Tobacco and Medicine Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Next>>

Tobacco and Medicine During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 14

Tobacco as Medicine - Using the Simple

Chasing a Swimmer, From Thrilling Narratives of Mutiny, Murder and Pyracy (19th c.)

"They [Nathaniel North's pirates, who were chasing a swimming man] would not shoot him, because it did not answer their ends; but at length North, who was in the boat, took the sprit, and struck him as he rose, and broke his jaw. They took him by these means, brought him on board, sent him to the surgeon, and when they despaired of his being able to speak, he asked for a pipe of tobacco, which he smoked, and drank a dram; after which he seemed very hearty." (Captain Johnson, The History of the Pirates, 1728, p. 388)

Medicines were divided into two basic categories during this period: simples and compounds. Simple medicines were those where nothing was combined with a plant while compounds involved mixing the plant other ingredients as well as altering it by chemical processes such as heating and distillation. (Chemically-processed medicines were sometimes separated into their own category, but for this article they are included with compound medicines.)

Chart of the Health Issue For Which Tobacco Suggested in the 15th -

Early 18th Centuries According to Grace Stewart

Simples could be used internally or externally. In the case of tobacco, there were several ways it could be administered internally. As explained in a 1722 book, "the Three common Ways of using it, to wit, by SMOAKING, CHEWING, or taking it in SNUF. The two first ways are design'd to promote a kind of Salivation, or an Evacuation of trouble some Rheum by Spitting. The Last is for the Discharge of Humidity by the Nose."1

English physician Robert James explained the basic uses of tobacco in his Pharmacopoeia Universalis. "The Leaves are the Part us'd in Medicine, which are said to absterge [cleanse or purge], incide [separate], and resolve [break up something medicinally]; to be somewhat astringent [draw together medicinally] and to resist Putrefaction. …The Juice also of Tobacco is much recommended to preserve the Teeth and Gums ....warm Leaves of Tabacco, or a Cloth dip’d in the Juice, are said to be very effectual."2

Some of the uses of medicinal uses of tobacco before the golden age of piracy were discussed in the section The History of Health and Tobacco. A complete list of ways tobacco was used between 1492 and 1724 as a medicine is identified by historian Grace Stewart as seen at right. While this gives a extensive range of ways tobacco might resolve health problems up until and through the golden age of piracy, this section focuses on how medical authors around the period of interest viewed tobacco, beginning in 1659 and up to a document promoting Cephalic Tobacco from 1722.

It is worth noting that many of these publications, including the pharmacopoeias which were written to explain the use of medicines, merely repeat information written by earlier authors. In the 1720 edition of Nicolas Culpeper's Pharmacopoeia, Culpeper says, "in reciting the virtues of this herb, I will follow [Carolus] Clusius [aka. Flemish physician and botanist Charles d' Ecluse], that none should think

Nicholas Culpeper (1655)

I do it without an Author"3. The reader may recall that Clusius' work was based on that of Nicholás Monardes, who first published his long list of tobacco uses in 1574 when tobacco was being built into a panacea. In addition to that, this edition was published almost 70 years after Culpeper's death, being based upon his 1652 book The English Physitian. However, Culpeper's book was still in wide use and so the information had currency during the golden age of piracy.

Culpeper identified a variety of different health problems that the tobacco simple was useful in treating. These included stubborn headaches, migraines, diseases with cold origins, asthma, a stiff neck, phlegm in the lungs, constipation, worms, kidney stones, rickets, joint aches, scabs, the itch (caused by scabies), carbuncles, new wounds, wounds made by poisoned weapons and ulcers.4 Culpeper specifically highlights tobacco's usefulness in treating worm, commenting "this I know by experience, even where all other medicines have failed"5. He continues, "Taken [smoked] in a Pipe it hath almost as many virtues; it easeth weariness, takes away the sense of hunger and thirst provokes to stool… it easeth the body of superfluous humours, opens stoppings: ...and indeed a man might fill a whole Volume with the virtues of it."6

In his 1707 Herbal, John Peachy explains that tobacco "resists Putrefaction [decomposition], provokes Sneezing; is Anodyne [relieves pain], Vulnerary [healing], and vomits."7 He says that applying the green leaves of tobacco to the body can cure leprosy, eliminate the itch and lice, heal wounds, cleanse ulcers

Artist: Adriaen van Ostade

An Apothecary Smoking a Pipe (1646)

and cure burns.8 Smoking tobacco can stop catarrhs [excessive mucus in the nose and throat], dispose a person to rest, eliminate weariness, strengthen the stomach, improve concoction of humors, and eliminate constipation.9 Chewing tobacco could result in weight loss when desired and help asthma.10

While he had mixed feelings about tobacco, physician Richard Carr said that it was 'serviceable' for toothaches, rheumy eyes and preventing asthma.11 He also suggested smoking tobacco to people who were were predisposed to having tumors in their throat. "I have found by Experience such to be removed thereby, upon leaving it off to return again, and again upon repeating it to disappear, by Virtue of its opening those little Drains which proceed from those Parts into the Mouth; for that Acrimony which is perceivable in the Smoak, solicits the Glands to a more considerable Discharge of their Contents"12.

The 1722 book given away to advertise a "Cephalick and Opthalmick TOBACCO ...prepared from the very best VIRGINIA Tobacco impregnated with the Quinteisence and Virtues of certain particular Herbs and Chymical Oils" mentions a lists of health problems for which a tobacco was useful. (For the purposes of this article, this tobacco is being considered a simple despite the fact that it is mixed with other herbs and oils. It could be reasonably argued that this is actually a compound medicine.) Among the various health problems it addressed the plague, poor vision, sore and watery eyes, hearing problems, headaches, toothaches, rheumatism, gout, dropsy, coughing, wheezing, difficulty breathing and trouble sleeping.13 It later adds that by smoking this tobacco, the patient's "Breast, Stomach and Lungs are eased where a troublesome Flegm"14.

From these various claims, it can be seen that tobacco was still being used for a variety of health problems not much different from the lists given in the late 16th century.

1 Of the Use of Tobacco, Coffee, Chocolate, Tea and Drams, 1722, p. 2; 2 Robert James, Pharmacopoeia Universalis, 1747, p. 379; 3,4,5 Nicholas Culpeper, Pharmacopœia Londinesis, 1720, p. 33; 6 Culpeper, p. 33-4; 7 John Pechey, The Compleat Herbal, 1707, p. 234; 8 Pechey, p. 235; 9 Pechey, p. 234-5; 10 Pechey, p. 235; 11 Richard Carr, Dr. Carr’s Medicinal Epistles Upon Several Occasions, Translated from Latin by John Quincy, 1714, p. 21; 12 Carr, p. 21-2; 13 Of the Use of Tobacco..., p. 6; 14 Of the Use of Tobacco..., p. 8

Tobacco as Medicine - Using the Simple: Smoke Enemas

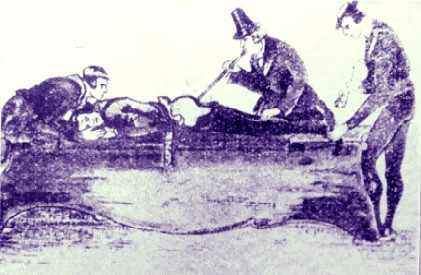

Administering a Tobacco Smoke Enema (18th century)

Tobacco enemas had wide support in the medical books from the time; several pharmacopoeias specifically mention their use. Physician John Pechey says, "The Fume of Tobacco blown up into the Bowels, is a most effectual Clyster in the Cholick [referring here to blockages in the intestines]."2 English physician Thomas Fuller gives a better description of the problem when explaining that modern medical authors "use the Smoak of Tobacco as a present Remedy in Flatulent Pains of the Guts, Convulsive Obstructions of the Belly, Colic, and Iliac Passion [complete blockage of the intestine]"2. The author writing the epistle to the English translation of Giles Everard's book on tobacco agreed, noting that "the very smoke of it is... singular in Clysters against the wind-Cholick"3.

Resuscitating a Drowning Victim Using a Tobacco Smoke Enema, From Avis au peuple

sur les

asphyxies ou morts, By J. J. Gardane, Plate II (1774)

This procedure endured well beyond the golden age of piracy. Writing in 1747, Robert James gives a detailed explanation of the use of the tobacco enema.

...the greatest Use of Tobacco in Medicine is in Clysters [enemas]; for the Smoak of Tobacco, convey’d into the Intestines, either by an Instrument contriv’d on Purpose, or blown in by means of a common Tobacco Pipe, will stimulate strongly, so as to procure Stools, when every other method of doing it has fail’d. Hence it is of Service in the Iliac Passions and some Species of Ruptures, attended with absolute Costiveness [constipation], and may be employ’d to very good Purposes in other Disorders where a strong and sudden Stimulus is requir’d.4

Several decades after the end of the golden age of piracy, tobacco enemas were noted to be administered to drowning victims in an effort to revive them. Unfortunately there is no evidence for this procedure being used before 1746. (For those interested, the use of tobacco enemas to revive drowning victims is explained in the article on Resuscitation of Drowning Victims at Sea.)

One of the few uses for tobacco mentioned by sea surgeons in their books from this period was in enemas. Sea surgeon John Moyle explains, "At Sea Men are oftentimes taken with fits of the Cholick, with insufferable griping [sharp pains]. ... Sometimes the Body is bound with this

Sea Surgeon John Woodall

Disease, and then in the West-Indies it is called the dry gripes. Sometimes there is a Looseness, with intolerable tortion [pain or torment] of the Bowels. If it were wind alone, an excellent Clyster were that of Tobacco, given in a fumigatory Clister-pipe"5. Fellow sea surgeon John Woodall discusses their use, mentioning several other problems tobacco enemas are useful in treating. He says that "the giving of it [tobacco] Glisterwise [via an enema] in a fume to a patient reversed in the Iliac passio, wherein it excelleth as also for many other obstructions, gripings, tortions, Iliacal, and other distempers of the bowels."6 Moyle goes on to state that these problems are caused "by corrupt humours, and windy vapours in the Tunicles of the intestines; it generally comes by cold."7

Woodall even designed a device he called the Enema Fumosum or Fumous Glister which could be used by his sea surgeon trainees to administer tobacco smoke enemas. A detailed explanation of this device complete with sketches is included in a special section in the second edition of his book the surgions mate. He explains that his syringe can work in two different ways. "[T]he one way [is] in the delivering into the body by inflation, any torrified or dry powdered medicaments in their powders, the other in delivering thereinto any vaporous medicaments as is said, and namely, the vapours [smoke] of Tobacco, of Nutmegs, Anni-seed, Colts-foot, Bay-berries, Mirrha, Aloes, or what else" can be made into a vapor.8

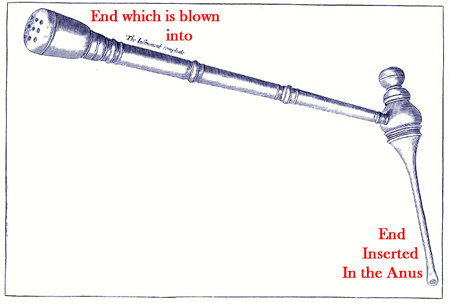

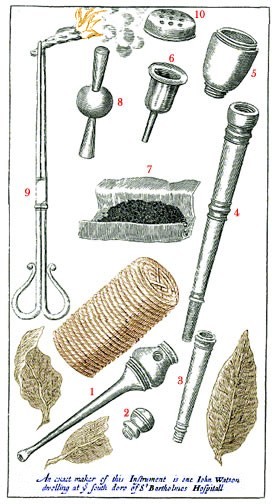

Woodall's Enema Fumosum Assembled, From the surgions mate (1639)

Woodall explained the procedure for giving a smoke enema for intestinal problems. First he recommends giving an ordinary liquid enema to empty the large intestine, "for so it [the tobacco smoke] may have the freer place by inflation, to force up the fume thereof, for the opening the obstructed parts, for the better effecting"9. Then a fine rag or thin bladder is wrapped around the head of the enema syringe (which has holes in it as seen in the diagram at right) which is then inserted in the anus 'as far as it will or can goe'. Next, it is pulled back a little (about 'halfe and inch') so that the rag or bladder does not block the holes at the end of the syringe. (This would be later excreted provided the tobacco enema did its job.) Once prepared, "by inflation or blowing it in with fitting continued force i[t] will efect thy desire."10

Thomas Sydenham With Clyster, From a Bronze Medallion

Writing almost thirty years after Woodall, English physician Thomas Sydenham provided a brief description of how this procedure was to be performed, although it provides nowhere near as much information as Woodall's. "I reckon the smoak of Tobacco, strongly blown up through a large Bladder into the Intestines by a Pipe inverted, to be the best, and most effectual Glister I know"11. Like Woodall, he suggests a tobacco enema only after the patient has first been given a normal, liquid enema to clear the anal canal and lower intestines as well as they can be.

Woodall provides a detailed diagram and a description of the parts which are to be assembled to make his Enema Fumosum. It may seem like there are an unusual number of pieces for this device, but it must be remembered that the space allotted to the surgeon on a ship was quite limited and larger medical tools would be more conveniently stored if they could be broken down into smaller pieces which could be conveniently stored in the surgeon's instrument chest or in their own separate box. Such compact devices were also less likely to be broken.

Of his Enema Fumosum, Woodall says it is "devidable parts in all are seven in number, viz."

The Components of Woodall's Enema Fumosum,

From the surgions mate (1639)

1. The first is the Glister pipe which ought to be in length ordinary, or according to art, a greater and a lesser as the present occasion may urge.

2. The second is the stopple to be screwed upon the head thereof, viz. of Glister pipe.

3. The third is the elbow piece screwed into the one side of the upper part of the glister pipe, standing Byas, or a scant, being framed so to stand, and that part ought to be in length two inches and a halfe, or neere three inches but not full three.

4. The fourth is the straight pipe of eight inches long in all; all consisting of foure particular parts, if devided or devidable; namely the long or fistula.

5. The fourth of the seven is a piece of Ivory screwed and fixed into the lower fistula or pipe, that containeth the silver or other metaline part thereof.

6. The next is the silver bole or cup within the said Ivory head, and conteneth the famous medicine, being to be accounted the sixth part.

7. And the seventh part is the cover screwed on the head thereof, being full of holes for the better inflation of smoake, all which rightly conjoined, maketh one entire instrument, which may justly bee named fistula fumosum.12

The artist mislabeled the seventh item; in his drawing, the actual item labeled 7 is a paper or pouch which contains powdered tobacco, while the cover Woodall describes as number 7 is labeled 10 in the sketch.

The artist for Woodall's book numbered several other things in the diagram, although Woodall only lists the first seven components by number in his text. Woodall discusses the other two numbered items without actually referring to the number shown in the diagrams. (These have been inserted here description for clarity.) Also used with the Enema Fumosum

19th Century Tobacco Smoke Enema Kit, London Science Museum (Wellcome)

are "a paire of fit forceps [9], holding fire[, along] with a Tobacco stopper [8], usuall to order it in [tamp the tobacco when] kindling"13. The artist also includes several tobacco leaves and a twist of tobacco not mentioned by Woodall in his description, each of which have been colorized in the diagram.

This type of device was in use long after Woodall. Naval historian John Keevil explains, "Woodall invented an apparatus for the injection of tobacco smoke to treat bowel obstruction, which naval surgeons still carried with them in the first half of the nineteenth century."14 A set of bellows was thoughtfully added to the resuscitation kit used by the navy at some point, probably in the late 18th or early 19th century, so that the ship's surgeons wasn't required to blow directly into their patient's anal canal.

1 John Pechey, The Compleat Herbal, 1707, p. 235; 2 Thomas Fuller, Pharmacopœia Extemporanea, 3rd ed., 1719. p. 234; 3 Giles Everard, “The Epistle”, Panacea, or the Universal Medicine, 1659, not paginated; 4 Robert James, Pharmacopoeia Universalis, 1747, p. 379; 5 John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, 1686, p. 109-10; 6 John Woodall, “Enema Fumosum”, the surgions mate, 1639, not paginated; 7 Moyle, p. 110; 8,9,10 John Woodall, “Enema Fumosum”, the surgions mate, 1639, not paginated; 11 Thomas Sydenham, The Whole Works of Dr. Thomas Sydenham, 3rd ed, 1701, p. 428; 11 John Woodall, “Enema Fumosum”, the surgions mate, 1639, not paginated; 14 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume I – 1200-1649, 1957, p. 217