Organizing Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Next>>

Organization of Ship's Food In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 12

Officers In Charge of Food - Stewards

"STEWARD of a Ship, is he that receives all the Victuals from the Purser; and he is to see it well Stow'd in the Hold: In his Custody are all Things of that nature belonging to the Ship's use. He is to look after the Bread, and to distribute out the several

Artist: Gabriel Bray

The Steward of the HMS Pallas Weighing a Piece of Beef,

Probably at Portsmouth (1774)

Messes of Victuals in the Ship. He has an Appartment for himself in the Hold, call'd the Steward-Room: And he has usually a Mate under him." (Sieur Guillet, The Gentleman's Dictionary, 1705, not paginated)

Ship's stewards were the earliest recorded officers to specialize in the management of food on ships. As Sieur Guillet explained, their primary responsibility was to stow and keep track of the sailor's food and to issue it to the sailor's messes (typically groups of four to six men on English vessels) and it is this aspect of the job that is most common to the different types of sailors. However, the steward also could function as the purser's mate, being able to take on any task for which the purser was responsible. This was particularly true in ships whose crews were so small that they didn't need a purser. By the golden age of piracy, stewards are mentioned as being appointed for every type of ship under study here including some pirate ships. (It should be noted that there were also captain's stewards on some ships in later periods who managed the food for those who ate with the captain, but not the rest of the crew. However, we will only speak here about ship's stewards, who managed the food for everyone else.)

This section looks in some detail at the role of the ship's steward, beginning with an overview of their early history on English ships, briefly discussing their role up until the the end of the Interregnum (around 1660). It then takes a more detailed look at stewards mentioned in the period accounts under study from 1660 through the end of the golden age of piracy. The steward's location and pay on navy vessels is then briefly discussed. Because they were in positions similar to ship's pursers, stewards sometimes succumbed to the opportunity to cheat the system. However, not being high-ranking officers, stewards were also the men most likely to report cheating by pursers and other crimes committed by the men on the ship.

Early History of Stewards and Their Duties on Ships

Artist: Hieronymus Bosch - Ship of Fools (c. 1490-1501)

"Steward, felow! A pot of bere!

Ye shall have, sir, with good chere,

Anon alle of the best.

...

Steward! cover the boorde anone

And set bred and salt therone,

And tary nat to long!"

(The stations of Rome and The pilgrims' sea voyage, F.J. Furnivall, ed., 1867, pp. 38-9)

The term 'steward' as it applied to overseeing the food on a ship dates at least to the mid-fifteenth century as mentioned in the above poem, which was originally written during the reign of Henry VI. The term was almost certainly in use before that time.1 The officers assigned to Henry VIII's navy ship Henry Grace a Dieu included a purser and steward.2 During the mid-sixteenth century, there are records of stewards on merchant vessels keeping books accounting for the food consumed along with who had left or died during the voyage.3 Records from that time also mention stewards having a specific room on a vessel.4 The navy treasurer's quarter books contain records of payment to a variety of navy stewards from around the same period.5

In orders issued to the Surveyor of Marine Victuals in April of 1565, it was noted that officers "of the Marine Affairs do give from time to time strait charge [strict commands] to the pursers and stewards to preserve the cask and biscuit bags, and to render back the same so nigh as they can, having reasonable allowance by the said E.B. [Edward Bashe, the Surveyor] for water cask and 4d for the drawage [drayage - the cost of transport] of every tun of cask as they now have."6 Here we see the ship's steward being linked to the purser's duties in a naval order, indicating that they sometimes assumed responsibility for the same tasks.

An English East India Company Logo

When the East India Company established their 'lawes or standing orders,' stewards were included among the officers described, although their duties are rather vague. They were to give the ship's master receipts for all their equipment, "that they may be accomptable for the same"7. They were to "give their diligent Attendance aboard Ship from time to time, to receive and take charge of all the Provisions, Victuals and Stores for the Voyage... and to give Accompt of the same [via a receipt] to the Purcers or their Mates"8.

For the navy, William Monson and Nathaniel Boteler described the duties of the steward in the early 17th century, just as they had done for the duties of pursers in the Navy. With regard to the steward and his mate, Monson explained:

His office is to be the purser's deputy, chosen by him, and keeps always in the hold to deliver the victuals to the cook, who is trusted to retail [dole out] the victuals in meet [proper] proportions, and is only accountable to the purser though he has some allowance from the Victualler for well husbanding and keeping the provisions from waste or putrefaction. He must not suffer banqueting [feasting] or disorder in his room but keep it clean and sweet; and, as occasion shall serve, cause the quartermasters to rummage for the better coming to his victuals.9

While Boteler covers many of the same responsibilities of the role, he provides a bit more color, mentioning some interesting differences from Monson's description.

Artist: Cornelus de Wael

Harbour Scene with Sailors on a Beach (1645)

In addition to receiving and stowing the victuals, Boteler says the steward was "to take into his Custody all the Candles; and all things of that nature belonging to the Ships use to look diligently

to the Bread in the Bread-room, and to share out the proportions of all the several Messes in the Ship"10. His mention of supplying candles and other non-food 'necessary items' are notable as this had become a significant part of the purser's responsibility. He also places the bread room of the ship in the steward's care. Bread was kept in a separate room on large navy ships which was specially built to prevent the bread from becoming damp.11 'Wet' food items, such as casks of meat and butter and those not as susceptible to moisture such as peas and oatmeal, were kept in the steward's room.

Unlike Monson, Boteler opines that although the steward seems on the surface to be an assistant to the purser, he also served as a useful check on the purser via his record-keeping of foods both consumed and stored in his rooms.11 This duty was to sometimes prove most useful to the navy as we shall later see. With this in mind, Boteler says that the steward should check to be sure that the 'full proportion' of victuals were brought aboard, validating the purser's report.12

It was likely with this in mind that the navy commissioners recommended "that bonds should be required [on pursers], that stewards should be employed for the victualling, that pursers should in future sail as clerks of the check, with limited powers, and that all their papers should be countersigned by the captain."13. This was implemented in 1653 with the intent that the stewards and purser/clerks of the check would serve in verification of one another in an effort to prevent fraud. However, "the two had every incentive to co-operate in keeping up a mutually profitable

Artist: Peter Lely - Sir Thomas Allin (1665)

system, and the Protectorate Navy had reverted to the former practice."14 As a result, pursers were given their old positions back.

Historian J. R. Tanner suggests "the abandonment of this method may have been that the stewards received money from the victuallers in lieu of a part of the victuals and then deserted with it."15 While victuallers advancing money to the pursers had been a problem before this system was put in place, he doesn't offer supporting for the notion that the stewards were doing the pursers one better by leaving their ships outright with the cash.

Stewards are mentioned in a few of career navy officer Thomas Allin's journals, providing some insight into their role. The first mention comes from February, 1662 when Allin was captain of the 3rd rate Plymouth. The men were complaining about the size of the pieces of salt beef they had been served, which Allin dutifully notes were indeed less that the weight required by the victualling contract, as "weighed by the Steward, our Lieutenant and Master."16 The second mention is from July, 1665 when Allin was Vice-Admiral and commanding officer of the 2nd rate Old James. Here, he mentions in passing that he "sent Stephen Porter ashore with the steward to fetch candle and wood and other necessaries."17 Once again we find the steward overseeing the loading of 'necessaries' for the purser.

1 "steward (n.)", etymonline.com, gathered 9/7/21 & The stations of Rome and The pilgrims' sea voyage, F.J. Furnivall, ed., 1867, p. 38; 2 Michael Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, 1896, p. 75; 3 (1553) Richard Haklyut, The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation, 1599, pp. 228, 4 (1562, Minion, ) Haklyut. p. 55; 5 From some of many examples found in the Navy Treasurer's Quarter Book between 1562 and 1663 see Elizbethan Naval Administration, CS Knighton and David Loads, eds, 2013, pp. 56, 79, 82 & 117-25; 6 Elizbethan Naval Administration, p. 598; 7 East India Company (EIC), The lawes or standing orders of the East India Company, 1621, p. 47; 8 EIC, p. 49; 9 William Monson, The Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson, Vol. IV, M. Oppenheim, ed., 1913, p. 60; 10 Nathaniel Boteler, Colloquia maritima or Sea Dialogues, 1688, p. 19-20; 11 For this reason, "The bread room was, according to an order of 1686, to be double lined with dry seasoned slit deals." - Brian Laverly, The Arming and Fiting of English Ships of War, 1600-1815, 1987, p. 189; 12 Boteler, p. 21; 13 Michael Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, 1896, p. 356; 14 N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, 2006, p. 105-6; 15 J. R. Tanner, 'General Introduction,' A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 163-4; 16 The Journals of Sir Thomas Allin, 1660-1678, Volume I, R. C. Anderson, ed., 1660-1678, Vol 79, 1939, p. 69; 17 Journals of Sir Thomas Allin, p. 240

Stewards and Their Duties During the Golden Age of Piracy

As noted, all the different types of sailors under consideration here made use of stewards. Even the late seventeenth century buccaneers employed them. Surgeon Alexandre Exquemelin notes in his accounts of their exploits: "Here [aboard their ship] they allow, twice a day, every one as much as he can eat, without Weight or measure; nor does the steward of the vessel give any more

Artist: Nicolas Ozanne

The Port of Bordeaux, Seen from the Wheat Dock (1776)

flesh, or any thing else, to the captain, than to the meanest mariner."1 However, the bulk of the records of ship's stewards during this period come from naval, merchant, privateer and pirate accounts.

Unlike the pursers, whose duties the Navy modified in attempt to prevent them from cheating the system, the steward's duties appear to have remained mostly the same as they were in earlier periods. The 1677 Victualler's Contract mentions the steward several times, although always as an alternative to the purser. For example, it states that either the purser or steward is to sign the indent (purchase agreement) for the necessary money used to purchase items such as "wood, candles, dishes, cans, lanterns, spoons, and other necessaries", the money for drawage [drayage] of beer and other, similar funds.2 Either the purser or steward was also to provide receipts for victuals received.3 Surgeon general of the navy James Pearse implemented a policy around this time preventing sick men from being sent ashore "from any ship without a certificate signed by the captain and officers, 'whereof the purser or steward is required to be one,' in order that his allowance [food and pay] on board might be stopped"4.

Curiously, stewards do not appear as an alternative to the purser in either the 1690 or 1697 Victualling Instructions. However, they reappear in the 1731 Instructions relating to His Majesties service at sea, which gathered various regulations created in the previous 40 years. Here, they are again noted as an alternative to the purser in two situations. The first was when attesting that any provisions disposed of were truly bad5 and the second was verifying that provisions supplied to a ship truly fell short of the amount required.6 Still, for the most part, the information we have about the steward's role and behavior on navy vessels is primarily found in the early 17th century writings of Monson and Boteler discussed in the previous section.

Several merchant ship accounts feature stewards.

Artist: Hendrick Cornelisz Vromm

Roundhouse Door (Yellow Circle), From A Castle with a Dutch Ship Sailing Nearby (1626)

The first comes from accounts of a Mutiny in 1697 aboard the merchant Adventure commanded by Thomas Gullock. In defending captain Gullock's treatment of the men, Surgeon Samuel Nixon notes that the captain gave the sailors on watch drams (of liquor) when their shift ended, "never letting them go to their Hamocks wet without a Dram, to be sure of which he did not suffer the Steward to give it them below, but constantly his own Servant at his Round house door."7 From this, the steward's presence on the ship and his duty in doling out the normal provisions can be inferred.

Another account mentioning a merchant vessel steward is found in the captain's account of slaver Henry, in 1721.8 In addition, it was shown that the East India Company had stewards on their ships as early as 1621. Although the company had undergone several changes in their management structure by the golden age of piracy, the Rawlinson manuscripts (C.966) include an account of the East Indiaman Colchester which sailed in 1703 with a crew of 89 and had aboard a cook, a steward, a captain's steward with two assistants and a purser.9

Thomas Bowrey's records of the merchant Mary Galley are quite detailed, providing some insight into the steward's role on this vessel. In a letter sent to some of the officers of the vessel on October 19, 1704, Bowrey says,

Artist: Simon Fokke

Keeping Records, Intérieur d'un coche d'eau (1760)

I would have you Buy the Steward a Book for him to keep a Daily account of the Expence of all sort of Stores under his Charge and of all fresh Provissions received and how Expended, which account [I] would have brought in to you and Examined weekly, and signed by all in Comission as Supra Cargoes [supercargos - representatives of the owners], which account [is] to be delivered to the Owners at your returne to England.10

Another letter sent to some of the ship's officers on November 16th, 1704 warns the them not to spend more than the £30 the owners allowed Captain Joseph Tolson for his table, explaining that they "would have an exact account kept [of the common provisions that are] expended every day by the steward, and a particular account of Expences to be examined and signed by you all three [the captain, supercargo and chief mate] weekly"11. Bowrey held shares in several merchant ships around the golden age of piracy, so it is likely that this provides a reasonable overview of the sorts of things a ship's steward on a merchant vessel would be expected to record.

At least one privateering voyage had stewards on the ships. Woodes Rogers' Duke began their voyage in 1708 to South America with John Finch as the ship's steward.12 Little is said of Finch's duties in Rogers' account, although the locked room containing bread and sugar on the ship was broken into in November of 1709, something Rogers blamed on Finch. However, Finch "told me he lay next the Door, with the Key fastness to his Privy Parts, because he had it once stoln out of his pocket"13. That's a level of dedication not found in other accounts of ship's stewards. The steward was clearly an important role on this voyage; even the prize ship Batchelor, taken by Rogers' privateers in December of 1709, felt need to appointed Denis Reading to the role.14

Artist: James Thornhill - William Kidd (18th c.)

Two pirate accounts mention stewards on pirate ships. The first is mentioned by Benjamin Franks in his testimony against William Kidd. After leaving New York on their 'pirate hunting' journey, Kidd's crew encountered a Portuguese ship in September of 1696. Franks explains that the Portuguese captain presented Kidd with a roll of Brazil tobacco and sugar, "in lieu of which Captain Kid sent him a Cheshire Cheese and a Barrell of White Bisket, but through mistake of the Steward the Barrell thought to be Bisket proved to be Cutt and Dry Tobacca."15

The other account is a little less certain, concerning captain George Roberts, something widely believed to be fictional, based on facts from around the period. In this account, Roberts was captured by Edward Low's pirates in 1722 who took most of his crew "on Board of them, not once so much as asking them whether they would Enter with them, only demanding their Names, which the Steward writ down in their Roll Book."16 Since the steward of a ship was often charged with keeping records of what the crew on a ship joined, left and ate, it would make some sense that he would have to make sure to keep an record of any newly 'recruited' crew on a pirate ship. However, it would be a little unusual for pirates to be concerned with accurate record-keeping, particularly since such things could be used in testimony against captured pirates. The same account later notes that the pirate ship's steward was one of four officers who actually slept in a hammock or bed, with all the other pirates "kennelling like Hounds on Deck, or where they could."17

1 Alexandre Exquemelin, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 51; 2 J. R. Tanner, 'General Introduction,' A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 168; 3 Tanner, 'General Introduction,' A Descriptive Catalogue...", p. 170; 4 Tanner, 'General Introduction,' A Descriptive Catalogue...", p. 137; 5 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea,1st ed, 1731, p. 117; 6 Regulations and instructions...", p. 119; 7 '49. Mutiny on the ship Adventure' Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, Ed Fox, ed., p. 255; 8 William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea, 1734, p. 180; 9 Ralph Davis, The Rise of the English Shipping Industry in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, 1962, p. 111; 10 Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey 1669-1713, 1927, p. 205; 11 Bowrey, p. 222; 12 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 287; 13 Rogers, p. 287; 14 Rogers, p. 312 and Edward Cooke, Voyage to the South Seas, V. 1, 1712, p. 358; 15 '71. Deposition of Benjamin Franks'', Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period - Illustrative Documents, John Franklin Jameson, ed., 1923, p. 191; 16 George Roberts, The four years voyages of capt George Roberts, 1726, p. 51; 17 Roberts, p. 102

Steward Location

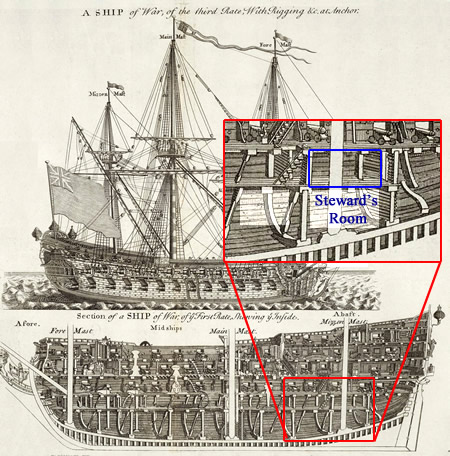

The navy spelled out the location of the steward's room on a vessel. Nathaniel Boteler puts him "in the Hold of the Ship designed for himself, which is called the Stewards room, Where also he Sleeps and Eats."1 Boteler's description is a bit vague and it sounds as if he is describing the steward's quarters rather than the room where the food was secured. Historian Brian Laverly gives a fuller explanation of a steward's room, placing it not in the hold, but in the aftmost area (that closest to the back of the ship) on the the deck just above the hold - the orlop deck. It contained "a small area for the steward's bedplace; he was probably the most junior member of the complement to be given the privilege of a fixed and private space for his bed."2

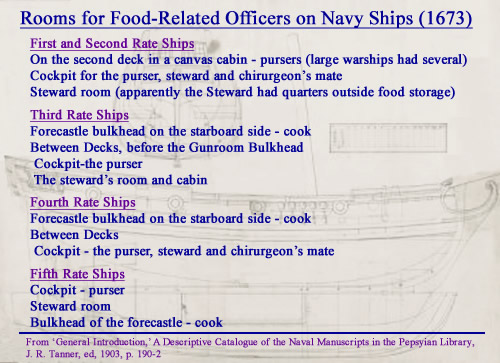

Rooms for Food-Related Officers on English Navy Ships (1673) - Image: Draught of HMS Lion

More official records place the steward's cabin in different places, depending on the ship's rating. In July of 1673, the navy published "An establishment of cabins fit to be allowed to a ship of each rate in the royal navy" at the behest of the admiralty. This was in an effort to prevent the "'very great charge and many other inconveniences rising by the unlimited number of cabins' built in the king's ships."3 Rooms of interest to this article can be seen in the graphic at right. The cockpit was located on the orlop deck at the aft of the ship, which is in line with that described by Laverly. (For a full discussion of the location of the cockpit see this page.) Note that the document quoted in the graphic says little about the officers' room locations on sixth rate warships; it does say "Cockpit built in hold —the boatswain, carpenter, gunner, and other officers"4 which likely includes the steward. (Pursers were not assigned to sixth rate ships at this time.)

The steward's room contained large bins for short-term storage of food with the steward daily issuing the items which required boiling to the cooks and food not requiring such preparation to the men in charge of each sailor's mess. Bread and goods which needed to be kept dry were put in a separate room close to the steward's room for easy issuance by him.5 Laverly doesn't go into detail about the steward's process, but on long voyages, the casked food (which included salted meats and fish and butter) was kept in the hold until it was ready for issuance. Since the steward issued food to the cooks, casked foods currently being issued were likely in the steward's room. Other foods found there included cheese, sugar (for use in punch and oatmeal), peas, oatmeal, and alcoholic beverages.

Location of the Steward's Room on a Third Rate Warship

Image From Ephraim Chambers' Cyclopedia, Vol. 2 (1728)

Storage rooms such as the steward's were also called lazarettes and they are often referred to using this term in accounts from the golden age of piracy. During a voyage aboard the 150 ton Saint George from England to Jamaica in 1686, mathematician John Taylor mentions in his journal that some convicts they were transporting "got thro' the bulkhead of the lazareta, and stole from thence 46 bottles of clarret, and one Cheshire cheese and som other things"6. He later says that some of the trouble making convicts were "stapled down to the deck in the darke lazareta, to see if this sable [dark] retierment would mitigate their stubourn and resolut spirits."7 It seems unlikely that the men would have been put in steward's room with the food given their previous behavior, suggesting this passage may refer to a different room.

On the slave ship Hannibal, Thomas Phillips describes a fight with a French privateer in late November of 1693 in his journal, noting, "We had a hogshead of brandy shot in our lazaretta, whose loss we much regretted."8 In the testimony against William Kidd, it was mentioned that Quartermaster Ham Edgell was punished because while "working in the Lazaretta, did break open a Box, and stole about a dozen pound of white Suger"9. In another entry involving a break-in to the steward's quarters Woodes Rogers mentions, "our Lazareto Door [was] broke open, [resulting in our] losing Bread and Sugar"10. Rogers' account is interesting in that the bread a sugar were kept in the same room. Without a plan of his ship, it is impossible to say if the relatively medium-sized 320 ton Duke rated a separate bread room, although, as the previous section note, the steward kept the key to this room on his person suggesting it may not have been the same room where he slept.

1 Nathaniel Boteler, Colloquia maritima or Sea Dialogues, 1688, p. 20; 2 Brian Laverly, The Arming and Fiting of English Ships of War, 1600-1815, 1987, p. 195; 3 J. R. Tanner, 'The Administration of the Navy from Restoration to Revolution: Part II - 1673-1679', The English Historical Review, October, 1897, p. 683; 4 'General Introduction,' A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, J. R. Tanner, ed, 1903, p. 192; 5 Laverly, p. 195; 6 John Taylor, Jamaica in 1687, David Buisseret ed, 2010, p. 18; 7 Taylor, p. 20; 8 Thomas Phillips, 'A Journal of a Voyage Made in the Hannibal', A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol. VI, Awnsham Churchill. ed., p. 181; 9 '49. Mutiny on the ship Adventure', Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., pp. 255-6. The editorial notes mistakenly identify the lazarette mentioned here as the sick room in this text. Sick rooms were indeed sometimes called lazarettes, although the reference to a food storage room is more common in sea accounts from this period; 10 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 287