very important to the purser. "Dishonesty or incompetence in either of them could ruin a purser, and it was necessary to pay heavily to get reliable men."42

When his account had been passed by the navy, the purser's payment was part of the 'course' of payments - a navy bill paid in sequence where lower numbered bills were paid first. This resulted in delays in payment because the government paid their bills slowly, doling out money only when they had it. "Victualling bills bore interest at 4 per cent after six months, and could be sold at a discount to brokers who dealt in them, but the purser was left with the option of further delay or less money."43 So the purser was paid for the delay, if he could afford to wait until the bill was paid.

For a purser needing money or one who was leaving on another voyage before his payment was due, it was practically a necessity to sell his bill to a broker, although only received the discounted amount. The broker could afford to wait for the bill to paid in full by the government and the interest paid for waiting created an additional incentive.

Historian Rodger points out, "The best basis for a purser's career would have been an independent fortune, but of course no man possessed of a good fortune wanted to risk it in so dangerous and thankless a career as pursery. In practice, the purser sought credit, and he was lucky to get it on easy terms from friends."44 He elsewhere explains, "A purser's real chance of wealth and success lay not in his official duties but in private business, in broking, moneylending and agency. ...Pursers often acted as bankers, making advances to their brother officers, who also had to wait for their pay."45 Thus, the purser could make his position worthwhile by exploiting the men in the same way the brokers exploited him.

1 "Pursers", Trafalgar Ancestors: Glossary, National Archives, gathered from the web 5/7/21; 2 Janet MacDonald, Feeding Nelsons Navy, 2014, p. 91-2; 3 R.D. Merriman, The Sergison Papers, (Naval Clerk of Acts), 1950, p. 238; 4 Merriman, "Navy Board to Admiralty, January 27, 1696/97", The Sergison Papers, p. 254; 5 Sieur Guillet, The Gentleman's Dictionary, 1705, not paginated; 6 Merriman, The Sergison Papers, p. 238; 7 N. A. M. Rodger, The Wooden World, 1986, p. 89-90; 8 His Majesty's Stationery Office, "Article V", Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 12, 1697-1699, 1803, p. 397; 9 J. R. Tanner, 'The Administration of the Navy from the Resotration to the Revolution,'' The English Historical Review, 1898, p. 33, Tanner, 'Introduction', A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 70 & Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 251; 10,11 Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, p. 251; 12 Merriman, "Lord High Admiral to Navy Board - 9th February 1704/5", Cited in Queen Anne's Navy, p. 273; 13 Merriman, The Sergison Papers, p. 238; 14 His Majesty's Stationery Office, "Article X", Journal of the House of Commons, p. 398; 15 Article IX", Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea,1st ed, 1731, p. 115; 16 His Majesty's Stationery Office, "Article X", Journal of the House of Commons, p. 398; 17 His Majesty's Stationery Office, "Article XIII", Journal of the House of Commons, p. 399; 18 His Majesty's Stationery Office, "Article IV", Journal of the House of Commons, p. 397; 19 Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, p. 256; 21 "Article XXIII", Regulations and instructions..., p. 116-7; 21 "Article XV", Regulations and instructions... p. 118; 22 "Article XV", Regulations and instructions... 1731, p. 118; 23 "Articles XI and XII", Regulations and instructions... p. 116; 24 "Article XXIX", Regulations and instructions... p. 124; 25 His Majesty's Stationery Office, "Article VIII", Journal of the House of Commons, p. 398; 26 "Articles XXXIII & XXXIV", Regulations and instructions... pp. 125-6; 27 "Article XXXIII", Regulations and instructions... p. 125; 28 "Article XXVI", Regulations and instructions... p. 123; 29,30,31 "Article XXX", Regulations and instructions... p. 124; 32 Merriman, The Sergison Papers, p. 217; 33 N. A. M. Rodger, The Wooden World, 1986, p. 89-90; 34 Rodger, p. 90;b 35 His Majesty's Stationery Office, "Article XI", Journal of the House of Commons, p. 398; 36 His Majesty's Stationery Office, "Article XI", Journal of the House of Commons, p. 398; 37 "Article XXVII", Regulations and instructions..., p. 123; 38 "Article XXVIII", Regulations and instructions..., p. 123; 39 "Article XXXVI", Regulations and instructions..., p. 126; 40 "Article XXXVII", Regulations and instructions..., p. 127; 41 "Article XXXVIII", Regulations and instructions..., p. 127; 42 Rodger, p. 91; 43 Rodger, p. 96; 44 Rodger, p. 88; 45 Rodger, p. 97