Organizing Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Next>>

Organization of Ship's Food In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 13

Officers In Charge of Food - Stewards, Continued

Naval Steward (And Purser) Pay

Artist: Anthony Anthony - Peter Pomegranate,(c. 1546)

There are a variety of documents regarding the pay of navy stewards and pursers. One of the earliest comes from around 1501, when the steward received one shilling threepence a week while the ship was in harbor. Pay at sea was higher; one of Henry VII's 'large' ships, the Sovereign, spent 31 days going from the Thames to Portsmouth for which the steward was paid 8s, which is about 2 shillings a week. By comparison, the purser was paid one shilling eight pence harbor rate per week and 14 shillings 8 pence for 31 days, or about 3 shillings and 7 pence a week.1

Under Henry VIII, the Peter Pomegranate, a ship originally of 450 tons, rebuilt to be 600 tons, was 'a representative ship' of the early 16th century. The ship's two pursers and three stewards salaries were each 10 shillings per month or 2.5 shillings per week. However, their pay was a little less clear because of their 'dead shares' which were essentially extra pay that was divided among the officers and sometimes even before-mast men.2

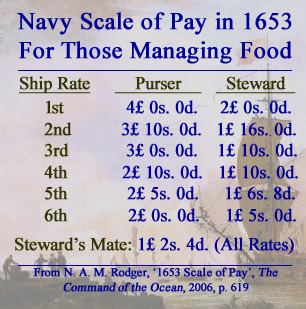

Navy Scale of Pay in 1653 for Those Managing Food

Image: Adriaen van Diest, A British Fifth Rate signalling

its arrival, (c1673-1704)

By 1653, when the government was controlled by Cromwell, the monthly navy pay rates had increased substantially. Also notable are the differences in pay given to officers serving on ships of different ratings (sizes). (This may well have been true for the previous navies, although such detail wasn't available to the author.) The navy scale pay rates for both ship's stewards and pursers appear for first through sixth rate ships in the chart at right. Note that the pay for the steward's mate(s) [assistants] is also provided, although it was the same for those serving on every ship rating. This pay rate remained in place for the most part until 1686.3

Around 1673 or 1674, former purser Captain Stephen Pyend proposed increasing the pay of the stewards on navy ships to 40 shillings a month more than the regular able seaman's pay of 1 shilling 4 pence per month and abolishing the role of the purser entirely to prevent cheating by the pursers.4 This change was not adopted, perhaps because the pursers responsibilities were taken away in 1653 and they were appointed as less powerful Clerks of the Cheque. Most of their food care and purchasing duties were given to the stewards at this time.

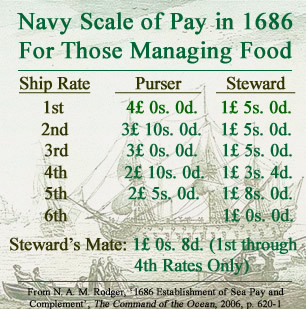

Navy Scale of Pay in 1686 for Those Managing Food

Image: Nicolas Ozanne, View of Ships of the Line (1760-80)

There were substantial monthly pay rate changes for stewards in 1686, all of them reductions from the previous pay rates. The monthly pay for pursers on sixth rate ships was dropped completely because the captain was put in charge of the purser's duties as previously discussed. The monthly pay for the steward's mates was also reduced, although not quite as significantly as the steward's pay. In addition, it was specified that stewards would only have mates assisting them on first through fourth rate ships. (This may have been true previously, but it was specifically stated.)

It is not entirely clear why the stewards' pay was reduced. However, it is worth noting that the purser usually paid the steward and his mate(s) some money in addition to their regular wage to make sure that they were diligent in keeping records of food issued to and consumed by the men. Since the cost of provisions were set against the purser's salary (as explained in the discussion of indents), the assistance of the steward and his mate(s) would have been crucial to his success.5 It is possible that the navy may have taken this custom into account when establishing the wage tables in 1686.

In 1700, the navy pay monthly rate was again adjusted. This had no impact on the pay of the stewards, the steward's mates or the purser's pay stated in the 1686 schedule. The only change impacting the food was for the addition of pursers to sixth rate ships, for whom their pay was established at 2£ 0s. 0d.6 From this point on, the pay rate remained the same until 1797. A pay rate chart found in the 1731 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea which bears this out.7

1 Michael Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, 1896, p. 41-2; 2 Oppenheim, p. 75; 3 NAM Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, 2006, p. 622; 4 J. R. Tanner, 'General Introduction,' A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 162; 5 Roger Morriss, The Foundations of British Maritime Ascendancy, Resources, Logisitics and State, 1755-1815, p. 318 & Rodger, p. 91; 6 Rodger, pp. 623-4; 7 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea, 1st ed, 1731, p. 144;

Stewards Cheating

"The Purser they cry up a high,

For honest Man; but answer Lie;

Of Stewards honesty, and his Mate,

They loudly on the Yards do Prate"

(John Baltharpe, The straights voyage or St Davids Poem, 1671, p. 30)

Artist: From the Workshop of Peter Lely

General George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle (c. 1665-6)

There were opportunities for stewards to cheat the men, although they appear far less frequently than examples of the purser cheating them.

One of the most common steward cheats was stealing the food meant for them and selling it. (As with all of these, this was also used by pursers used to cheat the system.) Speaking in general terms (as he frequently did when complaining), sailor Edward Barlow said "that [food] which two [sailors] had before must now serve three, and many times came short of that, for our steward would oftentimes pinch something out of our 'lowance" while he was serving aboard HMS Royal Charles in June of 1661.1 In July of 1662, Lisbon victualling agent Robert Cock wrote the Navy Commissioners explaining "that he has much trouble with the pursers and stewards, who steal and sell the provisions."2 He requested that all casks have the navy's identifying mark 'burnt deeply in' to prevent its being cut off and that he be given permission to seize provisions illegally sold to third parties by stewards and pursers.

Barlow discusses a second type of cheat in his diary. While serving on the HMS Monck in 1666 he told of a purser who had cheated the men of some of their short allowance money. He once again generalized this occurrence, explaining that "in this manner are poor seamen many times abused by pursers and stewards."3 It is doubtful that a steward would usually have been allowed to handle cash, this likely being jealously guarded by the purser. The exception would be when there was no purser on sixth rate or smaller navy vessels.

There is some information about the punishment of stewards caught stealing food. In 1653, steward Joshua Hunt was court-marshalled for 'embezzlement of stores' and was given the choice of making restitution or being punished. General George Monck's report "remarked that the prisoner had only been

Artist: Thomas Hosmer Shepherd - A debtor in Fleet Street Prison.(early 19th c)

found out in that [type of crime] which most stewards did, and that he would be sent up to London to give his friends or sureties the opportunity of making amends; if they failed to do this he was to be returned to the fleet for corporal punishment at the decision of a further court-martial."4 The punishment would most likely result in Hunt being put in debtor's prison until the debt was paid. Another example comes from commander commander Thomas Allin's service aboard the 3rd rate Plymouth during April 1661. He mentions "a complaint against the steward and his mate for want of weight of butter and cheese, and had their promises never to offend in the like, if they do, I have promised them a whipping at the mainmast."5

In response to accusations made by the cook on HMS Squirrel in 1708 of the steward cheating the men, Captain James Hadsell had the steward brought before the ship's company. Hadsell explained that if he heard "any manner of complaint made by any of my men of their being wronged, I would punish him very severely."6 However, Hadsell's true purpose wasn't to punish the steward for wrong doing; it was an attempt to stop the cook from inciting the sailors to mutiny by convincing them the steward was cheating them.

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of His Life at Sea, 1559 -1703, 1934, p. 51; 2 J. R. Tanner, 'The Administration of the Navy from the Restoration to the Revolution', The English Historical Review, 1897, p. 30; 3 Barlow, p. 271; 4 Michael Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, 1896, p. 357; 5 The Journals of Sir Thomas Allin, 1660-1678, Volume I, R. C. Anderson, ed., 1660-1678, Vol 79, 1939, p. 32; 6 R. D. Merriman, Queen Annes Navy, 1961, p. 195

Steward Informants

The steward was in a unique position to catch pursers and captains twisting the victualling system to benefit themselves. Nathaniel Boteler explained that when the steward's role is "cautiously conferred [bestowed upon him], and [his duty is] honestly discharged, it may be made use of for many needful discoveries, and serve as an over-awing [deterrent] of all such Abuses and cousenages [cozenages - deceitful practices] as may be practised that way."1 Although most of the examples found here come from the records of the English navy, there are also examples of steward informants from a merchant and privateering ship. (While this suggests broader support for steward informants it doesn't necessarily prove that they were more common than steward cheaters.)

HMS Adventure (1646), A 40-gun Fourth-Rate Ship, (c. 1673)

An example of a naval steward informant concerns Captain John Tyrwhitt of the fourth rate ship Adventure between 1671-3. Tyrwhitt was accused of keeping men on the ship's books who had run away so that their wages would be paid to him after they had left, which he could then pocket. Mr. Swann, the steward on the ship, discovered and reported this, which Tyrwhitt didn't deny, even though "nothing further appears in proof of it than the allegations of the said steward, the present informer, who was not only privy but combining with the said commander in the abusing of the said books"2. It is curious that Tyrwhitt didn't protest the charge given that he had to work with Swann to make the cheat work. Even more interesting (and perhaps a little damning) was that Swann was given a reward of a third of Tyrwhitt's salary which the captain was denied as a result of the theft, despite the steward's apparent involvement in the cheat. (It is not stated whether he received any part of the money Tyrwhitt was charged with taking.)

A slew of cases of fraud on ships were uncovered by a 'Mr. Jones' beginning in

Artist: Willem van de Velde the Elder - HMS Dover (1654), A 48-gun Fourth-Rate Ship, (c. 1673)

February of 1674. He identified these cheats "by false entries, discharges, and rating ... in the paybooks of several of his Majesty's ships, and particularly upon the following, viz.—Stavoreen, Ruby, Reserve, Thomas and Francis, Adventure, Speedwell, John of Dover,—to the value of about £3000 in the said 7 books."3 Curiously, all of these ships listed were fourth rates or below. The Stavoreen, Ruby, Reserve, and Adventure (which was the same as mentioned in the first example) were fourth rates and the John of Dover probably refers to the Dover, another fourth rate. The Speedwell was a fifth rate and the Thomas and Francis was a hired ship of unknown rating or tonnage. The account goes on to explain that Jones testimony came from "stewards of the ships wherein the frauds are found, and actors in the said frauds, but pardoned, as Jones pretends, by his Majesty's promise to him in the presence of my Lord Keeper and my Lord Treasurer in order to their conducing them to confess."4

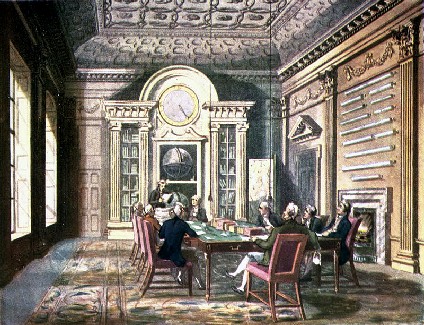

As the above suggests, the Admiralty harbored some suspicions of Mr Jones

Artist: Thomas Rowlandson

Board Room of the Admiralty, From Microcosm of London, Plate 3 (1808)

and his methods, and with good reason. "Mr. Jones insisted 'peremptorily' upon an advance of £500, in addition to £200 which had been already supplied him from the privy purse and £200 more from the Lord Treasurer. The Lords [of the navy] made several futile efforts to extract from Mr. Jones a detailed account of his past disbursements

but obtained 'no sort of satisfaction'"5. The navy Lords examined the ships' books themselves, finding little return for the money they had given Jones. They then decided "that no more [advance] money would be forthcoming, although Jones was encouraged to further [prosecute his] investigations and promised one-third of any moneys which he might succeed in recovering for the King."6 Jones didn't agree with this deal and made repeated requests for advance money, although he continued to unsuccessfully seek evidence of systematic fraud through July of 1675. In his defense, Jones did manage to turn up some evidence of cheating by pursers of the Adventure and Speedwell and likely helped identify the 'unfaithfulness' of the assistant purser of the Stavoreen, thanks to some of his steward witnesses.7

Just because naval stewards could be reliable

From The English Lion Dismembered (1756)

informants doesn't mean that they always were. An accusation was made by commander Robert Johnson of the 4th rate Exeter against ship's purser Mr. Savage while the ship was at sea in the fall of 1721. This led to a court martial overseen by the commodore of the voyage and five other navy ship's captains. Johnson accused Savage of high crimes and misdemeanors because he was "a very drunken beastly Man, and that he was come out of Exeter without Money, or any other Conveniencies for the Supply of the Ship's Company; and that he had taken the Government's Money, in order to supply such Necessaries as are proper for so long a Voyage; but had not supplied the Ship with any Tobacco, nor Slop [clothing] Goods, as is customary for Gentlemen in his Post."8 By way of proof, Johnson had 'his steward and many other Officers' testify against Savage. In his defense, Savage said that he had been brought to the ship too late to purchase "common Necessaries, which the Ship could not do without; as Candles and Lanthorns, &c."9 The judges sided with the purser leading them to look into the story more deeply. As a result, "it was proved that his Steward had been a very great Rogue to him, for which he [the steward] was dismissed [from] his Post"10.

The two non-naval accounts of stewards testifying actually have nothing to do with food, although since they are from a merchant and a privateer ship, they are included here. The privateer account is from Woodes Rogers' voyage aboard the Duke. Some of the sailors were talking about mutinying. Rogers reported, "The Steward told me, that several of them had last Night made a private Agreement, and that he heard some Ring-leaders by way of Encouragement boast to the rest, that 60 Men had already signed the Paper."11

Sailor's Round Robin Document (Early 16th Century)

The merchant account comes from captain Nathaniel Uring of the Hamilton Frigate. When they were on the coast of Mexico to load logwood in 1712, "one Night, about Eight a Clock, my Steward secretly acquainted me that the Seamen were conspiring to run away with the Ship; and in order thereunto they had made a Round Robin, which many of them had sign' d, and had desired that he would sign it also, which he had promised to do: But he not knowing what might be the Consequence, thought it his Duty to inform me of it."12 Round-robins were documents which were agreed to by the crew, who signed their names in way which formed a circle. (See the example at right.) This was to prevent anyone one from discovering who had started the document - and thus encouraged the crew to mutiny - if it should be captured and used in evidence at a trial.

Although neither instance has anything to do with the theft of victuals, they do suggest that the steward was considered an important witness when prosecuting crimes. Both also suggest that he was considered one of the regular sailors by the crew rather than an officer of the ship, given they that tried to include him in their plans.

1 Nathaniel Boteler, Colloquia maritima or Sea Dialogues, 1688, p. 20; 2 Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, Vol IV, J.R. Tanner ed, 1903, p. 70; 3 Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, Vol. IV, J.R. Tanner ed, 1903, p. 134-5; 4 Naval Manuscripts..., p. 135; 5 Naval Manuscripts..., p. lxxxvi-lxxxvii; 6 Naval Manuscripts..., p. lxxxvii; 7 Naval Manuscripts..., p. lxxxviii; 8 Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 84; 9,10 Downing, p. 85; 11 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 234-5; 12 Nathaniel Uring, The Voyages and Travels of Capt. Uring, 1928, p. 176