Organizing Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Next>>

Organization of Ship's Food In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 2

Naval Victualling Procedures Overview

(Those wishing to skip past the discussion of naval victualling procedures can jump ahead to page on Pursers.)

"Whereas those Brave Worthy Commanders, who Victual extraordinary well, and take great care of their men, do come home well, and their men love them, and I love them also for their Honesty and love to the Seamen." (William Hodges, Humble proposals for the relief, encouragement, security and happiness of the loyal, courageous seamen of England, 1695, p. 44)"

Artist: John Cleveley the Younger - Launch of HMS Alexander at Deptford (1778)

A discussion of the food served to English navy sailors must begin with a look at the growth of their victualling procedures. Of the five types of sailors under consideration, food procurement for the navy was the most complex, due to the bureaucracy that grew around it during this period. While the organization depended on officers such as quartermasters and cooks to oversee food distribution and preparation like every other type of English sailor, they also had a unique officer involved in food procurement: the naval victualler. Other legal voyages used private victuallers to supply their food, but the navy had a structured system which incorporated navy men for this role, particularly in England, Scotland and Ireland during the Golden Age of Piracy (GAoP).

Victualling an organization as large as the English navy was complex. The provisioning system established a variety of locations to provide food for English naval sailors. These locations depended largely on which enemy the English was at war with as well as where English merchant vessels were sailing (for whom the navy provided escorts to protect them) when there weren't.

A Sampling of Navy Designated Victualling Stations Between 1665-1748,

Image Artist: Francis Holman - Blackwall Yard from the Thames (1784)

The system focused on London because the cosmopolitan marketplace there made getting supplies easier. A variety of 'outports' were established in cities both in England and abroad to support naval vessels. However, the majority of the outport food supplies were shipped from London. Some outport victualling agents did purchase supplies locally when it made sense.

Three English outports were consistently used between 1665 and 1748: Portsmouth, Dover and Plymouth. The rest of the English outports flourished, withered or even disappeared based on how the English were fighting. In addition to these were foreign outports, only two of which were consistently used during the time period: Kinsale, Ireland and Gibraltar. While not used before the GAoP, Gibraltar was often used during it. In addition, once the English established a foothold in Port Mahon, Spain, it was active for much of the period. Several other foreign outports were established as the English needed them as seen in the chart at right, although they were not in constant use during the period A more detailed history of victualling at the important sites in this chart can be found in the article on English Royal Navy Victualling.

This section looks at the history of naval victualling procedures, broadly dividing it into two periods

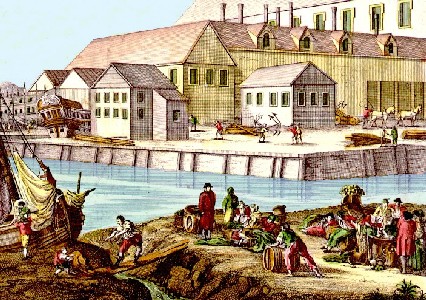

Artist: Balthasar Friedric Leizelt - Preparing and Loading Stores (1770s)

which are further subdivided by governance. The first broad period briefly looks at victualling before the creation of the Victualling Board. It begins with the system employed from at least the 1500s to 1648, where the navy relied primarily on contracts, a system which was likely in use by large, on-going merchant shipping concerns during the GAoP. The next part examines changes made by the republic (commonwealth) between 1648 and 1660. The third part discusses efforts related to victualling established by Samuel Pepys in the 1660s and early 1670s.

The second broad period examines the system under the Navy's Victualling Board. It starts with a look at the establishment of the Victualling Board and accompanying rules created in 1683. This is followed by a discussion of the early efforts by the board during the periods ruled by Charles II, James II, Mary II and William III - 1684 to 1701, focusing particularly on challenges the board faced during the War of the League of Augsberg (1689-97). Next, victualling by the board under Queen Anne during the War of Spanish Succession is reviewed (1702-1714), followed by a look at victualling during the peace under George I between 1714 and 1725. This section closes with a brief look at a some of the rules codified in 1731 related to victualling.

Early Period Naval Victualling Procedures (1500s - 1648)

Prior to the republic, food was supplied to the navy by contracted vendors, with little oversight.1 These vendors were paid with "ready money" i.e.. cash,2 resulting in a system marked by food quality issues and abuses. In the first half of the 16th century (1520-47), victualling was performed by special commissioners subject to purveyance - vendors selling to the navy at prices set by the king - and "was open to considerable abuse... [offering] many opportunities for sharp practice."3

Artist: Hans Holbein the Younger - Henry VIII (1540)

For example, during an English engagement against Scotland in 1544, the leaders wrote the king, "yt appereth unto us, your mejeste hath not byn a litell deceyved [in 'thorder' of the victuals]...", explaining that 1) the 'pipes' [casks] of beef contained fewer pieces than specified many of the individual pieces of beef being underweight, 2) there was less 'bread' (biscuit) than what was paid for with "a grete parte of that is here, ys so mouldye and Ill husbanded in the baking, that we assure your highnes at this present it is no mans meate [food]"4.

In 1547, Edward Baeshe was selected from a number of victuallers by the navy to work with Richard Watts as 'surveyors of victuals within the city of London.' This gave them the ability to oversee naval victualling within the city, pressing sailors, workers and ships into service. In June of 1550, Baeshe was appointed General Surveyor of the Victuals for the Seas by Letters Patent.5 Historian Michael Oppenheim suggests that was implemented by King Henry VIII based on his "clear perception of the needs of the growing Navy, and his liking for systematic and responsible management"6. Baeshe's accounts were kept by the Lord Treasurer until 1557 when he was ordered to keep his own accounts, although he still received his money from the Lord Treasurer until 1564 'in prest'. His agents and assistants in each county purchased food for the navy under the system of purveyance. In 1560, he was provided with a victualling headquarters at Tower Hill along with several storehouses.7

The purveyance system was abandoned in 1565 and Baeshe was given a contract under which he was given 4-1/2d. per day per man in harbor, and 5d. a day for each man at sea. The menu specified in this contract was very much like the one still in use during the golden age of piracy. However, Baeshe had trouble purchasing provisions at these rates, resulting in the contract being modified by the addition of 1d. per day per man both in harbor and at sea. Without the price specifications found in purveyance, Baeshe had to buy provisions in the open market where prices varied while the amount he was paid for each man did not. So that his large purchases didn't drive up the cost of victuals in the marketplace, he had to spread his purchases out over various vendors and locations.8 James Quarles joined Baeshe in handling the navy contract in 1582. When Baeshe died in 1587, position was assumed by Quarles.

English Fireships Attacking Spanish Armada in 1588 (c. 1590)

The food supplied to the English navy was not inspected at all during this time and the quality of provision reflected this. Once the Navy Commissioners had placed their order, victualling contractors Allen Apsley and Sampson Darrell appear "to have sent what provisions they pleased on board the ships, quite independently of any supervision or of any way of calling them to account, [resulting in] supplies infinitely more deadly to our men than the steel and lead of the enemy."9 The navy was rife with complaints about the quality of the food during this period.10 It is also notable that, unlike later periods, the food supplied at this time to navy sailors was listed only as beer, bread and meat.11

Food quality and supply under the early victualler's depended on the honesty of the man in charge of victualling. Some efforts were occasionally made to improve naval provision quality. In November of 1635 John Crane, then the 'Chief Clerk of the Kitchen', was appointed Surveyor of Marine Victuals just in time to supply the 1636 Fleet. He was to supply daily victuals at the rate of eight pence halfpenny a man per day at sea, and seven pence halfpenny in harbour. His title suggests some responsibility for quality. However, the amount he was given to purchase victuals proved inadequate based on then current food prices. "He found that during 1636 and 1637 he had lost a penny three farthings a month on each man, and anticipated a further loss of as much as 3s 4-3/4d a head, per month, in 1638. He entreated an immediate release from his bargain, or he would be ruined, and he had thirteen children."12 It is notable that complaints about the food among the sailors decreased during this brief period.

1 Paula K. Watson, "The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714," University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p. 68; 2 Watson, p. 149; 3 David Loades, The Tudor Navy, An Administrative, political and military history, 1992, p. 84; 4 The Hamilton Papers, Vol II, Joseph Bain, ed., 1892, p. 346; 5 Loades, p. 150 & Michael Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, 1896, p. 103; 6 Oppenheim, p. 103; 7 Loades, p. 203; 8 Loades, p. 205-6;9 Oppenheim, p. 222; 10 Oppenheim, p. 223; 11 Oppenheim, p. 82; 12 Oppenheim, p. 238

Naval Victualling Procedures During the Commonwealth (1649 - 1660)

Following the Second English Civil War, England became a republic under 'An Act declaring England to be a Commonwealth' in 1648.

Artist: Samuel Cooper - Oliver Cromwell, Unfinished Miniature (17th Century)

This period is typically referred to as the Commonwealth. The years 1653-1659, when Oliver Cromwell was made Lord Protector, are often called 'the Protectorate' or 'Interregnum'. For simplicity, this article uses the term 'Commonwealth' for the entirety of the period where the monarchy was deposed in England (1648-1660).

The quality of the food supplied to the men and the honesty of the victualling agents both steadily deteriorated during the Commonwealth.1 Historian Michael Oppenheim presents several examples of victualling agents behaving with hostility to complaints of the navy sailors. Members of the crew of Fourth Rate Frigate Tyger showed the victualling agent at Harwich "their bread and beer which, their captain agreed, was not fit for food. The agent sent for the baker and brewer, and the former told the men that they were 'mutinous rogues,' that it was good enough for their betters, and next time should be worse." Another victualler told the men of the fourth rate Maidstone some time after 1653 that "the more they complained the worse they should have. This coming to the ears of the men, some of the Maidstone's crew went ashore and wrecked his house."2

Artist: Daniel Schellinks - HMS Tiger taking the Schakerloo at Cadiz (1675)

On top of the victuals being bad, there weren't enough of them. These issues continued to plague the navy during the entirety of the Commonwealth. In March of 1660, the captain of the fifth rate Bryer told the Admiralty Committee "that his officers are compelled to buy their own food, and his men to forage for themselves on shore; the other, from the victualling agent at Hull, acknowledges the receipt of their warrant to furnish the Bryer and Forester, but, before acting on it, desires to know how he is to be paid."3

In September of 1660, naval victualler Denis Gauden was made 'surveyor-general of all victuals to be provided for his Majesty's ships and maritime causes,' being paid 50£. a year for his trouble. Although he was solely responsible for victualling the navy, they failed to pay him in a timely fashion. When the second Dutch War began in 1665, he couldn't meet the sudden increase in demand. As a result, "the victuals, though on the whole good in quality, were deficient in quantity, and when Gauden was remonstrated with he could always reply... that it was impossible for him to do better as long as the government failed to keep their part of the contract, and to make payments on account at the stipulated times."4 Foreshadowing the near future, an attempt to solve this problem in August of 1655 by creating a government-run victualling organization. Unfortunately, it was abolished at the beginning of the Restoration in 1660 before the results could be evaluated.5

1 Michael Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, 1896, p. 324; 2 Oppenheim, p. 327; 3 Oppenheim, p. 328; 4 Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, Vol. I, JR Tanner ed, 1903, p. 152; 5 J. R. Tanner, The Victualling Instructions of 1697", The Mariner's Mirror, Vol 1, Issue 2, 1911, p. 51

Naval Victualling Procedures Under Samuel Pepys (1660-1679/83)

"Englishmen, and more especially seamen, love their bellies above anything else, and therefore it must always be remembered in the management of the victualling of the Navy that to make any abatement from them in the quantity or agreeableness of the victuals is to discourage and provoke them in the tenderest point, and will sooner render them disgusted with the King's service than any one other hardship that can be put upon them." (Samuel Pepys, Samuel Pepys Naval Minutes, J. R. Tanner, ed, 1926, p. 250)

Artist: John Hayls - Samuel Pepys (1666)

This period began with the recreation of the position of Navy Clerk in instructions issued on January 28, 1662 by the Lord High Admiral James II. Samuel Pepys was appointed to the position, one he held until 1673. He provided the link between the king and the navy administration, being responsible for advising the Navy Board of the "present market price of all manner of petty provisions"1. Pepys was a strong advocate for the navy, working to build the fleet, establish order in their policies and keep accurate records.2 However, any advice Pepys gave the Navy Board was offset by a lack of funds, which continued to plague effective navy purchasing for several years. As late as January of 1666, Navy Commissioner in Portsmouth Thomas Middleton wrote that "All men distrust London pay" in reference to problems the navy found when trying to arrange for victualling suppliers.3

The system at this time relied on Denis Gaudin as an individual victualler. Due to Gauden's money problems, caused primarily by the navy's slow payments to him, he failed to supply enough victuals to the navy. In an effort to improve the situation, Gauden, suggested that "a surveyor of victuals should be appointed at the king's charge in each port, with power to examine books, contracts, &c., and instructed to report weekly to a general officer in London."4 This was approved by the king in early October of 1665. Pepys suggested he assume the role of surveyor general which enacted on October 27th at a salary of £300 a year.

Pepys wrote in July of 1666 that victualling was "much in a better condition than it was the last yeare"5. There were still complaints about the food, however. Fleet officers Prince Rupert and the

Artist: Sir Godfrey Kneller - Duke of York, James II (1684)

Duke of Albemarle sent a letter to the king in August of 1666 from the front lines which complained "of the want of supplies, in spite of repeated importunities. The demands are answered by accounts from Mr. Pepys of what has been sent to the fleet, which will not satisfy the ships, unless the provisions could be found. [They] Hope to be credited as to their wants."6 Pepys called it "a most scurvy letter... [and accused the victualling officials of] neglecting them and the King’s service, and this in very plain and sharp and menacing terms."7 Still, "Pepys was much pleased with his arrangements, and was complimented by the Duke of York (James II), and it is certainly the case that the State Papers for the year 1666 do not contain as many complaints against the victuallers as those for 1665."8

The Navy does not appear to have shared this rosy view, however. The position of Surveyor General was eliminated at the end of the Second Dutch War in 1667, leading to "further consideration of the possibility of a complete change of method, [with] some thinking that the victualling could be better managed by a commission. It was eventually decided to open it to a new contract."9

Unfortunately, they didn't allow enough time for competing victuallers to quote the job, making it impossible for them to supply provisions in a timely fashion. Victualler Gauden had used all his credit with his vendors and rather than bid the job, he submitted a bill for what the navy owed him: £176,725. 6s. 5d.10 "The result of the negotiations was that Gauden, to whom the government was so deeply in debt, was allowed by an Order in Council of September, 1668, again to undertake the victualling at 6d. a day per man harbour victuals and 8d. sea victuals, with 8 3/4d. for ships going 27 degrees southward. Being so deeply in debt to him, the navy commissioners decided to continue working with Gauden with the proviso that he be associated with two people appointed by the king to take over in the event of Gauden's death.11

Pepys suggested the Gauden's sons be brought into the business. It was decided instead to appoint two outsiders to serve in this capacity. The king was thus convinced "to the committing to a

Artist: Willem van de Velde the Younger

Battle Of Texel in The Third Dutch War - 1673 (1687)

partnership of three [men specified] the performance of that contract which till then had with much hazard been still lodged in the hands of one" in 1669.12 However, the navy didn't address their lack of payment to Gauden, which made him an ineffective victualler. He again complained about problems of payment for victualling in 1671.13

With the outbreak of the Third Dutch War in 1672, upscaling the fleet increased the need for good navy victualling at a time when payment to the victualler was so bad he had to rely on his own money and credit to provide their food. Those fighting either didn't know this or ignored it. "Prince Rupert was so annoyed that he declared that he would never thrive at sea till some [of the victuallers] were hanged on land; and a little later expressed the opinion that the only way to deal with the Victuallers would be to send one of them on shipboard, there to stay in what condition his Majesty shall think fitting, till they have thoroughly victualled the fleet."14

During the war, James II resigned all his government posts in 1673 including his position as Lord High Admiral to protest of the Test Act which would have required him to renounce his Catholicism to remain in the government. To bolster the navy, Charles II appointed Pepys Parliamentary and Financial Secretary to the Admiralty in June, a post with many responsibilities including the purchase of victualling stores. Unfortunately, the central problem - the navy's payment of the victualler - wasn't fixed even after the war had ceased in 1674, limiting Pepys' ability to fix the problem. "Consequently there were frequent shortages and failures. The contractors also claimed the right to give the [ship's] pursers money instead of some part of the victuals."16

One of the most helpful things Pepys did was create a new contract with three different victuallers in 1677. This contract is often suggested to provide the definitive map for navy sea victuals, a plan which remained in place for well over a century. In fact, it draws heavily upon previous victualling contracts, such as the 1636 contract with victualler John Crane.15 (See the section on Navy Sea Victuals for a detailed look at food rations spelled out in the various contracts leading up to the 1677 contract.) It contained a variety of important rules and standards for how food was to be purchased, loaded, maintained, recorded, dispensed and returned which carried forward long afterwards.

The victuallers' inability to adequately supply the navy continued to deteriorate. In late March, 1679, Pepys said "I know not how possibly to lament enough the wretched state his Majesty's service must be in while it lies under this uncertainty of being

Artist: Godfrey Kneller - Samuel Pepys (1689)

supplied with stores and provisions' at this port [Portsmouth], and to admit at the same time the yet greater uncertainty of ...meeting with any despatch at Plymouth."17 Pepys mentions scheduling a meeting with the victuallers to discuss this, but doesn't record the results.

Looking back on his time organizing the navy's victualling procedures some time later in 1680, Pepys opined,

Bad payment of the victuallers and other contractors has always been made use of and prevailed in excuse for every failure of theirs wherein the service suffered, and yet has intituled [entitled] them to get payment afterwards when those failures and the consequences were slipt out of mind, or at least might be extenuated, or the heads of the King's officers full of other business or otherwise tempted not to make the most of them, and in the mean time under those necessities of the King's service anything is accepted instead of good, because the service must be supplied and better was not to be had.18

While Pepys' efforts to improve the victualling system had some effect, the problem of poor payment of the navy's victuallers resulted in the inevitable failure of his system. As a result, the Surveyor-General of Victualling position was eliminated in 1683 and the Victualling Commission was created to replace it.

1 William Monson, The Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson, Vol. IV, M. Oppenheim, ed., 1913, p. 14; 2 Paula K. Watson, "The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714," University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p. 31; 3 J. R. Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy from the Restoration to the Revolution", The English Historical Review, Vol. XII (1897), p. 29; 4 Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy...", The English Historical Review, Vol. XII (1897), p. 37-8; 5 Samuel Pepys, Pepys Diary, July 26, 1666; 6 'Aug. 27. Royal Charles, Sole Bay' CSPS Domestic, p. 71; 7 Pepys, August 28, 1666; 8 Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, Vol. I, J. R. Tanner ed, 1903, p. 154; 9 Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy...", Vol. XII (1897), p. 38; 10 Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy...", Vol. XII (1897), p. 38; 11 Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy...", Vol. XII (1897), p. 39; 12 Watson, p. 31; 13 CSP Domestic, January to November, 1671, "Jan 27/Feb. 6, Sir Thos. Clutterbuck to Navy Commissioners", p. 53 & Naval Manuscripts..., p. 156; 14 J. R. Tanner, Samuel Pepys and the Royal Navy, 1920, p. 59-60; 15 CSP Domestic, 1636-7, 1867, p. 452-3; 16 Watson, p. 31; 17 J.R. Tanner, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 180; 18 Samuel Pepys, Samuel Pepys Naval Minutes, J.R. Tanner, ed, 1926, p. 88