Booze, Sailors & Health Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Next>>

Booze, Sailors, Pirates and Health In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 18

Alcohol and Health

Although the health benefits and consequences of each individual liquor have already been discussed, the act of drinking any alcohol was itself seen as being both advantageous and harmful, depending on how it was drank and who was writing.

Alcohol and Health - Beneficial

“Finding that Punch did preserve my own Health [from the illness gotten at Guayaquil], I prescribed it freely among such of the Ships Company as were well, to preserve theirs.” (Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 209)

Artist: Gustavus Hamilton

Punch Drinkers, From 2nd Viscount Boyne and Friends

in a Ship's Cabin (1731-2)

Several authors felt that moderate drinking encouraged good health. Physician Tobias Venner said "it may be lawfull and expedient, for them that are wont to be wearied with great cares and labours, to drink sometimes until they bee merry and pleasant; but not drunken: for in observing such a rule; the aforesaid crapulentall Hurts [illnesses caused by over-indulgence in food or liquor] are not induced, but the spirits and the whole body are thereby so recreated, refreshed, and renewed"1.

In a letter to Lord Cliff, James Howell explained "That good Wine makes good Blood, good Blood causeth good Humours, good Humours cause good Thoughts, good Thoughts bring forth good Works, good Works carry a Man to Heaven; ergo good Wine carrieth a Man to Heaven."2 Blood was one of the four humors which medical men felt made up the body of man and wine, which looked somewhat like blood, was sometimes imbued with the ability to generate good blood.

Naval physician William Cockburn defended the sailor's 'innocent Saturday Evening Cabals', explaining "without the temperate use of spiritous liquors, their victualling, with all their fatigue, will be little enough to afford necessary Chyle gross [thick] enough to make their thick blood, that cannot be so easily sent round their bodies, without the help of a Bowl of Punch or a Can of Flip"3.

To understand this, the four stages of digestion as understood by the Greeks must be briefly explained. Chyle, a milky fluid, was believed to be produced in the 'first digestion' of food. The four fluid humors (blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile) were produced by the 'second digestion'. The 'third digestion' produced urine and sweat (thought to carry unwanted and corrupted humors out of the body). The 'fourth digestion' caused the four fluid humors to thicken and be converted into living tissue.4 Cockburn goes on to explain that moderate drinking "‘tis to be enjoyn’d for health’s sake; and I doubt not but this way of drinking will not only prevent, in a great measure, the sicknesses we have named, but even keep them from falling into the Dropsie [edema], Jaundice and Melancholia Hypochondriaca [depression, although accompanied with physical symptoms such as headaches and pains in the spleen, the organ thought to produce black bile which could caused melancholy)]."5

Thomas Tryon believed that fermented alcohols "are not only more spirituous and brisker in operation [than distilled alcohols], but also more cleansing and penetrating, if order and temperance be observed."6 This actually implies that all alcohols had some degree of cleansing and penetrating qualities, although he felt distilled drinks were less effective.

Tryon also suggested that 'old' alcohols "are far hotter in operation than new, and consequently more prejudicial to Health, especially to all such as are

Artist: John Taylor

Men Enjoying a Little Liquid Health, From A Brown Dozen of Drunkards (1648)

naturally subject to the Stone, Gravel, Gout, or Consumption, for it over-heats the Blood, and consumes the Radical Moisture"7. He further explains that 'old' fermented beverages and all distilled beverages contained a "harsh Fire, keen or sharp Spirit... which... Age turns [the qualities of fermented beverages] into heat, sharpness, and keenness" and was destructive to the body.8 However, he supported the moderate consumption of alcohols without such harsh qualities were "moderated, qualified, or allayed by the sweet imbraces of those friendly Virtues" found in newly fermented beverages.

Even the pirates commented on the health aspects of alcoholic beverages. After John Massey and George Lowther absconded with Royal African Company's Bumper Galley from Fort James in Africa, they wrote a petition explaining the reasons behind their action. One of their complaints about the Company concerned the poor victuals supplied by the local merchants at the fort. They had brought eight pipes of wine to the island for use of the men in the fort, but the merchants prevented them from delivering it. Massy and Lowther's petition protested that the merchants did this, "Notwithstanding [that] ye Company Ordered yt [that] Each Officer should have an Equall Allowance of Wine and yt Each Artificer [skilled craftsman posted to the fort] and Soldier should have a pint every Day. The country being so Unhealthy that it is impossible for White Men to Live in w[i]thout some Liquor to support nature."9

This notion is seconded by physician William Hughes, who noted that "all rational persons, who have ever been in the Indies, will conceive it so to be, by the frequent drinking of Rum, Brandy, and other strong and hot Spirits; which doth sufficiently prove, that if such strong liquors are good at any time, (as doubtless they are) they are best in Summer"10. Hughes goes on to argue that such 'hot' alcohols were less appropriate in cold winter, when the 'spirits' of the body were fixed. However, in 'hotter Regions', "of necessity Nature doth require a better supply [of blood and radical moisture, apparently forced out by 'hot' liquids] to maintain the internal heat."11 Pirates can't just make this all this health stuff up, after all.

1 Tobias Venner, Via Recta ad Vitam Longam, 1638, p. 43-4; 2 James Howell, Epistolæ Ho-Elianæ, 1726, p. 366; 3 William Cockburn, The Diseases of Seafaring Peoples, 1696, p. 71; "Digestion: Origin and Metabolism of the Four Humors", greekmedicine.net, gathered 2/3/2018; 5 Cockburn, p. 71; 6,7,8 Thomas Tryon, A New Art of Brewing Beer, Ale and other Sorts of Liquors, 1691, p. 15; 9 Ed Fox, “28. The petition of John Massey and George Lowther, from EXT 1/261, ff. 197-199", Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 133; 10 William Hughes, The American Physitian, 1672, p. 142; 11 Hughes, p. 142-3

Alcohol and Health - Alcohol-Based Medicines

Alcohol actually had an important place in healing as a medicine. In fact, it was medicine which introduced distilled alcohols to the public. While a variety of medicines contained alcohol (and two of them - Spirit of Wine and Rectified Spirit of Wine are basically types of brandy), there are three classes of medicines that appear in some of the sea surgeon's books which were often built on an alcohol base. These were cordials, tinctures and elixirs. Let's take a brief look at each.

Artist: Godfrey Kneller

Drinking a Cordial, Thomas Pelham-Holles Entertaining Henry Clinton (c. 1721)

Distilled 'cordial waters' were an important part of medicine during the golden age of piracy, often used by physicians and sea surgeons in treating patients. By the golden age or piracy, some of them had also made their way from the pharmacy into the homes of polite society as well. However, our interest here is in their medicinal applications.

Apothecary John Quincy's Lexicon defines cordials. "Whatsoever raises the Spirits, and gives sudden Strength and Chearfulness, is termed Cordial, or comforting the Heart."1 Quincy goes on to explain the cordial effect "is most: remarkable from spirituous Liquors... and this will be found to consist only in their Subtilty, and Fineness of Parts. ...the more spirituous any thing is which enters into the Stomach, the sooner a Person feels its cordial Effects"2. A little more explanation of this comment is necessary here. Many apothecaries believed that "distilled waters contained the subtle active ingredients of the drugs" while what was left behind by the heating process was "regarded as crude separations."3

Distillation has a long history in medicine. Distilling apparatus dates back to the beginnings of the Christian era.

Distillation Equipment Described By Zosimos of Panoplis in the Third Century

Third century Egyptian historian Zosimus described such devices based on the works of two chemists named Cleopatra and Mary the Jewess.4 Most historians agree that this apparatus was not used to distill and make alcoholic beverages, however.5 The writings of the Arabic physicians refer to distilling as a way to produce medicines, although their definition of distilling included a variety of methods including filtration, pressing oils and soaking herbs and plants in water to draw out their essence. Chemist and historian Robert Forbes noted that "no proof was ever found that the Arabs knew alcohol or any minderal acid in a period before they were discovered in in Italy" at the Salerno medical school.6 Tenth century Muslim physician Albucasis [Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi] provided instructions for distilling rosewater and vinegar in his manuscripts, although "there is nothing in it that applies to an essence proper, or especially to alcohol"7.

The Salerno School, Schola Medica Salernitan, From Avicenna's Canons

Following the 8th century invasion of Hispania, the Arabic ideas about medicine began to influence European medicine, particularly with the founding of the Salerno school, Schola Medica Salernitana. As a result, "Europeans became acquainted with Arabian scientific ideas, as well as with their methods, among others with the process of distillation and the utensils used in this process."8 Forbes says that "one of the earliest references to distilled alcohol is found in the writings of Salernus"9 who lived in Salerno between 1130 and 1160 and and is believed to be one of the founders of the Salerno school. Waters distilled from herbs and plants became an important part of European medicine beginning in the 13th century. "[T]he alchemists in the beginning of the fourteenth century were taken with such admiration for the discovery of alcohol that they likened it to the elixir of long life and the mercury of the philosophers."10 They began to expand the library of distilled medicines.

With the arrival of chemical methods promoted by Swiss physician Paracelsus in the 15th and 16th centuries, pharmacy was separated from the more general medicine and apothecary shops were established where distilled

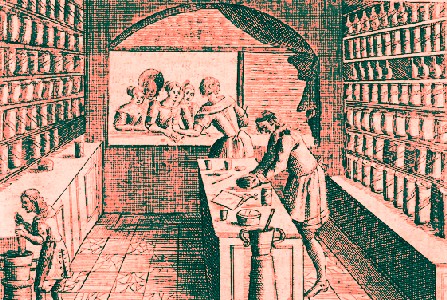

Artist: Caspar Luyken -

Apothecaries Making Medicines (1695)

medicines could be made in a laboratory setting.11 From here, the number of distilled cordial waters expanded, becoming an established part of medicine. They were an essential part of the sea surgeon's chest during the golden age of piracy; there are twenty-eight distilled waters included in the sea surgeon's dispensatory, which includes all the medicines recommended by sea surgeons John Woodall, John Moyle and John Tweedy. (The complete list of medicines in the sea surgeon's dispensatory can be found here.)

It must be noted that there were two types of distilled waters: simple and compound. Simple waters were those made by combining water with herbs, plants and other natural ingredients in the still in an attempt to refine and purify the essence of the raw materials. Compound waters were those made by distilling the ingredients combined with alcoholic spirits.12

There are twenty-nine distilled waters in the sea surgeon's dispensatory: Aqua Absinthi (Wormwood Water), Aqua Angelica, Aqua Anisi, Aqua Cardui Benedicti (Water of Blessed Thistle), Aqua Celestis, Aqua Cinamomi (Cinnamon Water), Aqua Cordial Fridga Saxony, Aqua Cychory (Succory Water), Aqua Epidemica (Plague Water), Aqua Falopy, Aqua Foneniculi (Fennel Water), Aqua Fortis Simplex (Strong Water), Aqua Hungarica (Rosemary Water), Aqua Limoniorum (Lemon Cordial), Aqua Melissæ Simplex, Aqua Menthæ, Aqua Mirabilis, Aqua Odifera (Sweet Water), Aqua Papaveris Comp (Poppy Water), Aqua Peoniæ Comp, Aqua Plantaginis (Plantane Water), Aqua Rosarum Album (White Rose Water), Aqua Rosarum Damask, Aqua Rosarum Rubrum (Red Rose Water), Aqua Sassafras, Aqua Stiptica, Aqua Theriacalis (Treacle Water), Aqua Viridas (Green Water), Argentum Vivum (Mercury) and Dr. Steevens Water.

Artist: Wolfgang Helmhard von Hohberg

An Apothecary Shop, From Georgica Curiosa Aucta (1697)

Five of the listed twenty-nine distilled waters are simple distillations, while the remaining twenty-four are compound, being distilled using a variety of alcohols including Spanish wine, Canary wine, white wine, strong waters (unnamed alcohols - typically wine or brandy), spirit of wine (both common - distilled once - and rectified - distilled several times) and wine vinegar.13 Although they were distilled, most of these drinks would probably have had a fairly low alcohol content, in the range of fifteen to thirty percent.14 (This is based on modern cordials, now called liqueurs. However, since alcohol content measurement was still fairly primitive at this time any number is really just a guess.) Some of them were definitely stronger than others. When treating a flux (diarrhea or dysentery) Sea surgeon John Woodall advised administering "good Aqua vitæ, or some strong cordiall waters, if you see there bee cause to comfort and warme"15. Aqua vitae is distilled wine or brandy.

Another alcohol-based medicine in use at this time was the tincture. Quincy says in his medical dictionary that a tincture is "any Liquor saturated with Ingredients of any kind"16. Physician Steven Blankaart

Offering a Tincture, From an Ad for Dr. Roch's Tincture (1738)

defines it as "an Elixir, the Extraction of the Colour, Quality, and strength of anything"17. Writing some time after the golden age of piracy, physician George Wallis explains that "Tinctures differ from distilled waters, because waters take out only the lighter parts that will ascend in vapour [during distillation]; but tinctures take up all such parts as are capable of being suspended in a menstruum [solvent liquid]."18

Whether or not a tincture is alcohol-based obviously depends on the menstruum used to make it. There are six tinctures found in the sea surgeon's dispensatory and four of them have a distilled alcohol base (spirit of wine). These include Tinctura Balsamica, Tinctura Castorei, Tinctura Myrrhæ and Tinctura Piperis Stomachica. Alcohol-based tinctures tend to have somewhat higher alcohol-content than waters; modern tinctures are estimated to contain around twenty-five to sixty percent alcohol.19 As mentioned, the sea surgeon's dispensatory is based on lists of medicines recommended by three sea surgeons: John Woodall, John Moyle and John Tweedy. However, Tweedy's list is a standalone bill of medicines created to stock a privateering voyage undertaken in 1743. There is no supporting information to explain how, why or when he used them. However, two of the tinctures - Tinctura Balsamica and Tinctura Myrrhæ - are found in Moyle's book where there is more information. The first does not have an alcohol base while the second does.

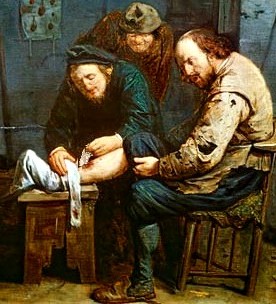

Artist: David Ryckaert (1638)

Moyle says that Tincture of Myrrh and Tincture of Balsam "are mostly preferred at Sea, and indeed are great and approved Vulneraries."20 Vulneraries are used to heal external wounds so their ability to intoxicate here is actually irrelevant. Moyle mentions using either one or the other to treat the exposed bone after amputation21, in gunshot wounds22, penetrating wounds of the back23. He several times suggests that they can be used interchangeably, so alcohol content is clearly not important here.

Elixirs are very similar to tinctures. Physician Wallis goes so far as to state that "elixirs contain the active parts of more than one ingredient, so are compound tinctures."24 He does state that "An elixir is more saturated than a tincture, hence not so clear."25

There are but three elixirs in the sea surgeon's dispensatory -Elixir Proprietatis, Elixir Vitæ and Elixir Vitrioli, of which only the last two contain alcohol, being based on spirit of wine. None of them are found in recommended medicines mentioned by either sea surgeons Woodall or Moyle, only appearing in Tweedy's Bill of Materials.

1,2 John Quincy, "Cordial", Lexicon Physico-Medicum, 1726, p. 98; 3 Eduard Guildemeister & Fredrich Hoffman, The Volatile Oils, Translated by Edward Kremers, 1900, p. 19; 4 Marcellin Pierre Eugène Berthelot, “The Discovery of Alcohol and Distillation”, Popular Science Monthly, Volume 43, May 1893, p. 88; 55 R. J. Forbes, A Short History of the Art of Distillation, 1970, p. 28; 6 Forbes, p. 32; 7 Berthelot, p. 92; 8 Guildemeister & Hoffman, p. 20; 6 Forbes, p. 57; 10 Berthelot, p. 94; 11 Guildemeister & Hoffman, p. 21; 12 Nancy Cox and Karin Dannehl, “Aqua”, Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities 1550-1820, 2007, gathered 2/4/18; 13 For more on the processes used to distill various waters, see the Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory article, page 18; 14 "Liqueur", wikipedia.com, gathered 2/6/18; 15 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 210; 16 Quincy, "Tincture", p. 449; 17 Steven Blankaart. "Tinctura", The Physical Dictionary, 1702, p. 307; 18 George Wallis, "Tinctura", A New Medical Dictionary, 1795, p. 699; 19 "Tincture", wikipedia.com, gathered 2/6/18; 20 Moyle, Chirugius, p. 17; 21 Moyle, Abstractum, p. 35; 22 Moyle, Chirugius, p. 71-2 & 76; 23 Moyle, Chirugius, p. 81; 24 Wallis, "Tinctura", p. 699; 25 Wallis, "Elixir", p. 321

Alcohol and Health - Alcohol-Based Medicines: Use of Cordial Waters by Sea Surgeons

Medicines at the Ready, From Medizinische

Annalen Fur Aerzte, By Johann Frietze (1781)

Cordial waters were an essential part of the sea surgeon's practice. Both sea surgeons John Moyle and John Atkins advised having them on hand when the ship was preparing for battle when the ship's surgery was about to get hectic. Moyle recommended the ship's surgeon ready "cordials to give when men faint" while waiting for the surgeon to treat them.1 (During bloody battles, the sailors could be waiting quite a while.) Atkins is a little more expansive, explaining that to the patients who were waiting while the surgeon treated other wounded, "we must give Cordials at this Time; and Wine has, in my Opinion, the Preference; because we are to quench Thirst, as well as refresh the Spirits."2

Cordial waters were also prescribed to treat a variety of health problems by sea surgeons. The majority of them come from two books by John Moyle - Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ and Chirugius Marinus. Many of the other references come from John Woodall's the surgions mate and John Atkins' The Navy Surgeon. Administration of cordials is fairly well divided between the two types of medical treatment the sea surgeon handled: mechanical surgical operations and internal health problems.

John Moyle frequently used cordials in surgical operations, typically prescribing a dram3 or spoonful4, which is about the same amount.

Artist: Jan van der Straet - Patient

Drinking (1600)

He was cautious about giving patients more alcohol either before or after a surgical operation, warning his readers to "have a care of [giving the patient] too much, less it [the cordial] inflame him, and make his blood more fluid: And have an Eye [keep a lookout] lest his Messmates come with their bottle, and prejudice him with their kindness, as I have sometimes seen"5. Some modern studies do indeed support the idea that moderate alcoholic intake can act as an anti-coagulant, so Moyle was on firm ground in his statement, although there are a wide variety of other factors that also affect coagulation of blood and excess consumption obviously leads to other problems.6

Despite what popular media sometimes portrays, the purpose of the cordial dram wasn't to get the patient drunk or act as some sort of intoxicating anesthetic so that he wouldn't feel the operation; it was given for the opposite reason. Moyle repeatedly mentions giving his spoonfuls of cordial while the patient waiting to for the surgeon to be free or an arduous operation to begin in order "to keep up his Spirits"7, "to cherish him"8 and "revive his spent spirits"9. This is similarly implied by German military surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purrman, who recommends before performing an amputation to "first give the Patient a good Cordial, and encourage him by proper words, to suffer with patience what will conduce to his future well-being."10

The mechanical surgical operations where sea surgeons suggested giving cordials include trepanning (cutting a hole in the skull to relieve pressure on the brain)11, treating gunshot wounds12and incised wounds13, restoring dislocated joints14, amputating limbs15 and relieving complications from amputations16.

Artist: Howard Pyle (1893)

The internal health problems where cordials were used were normally the purview of physicians, but, at sea there were usually no physicians handy so the surgeon had to treat such cases. The sea surgeons books mention giving cordials when treating near drowning cases17, rheumatism18, calentures or 'tropical fevers'19, colic (pain in the abdomen)20, syphilis21, measles and small pox22, pleurisy23 and fluxes (diarrheas and dysenteries).24

For fluxes, both Moyle and Woodall agree that stronger cordials were preferable. Woodall recommends "good Aqua vitæ, or some strong cordiall waters, if you see there bee cause to comfort and warme"25. Moyle explains that when treating dysentery "good Cordials are of great use, for men in a little time grow extream faint"26 because the problem "takes away the strength of the Patient, and brings him weak and faint; therefore there must be choice Cordials often given him to keep up his Heart, and dissipate the malign Vapours and Atoms that arise from the putridity of the Ulcerations"27.

1 John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, 1686, p. 22; 2 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 149; 3 Moyle, Abstractum, p. 24, 28 & 43; 4 John Moyle, Chirugius Marinus: Or, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 52, 70, 80 & 108; 5 Moyle, Abstractum, p. 28; 6 Kenneth J. Mukamal, Praveen P. Jadhav, et. al., "Alcohol Consumption and Hemostatic Factors", National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse, www.niaaa.nih.gov, gathered 2/7/18; 7 Moyle, Abstractum, p. 24 & Moyle, Chirugius, p. 108; 8 Moyle, Chirugius, p. 70; 9 Moyle, Chirugius, p. 98; 10 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, 1706, p. 210; 11 Moyle, Chirugius, p. 108; 12 Moyle, Chirugius, p. 70; 13 Moyle, Chirugius, p. 80 & Moyle, Abstractum, p. 55; 14 Moyle, Abstractum, p. 43; 14 Moyle, Chirugius, p. 52 & Moyle, Abstractum, p. 24 & 28, John Moyle, Memoirs: Of many Extraordinary Cures, 1708, p. 119 & John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 176; 16 Atkins, p. 134; 17 Moyle, Chirugius, p. 98; 18 Moyle, Chirugius, p. 220; 19 Woodall, p. 210, Moyle, Abstractum, p. 117 & Moyle, Chirugius, p. 162; 20 Jeremy Roch, from Bruce S.Ingram, Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 122-3, Moyle, Abstractum, p. 110 & Woodall, p. 240; 21 Moyle, Memoirs, p. 88-9; 22 Moyle, Abstractum, p. 125; 23 Moyle, Chirugius, p. 230; 24 Woodall, p. 248, Moyle, Abstractum, p. 117 & Moyle, Chirugius, p. 162; 25 Woodall, p. 248; 26 Moyle, Abstractum, p. 117; 27 Moyle, Chirugius, p. 162