Organizing Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Next>>

Organization of Ship's Food In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

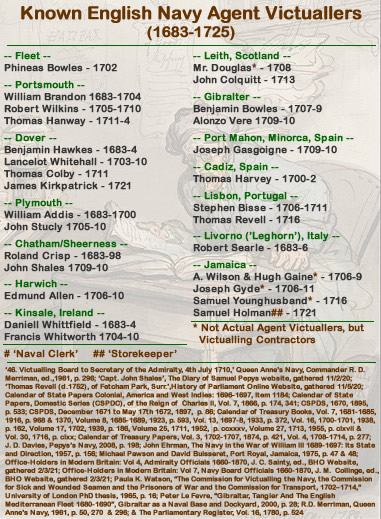

Officers In Charge of Food - Navy Agent Victuallers

Agent Victuallers were responsible for overseeing the inflow and outflow of provisions from their victualling station as well as the people stationed there. These posts were created by the Victualling Committee in December of 1683, replacing the previous system which relied on contracts

Known English Victualling Agents, 1683-1725

Background Artist: Thomas Rowlandson - A Merchants Office (1789)

with local vendors. A list of the Agent Victuallers by location from their first appointments in 1683 through the end of the Golden Age of Piracy in 1725 can be found at right. Note that this list is based solely on service dates that were found in records to which the author had access. Many, likely all, of these agents served in periods outside those indicated here. Other agents not found in the records were probably assigned to these locations during years not listed. Although far from complete, the list gives some insight into the men who served the navy in this capacity during the period of interest.

There was a difference between Agent Victuallers stationed in the English victualling yards (which included the Irish and Scottish yards) and those overseas. The 'foreign' victualing yards were responsible for overseeing food processing at their location while processing in the yards located in England (and the later United Kingdom) were managed by the master baker, brewer, butcher and cooper at the London-based Tower Hill Victualling Yard.1 In addition to the recognized Victualling Stations, other foreign locations existed which were served by local contractors. Acting in some ways like a local Agent Victualler, the contractor corresponded with the Victualing Board and delivered provisions at an agreed upon price. This system worked well when the English were at peace, "but in wartime the risk of a contractor being unable to remain solvent and to supply goods was recognised, resulting in the Victualling Board suspending contracts and providing its own local management. These managers were agent victuallers who either served afloat with a squadron or on shore at the main ports."2

Artist: Edward Barlow - Port Royal Jamaica Around 1677, Sketch From Barlow's Journal

This list also includes the two Victualling Agents stationed in Jamaica. These men were contracted victuallers rather than Agent Victuallers, similar to those who victualled in the period before 1683. As such, they were not directly paid by the navy to oversee a proper victualling yard. They have been included because the location was central to the English navy in what happens to be one of the two hotbeds of pirate activity during this period (The other being the north-western part of the Indian Ocean.)

Because most of the Agent Victuallers were initially located in England (referred to as the United Kingdom after 1707), they were able to have direct contact with the Victualling Committee. This allowed them to receive their instructions from the victualling and navy boards. The formal instructions that existed at this time were found in the Victualling Instructions.

1 See Janet MacDonald, Feeding Nelsons Navy, 2014, pp. 56-7; 2 John Frederick Day, 'British Admiralty Control and Naval Power in the Indian Ocean (1793-1815)', Vol 1, Doctoral Thesis, University of Exeter, 2012, p. 70 & R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 249

Agent Victualler Instructions and Procedures

The Instructions given to the Victualling Committee were fairly specific, supplying the information that the Agents needed to run their sites. The Victualling Agents themselves are only mentioned a few times in the Instructions, almost as an afterthought. They are essentially recognized as proxies for the Commissioners themselves. Article eight of the 1690 instructions and 1697 instructions (and almost certainly the original 1683 instructions) stated that when navy ships pursers wanted provisions, they were to send their request "to the [Victualling] Commissioners, or their Agents... which Receipt and Order is to be taken up by the said Commissioners, and shall be a sufficient Warrant unto them for issuing the Value thereof unto the Purser"1. The article further expands upon how this was to be done, although it doesn't mention the Agents again, referring only to the Commissioners. The Agent Victuallers got their direction directly from the Committee.

The need for written Victualling Instructions occurred with the establishment of Stephen Bisse as the Agent Victualler at Lisbon, Portugal in January of 1704.

Artist: Peter Mono my - A View of Lisbon (1735)

Because the Victualling Board could not communicate with Bisse in a timely fashion, the Committee felt compelled to give him something to refer to when making daily decisions for his station. Historian Paula Watson describes the instructions issued to Bisse in her doctoral thesis.

There were seventeen clauses, which laid down in detail the allowance of victuals to each seaman, the methods of issuing provisions to her Majesty's ships, and the system of paying and the amount of short allowance money. The agent must keep a strict account of all provisions sent from England, of all provisions bought from abroad, from whom bought and to what ships they had been sent, of all money paid for provisions, and for necessary money and for short allowance and incidents. He was to take vouchers for all of these services. He was to ensure that all provisions he bought or received were first surveyed and he was not to receive them unless they were good. He must take care to issue the oldest victuals for first spending. Any provisions cast by survey [found defective] he was to try to sell. He was to make sure that any wine bought abroad was good and fit for the service. Finally he was directed to correspond regularly with the board, sending the pursers indents. [Adm 7/215]2

Watson notes that these instructions were similar to the instructions given to the Victualling Committee by the Navy Board. In 1705, similar printed instructions were given to newly promoted Agent Victualler John Stucly in Portsmouth. This document recommended

the quantities of cask and provisions to be issued to each ship, the correct preparations of victuals, particularly beef and pork, the marking and gauging of the cask, the amount and methods of paying short allowance money and the purser's necessary and extra necessary money, the procedure to be followed at the receipt into the office of all newly bought goods and stores, returned or decayed provisions, the disposal of decayed provisions and the methods of keeping accounts. The agent was to send to the board a monthly account of the remains in store, a monthly account of all provisions, casks, hoops and bags returned into stores, a weekly account of the progress made in victualling ships under orders at that port, a twice yearly statement of debt, and a half yearly account of the money received from the sale of offal and decayed provisions. He was to keep an account of all money imprested to him and how it was spent. He was to make up the paybooks for the workmen and labourers for each quarter and send them to the board within a month after the end of each quarter.3

Artist: Paul Lacroix

Preparing Ships, From XVIII Siecle Institutions Usages et Costumes France 1700-1789 (1875)

A review of the 1697 Instructions issued by the Navy Board reveals their similarity to those given to the Victualling Committee. At that time, there were 19 clauses, several of which would have been irrelevant to the Agent Victuallers. So the substance of the agents' instructions were probably taken from the instructions to the Victualling Committee, removing those which would not concern them.

Copies of these instructions were sent to the other outport victualling agents and storekeepers in 1706.4 Writing years later, Deputy Secretary to the Navy Thomas Corbett recalled, "'Till the year 1706 ...the Agents ...had not any instructions to guide themselves by nor any Cheque or Comptrol kept on them, which led many (no doubt) into the Temptation of raising themselves Fortunes, at the Expense of the Publick."5

In fact, the golden age of piracy version of the Clerk of the Cheque position in London had been established in 1704. Among his responsibilities were overseeing the Agent Victuallers and Storekeepers.6 Still, as Watson points out, "The issuing of instructions was a step forward in the development of the victualling service. Up to then the agents and storekeepers had been left to their own devices, now they could no longer plead ignorance of their duties to excuse their failures."7

In August of 1710, new, more detailed instructions were issued to those in charge of the naval victualling locations.

Artist: Hendrik Waninghen

Keeping Account Books, From

T Recht gebruyck vant Italiaens

Boeck-Houde (1672)

For the first time instructions were sent to the storekeepers as well as the newly appointed clerks of the cheque. The instructions covered every aspect of the work. Particular emphasis was laid on the three officers [agents, storekeepers and Clerks of the Cheque] checking each other's behaviour and accounts. All three were to be present at the receipt and issue of provisions from the stores. When the agent received orders to victual a ship he was to send his 'warrant to the storekeeper for the receiving as well as issuing all provisions to victual her Majesty's ships for the sea, giving notice thereof to the cheque to the end he may keep an account how the same is complied with.' [ADM 110/5] 8

The last comment was included in an effort to prevent cheating by Victualling Agents as well as ship's officers.

Clerks of the Cheque were established at victualling sites to oversee the quality of the provisions purchased as well as the quantity issued. One of their primary duties was to provide a check on the Victualling Stations' storekeepers. They kept an account of all the provisions received by and issued from the station, including those returned damaged or unused by returning ships. They were to be

Present at the selling of all... decayed provisions, taking care the same be timely disposed of to her Majesty's best advantage and you are to keep an account of the quantity of every specie sold, with the time when, to whom and price sold at, in order to your signing with the agent and storekeeper a particular account of all monies so received to be sent to us [the Admiralty] every half year. You are also with them to sign to the monthly account of decayed provisions which is to be sent us. [Adm 110/5f pp. 41-4, clause 12]9

They worked with the Agent Victuallers while also providing an account of the activities taking place at their station.

Further information on the role of the Agent Victuallers is found in the material gathered by Thomas Corbett in the late 1720s and published in 1731 as the English Navy's Regulations and Instructions. This document focuses on the behavior of officers on navy vessels; with the agents being mentioned in the Purser's Instructions

Artist: Claude-Joseph Vernet - Unloading Ship, Dieppe Harbor (1865)

. For example, Article II of the Purser's Instructions ordered that when a ship was in port being fitted out for a voyage, the purser was to get an official warrant for the provisions needed to victual the men aboard the ship every three days "which Warrant he is to deliver to the Agent for Victualling, and to see that the Ship be duly supplied; and he is to take care, that Not to spend no Part of the Sea Provisions be expended"10. The orders for these special 'petty warrant victuals' explained that while a ship was in port provisions were to be procured every three days because the amount of food needed changed as new sailors were recruited.

The Agent Victuallers are mentioned in the Purser's Instructions in several other places. An order stated that the ship's purser was "not to purchase any Provisions in Places where there is an Agent or Contractor, or when there is a likelihood of [one] coming in their way"11. If a ship was shorted provisions because of a lack of space, this was to be brought to the agent's attention by the purser.12 Any provisions other than cheese that a ship's purser determined to be bad during a voyage had to be returned "to the Agent of the Victualling. The like he is to do, if the Ship be at Sea, and an Agent with Victualling Vessels be in Company."13 Article XXXVI stated that when the ship returned to a Victualling Station, the purser was to return the "Ship’s Provisions, together with the [empty] Cask[s], Iron Hoops, and Biscuit Bags; and the Purser is to send with the said Provisions his Steward, or some careful Person, to see the safe Delivery of them to the Agent, or other Officer appointed to receive them."14 Several of the Agent Victualler's responsibilities in the latter half of the golden age of piracy can be gleaned from these orders.

One of the more confusing aspects of the Agent Victualler's role was how they paid for purchases. They were not given cash nor did they operate on credit. Instead, the navy used the method of 'impresting' to pay for victuals. This was how the Agent Victuallers, contractors, pursers and other warrant officers paid for things they needed. 'Imprests' were "bills of exchange drawn on the Navy Board through naval agents or local merchants, by arrangement with the Admiralty."15 Historian Janet MacDonald explains the process in enlightening detail.

Artist: Thomas Rowlandson

Reviewing the Books, A Merchants Office (1789)

Every time a financial transaction took place, the cost was charged to someone's salary or business account and stayed there until their accounts could be passed. [Checked by naval officials to make sure everything was correct.] When the captain decreed an extra issue of wine for the sick, it was charged to his salary. When an agent victualler abroad made a local purchase and paid for it by a Bill of Exchange, as soon as the Bill had been presented to the Victualling Board and paid, that amount was charged to the agent victualler's salary. When a victualling contractor ...bought supplies with his own money, that amount was the subject of an imprest to his account. The system operated on a 'guilty until proven innocent' basis, and proving your innocence could take many years.16

Once an official had submitted all the required documents (which were required to be original documents) and their account had been examined and passed, the charge against their salary would be released.

The Agent Victualler could have some cash on hand to pay the sailors in port their short allowance money. This was money owed them because ships were put on short rations to conserve the sea victuals. In 1696, the Navy Board mentioned that "When the seamen of his Majesty's ships are at short allowance of all sorts of provisions, 2d. a man a day (or 4/8d. a man a month) hath always been allowed them. But when at whole allowance of drink and short allowance of other provisions, then three halfpence a man a day (or 3/6d. a man a month) hath always been the price, and never more."17

The procedure was mentioned in the letter sent to the House of Commons in 1703 during an investigation of naval procedures. The Victualling Commission wrote them, explaining that

an agent is sent on board some ship attending the fleet, with money, in specie [cash] and credit, to the several ports where they may probably touch; and he pays to each man, there in person to receive it, his short-allowance money monthly. He is strictly enjoined not only to receive and issue the wine, oil, etc., but to have a particular inspection and regard to the quality and goodness of each species [type] of the provisions to be procured abroad, and to follow such orders from time to time as he shall receive from the admiral or commander in chief.18

However, the agents weren't the only ones handing out this money. In May of 1694, the House of

Artist: Michael Dahl - Admiral of the Fleet sir George Rooke (c. 1703-8)

Lords ordered the Victualling Commissioners to "take care to have the short allowance money paid to the seaman" who were stationed at Cadiz and in the Straits of Gibraltar by packet boat.19 There was no official Victualling Agent stationed there at that time and Admiral of the Fleet Edward Russell was credited for the money. However, the next year, Admiral of the Fleet George Rooke complained about

the abuse they [the seamen] are under in the payment of their short allowance money. The Victuallers pretended to pay them but 3l 6d. per month, which I believe is hardly half the present value of what [food] is stopped from them. And what they do receive is yet more short by its being paid in light gold [low carat gold, alloyed with other metals] and other bad money. These are matters I think my duty to offer to your Lordships' consideration for such directions as your wisdom shall think proper.20

This suggests that the money was in the hands of the local agent who was contracted by the navy to victual the fleet there.

1 His Majesty's Stationery Office, Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 12, 1697-1699, 1803, pp. 39; 2 Paula K. Watson, "The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714," University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p. 164-5; 3 Watson, p. 165-6; 4 R.D. Merriman, The Sergison Papers, (Naval Clerk of Acts), 1950, p. 235; 5 Daniel A. Baugh, British Naval Administration in the Age of Walpole, 2015, p. 403; 6 See Watson, p. 149; 7 Watson, p. 165; 8 Watson, pp. 166-7; 9 Watson, pp. 167-8; 10 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea,1st ed, 1731, pp. 113; 11 Regulations and instructions..., p. 120; 12 Regulations and instructions..., p. 114;13 Regulations and instructions..., p. 117; 14 Regulations and instructions..., p. 126; 15 R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 29; 16 Janet MacDonald, Feeding Nelsons Navy, 2014, p. 73; 17 Merriman, The Sergison Papers, p. 252; 18 "Commissioners of the Victualling to a Committee of the House of Commons, December 1703", Cited in Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, p. 270; 19 Her Majesty's Stationary Office, The Manuscripts of the House of Lords, 1693-5, 1900, p. 467-8; 20 Merriman,The Sergison Papers, p. 252

Agent Victuallers And Fraud

Agent Victuallers had a variety of opportunities to cheat the government. Some of this occurred after the fact. Since no rules appear to have been issued to any of the victualling agents before 1704, Agent Victuallers would have had a fairly free hand in running their sites, providing them with such opportunities.

Artist: Paul Lacroix

Making Arrangements to Sail, From XVIII Siecle Institutions

Usages et Costumes France 1700-1789 (1875)

A review of the procedures used previous to the appointment of a new group of Victualling Commissioners in 1703 brought this to light. The Commissioners reported that between April of 1689 and June of 1700, Agent Victuallers had drawn up generic bills of exchange which failed to specify the "quality, quantity, or price, of the provisions bought and furnished by them ...[using generic terms, such] as 'biscuits', 'beer', 'beef', 'pork', 'flour', 'suet', 'wheat', 'malt', 'hops ', 'coals', 'faggots' [wood sticks used for fires], 'pipe-staves', 'hoops', ' cooperage', 'freight', 'cartage', 'wages to butchers, salters, and labourers', 'repairs of buildings', 'contingent charges', etc."1

Since the Victualling Committee had kept no record of their transactions until September of 1699, the outport Agent Victuallers were, "left to themselves, without check on them... [so that] a wonderful and unreasonable latitude was thereby given them; and the said [1703 Victualling] Commissioners... [were] rendered far less able to trace and examine, check, control, and audit such accounts, both in respect of the cash with which they are entrusted and of the stores bought with such cash."2 The 1703 Commissioners said that this poor record-keeping was even more alarming given that "some of the agents themselves have been concerned and interested as dealers in some of the species of provisions ... and become sellers of them, too, directly against the 16th article of the General Instructions."3 Article 16, which appears in both the Victualling Instructions of 1690 and the Victualling Instructions of 1697, warned that agents who sold goods to the navy had to answer for such behavior4, although no action appeared to have been taken according to their review.

The Victualling Commissioners further complained that the only record some of the agents kept during the period were their quarterly reports. Even in many of those reports,

no balance hath been kept of the wheat, malt, hops, salt, and coals, received or expended, so that it can neither be discovered how those provisions are accounted for, nor whether the proper quantities of malt and hops were put into such quantities of beer as brewed for the Fleet; neither, consequently, whether such beer was of sufficient strength; with the like of the biscuit baked there.5

These reports were sometimes sent to the commission long after Agent Victualler had purchased the provisions, other times after a purser who had been issued goods had already been approved by the previous committee and on occasion even after the agent himself had died, "which hath subjected the Crown to manifold inconveniences."6 Historian Paula Watson comments, "No attempt had been made to give each commissioner a section of the service to supervise, whereby many abuses might have been eliminated."7

Several safeguards were put into place in an effort to prevent such fraud. Once the 1703 Committee had finished gong through their accounts and attempting to settle the previous 'course' of payments, they appointed a Clerk of the Cheque in London in an effort to oversee outport Storekeepers and Agent Victuallers. Two years later, instructions were issued to every Agent explaining his duties and outlining proper record keeping. In 1710, new

Ah, the Navy and Their Pork...

procedures put in place by the Victualling Committee stationed a Clerk of the Cheque at each Victualling Location in an added attempt to prevent cheating by each yard's agent and storekeeper. That year also saw the division of tasks among the committee members so that they could more closely oversee individual operations.

Agent Victuallers were also responsible for handling fraud occurring within their yards. In October of 1709, Plymouth agent John Stucly responded to an anonymous letter of complaint sent to Northern Secretary of State Henry Boyle. Two complaints were made: one about the practices of the Plymouth yard in accepting pork and the other about the a bribe paid to the person weighing the pieces of pork. With regard to the practices at Plymouth, Stucly explained that accusations of ill practices in accepting hogs were "so far false, to my own knowledge, that very many hogs have been, from time to time, rejected, though upwards of a hundredweight, for want of being properly fed or proving to be gale [?gelt] pigs. And great numbers, as may be seen by all our bills, received, though under a hundredweight, when found to be fat and well fed, with the abatement of 2s. per cwt."8 With regard to the other complaint of bribery on the part of the person weighing the hogs, Stucly said he couldn't find any evidence of it and would need more information to investigate it further.

1 "Commissioners of the Victualling to Secretary of the Lord Treasurer" 30th October 1703, R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 263; 2 "Commissioners of the Victualling to Secretary of the Lord Treasurer", 30th October 1703, Merriman, p. 263-4; 3 "Commissioners of the Victualling to Secretary of the Lord Treasurer - 30th October 1703", p. 264; 4 His Majesty's Stationery Office, Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 12, 1697-1699, 1803, p. 399; 5 "Commissioners of the Victualling to Secretary of the Lord Treasurer - 30th October 1703", Merriman, p. 264-5; 6 "Commissioners of the Victualling to Secretary of the Lord Treasurer", 30th October 1703, Merriman, p. 264; 7 Paula K. Watson, "The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714," University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p. 121-2; "John Stucley, Victualling Agent at Plymouth, to the Victualling Board," 4th October 1709, Merriman, p. 291