Organizing Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 <<First

Organization of Ship's Food In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 18

A Ship's cook room

"The problems of preparing and cooking food beyond the stable confines of a permanent kitchen might seem a minor issue to the majority of us. For some it was of paramount importance, particularly for those involved in sea-faring. How do you cook for sixty or more men (and sometimes women) aboard ship, without setting light to the vessel, in a cramped space with concern for any additional weight, and with the possibility of being attacked by foreign ships or being caught in a storm?" (Helen Clifford, "Patents for Portability, Cooking Aboard Ship 1650-1850", Food on the Move, 1997, p. 52)

Artist: Thomas Phillips

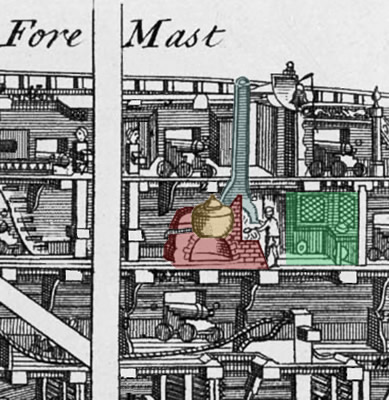

Cook Room & Chimney, From Section Through a First-Rate (c. 1690)

If ships were to serve hot food, they needed a place to do it which could safely hold a fire. It would have to be located in such a way way that if a ship came under attack or sailing in rough seas, the room would experience a minimum of motion that might upset the fire. The room had to be large enough to cook meals for a large number of men, yet take up only as much space as necessary. First rate navy vessels during the golden age of piracy could have eight hundred men or more, although the food was not cooked for all of them at the same time. Restricting the footprint of the cook room was desirable for each type of ship; the navy wanted to allocate much of their space for guns, merchant ships wanted the maximum amount space for storage of merchandise and privateers, buccaneers and pirates all had to have sufficient numbers of men and guns, in addition to sufficient space to hold the treasures they captured. Llike the cook himself, the cook room of a ship was something of a necessary evil that had to be accommodated for the sake of the men.

Throughout the golden age of piracy and beyond, this room was referred to only as the 'cook room'. The word 'galley', in popular use today, isn't found in print until 1750, when Thomas Blankley defined it as "a Place in the Cook-Room, where the Grates are set up, and in which they make Fires, for boyling or roasting the Victuals."1 Even this definition refers to a particular feature found in the cook room, not the room itself. A physician's book translated from Dutch in 1762 is the first the author found which equates the word 'galley' to 'cook room,'2 so the connection of the word to the room was probably established between the two dates.

In the late 16th century, food on most ships of any size "was prepared on hearths built of some fifty bricks and situated in the hold above the wet ballast as greater security against fire."3

Photo: Peter Isatolo

A Model of the Cramped Cook Room of the 1628 Vasa

This produced "a solid brick-built oven and firebase low down in the hold. These [cook rooms] not only guaranteed hot food under all but the most adverse conditions, they also provided additional ballast, which would not shift in a heavy sea."4 The normal ballast that this oven sat uponwas hardly a sanitary environment; water which broke over the ship in rough seas would make its way down the from the top decks to the ballast, washing whatever it encountered on its way down to rest in the putrefying liquid in the ballast.

Historian Brian Laverly explains that little is known about early seventeenth century cook room stoves. He points to what was found aboard the 1628 Swedish warship Vasa (a model of which is seen at left) when it was salvaged in 1961 as a possible model for cook rooms of the period.5 It is interesting that the room was enclosed in brick while most of the period images from the GAoP and the descriptions for English ships of the same period suggest the oven was the only thing constructed of brick.

On navy ships, the cook room of the late seventeenth century consisted of two huge copper kettles encased in a brick furnace. Laverley provides a fairly detailed description of the setup commonly used on navy ships before 1750:

Bricks were placed all round the pit, enclosing the kettles (except for their tops), leaving an opening on one side. This was closed by an iron door, which was hinged and could be bolted shut. Horizontal pipes ran through the brickwork, forward of the kettle. The ash pit also had an opening in the top to allow the smoke to escape through a funnel. Several layers of brick were placed under the ash pit, to keep the fire away from the wood of the deck.

This was the most basic type of firehearth, and was suitable only for boiling. Parts were added to the structure to give scope for more sophisticated cooking. In the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the brickwork on the after side of the main stove formed a separate furnace, with iron racks for grilling. This was used for the officers' food.6

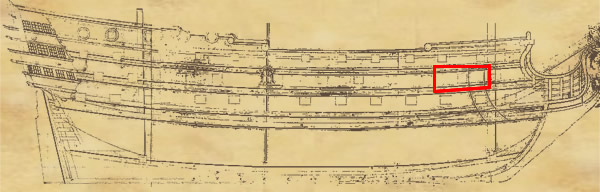

An example of this type

Cook Room on Third Rate Navy Ship Showing Stove, Kettle, Chimney and

Food Prep

Area, From Cyclopedia, Vol 2,

By Ephraim Chambers (1728)

of firehearth can be seen in the image at right highlighted in red. The distinction between the preparation of the regular sailor's food, boiled inside the large kettles, and the officer's food which could be roasted is worth reiterating. The size of the furnace on navy ships varied based on the number of men there were to feed. On a first rate navy vessel, 2,500 bricks were required to enclose the furnace. 1500 were used on a third rate and 600 on a Sixth.7 The kettles inside their brick housings ( highlighted in the image in yellow) were made of copper and were constructed using

several plates riveted together. The late seventeenth century kettle appears to have been round in shape, rather like a cauldron. By the 1700s it was cylindrical, with a height of about two-thirds its diameter. A horizontal pipe with a tap was fitted near the bottom of the side, to run off the water. The bottom of the kettle was flat, or slightly curved. The top had a removeable lid, about half the diameter of the whole kettle. By the 1680s, all ships of the Sixth Rate and above had two kettles, placed side by side in the furnace. They were known as the fish kettle and the small kettle.7

The last part of the stove was the chimney (highlighted in blue on the image), which was necessary because the cook room was always located below deck. Laverley explains that it was built in two parts, the lower part, extending from over top of the oven and going up through the decks, and the upper part above the main deck which directed the smoke high enough so as not to offend those on the top decks. "Though copper is mentioned as a material for chimneys as early as 1686, most of the early eighteenth century ones seem to have been made of wood."8

There was also a preparation area (highlighted on the image in green) shown with a table and window on the right side of the image. Historian Laverly explains, "At the after end of this [cooking] compartment, on the side of the stove which was traditionally used for preparing the officers' meals, were shelves and working surfaces for food preparation. In the late seventeenth century, on Third Rates and above, this area was often fitted with mica or glass windows."9

Writing about the cook room in the 1640s, Nathaniel Boteler said that navy ships had a "Multitude of Men, which require necessarily the dressing of much Meat [meat is probably used here generically to refer to food,

Trencher, Spoon and Knife

itsometimes did in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries], and as necessarily a large and private Room to dress it in."10 In line with this, Sieur Guillet says that the cook room is where "the Victuals are Dress'd"11, using a more recognizable term for the type of food being prepared.

There are a two references to the tools found in a merchant ship's cook room, which were probably minimally stocked to save money. The records of Thomas Bowrey list the things put aboard the Mary Galley, a 167 ton merchant in 1704. Unfortunately, the only cooking implements specifically mentioned are found in a message to an ironmonger which includes a "Cookes Stores cask containing": 1 Chopping knife, 3 Iron Candlesticks and a Chafing dish.12 It is unfortunate that letters to other vendors aren't included in the material found on the Mary.

The 1676 information for the 100 ton merchant vessel Welcome is more detailed, mentioning a "stew pan, frying-pan, spit, pot, tongs, brass ladle and flesh fork, twelve pewter spoons and twelve trenchers [flat plates, sometimes round, sometimes square with a round indentation - see the illustratio above] which, though simple enough, suggest frying and roasting as well as boiling."13 This pre-GAoP reference to roasting and frying is very interesting because these were cooking procedures

Cooking Stove Spits, Section Through a First-Rate, Thomas Phillips (c. 1690)

suggested not to be common in the navy (outside of cooking for the officers). It is sometimes assumed that merchant ships provided food for their sailors that was even worse than the navy in an effort to save money, however this appears to contradict that belief.

In fairness to the navy, they appear to have used the spits on occasion to roast meat for everyone during the latter part of the period. HMS Salisbury midshipman Clement Downing says that when the ship was at Anjouan in the Comoros Islands in July of 1721, "Our Ship's Cook-room was soon furnished with three or four Spits one above another, from four in the Morning till eight at Night; this Refreshment put all our People into good heart again."14 However, this appears to suggest that the large quantity of spits were set up temporarily to improve morale on the ship rather than as a regular practice. Still, it does suggest that the navy vessel was capable of roasting meat in large quantities when in port.

1 Thomas Riley Blankley, A Naval Expositor, 1755, 2nd ed., p. 62; 2 Salomon de Monchy, An Essay on the Causes and Cure of the Usual Diseases in Voyages to the West-Indies, 1762, p. 147; 3 John Keevil, Medicine and Navy, Vol. 1, 1957, p. 72; 4 David Loades, The Tudor Navy, An Administrative, political and military history, 1992, p. 34-5; 5 Brian Lavery, The Arming and Fitting of English Ships of War, 1600-1815, 1987, p. 196; 6 Lavery, p. 197; 7 Lavery, p. 196-7; 8,9 Lavery, p. 200; 10 Nathaniel Boteler, Colloquia maritima or Sea Dialogues, 1688, pp. 125-6; 11 Sieur Guillet, The Gentleman's Dictionary, 1705, not paginated; 12 Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey 1669-1713, 1927, p. 177; 13 Peter Earle, Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775, 1998, pp. 87-8; 14 Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 82

Cook Room Location

The location of the cook room on a ship was hotly debated during the early/mid seventeeth century.

Sir John Hawkins, From the National Maritime Museum (1581)

By the fifteenth century, the cook room included "a solid brick-built oven and firebase low down in the hold", serving double duty as cooking location and ballast.1 It continued to be located there well into the seventeenth century, despite much discussion about problems associated with this. As early as 1578, Admiral Sir William Wynter, Surveyor and Rigger of the Navy and Master of Naval Ordnance proposed moving the cook room to the forecastle. Although not relocated as standard procedure on navy ships of the period, Sir John Hawkins chose to have the cook room on the Mary Rose moved from the hold to the forecastle, "well for the better stowinge of her victualles as also for better preserving her whole companie in health during that voyadge beinge bounde to the southwardes."2

In 1618, the Jacobean Commission of Enquiry recommended that navy ship cook rooms should be placed in the forecastles,

because [cook rooms placed] in the midship and in [the] hold [cause] the smoke and heat [to] so search every corner and seam, that they make the oakum spew out, and the ships leaky, and soon decay. Besides the best room for stowage of victuals is thereby so taken up [so] that transporters must be hired for every voyage of any time and which is worst, when all the weight must be cast before and abaft and the ships are left empty and light in the midst, it makes them apt to sway in the back.3

The problem of placing most of the weight at the ends of a ship was called 'hogging', something which caused the keel to bend upwards when riding on waves.4 Laverly explains that following this pronouncement, "two-deckers and smaller ships carried the cook room under the forecastle, forward on the upper deck. On three-deckers it was forward on the middle-deck, so its chimney had to pass through two decks before discharging its smoke. …The very smaller vessels sometimes had it amidships, because there was so little space in the bows."5

Photo: Chinmayee Mishra - Vasa Museum Ship Model Showing Cook Room (Outlined In Red) Located in Ship Center, Orlop Deck |

A variety of treatises were written in the 1630s and 1640s, each of which had something to say about the location of the cook room on a ship. John Smith, writing some time before 1631, wrote:

The Cook room where they dress their Victuals may be placed in divers places of the Ship, as sometimes in the Hould, but that oft spoileth the victuals by reason of the heat, but commonly in Merchant-men it is the Fore-castle, especially being contrived in Furnaces; besides in chase their Stern is that part of the Ship they most use in fight, but in a Man of War they fight most with their Prow, and it is very troublesome to the use of his Ordnance, and very dangerous lying over the Powder room, some do place it over the Hatches way, but that as the Stewards room are ever to be contrived according to the Ships imployment, &c.6

In the 1640s, William Monson advised that "[t]he greatest inconvenience in his Majesty's ships is the placing the cook-room in the midships, and so low in hold that many discommodities and dangers arise by it"7. Among them were two things mentioned by the Jacobean Enquiry: 'hogging' the ship and issues caused by smoke in the lower decks from a fire located low in the ship. He added two other problems: the difficulty of putting out fires which started in the hold cook rooms versus those which were 'aloft and in the forecastle' and the impact of the heat in the lower decks on the health of the men.

Artist: Thomas Phillips - Section Through a First Rate Navy Ship Showing the Cook Room and Chimney (In Red) Located in Forecastle (c. 1690) |

Writing around the same time, Nathaniel Boteler stated that cook rooms were 'variously seated in Ships'including the forecastle. "In some other Ships, it is seated in the Hatch-way upon the first Orlope [one deck above the hold]; and for Ships of War (which are termed Men of War) it is most properly there, in regard of danger by Fire, and the freer use of the Guns, that lye in the Fore castle". The concern about fire presumably refers to the cook room's location below the waterline where it would be less likely to receive shot from attacking vessels and less likely to shift as much as it would if located higher up and further fore or aft. This statement makes it sound as if Boteler prefered the cook room to be near the hold in Men-of-War. However, he goes on to say, "But for mine own part I cannot apprehend, how it can be otherwise placed, than in the Fore-castle, in great Ships"8.

The final comments come from Henry Mainwaring, a navyman and former pirate. Writing in 1644, he said that

Artist: Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom

Forecastle Bulkhead (Outlined In Red) on a Dutch East Indiaman (1600)

for men-of-war, it was "most inconvenient to have it in the Fore-ship or Fore-castle"9. He goes on to list several reasons he thinks this, most of which have to do with battle. Among his concern was that it would displace cannons as well as place the cook fire located above the place where gunpowder was stored. He also notes that a large navy ship fights "most with his Prow, that part is likewise to receive shot, which if any chance to come amongst the Bricks in the Cook-room, they will spoil more men than the shot [referring to broken brick shrapnel hit by cannon fire]: and besides, the Cook-room it self for that voyage is spoiled, there being no means to repair it at sea, and then they must needs use another"10. He adds that this position is likely to cause fires because it extends from one side of the ship to the other. Finally, "It takes away the grace and pleasure of the most important & pleasantest part of all the ship: for anyone who comes aboard a man of War, will principally look at her Chase [the location of the chase guns], being the place where the chief offensive force of the ship should lie."11

The complaint about aesthetics appears to refer to the idea that a cook room required the construction of a forecastle bulkhead, which he would interfere with the sleek lines of a ship and operation of the chase guns.12 (Pirates typically removed these structures on captured ships they took over - called a razee - in order to make them faster.) Historian Brian Laverly explains that in the seventeenth century the cook room was placed behind the forecastle, being one of three forecastle bulkheads. (The other two, placed on either side of the cook room bulkhead, accomodated officers cabins. "In the eighteenth century the bulkhead became straighter, though the cook room still projected slightly. Even though the galley on a three-decker was on the deck below, the bulkhead of the forecastle was of similar shape."13

Artist: John Clevely the Elder

Deck Locations on an English Sixth Rate on Stocks (1758)

Mainwaring's is the lone voice among the four commenting during this period to suggest the cook room be placed near the bottom of a warship. He recommends locating it "in the Hatch-way, upon the first Orlop (not in the Hold, as the Kings ships do, which must needs spoil all the Victuals with too much heating the Hold, or at least, force them to stow it so near the Stem and Stern, that it must needs wrong and wring the Ships much, and lose much stowage". He explains that when placed on the orlop, "it doth wonderfully well air the Ship betwixt the Decks, which is a great health unto the Company"14. This is a reference to the cook room being located in the hatchway which was open from the hold to the main deck. His comment is curious because some smoke would have still found its way around the lower decks.

Mainwaring finishes noting that he'd prefer a ship not have a permenant cook room at all, preferring one which could "be removed, and strooken down in Hold if I list [the ship tilts to one side], and yet it would waste no more Wood than these do, and dress sufficient Victuals for the company, and roast or bake some competent quantity for the Commander, or any persons of

Men Preparing Food, From De Verstandige Kock of

Sorghvuldige Huyshoudster (1677)

Quality."15 Boteler mentions that while it could be useful "if this cook room (as some conceive) may be contrived to be movable, and so in a Fight, be struck down into the Hold of the Ship"16, however his parenthetical comment is skeptical. He prefers the cook room to be placed in the forecastle, as we have seen.

Mainwaring was not entirely opposed to locating a cook room in the forecastle. On merchant ships, he counsels that this is the best place to place it since they needed their hold to stow goods. He adds that such a location is useful "for the saving of wood in long Journeys: also for that in Fight, they bring their stern and not their prow to Fight, and therefore it will be less [of a] discommodity to them; besides they do not carry so much Ordnance forward on, and and therefore the weight of the Cook-room is not so offensive [as it is] in a Man of War"17.

Whatever the arguments were in favor of putting the cook room in the forecastle, historian J. D. Davies says that the location didn't work well as implemented in the first half of the seventeenth century. As a result, "in the 1650s it was moved back to its traditional location in the hold, where it caused the same problems as before. In the 1660s it was moved back to the forecastle, on the upper deck in two-deckers and the middle-deck in three-deckers; but on smaller ships with no forecastle, it stayed in the hold"18. Laverly shows a plan for the 1711 rebuild of the second rate HMS Ossory (renamed HMS Princess

Deck Plan of the HMS Ossory (1711) Approximate Location of Cook Room Outlined in Red

at that time) which places the cook room on the "middle gundeck".19 He adds that the small ships didn't have chimneys, although some inventive commanders devised them to help clear the smoke from the lower decks. Although the forecastle location found favor during the golden age of piracy, it remained located in the hold on some ships. Sieur Guillet's 1705 dictionary says, "In some Ships, [the cook room] ’tis seated in the Hold; but generally in the Fore-castle, where there are Furnaces contriv'd, and other Necessaries, for the Purpose."20

1 David Loades, The Tudor Navy, An Administrative, political and military history, 1992, p. 34; 2 Michael Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, 1896, p. 128; 3 The Jacobean Commissions of Enquiry 1608 and 1618, A. P. McGowan, ed, 1971, p. 289; 4 Michael Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, 1896, p. 206; 5 Brian Lavery, The Arming and Fitting of English Ships of War, 1600-1815, 1987, p. 195-6; 6 John Smith, Seamans Grammar and Dictionary, 1691, p. 12-3; 7 William Monson, The Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson, Vol. IV, M. Oppenheim, ed., 1913, p. 65; 8 Nathaniel Boteler, Colloquia maritima or Sea Dialogues, 1688, p. 125; 9, 10 Henry Manwaring, The sea mans dictionary, 1670, p. 28; 11 Manwaring, p. 29; 12 Lavery, p. 200; 13 Lavery, p. 200; 14,15 Manwaring, p. 29; 16 Boteler, p. 125; 17 Manwaring, p. 28; 18 J. D. Davies, Pepys's Navy, 2008, p. 77; 19 Lavery, p. 159; 20 Sieur Guillet, The Gentleman's Dictionary, 1705, not paginated

Other Aspects of Shipboard Cooking

In the navy, the cook room was the province of the cook and those who worked with him to prepare meals only. Monson outlined this in the mid-seventeenth century, explaining that "for the better ordering of victuals there are divers officers appointed in sundry rooms, as stewards to give it out, meaner persons [sailors appointed by their mess] to serve it,

Artist: Thomas Phillips

Section Through a First Rate Navy Ship Showing

the Fore-Peak (In Red)

and the Cook Room (In

Blue) Near to the Location of the Cook's Quarters (c. 1690)

men to look to the shifting of it in water, and cooks to the dressing of it; so that no man but upon courtesy is admitted to have access into the cook's room, except the officers of the room."1 Supporting this, Laverly explains that beginning the late seventeenth century "the galley was sealed off from the rest of the forecastle within a six-sided compartment, which ...helped to prevent the pilfering of food, and perhaps also... protect[ed] the stove from damage in action".2

There are two other rooms of interest which concerned the English navy cook. The first was a small, oddly shaped compartment called the fore-peak. The odd shape comes from one wall being the prow of the ship. It was here that wood and coal used in the cook room stove were stored.3 This room can be seen outlined in red in the image at right. The second room of interest was the cook's quarters. The 1673 Establishment of Cabins mentions them being in the forecastle bulkhead on the starboard side of the ship for third through fifth rates.4 It doesn't specify a space for them for other ship rates. This would have been near the cook room (outlined in blue), which makes sense.

Most of this information comes from what was done on navy vessels in the two centuries before and during the golden age of piracy. However, there is a much more ancient method of cooking on ships which is supported by at least one period account. During his privateering voyage designed to attack Spanish shipping and South American outposts from1719-21,

Artist: Pieter Bout

Cooking on a River Craft, From A view of the Pont de l'Isle de la Cité

and the Tour des Nesle from the left bank (late17th, early 18th c.)

George Shelvocke wrecked his ship Speedwell at Juan Fernandez Island in the summer of 1720. In order to escape the island, the ship's carpenter oversaw the construction of a small barque which they named Recovery. They sailed from Juan Fenandez towards the mainland on October 6,1720. Shelvocke records, "all the conveniency we had for a fire was only a half tub fill'd with earth, which made it so tedious that we had a continual noise of frying from morning till night."5 This would have been built on the main deck, open to the air. Small, portable cook stoves could be placed on any earthen mineral (slate and bricks were commonly used as ballast and would have protected a wooden deck fairly well).

However, it must be remembered that Shelvocke's crew created this cooking platform out of necessity. It is unlikely that a portable cook-stove on a earthen platform would have been used on an English ship with any reasonable number of crewmen on a voyage away from shore for an extended period. Thomas Bowry's small East India merchant Mary galley (1704), boasted a crew of only twenty-six sailors, yet it included a purpose-built cook room in a cabin on the lower deck.6 Still, outside of needs must, a very small vessel or one which didn't stray more than a few days from a coast might have employed such a cooking arrangement.

1 William Monson, The Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson, Vol. IV, M. Oppenheim, ed., 1913, p. 64-5; 2 Brian Lavery, The Arming and Fitting of English Ships of War, 1600-1815, 1987, p. 200; 3 Lavery, p. 189; 4 A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, J. R. Tanner, ed, 1903, p. 190-2; 5 George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 260; 6 Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey 1669-1713, 1927, pp. 134 & 187