Booze, Sailors & Health Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Next>>

Booze, Sailors, Pirates and Health In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 10

Alcohol - Rum

“The cheife fudling they make in the Iland [of Barbados] is Rumbullion, als Kill-Divill, and this is made of sugar cones distilled a hot hellish and terrible liquor”. (Giles Silver, “Letter from Barbadoes By the Way of Holland Concerning the Condition of Honest Men There, 9th Aug. 1651”, Colonising Expeditions to the West Indies and Guiana, 1623-1667, Vincent Todd Harlow, 1925, p. 46)

Photo: P. Biswas - Bottle of Captain Morgan Rum

You can hardly talk about pirates without conjuring an image of rum, thanks in large part to the marketing efforts of the Seagram's corporation and (after Seagram's sold the brand) the Diageo conglomerate.

There is a lot of discussion over the origin of the term 'rum', probably because it has been called by so many names since it was first distilled in the Caribbean in the early 17th century. The authors of Alcohol and Temperance in Modern History give one of the most thorough explanations of this beverage's name.

Cachaça is the most common name for distilled alcohol mode from sugarcane in Brazil. In the French Caribbean taifa, eau de vie de canne, and clarin all refer to alcoholic beverages made from sugarcane. In the Spanish Americas, aguardiente de caña and chingurito have been used. Kill devil referred to distilled sugarcane-based alcoholic beverages in the early British Caribbean, and this name transferred to the French as guildive.

‘Rum’ eventually became the most common term for a distilled sugarcane-based alcoholic beverage outside of Brazil. It originated in the British Caribbean in the seventeenth century and derived from the English word ‘rumbullion’.1

Artist: J. M. Marchand

Pirates Toasting, From Sir Henry Morgan, Buccaneer (1903)

What rumbullion means isn't clear, at least according to the Oxford English dictionaries website2, although a variety of books (none of which your author can find that were older than 1885) will tell you it's an old Devonshire word meaning 'a great tumult.' There are a number of rather involved and tangled theories about what the word 'rum' might be derived from, but these mostly make for tedious reading that have nothing to do with the beverage itself.3 Before leaving the origins of the word, it it worth noting that the French on Martinique adopted the word 'rum' from the English in the mid-17th century, which was eventually changed to 'rhum' for some strange reason. Ian Williams tartly suggests that the 'h' was added by French Encyclopediasts "probably out of sheer pedantry to make it seem apothecary-like."4 With that, I promise to say no more about the origins of the word 'rum'.

As for the origins of the drink itself, it was first made by indentured servants (sometimes called

Photo: Wiki User postdil -Sugar Cane Field, St. Lucy, Barbados

'white slaves') on the Caribbean island Barbados from the leftovers of sugar production. Williams notes that many of these servants were from Ireland and Scotland and so were familiar with the distillation of malted grain whisky (albeit, not the smooth product we are today familiar with) and had a taste for the product of their homeland.

Any exiled Celt who had dealt with malt to make a mash for a still would not need to be an Einstein to make the connection with molasses, not least on an island like Barbados, where traditional cereal production was insufficient for food, let alone brewing. So the odds are high that it may well have been an aesthete Celt, desperate for a decent drink, who decided that all those spirits needed releasing from their distasteful, wet, and murky brown shroud.5

Most of the rum consumed during the golden age of piracy was made in the Caribbean. Beginning

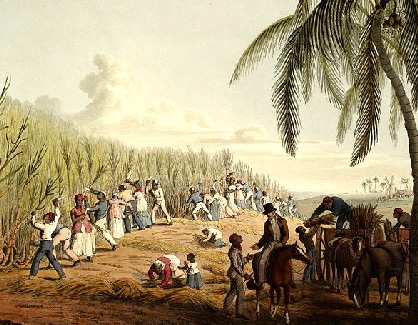

Artist: William Clark

Cutting the Sugar Cane, From Ten Views of the

Island of Antigua (1823)

in the early/mid seventeenth century Barbadoes and French Martinique began rum production using the waste product created in the processing of sugar. At first, the distillers used "scum, the material skimmed off during the sugar boiling process. By the late seventeenth century, molasses, the material that dripped from sugar molds during the sugar curing process, became a primary ingredient in rum making."6 This gave rum an advantage over some of the other distilled products which used things that would otherwise serve as food (such as whiskey and gin) meaning "there [was] no danger of its production being restricted in times of drought."7 It didn't even interfere with the regular operation of the sugar-making process. Physician Hans Sloane explained that the molasses and scum were mixed with water and was "carried into the Distilling-house; where, after fermentation, when it begins to subside, in the night time distil it till thrown into the Fire it burns not: this in the day time is Re-distilled, and from Low-Wines is call'd high Wines or Rum."8

Writing in 1673, Richard Ligon, half-owner of a sugar plantation in Barbados, drew a diagram of his sugar-making house with an explanation of its workings, which he labeled

Richard Ligon's Sugar Refinery and Distilling Room

From A True and Exact History of Barbadoes (1673)

"The Platforme or Superficies of an Ingenio [refinery], that grinds or squeezes the Sugar". Ligon was nothing if not detailed; his diagram has a scale along the right side as well as letters on every post, wall, window and door in the buildings. He even numbers the steps in the staircases! Most of the diagram and Ligon's explanation are concerned with making sugar. The blue descriptions on the diagram summarize each rooms' purpose although further details of the process are beyond the scope of this article. The distilling room where rum was made is highlighted in pink in the upper right corner of the plan. The relevant parts are lettered in red, which Ligon explains:

Q. ...besides the [boiling] Coppers, there are made small Gutters, which convey the skimmings of the three lesser Coppers, down to the Still-house, whereof the strong Spirit is made, which they call kill-devil, the skimmings of the two greater Coppers are conveyed another way, as worthless and good for nothing.

...

W. The Still House

X. The Cistern that holds the skimmings (in the middle of the pink room), till it bagine to soure, 'till when, it will not come over the helme [the still head, as shown in the diagram of a still on the previous page].

Y. The two Stills in the Still-house.9

Contemporary historian John Oldmixion also briefly explained the process of making rum in 1708:

...the Dregs of the Juice [molasses], the Skimmings of the Copper, and the Droppings of the Pots [in the storehouse] ... are carry'd to Cisterns and Backs, where they ferment; and are then drawn by Pipes into the Stills, in a House adjoining to the former, which is call'd the Distiling-House. Here they are first distill'd, and then rectify'd into the Spirit we have spoken of, call'd Rum.10

Ligon says that the first distilling "is a small [low-alcohol content] Liquor, which we call low-wines, which Liquor

Distillery, From Denis Diderot's Encyclopédie (1763)

we put into the Still, and draw it off again; and of that comes so strong a Spirit"11, which agrees with Oldmixon's description.

Rum was distilled in several places during the golden age of piracy. Both Ligon and Oldmixon were talking about distilling in Barbados, which was the birthplace of English rum, probably starting in the first quarter of the seventeenth century. The French began distilling rum sometime after sugarcane was introduced to the island of Martinique in 1640. It was described in 1667 by Père du Tertre in his book Histoire générale des Antilles habitées par les François: "One of the most widely used [by products of sugarcane mentioned in du Tertre's book] is a juice called 'Vésoü' which properly fermented and distilled gives "une boisson qui se débite fort bien dans les isles" (a beverage widely produced and consumed in the islands)."12

The English captured Jamaica from the Spanish in 1655, which gave them a whole new island for rum production. Jamaica already had established sugar plantations, so it was simply a matter of setting up the plantation to distill molasses to produce rum if they weren't already doing so. As a result, as Ian Williams explains, "Barbados lost its primacy in rum-making, which went to Jamaica, where the wash included the skimmings of the sugar boilers which were added to the molasses. Otherwise wasted, these skimmings also added to the distinctive flavor of Jamaica rum"13.

Artist: William Clark

Curing-house and Distillery, From Ten Views of the

Island of Antigua (1823)

The spirit was also being distilled on the North American continent. “Starting in the mid-1600s, sugar, and molasses were exported from the West Indies to New England where the colonists made their very own variety of rum."14 Williams says that New England was an ideal place for distilling rum, "with its superior technical and metalworking skills to make the stills and its ample supply of timber for fuel and cooperage."15 However, he notes that the resulting product "did not have the color or the aroma of the West Indies rum, which was why anyone who could afford it drank the Caribbean import. Local rum's biggest advantage was that it was much cheaper."16

The price of rum had much to do with its use and spread in the West Indies and colonies. Historian Alice Morse Earle explained, "In 1673 Barbadoes rum was worth 6s. a gallon. In 1687 its price had vastly fallen, and New England rum sold for 1s. 6d. a gallon. In 1692 2s. a gallon was the regular price. In 1711 the price was 3s. 3d."17 Even with the decrease in price, making rum was a lucrative business. As Williams points out, the British sugar planters "could use the by-product of their sugar production as a revenue source almost as lucrative as the sugar itself"18. Rum was clearly a business worth being in during the golden age of piracy.

Richard Lignon said that the sugar-makers sold rum to those on the island without sugar plantations, who "drink excessively of it, for they buy it at easie rates; half a crown a gallon was the price, the time that I was there"19. Ligon also advised that it was "a commodity of good value in the Plantation; for we send it down to the Bridge, and there put it off to those that retail it. Some they sell to the Ships, and is transported into forraign parts, and drunk by the way."20 Very little, if any, of this rum would have been shipped in bottles; "Wooden casks were the shipping containers of their day."21

Like other alcohols, rum was the subject of some political intrigue, although not on as grand a scale as some of the other alcohols during the period. Most significantly to the British was the taking of Jamaica and the production of inexpensive rum. This prompted a

Artist: Sir Godfrey Kneller - Samuel Pepys (1689)

request which changed the use of alcohol within the Royal Navy for three hundred years. Although the request itself has been lost, the response has not. Secretary of the Navy Samuel Pepys sent a letter to a Mr. Waterhouse, apparently a merchant on the island, giving him permission "to supply King James's ships at Jamaica with Rumm instead of Brandy, he takeing care that the good or ill effects of this proof, with respect as well to the good Husbandry thereof as to the Health and Satisfaction of our Seamen, be carefully inquired into by you and reported to us within a yeare or two (or sooner if you find it necessary for our further satisfaction in the same)."22 Whatever the effects on health, it seemed to satisfy the navy sailors, as they drank (and celebrated with) it until 1970. (Although, as has already been noted, shortly after the golden age of piracy the rum began to be dramatically watered down in 1740 under the orders of Vice-Admiral Edward Vernon, and was likely being watered down by some individual ship's commanders even before then.)

Much of the larger world political governing of rum came from France. Due to rum's low cost, it was replacing brandy as the alcohol of choice for commerce. "By 1679, French slave traders were already complaining that the brandy they had formerly used in trade for slaves in Africa had been flooded out by cheaper rum, and one recorded that a large bull was bought for one pint of spirit in 1697 in Senegal."23 As a result of this, "[r]um exports were banned [to France] in 1715 to protect native brandy."24 However, this did little to curb the demand for rum or prop up the sagging demand for brandy outside of France.

Artist: William Clark

Loading Casks at the Distillery, From Ten Views of the

Island of Antigua (1823)

The English were selling as much rum as they could manufacture - rum permeated the West Indies and colonies. "[B]y the late seventeenth century, Barbados was producing about 1 million U.S. gallons (3.785 million liters) annually and Martinique was probably producing about half that amount. …The high cost and limited availability of imported European alcoholic beverages led colonists to search for local alternatives."25 This is pretty significant, given that the SAGE Encyclopedia of Alcohol says "the capacity of early Caribbean stills was small – perhaps 100 to 300 gallons."26

In fact, it was the French laws prohibiting their colonies from exporting rum combined with the high price of Caribbean rum outside of the Caribbean which gave the American colonists their foothold in rum production. Because the British Caribbean sugar plantation owners were selling all the rum they could produce, they had no incentive to send molasses to the colonies to make rum. Lacking a supply of raw materials, the colonists turned to the sugar plantation owners on the French Caribbean islands. The French rum "was not as good as the British islands' products, and with the ban on exports there was no incentive for the planters to improve the quality. That left the planters with vats of surplus molasses from their sugar production that they had no legal market for."27 The French molasses would otherwise have been wasted, so they sold it inexpensively to the colonists, who then were able to produce and sell their rum less expensively than the English Caribbean distillers.

Artist: Major Joan Blaeu - Dutch Sugar Plantation, Blaeu Atlas vol 11 (1662-5 )

This allowed them to outbid the English Caribbean island traders for slaves "on the African coast, where rum was as good as currency. French molasses in 1691 was, for example, 60 percent to 70 percent cheaper than its British competition."28

Opinions on the flavor of the rum varied. Contemporary historian John Oldmixon wrote in 1708 the rum would be good "were it not for a certain Twang or Hogo that it receives from the Juice of the Cane, 'twould take place next to French Brandy; for 'tis certainly more wholsome"29. Modern mixologist David Wondrich explains that the word 'hogo' was the English corruption of the French haut gout referring to a taste of slight decay that was encouraged in game meats during this time. Wondrich says that in reference to rum, it was a "strong and somewhat offensive molasses-like flavour" found particularly in unaged rums.30 (Few rums during this time would have been aged. It sold too fast to bother with aging.) Wondrich suggests this vegetative flavor was an acquired taste. Oldmixon added that 'kill-devil' was "a mean Spirit, that no Planter of any Note will now deign to drink; his Cellars are better furnish'd."31

Photo: Linus Bohman - A Glass of Rum

Writing in 1731, Physician Peter Shaw explained that the rum of that time contained

the natural flavour, or essential oil of the Sugar-Cane... The unctuous [oily] flavour of Rum, is often supposed to proceed from the large quantity of fat used in boiling the Sugar: which fat indeed, if coarse, will commonly give a disagreeable, nidorous, or oily flavour to a Spirit; as I have found by experience: But Rum has its specific and natural flavour from the Cane.32

This, again, sounds like a reference to the earthy, vegetative 'hogo' taste to which Oldmixon refers. Like Oldmixon, Shaw does not seem to have been a fan of this flavor. He goes on to suggest that it can be removed "by duly throwing out its Oil... [which will bring it] to a fine tasteless Spirit, [and] will give it a flavour bordering very near upon that admired in Arrac."33

Writing about a visit to São Tomé in 1694, captain Thomas Phillips of the Royal African Company's ship Hannibal said, "They make store of rum here, but ’tis sad stinking raw stuff."34 Phillips seems to suggest this was the fault of the sugar cane grown there, explaining, "The sugar that is made here is very coarse and dirty, and seldom well cured"35. He later blamed an illness he called 'the white flux' on "the unpurg’d black sugar, and raw unwholesome rum they [his sailors] bought there, of which they drank in punch to great excess"36. In an attempt to stop the illness, he threw all the São Tomé sugar and rum he could find on the ship overboard.

This is clearly not the rum produced by companies today. Wondrich suggests that most modern rums, which are "as white and pleasantly inoffensive as vodka, or as sweet, mellow and woody as bourbon" would not be accurate representatives of the hogo-tinted rums of the period.37 (For those interested, Wondrich gives several suggestions for modern rums which approximate this flavor on page 76 of his book under the heading Pirate Juice.)

1 Jack S. Blocker, Jr., David M. Fahey, and Ian R. Tyrrel, eds., “Rum”, Alcohol and Temperance in Modern History, 2003, p. 525; 2 "rumbullion", en.oxforddictionaries.com, gathered 12/9/17; 3 For those interested, I recommend the blog entry "The Rum History of the Word 'Rum'", by Anatoly Liberman; 4 Ian Williams, Rum, 2006, p. 6; 5 Williams, p. 42; 6 Blocker, Fahey, and Tyrrel, eds., p. 525; 7 Henry Jeffreys, Empire of Booze, 2016, p. 77; 8 Hans Sloane, A voyage to the islands of Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 1, 1707, p. lxi; 9 Richard Ligon, A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbadoes, 1673, p. 123; 10 John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, Vol. 2, 1708, p. 152; 11 Ligon, p. 92-3; 12 "Rhum Agricole: Martinque Rum", rhum-agricole.net, gathered 10/10/17; 13 Williams, p. 210; 14 “History of Spirits in America: The Spirit of America--Rum?”, discus.org, gathered 12/6/17; 15,16 Williams, p. 65; 17 Alice Morse Earle, Stage-coach and Tavern Days, 1900, p. 102-3; 18 Williams, p. 265; 19,20 Ligon, p. 93; 21 Williams, p. 215; 22 Samuel Pepys, Secretary to the Navy, 3 March 1688, Cited in Peter Macinnis, Bittersweet: The Story of Sugar, 2003, p. 97; 23 Williams, p. 90-1; 24 Henry Jeffreys, Empire of Booze, 2016, p. 78; 25 Blocker, Fahey, and Tyrrel, eds., p. 525; 26 Scott C. Martin, “Rum”, The SAGE Encyclopedia of Alcohol, 2014, not paginated; 27 Williams, p. 123; 28 Williams, p. 123-4; 29 John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, 1708, p. 152; 30 David Wondrich, Punch, 2010, p. 74; 31 Oldmixon, p. 122; 32 Peter Shaw, Three Essays in Artificial Philosophy, 1731, p. 140; 33 Shaw, p. 141; 34,35 Thomas Phillips, 'A Journal of a Voyage Made in the Hannibal', A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol. VI, Awnsham Churchill. ed., p. 233; 36 Phillips, p. 236; 37 Wondrich, p. 74

Rum Use Among Period Sailors

Rum was widely used as a drink the Caribbean, although it was not typically drunk straight despite what the popular portrayal of sailors and pirates suggests. Ian Williams points out, "In its early days in the mainland American colonies, rum was more likely to be drunk in a punch of some

Artist: Samuel Scott - Loading Casks Into a Boat (18th century)

kind than as raw spirits."1 Point of fact, it is found as a straight drink in only one naval citation2, two merchant and privateer citations3 and sixteen pirate citations4.

The single navy citation is the order from Pepys allowing the navy to use rum in place of brandy in the Caribbean, so rum is clearly underrepresented in the sample of periodicals used for this article, probably because most of the naval books used are from places outside of the West Indies.

The pirate data includes the taking of small quantities of rum from ships which do not explicitly mention the pirates drinking the rum. Given the small quantities of rum mentioned, however, it seems likely that this rum was not for trade or sale, but for consumption.

A complicating factor in this data is figuring out which references in the period sea literature refer to rum being drank straight and which refer to it being used in punch. (Punch is discussed in detail in the next section.) Some of the citations directly state that the rum mentioned in them was used to make punch, while others only hint at it by saying that the sailors had rum along with one of two other items used in the making of punch, specifically sugar and/or lime juice. Accounts with punch ingredients that do not specifically mention punch are not been included in the above figures. They include eighteen pirate citations5.

Most of the passages counted above simply mention rum, which leaves us with only a few interesting stories about its use by sailors.

'Stranded'

One involved the group of pirate mutineers in the Bahamas. They had taken the schooner Bachelor's Adventure and the sloops Mary and Lancaster which had been sent from the reformed Bahamas' base by Woodes Rogers on a trading mission. Stranding the ships' legitimate crew on Green Key, the mutineers left to go on the account. Unfortunately for them, most of the mutineers were captured by the Spanish Garda Costa. The Spaniards sent the forced men, stranded officers and wounded back to Providence, Bahamas. However, some of the pirates managed to escape, making their way to Long Key.

On hearing the story of their capture by the men who had been released by the Spanish, Rogers sent Benjamin Hornigold and Richard Turnley in a sloop to capture the pirates who had managed to escape to Long Key. When this sloop arrived, the escaped pirates thought it was a merchant, so the majority hid to ambush the men of the sloop while two or three called out to them from the shore that they were shipwrecked.

The sloop's boat was sent ashore "with two Bottles of Wine, a Bottle of Rum, and some Biscuits... which he [a man pretending to be the sloop's master] said he brought ashore to comfort them, because his Men told them they were cast away."6 The pirates, still thinking him a merchant, asked to be put on board. They were taken a few at a time back to the ship and led to the ship's cabin "where, to their Surpize, they saw Benjamin Hornigold, formerly a Brother Pyrate; but what astonished them more, was to see Richard Turnley, whom they had lately marooned upon Green Key; they were immediately surrounded by several with Pistols in their Hands, and clapped in Irons."7 What is most interesting from an alcohol point of view, was that the rum was brought in bottles. However, it is likely this was done for convenience; Hornigold's men probably either filled the bottle from a cask on the ship or in Providence.

1 Ian Williams, Rum, 2006, p. 61; 2 Samuel Pepys, Secretary to the Navy, 3 March 1688, Cited in Peter Macinnis, Bittersweet: The Story of Sugar, 2003, p. 97; 3 Thomas Phillips, 'A Journal of a Voyage Made in the Hannibal', A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol. VI, Awnsham Churchill. ed., p. 233 & Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 52, George Roberts, The four years voyages of Capt. George Roberts, 1726, p. 49, 57 & 63, 4 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 77, 86, 222, 293, 374, 595 & 639, Ed Fox, “2. William Phillips The Voluntary Confession and Discovery of William Phillips, 8 August, 1696. SP 63/358, ff. 127-132”, Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 23, Fox, “63. Adam Baldridge: Deposition of Adam Baldridge, 5 May, 1699…", Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 347, Fox, “67. Prices of Pirate Supplies: A List of the Prices that Capt. Jacobs sold Licquors and other Goods att, at St. Mary’s, 9 June, 1698…”, Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 362, “The Trials of Five Persons for Piracy, Felony and Robbery”, 1726, p. 10, “The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet”, 1719, p. 46; 4 Captain William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea and the Slave Trade, 1734, p. 272-3; 5 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 77 & 221-2, Fox, “2. William Phillips The Voluntary Confession and Discovery of William Phillips, 8 August, 1696. SP 63/358, ff. 127-132”, Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 23, Fox, “21. The Whydah survivors tell their stories”, Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 86, Fox, “43. Henry Treehill, from The Information of Henry Treehill, 21 March, 1724. HCA 1/55, ff. 64-68”, Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 202 & 203, Fox, “67. Prices of Pirate Supplies: A List of the Prices that Capt. Jacobs sold Licquors and other Goods att, at St. Mary’s, 9 June, 1698…”, Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 362, Johnson, History of the Pirates, p. 155 & 183, “The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet”, 1719, p. 13 & 49, Applebees Original Weekly Journal, 1-21-21, Weekly Journal or British Gazetteer, 8-25-22, American Weekly Mercury, Vol 3, 1721-1722, The Colonial Society of Pennsylvania, 1905, p. 75, Daily Post, 10-6-11, Issue 943, Weekly Journal or Saturdays Post, 12-14-17, Issue 53; 6 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 639; = 7 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 640

Rum and Health

From a health perspective, most of the usual commenters cited in this article are silent. None of the sea surgeons suggested its use in their operations or healing. This may have been because rum was a relatively new drink and, particularly at the beginning of the golden age of piracy, somewhat confined to the Caribbean.

Photo: Flickr User Beck

Some Animal Liver With Your Rum, Then?

However, John Oldmixon had some things to say related to health. He mentioned that it was more wholesome than brandy, as stated previously, adding "'tis much better than Malt-spirits, and the sad Liquors sold by our Distillers."1 Although he was no medical man, Oldmixon advised, "Rum does not so soon destroy the radical Moisture and Digestion of the Stomach, as French Brandy does; whose thin, hungry Leanness is prov’d, by putting a raw Piece of Flesh into it, where it will be eaten, and perish much sooner than a like Piece put at the same time into Barbadoes Brandy or Rum."2 Physician Hans Sloane cites a similar experiment performed in Jamaica, where "any Animals Liver put into Rum grows soft, and not so in Brandy, whence they argue this last less wholesome than that, but their Experiment, if true, proves no such thing. I think it may be said to have all good and bad qualities of Brandy, or any fermented or vinous Spirit."3 Obviously there was a reason you went to school for medicine.

Richard Ligon also offered some comments on the healthiness of rum. He observed that rum could be good when drunk in moderation, because "strong drinks are very requisite, where so much heat is; for the spirits being exhausted with much sweating, the inner parts [organs] are left cold and faint, and shall need comforting, and reviving."4 Ligon supports this in a couple place in his book. He notes that when the slaves on his plantation "find any weakness or decay in their spirits and stomachs, and then a dram or two of kill-devil revives and comforts them much."5 He later adds to this substantially, explaining:

[T]his drink is of great use, to cure and refresh the poor Negroes, whom we ought to have a special care of by the labour of whose hands, our profit is brought in; so is it helpful to our

Christian [indentured] Servants too; for, when their spirits are exhausted, by their hard labour, and sweating in the Sun, ten hours every day, they find their stomacks debilitated, and much weakned in their vigour every way, a dram or two of this Spirit, is a great comfort and refreshing to them.6

This actually does not wander far off the medical reservation; 'cordials' were alcoholic drinks with herbs infused in them that were given by the medical profession to strengthen and 'cherish' the organs during treatment.

Ligon goes on to explain that "the immoderate use of them [alcoholic spirits], over-heats the body, which causes Costiveness, and Tortions in the bowels

Artist: Thomas Murray - Sir Hans Sloane

[diarrhea/fluxes]; which is a disease very frequent there; and hardly cur'd, and of which many have dyed"7. Ligon also notes that "the people drink much of it, indeed too much; for it often layes them asleep on the ground, and that is accounted a very unwholsome lodging."8 Although this can't be blamed on rum alone, the idea is echoed in the period medical literature by sea physician William Cockburn.

Having been in both Barbados and and Jamaica in the late seventeenth century gave physician Hans Sloane an opportunity to observe and comment on the health benefits of rum from a medical standpoint. His comments are brief, however. "It is, and may be us'd outwardly, instead of Hungary water, in Aches, Pains, &c. especially that which is double distill'd."9 He says nothing about its inward values, other than dismissing the experiment which suggested it was better for the stomach than brandy. Sloane's view of the liquor itself is somewhat caustic:

Rum is made of Cane-juice not fit to make Sugar, being eaten with Worms in a bad Soil, or through any other fault; or of the Skummings of the Coppers in Crop time... and has an unsavoury Empyreumatical [decomposing vegetable] scent, which is endeavour’d to be taken off by Rectification, mixing Rosemary with it, or after double Distilling letting it stand under Ground in Jars.10

With that description in mind, it is difficult to imagine he thought much of it as an internal medicine.

1 John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, Vol. 2, 1708, p. 143; 2 Oldmixon, p. 152; 3 Hans Sloane, A voyage to the islands of Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 1, 1707, p. xxx; 4 Ligon, A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbadoes, 1673, p. 27; 5 Ligon, p. 51; 6 Ligon, p. 93; 7 Ligon, p. 27; 8 Ligon, p. 44; 9,10 Sloane, Vol. 1, p. xxx