Booze, Sailors & Health Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Next>>

Booze, Sailors, Pirates and Health In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

Alcohol

A variety of different alcohols are found in the sea accounts from the golden age of piracy. Some had wide use, while others did not.

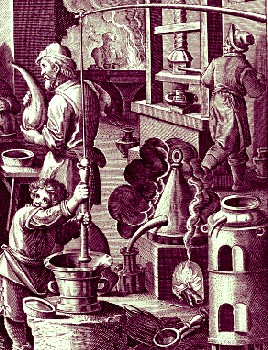

Artist: Jan van der Straet

Distilling Spirits, Wellcome Collection (16th-17th c.)

Whiskey (sometimes referred to around this period as 'usquebaugh', a corruption of the Gaelic phrase for water of life: Uisage Beatha) doesn't appear in the golden age sailors accounts.1 This is likely because it was mostly made on a small scale and was not particularly good.2 As a result, export of whiskey from Scotland did not begin in any serious manner until well after the golden age of piracy. Another drink the Dutch made around this time was gin or geneva. It fails to be mentioned in the sailor's documents1, although gin enjoyed wide popularity in England shortly after the end of the golden age of piracy. Widely available during this period was aqua vitae, although this does not appear in English sailor accounts either.1 It's probably just as well; mixologist David Wondrich reports, "At its all-too-common worst , aqua vitae would have been a stinking, oily potion that burned like Sherman's march going down and left you the next morning with a head as pulpy and tender as a rotten jack-o'-lantern."3 John Ovington does mention aqua vitae while he is on land in Surat, India, noting "Of

this sort of Liquor there are two kinds

most fam'd in India, the Goa and Bengal Arak, besides that which is made at Batavia."4 Since these are just types of arrack (fermented palm wine), Ovington used 'aqua vitae' as a generic term for an alcoholic beverage rather than the specific distilled liquor popular in Europe.

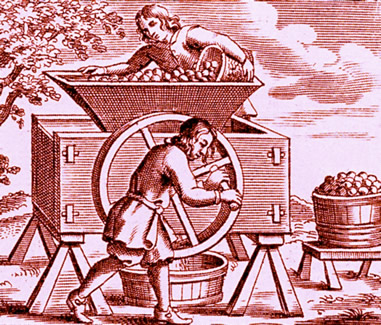

Another alcohol which is mentioned more often, although still only in a handful of accounts is cider. Cider, usually made from apples and sometimes from pears,

Making Red Streak Cider, From A Treatise on Cider, By John Worlidge (1678)

was something of an English specialty. However, cider was not produced on a large scale the way beer was, usually being made on farms during this period. "In the 17th century cider wasn’t the cheap drink that it is today as apples were difficult to press. You needed a powerful mechanical press to extract the juice which only the rich could have afforded to own in 17th century England."5 A weaker type of cider was made from apples which "had already been pressed mixed with water known as Ciderkin. Most modern ciders are closer to Ciderkin than good 17th century cider."6

Cider appears six times in the sailors accounts - twice as being used by naval officers and four times as being used by pirates.

Chaplain Henry Teonge mentions cider in his account of his time aboard HMS Bristol. He doesn't really have much to say about it, other than it was one of the 'answerable' (meaning 'suitable') alcohols the captain provided to the officers.7 He also mentions that the cider they had on board came from a provisioning stop in Plymouth, England.8 Since it is not mentioned anywhere else in his book, It was likely gone before they reached the Mediterranean.

The pirate reports are a little more informative. Reporting on logwood cutters, Captain Nathaniel Uring reported that when they could get it, they would drink "Bottle Ale or Cyder

Making Cider, From A Treatise on Cider, By John Worlidge (1678)

"9. Cider is also mentioned in Johnson's account of Bartholomew Roberts, where he explains that in Sierra Leone, Africa "many of our trading Ships, especially those of Bristol ...call in there, with large Cargoes of Beer, Syder, and strong Liquors, which they Exchange with these private Traders, for Slaves and Teeth"10.

When Captain Kidd was making his way back to Boston after committing various piracies in the East Indies, he stopped at Gardiner's Island off Long Island to resupply his ship. While there, "Kidd asked him [the island's proprietor, John Gardiner] to spare a barrel of Cyder, which the Narrator with great importunity consented to, and sent two of his men for it, who brought the Cyder on board said Sloop"11. In return for this and other supplies, Kidd gave him some damaged cloth and other small items as recompense. The cider was likely made by Gardiner himself. Ale and cider are also mentioned as plunder taken by Thomas Anstis off a sloop near La Désirade in the French West Indies.12 Other than its being taken, nothing else can be gleaned from this account, although, the ale and cider may very well have been locally made. In the end, based on these accounts, this was clearly not a regular drink for the common sailor.

There are still plenty of beverages that are mentioned frequently enough to warrant greater exploration. These include beer (and ale), wine, arrack or palm wine, beverage wine, brandy, rum and punch. Beverage wine and punch are in fact types of mixed drinks, but they are mentioned separately from their ingredients in many of the sailor's accounts, so they have been featured in their own sections.

1 This is based on a search through Philip Ashton, Ashton's Memorial, 1726, Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, William A. Betaugh, A Voyage Round the World, 1728, William Bosman, A New and Accurate Description of the Coast of Guinea, 1705, Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World in the Years 1708 to 1711, 1712, Edward Coxere, Adventures by Sea of Edward Coxere, 1846, William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, Ed Fox, Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, Thomas Gage, A New Survey of the West Indies, 1677, Alexander Hamilton, British sea-captain Alexander Hamilton's A new account of the East Indies, 17th-18th century, 2002, Bruce S. Ingram, Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, John Ovington, A Voyage to Suratt in the Year 1689, 1696, George Roberts, The four years voyages of Capt. George Roberts, 1726, Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, Captain William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea and the Slave Trade, 1734, Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, Chaplain on Board H.M.'s Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, 1675-1679, 1825 and Nathaniel Uring, A history of the voyages and travels of Capt. Nathaniel Uring, 1928; 2 See Henry Jeffreys, Empire of Booze, 2016, pp. 213-5; 3 David Wondrich, Punch, 2010, p. 9; 4 Ovington, p. 237; 5 Henry Jeffreys, Empire of Booze, 2016, p. 18; 6 Jeffreys, p. 20; 7 Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, Chaplain on Board H.M.'s Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, 1675-1679, 1825, p. 28; 8 Teonge, p. 25; 9 Nathaniel Uring, A history of the voyages and travels of Capt. Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 241; 10 Captain Charles Johnson, A general history of the pirates, 3rd Edition, 1724, p. 253; 11 “79. Narrative of John Gardiner. July [17], 1699”, Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period Illustrative Documents, John Franklin Jameson, 1923, p. 193-4; 12 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 462

Alcohol: Beer and Ale

Beer was the baseline of alcoholic beverages. In 1674, the navy was in the practise

Photo: Peter Isotalo

Casks of Beer, From the Vasa Ship Model

of giving each man aboard a gallon of beer a day, every day, based on a description of the system by Captain Stephen Pyend.1 A contract from December of 1677 mentions that every man was "to have for his allowance by the day... one gallon, wine measure, of beer"2. Keep in mind that a wine measure was about 18% less than an beer measure (with a standard wine gallon containing 231 cubic inches and a standard beer gallon containing 282). The Royal Navy's regulations of 1731 reiterated this amount of beer in chart form3, so this practise continued all throughout the golden age or piracy

There were differences in the beer served to the navy. Historian J.D. Davis explains, "There were three different kinds of beer. Iron-bound ‘sea-beer’; for ships on extended voyages, had twenty quarters of malt to every twenty tons of beer; wood-bound ‘Channel-beer’ had eighteen, while wood-bound ‘harbour-beer’ had twelve."4 Such differences are primarily concerned with the size of the cask and the types of hoops it was bound with. Wood hoops were used close to home because they were cheaper than iron. However, being less durable, they were not supposed to be used for longer voyages.

There was another difference in the beer during this period, however. Two types of beer were used at sea: small beer and strong beer. Since there was no good way to measure alcohol content during this period, the strength of the

A Composite Chart Taken from Frederick Accum's A

Treatise On

Adulterations of Food, pp. 211-2 (1820)

two beer types would have been measured by taste. A more precise measure of the alcohol found in small and strong beers was not accurately defined until the introduction of Sike's hydrometer in 1816.

In 1820, Frederick Accum published a book on the adulteration of food in which he cited some experiments performed on the alcohol content of various beers. The results can be seen in the chart at left. Porter and stout became popular after the golden age of piracy, although stout is mentioned in one of the pirate accounts. So we will use it as an example of strong beer, since ales didn't contain hops.

From Accum's nineteenth century data, stout runs from 5.00 to 6.80 parts of alcohol per measure (by volume) based on Sikes hydrometer. Small beer, on the other hand, runs from 0.75 to 1.28 parts per measure of alcohol.5 (How this compares to modern proof numbers is certainly open to debate, although the numbers seem fairly consistent with what might be expected.) So the small beers were small indeed, if these numbers reflect those of the alcohol content from a hundred years previous! Note that the small beer's alcohol content is only about twice that found in what are called non-alcoholic beers in the United States today. (By US Law, non-alcoholic beers must contain less than 0.5% alcohol by volume.)

Ephraim Chambers explains how beer as made in his Cyclopaedia:

Artist: Jost Amman - Beer Brewer (1586)

Brewing, the Preparation of Ale, or Beer from Malt. The Process is as follows. A Quantity of Water being boil'd is left to cool, till the height of the Steam be over; when, so much is pour'd to a Quantity of Malt in the Mashing Tub, as makes it of the Consistence stiff enough to be just well row'd up: After standing thus 1/4 of an Hour, a second Quantity of Water is added, and row'd up as before. Lastly the full Quantity of Water is added; and that in proportion as the Liquor [liquid] is intended to be strong or weak: This part of the Operation is called Mashing. The whole stands two or three Hours, more or less, according to the strength of the wort [liquid from the mashing process], or the Difference of Weather, and is then drawn off into a Receiver; and the Mashing repeated for a second Wort, in the same manner as the first... The two Worts then mix'd, the intended Quantity of Hops are added, and the Liquor close cover'd up, gently boil'd in a Copper the space of an Hour or two; then let into the Receiver, and the Hops strain'd from it into the Coolers.6

The liquid was then left to ferment. Chambers goes on to say, "For Double Beer or Ale, the two liquors resulting from the two first Mashings, must be us’d as liquor for a third Mashing of fresh Malt for Fine Ale. The Liquor [liquid] thus brew’d, is further prepar’d with Molosses."7 He then briefly gives the recipe for making small beer: "For Small Beer there is a third Mashing, with the Water near cold, and not left to stand above ¼ of an Hour, to be hopp’d and boil’d at Discretion." 8

Small beer did not often meet with approval.

Engraver: Robert White - Thomas Tryon (1703)

Ascetic Thomas Tryon said it was "a very ill sort of Drink; for the first and second Liquors have extracted or drawn forth all the brisk, lively sweet Qualities of the Mault, so that this third hot Liquor hath nothing to work on, or draw forth, but only a gross Substance, stinking, harsh, bitter, or keen Quality, void of all the Seminal or sweet Virtues."9 He further condemns it by explaining that "most small Beer, especially that which is made after Ale or strong Beer, is injurious to Health, and the common drinking thereof does generate various Diseases, but more especially the Scurvy in the Blood; therefore all that do regard their Health, ought to forbear drinking such ill prepared Liquors."10

The pirates apparently agreed with Tryon on this point. During the mock trial Johnson put into the chapter on pirate Thomas Anstis, the prosecuting solicitor says, "we shall prove, that he has been guilty of drinking Small-Beer, and your Lordship knows, there never was a sober Fellow but what was a Rogue."11

Small beer appears to have been what was served throughout the day to non-pirates. In making the case against mutineer Joseph Bradish who took the merchant ship Adventure in March of 1698, information was presented that explained daily life on the ship before the mutiny. Surgeon Samuel Nixon wrote a letter which explained that the men "had three Can[n]s of Beer a Mess every day till far beyond the Cape of good Hope, and after that two Can[n]s of good Beer and Water"12. This does not give us any information about the beer, but Nixon later explains "that every Mess had on Sundays a Can[n] of strong Beer"13. So the three and then two canns of beer given the rest of the time must have been small beer. This practise likely came courtesy of the Navy.

While the navy contract of 1677 quoted at the beginning of this section does not specifically state what kind of beer that the men were issued, it does say "in lieu of a gallon of beer, a wine quart of beverage wine or half a wine pint of brandy"14 could be served. Beverage wine was watered down wine. Considering Samuel Nixon's explanation of life aboard the merchant vessel Adventure where

A Later View Portsmouth Harbor as Seen From Gosport

small beer was normally served and the fact that a gallon of the navy beer was felt to be equivalent to a quart of watered down wine, the Navy was almost certainly serving its men small beer. This explains why they could drink a gallon of it a day. Modern historian Angus Konstam says, "For the most part this 'small beer' [given to navy sailors] was brewed in the Navy's own brewery in Portsmouth."15

Modern authors like to explain how sailors drank beer because the water was so bad. However, as the article on Fresh Water at Sea explains, ships took in large amounts of fresh water, allowing an estimated half gallon per day per man for drink. Besides, the beer probably wasn't much healthier than the water, as we shall see shortly. Another favorite idea promoted by modern authors is that the beer was necessary to provide calories to sailors. There is some truth to this in that small beer had some calories, although was likely about 1/4 to 1/2 as many calories as strong beer based on a comparison of modern small and non-alcoholic beers and modern regular beers. This may have been why Thomas Tryon inveighed against small beers. In his book on brewing beer, he explains that

as the Substance of our Bodies offers a daily Expence, Decay, or Wasting, as well by the Action of our own innate (or inbread heat,) perspiration of Spirits, and the more pure parts of the Humours through the pores of the Skin, Impressions of the Ambient Air, as by the common and more gross Evacuations; so there is required a daily supply of Nourishment to repair and make good whatsoever is thus spent of the Store which is provided to support and preserve the Microcosm.16

The modern authors should love him.

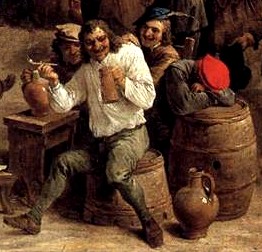

Artist: David Teniers the Younger (1650)

Of course, once the sailors reached port, all bets were off. Edward Barlow commented in a 1674 journal entry from his time on the ship Berff van Liden, "They have indifferent good beer here in this place [Bergen, Norway], which is brewed with molasses and some malt and is very brown, but tastes much of the smoke. They sell it for a penny a quart, which is not dear in that place, for several of our men would be fuddled oft enough with it, yet we had better beer on board"17. (Write that down and paste it in your hat - it's not often you find Barlow complimenting the victuals shipboard, particularly early in his career.) When he was in Greenock, Scotland the next year aboard the fflorentine, he said, They have indifferent good beer here, only it smells strong of smoke as it doth in Norway."18

Artist: George Cruikshank

From Voyage to Margate (1786)

The pirates also appreciated strong beers. As mentioned in the section on bottles, when mutineers Phineas Bunce and Dennis Mccarty were preparing to take over the sloop Mary, they started by getting into position among the men they needed to capture by requesting bottles of beer from the supercargo's supply. This would almost certainly have been strong beer. "Mr. Carr readily went down, and brought up a Couple of Bottles of Beer: They sat upon the Poop with Captain Augur in their Company, and were drinking their Beer; before the second Bottle was out, Bunce and Macarty began to rattle, and talk with great Pleasure, and much boasting of their former Exploits when they had been Pyrates"19. Two bottles of small beer would hardly have had this effect. (Provided anyone had even bothered to bottle such stuff in the first place rather than shove it into a cask.)

Nor would the officers on a naval ship be likely to drink small beer. When Sir Andrew Leake was being treated by naval physician William Oliver, Oliver tried to get him to drink cordial waters - a weak alcoholic mix with herbs added to impart healing properties to the water. Oliver reported that Leake didn't much care for the cordials, saying "that he abhorr’d the very smell of them and assur’d me he would Die rather than take them". Not wanting to displease the captain, Oliver

Artist: Adriaen van Ostade (c. 1635)

instead administered his medicines in "a Julep made of Ship-Beer, and some of his own Margate Ale, which he lov’d mightily, and drank with a great deal of Pleasure to the end of his Fever, and did well."20

Chaplain Henry Teonge discusses beer both as a drink for the before-the-mast sailors, and among the officers with which he regularly dined. The difference between these citations is striking. When talking about the beverage for the regular sailors, Teonge simply notes that 'beere' is brought aboard Harwich in May of 167821 and in the Downs [off the Kent coast] in September of the same year22. However, when describing the officers drinking it at a celebration of the King's birthday in 1678, he says the meal was "washt downe with good Marget ale, [and] March beere", among other drinks.23 Ale was difficult to get, even for the officers. When discussing a feast given aboard the Assistance, Teonge mentions that they had "good sack, mountaine Aligant[e wine], clarett, white wine and English ale, the greatest raryty of all."24

Beer is mentioned twenty-two times in the sailor's accounts, including three naval accounts25, five navy officer accounts26, eight merchant and privateer accounts27 and seven pirate accounts28. Ale only appears in five accounts, which includes four naval officer accounts29 and one pirate account.30

1 J.R. Tanner, ed., A Descriptive Catalog of Naval Manuscripts in the Pepysian Library, 1903, p. 160; 2 Tanner, p. 166; 3 Regulations and Instructions relating to His Majesty’s Service at Sea, 1731, p. 60; 4 J.D. Davies, Pepys’s Navy, 2008, p. 202; 5 Frederick Accum, A Treatise On Adulterations of Food, 1820, p. 212; 6,7,8 Ephraim Chambers, "Glasses", Cyclopedia, Vol. 1, 1728, p. 126; 9 Thomas Tryon, A New Art of Brewing Beer, Ale and other Sorts of Liquors, 1691, p. 20; 10 Tryon, p. 22; 11 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 293; 12 Ed Fox, “49. Mutiny on the Ship Adventure”, Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 254; 13 Fox, “49. Mutiny on the Ship Adventure”, Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 255; 14 Tanner, p. 167; 15 Angus Konstam, Navy Miscellany, 2010, p. 139; 16 Tryon, p. 2-3; 17 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 236; 18 Barlow, p. 266; 19 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 628; 20 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, 1958, p. 25; 21 Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, Chaplain on Board H.M.'s Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, 1675-1679, 1825, p. 238; 22 Teonge, p. 257; 23 Teonge, p. 238; 24 Teonge, p. 44; 25 Barlow, p. 53 & Teonge, p. 238 & 257; 26 Teonge, p. 25, 28, 238 & 304; 27 Fox, “49. Mutiny on the Ship Adventure”, Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 251 & 254, Barlow, p. 236, 266, & 540, Francis Rogers from Bruce S. Ingram's book Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 182 & 197 & Captain William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea and the Slave Trade, 1734, p. 28; 28 Fox, “2. William Phillips The Voluntary Confession and Discovery of William Phillips, 8 August, 1696. SP 63/358, ff. 127-132”, Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 29, Fox, “67. Prices of Pirate Supplies: A List of the Prices that Capt. Jacobs sold Licquors and other Goods att, at St. Mary’s, 9 June, 1698…”, Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 362 & Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 293, 469, 507 & 628, Weekly Journal or Saturdays Post, 8-24-23, Issue 252; 29 Teonge, p. 28, 44, 238 & John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, 1958, p. 231; Fox, “43. 30 Henry Treehill, from The Information of Henry Treehill, 21 March, 1724. HCA 1/55, ff. 64-68”, Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 203

Alcohol: Beer Gone Bad

"[July, 1653] The Navy Commissioner [Nathaniel] Bourne ...stated that even the new beer for the fleet was ‘so bad as none can be worse’, and must be thrown overboard." ( John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, 1958, p. 4)

There were a variety of complaints about the badness of the naval beer. Historian J.D. Davies notes, "Men seem to have been prepared to put up with bad food as long as they had decent beer."1

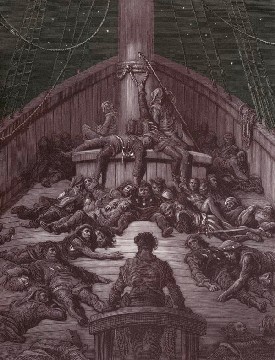

Artist: Gustav Doré

A Sickly Ship, From

Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1876)

Most of these complaints pre-date the golden age of piracy, with many occurring during the three seventeenth century Anglo-Dutch wars which took places between 1652 and 1674. The strain on the victualling system would have been great as they tried to equip the large number of naval vessels being prepared for war.

Writing in 1653 during the first Dutch War, General-at-sea George Monck "attributed much of the sickness to beer which was unfit to drink, and unlikely though this may now appear as a source of infection"2. Two years later, Navy Commissioner Thomas Middleton wrote to Samuel Pepys that the H.M. Coventry's "beer had nearly poisoned one man, who, 'being thirsty, drank a great draught.'"3

Edward Barlow, serving aboard the H.M. Monke in 1667, gave this unflattering description of the Navy's beer: "drinking a little small beer, which is as bad as water bewitched, or, as the old saying is amongst us seamen- ‘Take a peck of malt and heave it overboard at London Bridge, and let it wash or swim down the river of Thames as low as Gravesend, and then take it up.’ It would make better beer than we drunk"4. In 1673, the victuallers used wood bound casks to carry the beer, possibly marking it for Harbor or Channel use. "These barrels could not withstand the effects of being moved about when ships rolled and pitched, so that those containing beer and water were staved in, and those containing fish leaked the brine in which they were preserved and had to be dumped. Consequently the fleet had to return prematurely from the Dutch coast"5.

Whatever the reason they failed to provide iron bound casks, bad beer routing the fleet would have been a pretty black mark against the victuallers and they got their share of grief. When the fleet returned, Prince Rupert "wanted to have the victuallers responsible brought in custody to the fleet and compelled to remain to share the dangers and diet of the seamen."6 In September 1672, complaints of bad

Artist: Hans Holbein the Younger

Someone Not Enjoying the Ship's Beer, From

Ship

With Revelling Sailors (1532-3)

beer were officially presented to them, "but the victuallers replied ambiguously that their beer was as good as ever was used in the fleet, and they counted themselves happy in that they had been afflicted with less bad beer ‘by many degrees than ever was in such an action."7 Even so, in the same month of that year "the captain of the Newcastle reported that he had thrown overboard 42 butts of beer, it being stinking and not fit for men to drink'"8. A month later, the captain of the Augustine wrote that of "20 butts or more he could not find four sweet [as opposed to sour], and the doctor attributed the sickness among his men to the extreme badness of the beer"9.

The Navy was concerned about the matter. In August of 1678, four years after the end of the Third Dutch War, Samuel Pepys wrote to the navy board. " I am extremely sorry to meet with such daily complaints as I do touching the badness of the provisions sent on board his Majesty's ships,' and refers to a letter just received from one of the captains, ‘complaining of the badness not only of his beer but his other provisions, and setting forth the very ill effects thereof upon the healths of his men.'"10 However, the situation does not appear to have improved, with Pepys writing additional letters of complaint about the victuallers in December of that year. They met with the victuallers in March of the next year, although nothing seems to have been resolved. "The Victualling Commissioners blamed it all on lack of money."11

Later examples show continued problems with the Navy beer after the end of the last Dutch War. "Several of the Eagle Fireship’s men deserted her in 1675 in protest at the poor beer they were being expected to drink; at much the same time, the captain of another fireship grumbled that his beer was ‘worse than any water, they do but spoil good water in brewing such’."12 During

Artist: Thomas Gibson - Admiral Edward Russell (1715)

the War of the League of Augsberg (1689-97), "the beer was singled out for particular condemnation; 'the Men chose rather to drink Salt Water or their own Urine'."13 In July of 1689, Admiral Edward Russell reported that in the Blue Squadron

many ships were 'extremely sickly' ... and no longer agoe then yesterday, in several of the buts of beare, great heapes of stuff was found at the bottom of the buts not unlike mens' guts, which has alaramed the seamen to a strange degre'. It was said that dogs which had eaten the seamen's victuals died and that the beer remained undrinkable even after boiling.14

One of the above comments notes that the men did not like beer because it was no longer swert, indicating that it had become too sour to drink. One of the reasons that beverage wine [watered down wine] or brandy was served in lieu of beer in the Mediterranean and rum was allowed in the West Indies in place of beer was that the heat of those environments caused the casked beer to become sour and go bad faster. "Without the antimicrobial properties of the hops, and before the use of sterile culturing techniques, all beer would have begun to sour within days or weeks of brewing."15 Beer which spent more than a few weeks in the cask at sea would necessarily have become sour over time because of the wild yeast used in the making of the beer and the bacteria that were either in the beer or in the casks the beer was put into. Heat accelerated the action of such bacteria, which would have caused the beer to go bad at a faster rate.

1 J.D. Davies, Pepys’s Navy, 2008, p. 202; 2 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, 1958, p. 4; 3 J.R. Tanner, “Introduction”, Naval Manuscripts in the Pepysian Library, Vol. 1, 1903, p. 153; 4 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 127; 5 J.R. Jones, The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the Seventeenth Century, 1996, p. 59-60; 6 Jones, p. 60; 7,8 Tanner, p. 158; 9 Tanner, p. 158-9; 10 Tanner, p. 179; 11 Keevil, p. 173; 12 Davies, p. 202; 13,14 Keevil, p. 173; 15 Michael Tonsmeire, American Sour Beer, 2010, p. 1

Alcohol: Beer and Heath

Beer was discussed by sea surgeons in a variety of illnesses. It appears in recipes for some of the medicines the sea surgeons carried including Cervissa Purgans (Purging beer) where strong beer being a primary ingredient),

From Administration de Efficaci Medicina, libri

tres, By Marco Aurelio Severino (1646)

as a medium for dissolving Crocus Martis which is given for fluxes or diarrheas, as an ingredient in Oleum Vitrioli (Oil of Vitriol), in Potus Apertive (Opening Liquid) which is made with 'new beer', in Extractu Cassiae pro Cysterbus, and a medium for Spirtius Nitri Dulcis (Sweet Spirit of Nitre). Spruce beer is used in Traumatic Haustus, although that is made differently than regular beer.

Beer also features in some of the recommendations given for individual cures. Sea surgeon John Woodall advised its use in a variety of illnesses. He recommends it for lienteries where the stomach "must be strengthned, both inwardly and outwardly, by things that corroborate [strengthen] and warme the same ...[including] Chimice [absinthe oil] three or foure rops thereof in wine, or beere for neede"1. Woodall also advised that for patients with fractures, a German patent medicine called Lapis Zabulousus or or Lepis Abulosus be "inwardly taken daily the quantity of {1 ounce} in fine powder in wine, beere, or water, the patient fasting for two houres after the taking thereof. In great fractures, the Germane Surgions, prescribe this aforesaid medicine daily to be taken for twenty foure dayes, if they see cause so long to use it"2. Woodall quoted classical physician Paracelsus' use of "Common sea salt, boyled in the strongest beere to the consumption of three parts of the same beere and being made salt as Brine" for use in gout, similar aches, rheumes (watery discharge in the eyes and nose) and skin diseases.3

Woodall suggests an external use for beer, bathing patients infected with scabies using hot salt water combined with strong beer. The patient was to "sit in [the bath] and sweat therein, and after go to a warm bed and sweat againe, and doing so sundry times, they shall feele helpe thereby."4 (Sweating was believed to be a way to purge the body of foul humors.) Somewhere between external and internal use, warm beer was one of several things suggested to be used as an enema in drowning cases to help revive a nearly drowned patient.5

Sea Surgeon John Moyle

Sometimes beer could be used, but only the right sort of beer. For head injuries, fellow sea surgeon John Moyle advises a strict diet, warning that the patient should "not [be given] to drink Wine nor Brandy, nor any strong Liquor; but let only Barley water, or small [low alcohol content] Beer"6.

Beer was also sometimes said to have deliterious health effects. German surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purmann blames 'spontaneous looseness' on eating bad foods and "drinking after them New, Muddy, Thick, Nasty Beer or Ale."7 Woodall concurs, explaining that "sometimes it [diarrhea] happeneth here in our Countrie, as some English Writers affirme, by little drinking of beere or ale, and sometimes it commeth by drinking too much wine"8. Moyle felt the sailors who drank only beer and water more more susceptible to scurvy because they "have not the saniferous juice of the Grape to conserve the right Temper of the blood."9 Woodall, on the other hand, says that scurvy is in part caused by "want of Aqua vitæ, wine, beere, or other good water to comfort and warme their stomackes"10. When sweating a patient to remove the bad humors, Thomas Sydenham orders that "cold beer be carefully avoided", instead recommending the patient only use "Drinks [which] are somewhat hot."11

Physician Tobias Venner had quite a bit to say about beer. He said that if it hadn't been over-hopped and wasn't too bitter, he trumpeted the

wholsomenesse and excellency of Beere; for hops does not onely remove obstructions of the liver, spleene, and kidneys, and cleanseth the bloud from all corrupt humours, causing the same to come forth with the urine, which it provoketh; but also, maketh the body soluble [loose and open], by excreting forth of yellow cholerick humours [yellow bile - one of the four primary humors in the body]. Wherefore seeing that hope doe as well make Beere a kinde of medicinable drinke, to preserve the powers and faculties of the body, and to purge and cleanse the bloud [another of the four primary humors], as a common and daily drink to extinguish thirst , I may very well conclude, that it is much better and wholesomer than Ale, especially for such as be cholerick, and have hot stomacks, and that are subject to obstructions of the milt [spleen], liver and kidneys.12

Artist: Wolf Helmhardt von Hohberg - Hops Farm (1695)

He does not have much use for hoppy beer, however. "Beere that is too bitter of the hop (as many to save Mault are wont to make it) is of a fuming nature, and therefore endangerth rheumes and distillations, hurteth the sinews, offendeth the sight, and causeth the head-ach"13. Venner also recommends beer "of a middle-age, as from one or two moneths old, unto five or six, according to the strength of it, is the best and wholsomest."14 He goes on to explain that such beer "represseth the acrimony of choler [black bile, a third of the four primary humors], and also to all them (by reason of the penetrating force which it obtaineth) that are subject to the obstructions of the stomack, mesaraick veines, spleene, liver, lungs and reines [kidneys], it is most profitable."15 He also explains that the most healthful beers are "of an indifferent strength, not too strong, nor too small, because each excesse is hurtfull."16 He finishes by noting that getting drunk on beer is bad because "the fumes and vapors of the Ale or Beere, that ascend to the head, are more grosse, & therefore cannot be so soone resolved [dissipated by the body]."17

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 202-3; 2 Woodall, p. 163; 3 Woodall, p. 275; 4 Woodall, p. 275-6; 5 John Wilkinson, Tutamen Nauticum or The Seaman's Prevention from Shipwreck, Diseases and Other Calamities Incident to Mariners, p. 7; 6 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 115; 7 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, p. 331; 8 Woodall, p. 242; 9 Moyle, p. 181; 10 Woodall, p. 179; 11 Thomas Sydenham, The Whole Works of Dr. Thomas Sydenham, 3rd ed, 1701, p. 75; 12 Tobias Venner, Via Recta ad Vitam Longam, 1638, p. 44-5; 13 Venner, p. 44; 14,15,16 Venner, p. 48; 17 Venner, p. 49

Alcohol: Flip

One beverage mentioned as being tied to sailors was a mixed drink called flip. Several websites suggest this first appeared in 1695. It is mentioned not once, but twice in books from that year. It appears most tellingly in the play Love for Love by William Congreve, with one of his characters proclaiming, "We're merry Folk, we Sailors, we han't much to care fore. Thus we live at Sea; eat Bisket, and drink Flip; put on a clean Shirt

Artist: Amedee Forestier

Pirate Drinking From Cann, From 'The world went very well

then,' By Walter Besant (1888)

once a Quarter"1. This is a rather broad characterization of course, but it suggests that the concoction was widely drunk by sailors. Even more interestingly, it appears in official communications preserved in the Navy records in February of that year. An unsigned memorandum sent to the Navy Board talked about problems that might occur if they reduced the sailor's daily allowance of small beer notes, " In the summer, through the heat of the weather, the men drink very near (if not their full) allowance of beer, and at all other times a great quantity is expended in making cans of flip etc."2 Taken together, it would appear that, in the navy at least, this was a well-known cocktail in 1695, almost certainly predating that.

So what was flip? Jno Connolly pointed out one of the earlier actual receipts for ale flip found in an 1817 cookbook: "Beat two eggs for about ten minutes, mix half a tablespoonful of moist sugar, and as much grated nutmeg as will lie on a shilling. Put a pint of ale into a saucepan; when it is hot, pour it into a basin to the eggs, &c., and back again into the saucepan, and back again three or four times, till it is quite smooth."3 However, this is far too complex a recipe for most naval sailors to have concocted shipboard, and several of elements were not likely found when at sea by a typical sailor including eggs, ale and nutmeg. The ship's officers might have had these things because they purchased and brought their own food aboard including live hens for laying eggs. But they would not have been available to the average sailor unless the ship was in port and he had money enough to purchase them. In addition, few would have had access to saucepans and stoves. Fires shipboard were usually limited to the cook room and then typically only during times when cooking was taking place, whcih occurred when the ship wasn't moving.

Some Flip Recipes from Jerry Thomas' Bar-Tender's Guide (1876)

Of course, recipes for flip vary quite widely. (As late as 1876, Jerry Thomas saw fit to include eight different types of flip in his Bar-Tender's Guide, including two 'cold' ones in the Appendix.) However, any drink 'recipes' would have been quite fluid during the golden age of piracy, being made with whatever elements were at hand. To understand what the average navy man would have been drinking, it is necessary to get at the essential nature of the term flip. Several Dictionaries from the period give the same recipe for the word: ale, brandy, and sugar.4 They all run along the same lines, likely having been copied from one dictionary to another and slightly modified. A typical definition: "Flip: a sort of Sailors Drink, made of Ale, Brandy and Sugar."5

The last mention of ingredients is most telling and it comes from the trial account of John Rackham. Sailor John Hill deposed that while aboard the merchant sloop Pearl, the ship's captain "spared (them that wanted,) Brandy, and about Eight a clock at Night, he (the Deponent) begged a little Sugar, from the Doctor, and made a Can[n] of Phlip"6. It is notable that brandy was given to the sailors as a treat (being 'spared' them) and Hill had to beg the ship's surgeon for sugar to be able to complete the cocktail.

Photo: Wiki User Ilikefood

A Brandy Flip with Nutmeg on Top in a Cocktail Glass

Looking at these various recipes, the key elements of flip from the period can be discerned. One was alcohol - typically brandy and beer - and the other was was sugar. As the anonymous writer to the Navy Board suggests, navy sailors would often have used small (low alcohol) beer in place of the stronger ales and they might have had sugar available to them. (It was served with oatmeal, part of their regular provisions.) Brandy was sometimes served on navy ships in the Mediterranean, although this was usually only after they had run out of beer. In addition, it seems to have been more usual for them to be served watered-down wine based on the accounts gathered. However, merchant sailors typically brought brandy aboard with them when they joined a ship according to one historian7 and the same would likely true of navy sailors if they had the money to purchase it.

The importance of heat may be suggested by the name. Wikipedia suggests that heating the mixture "caused the drink to froth, and this frothing (or "flipping") engendered the name."8 (Unfortunately, they don't give a source for this.) Another modern article points out that heating the sugar/alcohol combination would caramelize the froth9. However, historian Ed Fox pointed out that the early recipes don't mention this element, so it is possible it may not have been a part of the sailor's early recipe.10

As ubiquitous as the two references leading this section hint that flip was among sailors, only two direct mentions

Artist: Gustav Dore

Men Asleep on Deck, From Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1876)

of it are found in the sailor's books under study. One comes from navy cook Barnaby Slush, who says that he spent some time yarning with "our Boat-swain over a Can[n] of Flip"11. He elsewhere states in an offhand manner that he would have "very happily melted away all all my smoaky Days [in what served as the galley], in the downy Embraces of a Calm and thoughful Tranquility; with now and then a small chirping Can[n] of Flip and Pipe of Tobacco."12 (Chirping here might refer to sizzling, as it would if heated. As cook, Slush would have had regular access to a stove.) The second direct reference comes from John Hill's testimony which was cited above.

An indirect reference can be found in naval physician William Cockburn's book on sailor's illnesses. He complains twice about sailors drinking either flip and punch, making them so intoxicated that they sleep in the open air on the deck of the ship and become ill.13 So these accounts place flip aboard both merchant and navy ships and although it is only found twice in the accounts studied, it likely enjoyed some popularity among period sailors.

1 William Congreve, Love for Love, 1697, p. 50-1; 5 "No. 119 Copy of a memorandum (unsigned),1 addressed to the Navy Board - February 27, 1694/95", The Sergison Papers, (Naval Clerk of Acts), R.D. Merriman, ed., 1950, p. 250; 3 William Kitchiner, Recipe 466, Apicius Redivivus, or The Cook's Oracle, 1817, not paginated; 4 For examples, see the entries for , "Flip" in Edward Phillips, The New World of Words, 1706, not paginated; John Kersey, A New English Dictionary, 1713, not paginated; and Nathan Bailey, Universal etymological English dictionary, 1724, not paginated; 5 Bailey, not paginated; 6 The Tryals of Captain John Rackam, and Other Pirates, 1721, p. 42; 7 Peter Earle, Sailors, English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775, 1998, p. 98; 8 "Flip (cocktail)", wikipedia.com, gathered 11/10/20; 9 "Hot Ale Flip," PunchDrink.com, gathered 11/10/20; 10 Ed Fox, Authentic Pirate Living History Facebook Group, gathered 22/29/30; 11 Barnaby Slush, The Navy Royal, Or a Sea Cook Turn'd Projector, 1709, p. 96; 12 Slush, "Introduction", not paginated; 13 William Cockburn, Distempers of Seafaring Peoples, 1696, p. 26 & 71