Tobacco and Medicine Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Next>>

Tobacco and Medicine During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 6

Tobacco Use and Tools

The tools for using tobacco depended in part on the method of imbibing it.

Artist: Adriaen Brouwer - Smoker, Fumatore (mid 17th century)

Three methods of tobacco use were around during the golden age of piracy: smoking using either pipes or cigars, snuff and chew. Each of these originated with the American natives as we shall see.

Of the three, chewing tobacco has the least relevancy according to period sailor's books; there are no actual references to chewing tobacco in their books despite the fact that antiquarian Frederick William Fairholt says this method was "much in favor with sailors"1. Berthold Laufer also links sailors to chewing tobacco, although he does not mention English sailors. "The Spanish conquerors came into contact with the habit of chewing tobacco in the West Indies (account of Amerigo Vespucci) and Mexico (early accounts of B[ernardino]. de Sahagun and F[rancisco]. Hernandez)."2 The one exception is found in former sea surgeon Tobias Smollet's fictional account The Adventures of Roderick Random. There, Smollet explains that a sailor, after bringing a man wounded during an engagement took some tobacco "out his pouch, put a large chew of tobacco in his mouth, without speaking a word."3

Artist: Gerard ter Borch - Man Taking Snuff in a Tavern (1648)

Snuff is a little more relevant than chewing tobacco as far as seamen are concerned. We have already seen a few references of snuff being in the presence of sailors without any mention of its use, an indirect mention of a supercargo using it and one example of sailors using it from the accounts under study. Still, it was popular in parts of Europe during the golden age of piracy and some of the tools which were used by those using it were considered valuable plunder to privateers and pirates.

Smoking is the most consistently supported use of tobacco in the published period sea books. Although pipes and cigars were both in use during this period, only pipes appear in the English sea accounts. With this in mind, this section will focus on tobacco tools in use when smoking tobacco or using snuff. It begins with a look at the containers used to hold tobacco carots and twists which were used for both smoking and making snuff at this time. It then examines pipe smoking and the tools associated with that, followed by a look at cigar smoking. It finishes with a discussion of the use of snuff up through the golden age of piracy, how snuff was made and the implements used specifically to store snuff.

1 Frederick William Fairhholt, Tobacco Its History and Associations, 1862, p. 310; 2 Berthold Laufer, "The Introduction of Tobacco into Europe", Field Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology, Chicago, Leaflet Number 19, 1924, p. 42); 3 Tobias Smollet, The Adventures of Roderick Random, 1748, p. 204

Tobacco Use and Tools - Tobacco Containers

As discussed in the section on tobacco processing, it was purchased for smoking in either carots (also called carottes) or twists. The user cut tobacco off of these as required. Flaked tobacco was sometimes stored in a container, the earliest of which were boxes.

Antiquarian William Frederick Fairholt describes two boxes in his book which he says may have belonged to Sir Walter Raleigh. Of the first, he explains that it is

Raleigh's Alleged Tobacco Box, From Tobacco Its History and Associations, p. 226 (1862)

"of sufficient capacity to hold a pound of tobacco, which was placed in the centre, and surrounded by holes to receive pipes. It was thirteen inches high, and seven in diameter; formed of leather, and decorated with gilding."1 He includes a sketch of the other box which can be seen at right. Of this alleged second Raleigh tobacco box, Fairholt explains that it "has the initials W. R. conjoined within the lid. If not Raleigh's box, it is of his period, and is decorated with figures on one side in the costume of the end of the sixteenth, or beginning of the seventeenth century. On the opposite side is a hunting scene. The lid slides out; the head of the figure who supports the anchor forming a convenient projection to aid its course. The English rose is below; and at the bottom of the box a mariner's compass is engraved."2

Fairholt describes a number of other tobacco boxes in his text including a silver box valued at thirty shillings in an inventory from the late 17th century3, some made of tin and horn and oblong brass tobacco boxes which "contained all the smoker required, including materials for lighting the pipe, consisting of tinder, flint and steel, all packed in proper divisions."4

Dutch Brass Tobacco Box, MET Museum, late 17th century)

Fairholt says that sailor's tobacco boxes were "generally capacious, and made for the pipe as well, which was laid in one compartment of the interior. Such large brass boxes were generally carried by sailors, particularly Dutch ones, and were covered with rudely executed ornaments and inscriptions. Pictured semblances of their own good ships were common on the lids, and Dutch tobacco-boxes, or boxes in their style, were common to English sailors."5

Unfortunately Fairholt is somewhat vague on his dates. The one bit of hard evidence of a tobacco box in use by pirates come from the account of pressed man John Fillmore's time aboard pirate John Phillips ship Revenge. After Fillmore conspired with some other men to take Phillips' ship and sail it into Boston, he reported, "The honourable court which condemned the pirates gave me Captain Phillips' gun, silver hilted sword, silver shoe and knee buckles, a curious tobacco box, and two gold rings that the pirate Captain Phillips used to wear."6 It is unfortunate that he doesn't explain what was curious about the tobacco box.

Fairholt also points out that tobacco, "

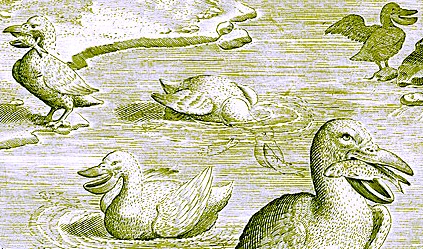

Engraving: Philip Gale and Karel van Mallery - Pelicans Fishing (1595)

if not placed in a metal box, is held in a pouch or bag; both being generally formed of leather."7 Several sea accounts mention using a pouch to hold tobacco, all of them referring to how pelican's beak pouch can be used to make them. Privateer Edward Cooke, captain of the Dutchess explains that pelicans have "a very large Craw serving to carry Provinder in, of which our Men make very good Tobacco-Pouches."8 Sea surgeon John Atkins explains that pelicans have "membranous Bags or Pouches, which stretch thence to the Extremities of their under Bills, capable, when separated [from the pelican], of holding a couple of Pounds of Tobacco"9. Buccaneer Lionel Wafer gives the most descriptive explanation of these tobacco pouches. "The Seamen kill them for the Sake of these Bags, to make Tobacco-pouches of them; for, when dry, they will hold a Pound of Tobacco; and by a Bullet hung in them, they are soon brought into Shape."10

1 Frederick William Fairhholt, Tobacco Its History and Associations, 1862, p. 225-6; 2 Fairhholt, p. 226; 3 Fairhholt, p. 227; 4 Fairhholt, p. 229; 5 Fairhholt, p. 227-8; 6 John Fillmore, “47. John Fillmore’s narrative”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 235; 7 Fairhholt, p. 225; 8 Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World in the Years 1708 to 1711, 1969, p. 120; 9 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 249; 10 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America, 1903, p. 123

Tobacco Use and Tools - Pipes and Pipe Paraphernalia

Among the English, pipe smoking was in fashion from the late 16th century all the way through the golden age of piracy.

Artist: att. Jacob de Monte - Charles de l'Écluse aka. Carolus Clusius (1585)

Writing in 1605, Charles de l'Écluse (known as Carolus Clusius in Latin) explained that the natives in Virginia employed "little tubes of which certain ones of clay in order to use of leaves of tobacco... The English consequently, brought back similar to the tubes" which were used by the courtiers to smoke tobacco.1 Historian David Harley is more specific, noting that mathematician Thomas Harriot brought pipe smoking to the English, based on a report given by court physician Théodore de Mayerne.2

However it arrived, pipe smoking took hold of the English population. Writing in 1598, German lawyer Paul Hentzner explained that the English "have pipes on purpose, made of clay, into the farther end of which they put the herb, so dry that it may be rubbed into powder, and putting fire to it, they draw the smoak into their mouths"3.

A couple authors writing after the golden age of piracy suggest that pipes in the early seventeenth century were dear. This idea appears to be derived primarily from a comment by John Aubrey who wrote a series of small biographies on noted men in England in the late 17th century. In his description of Walter Raleigh, Aubrey says, "I have heard my grandfather Lyte say that one pipe was handed from man to man round about the table. ...It [tobacco] was sold then for it’s wayte in silver."4 Referring to this, Berthold Laufer says, "This was done because the cost of a pipe was considerable."5 Antiquarian Frederick William Fairholt notes that Aubrey's memories agrees with what the dramatists of the age of Elizabeth and James I.6

Pipes could be made from a variety of materials. In his recollections about pipe smoking from grandfather Lyte, Aubrey says that early smokers "had first silver pipes; the ordinary sort made use of a walnutshell and a straw."7 Other types of metal were also used. Fairholt notes, "In the reign of William III [1689-1702], they were occasionally made of iron and brass."8 Similar to the walnut and straw pipe, buccaneer William Dampier reported that in Bahia, Brazil, that the nuts of what he calls the 'bastard coconut tree' were used to make "Boles of Tobacco-pipes". While this sounds like a rather large bowl,

Wooden English Pipe, c. 17th century, From Tobacco Its History and Associations, p. 160 (1862)

Dampier explains that these are "not a quarter so big as the right Coco-Nuts."9 Other types of wood were also used. Fairholt shows an image of "an old wooden tobacco-pipe, the spur of which projects considerably, and the bowl has been much burnt away in smoking."10 He suggests it is an 17th century English pipe based on the style.

However, as suggested by Clusius in 1605, the most common material for making tobacco

Photo: Kent County Council

Four GAoP Clay Pipes; 1&2 (1700-40), 3&4 (1690-1710)

pipes in England clay. The clay used to make English pipes during this time turned white when fired. This clay came from divers places such as in deposits along the the Rhine and Meuse rivers, Cologne, German, Utrecht, Netherlands, Liège, Belgium, Dorsetshire, England and Gouda, Holland.10 After firing, pipes were typically left unglazed.

Pipe-making was so important that King James I, despite his opposition to smoking, ordered that English pipes were only to be made by a group of Westminster pipe-makers recognized under Royal Charter. The group was reincorporated by Charles I in 1634 as the Tobacco-pipe Makers of London and Westminster and England and Wales. However, this company forfeited their charter in 1643 after failing to pay the annual rent due the King. A second company of pipe makers was given a Royal Charter of Incorporation in 1663 which continued through the golden age of piracy.11 The incorporation articles can actually be seen on the current web page of The Worshipful Company of Tobacco Pipe Makers and Tobacco Blenders website.

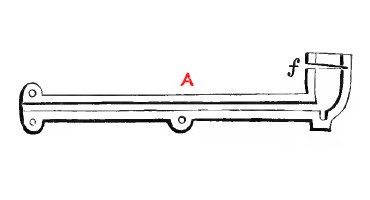

Fairholt provides a wonderful description of the method of pipe-making, including accompanying diagrams, which he quotes from of Chamber's Edinburgh Journal. (Paragraph breaks have been added for clarity.)

Pipe Making Mold, From Tobacco Its History and Associations, p. 177 (1862)

The first process is the breaking and pounding the clay with a wooden rammer, and mixing it with water to a consistency similar to that of putty. The clay, at the requisite consistency, then passes on to a man who pulls, twists, rolls, thumbs, and kneads it out... into small separate long-tailed lumps, each large enough, and to spare, for a single pipe. These he lays loosely together in a heap, ready for the moulder. The moulder... dexterously draws the long tail of the lump over a fine steel-rod which he holds in the left hand; performing in less than half a minute what seems a miracle of skill, by embedding the rod in the exact centre of the clay through the whole length of the pipe. He then lays the rod in the lower section of the mould, represented at A in our cut; the upper portion is precisely similar and is shut down upon it, and secured by a projecting pin in one mould fitting into cavities in the other.

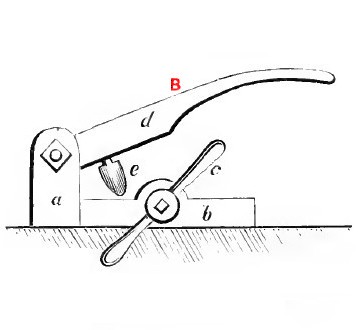

Pipe Making Press, From Tobacco Its History and Associations, p. 177 (1862)

It is then placed in the press B fixed to a bench by a strong beam a, with which is connected an iron plate b, having a screw turned by a handle c, which presses toward it another iron plate; between the two the mould is placed and squeezed tightly together, the handle d is then brought down upon it, the projecting rounded cone at e entering the mass of clay destined to form the bowl of the pipe; the clay is thus squeezed upward, and all that is superfluous is cut away by a knife, a passage for which is made in the mould at f; and when the mould is opened, the pipe is turned out complete as to form.

In this state, the pipes are passed to the trimmer, generally a young lad or a female. The trimmer, with a sharp steel instrument, first pares away the thin protuberances on the stem formed by the junction of the two sections of the mould; then dresses the bowl to a neat shape; then cuts the mouth piece smooth; then draws out the steel-rod and blows down the pipe, to be sure that it has a free passage for the smoke; and, lastly, lays it on the frame to dry, previous to burning in the kiln.

A pipe-kiln is more or less capacious, in proportion to the exigencies of the establishment; but an enormous number of pipes may be burned in a comparatively small kiln, as they are ingeniously packed on frames so that little space is lost, and are sufficiently fired in a short time. On inquiry, we are informed that the number of pipes made in an establishment when trade is prosperous and the demand brisk, is about forty-five gross a day; which gives an average of nearly five hundred pipes per diem for each of the hands employed.12

Although this description comes from the 19th century, the appearance of the pipes from earlier periods and the design of the machinery suggest that it would be fairly accurate for the golden age of piracy. It is probably the standardization of pipe-making and large-scale production of them through the formation of the guild by which "[t]he clay pipe soon became cheap and common."13 The large number of pipe fragments found in archeological

Photo: US National Park Service

Clay Pipe Fragments From Fort Vancouver, Washington

digs on sites from the golden age of piracy verifies that clay pipes were certainly not uncommon during the golden age of piracy.

Proof of the popularity of smoking among logwood cutters during this period comes from a study done in the 1990s by archaeologist Daniel Finamore and a team of researchers who excavated an eighteenth century logwood cutter camp site on the Belize River called Barcadares. Central American logwood cutters were often former sailors or pirates according to English merchant ship captain Nathaniel Uring, writing about his voyage taken in 1725 and 1726.14

From an analysis of the dig written by Heather Hatch we know that archeologists found a great deal of evidence supporting pipe smoking amongst the former sailors and pirates. Hatch explains that at the Barcadares site, "[p]ipe fragments are the most numerous artifacts... The pipe bowls fall generally into [archaeologist Daniel Finamore’s] expected occupational range of 1680-1730 and represent pipes of primarily Dutch manufacture."15 Hatch goes on to explain that tobacco pipes make up “the largest group of artifacts at the Barcadares at 36% of the total site assemblage."16

Hatch compares the Barcadares logwood cutter site with excavations of two 'civilized' colonies on Nevis from around the same period - Nevis Ridge and Port St. George. Her data shows that 35.32% of items found at Barcadares are pipes, while only 22.35% of items found at the Nevis Ridge Complex and 15.69% of the those found at the Nevesian Port St. George Site are pipes and pipe remnants. This means the density of pipes and pipe fragments among the sailors is almost 60% higher than at Nevis Ridge and 125% higher than at Port St. George.17 Even the larger number of pipes found at the Ridge Complex may have been caused by the presence of sailors. Hatch explains "that an exceptionally high proportion (65%) of the Port St. George pipe assemblage comes from the older Zone 3, which is potentially associated with the use of the site as a port, and likely indicates that sailors, slaves, or both account for most of the smokers from that site."18 It is no wonder that she states, "smoking was clearly an important social activity for the baymen."19

1 "Detecta ab Anglis duce Richardo Grenfeldo anno a Christi nativitate M.D.LXXXV. Wingandecaow (quam ipsi Virginiam nuncuparunt) novi orbis Provincia, triginta sex gradibus ab Aequatore Septenetrionem versus distantet contemperunt incolas frequenter uti tubulis quibusdam ex argilla factis, ad foliorum Tabaci magna abundantia apud eos nascentis, incensorum fumum hauriendum, sive verius sorbendum, valesudinis conservandae gratia. Angli inde reduces similes attulerunt tubos ad Tabaci fumum excipiendum; inde Tabaci usus per universam Angliam adeo invaluit, praesertim apud aulicos, ut multos similes tubos fiere curarint, ad Tabaci fumum sorbendum.”, Caraoli Clusius, Exoticorum Libri Decem, 1605, p. 310; 2 David Harley, “The Beginnings of the Tobacco Controversy,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Spring 1993, p. 30; 3 Paul Hentzner, Hentzner’s Travels in England During the Reign of Queen Elizabeth, Translated by Horace, Late Earl of Orford, 1797, p. 30; 4 John Aubrey, “Sir Walter Raleigh (1552-1618)”, Brief Lives, Vol. 2, 1898, p. 181; 5 Berthold Laufer, "The Introduction of Tobacco into Europe", Field Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology, Chicago, Leaflet Number 19, 1924, p. 35; 6 Frederick William Fairhholt, Tobacco Its History and Associations, 1862, p. 170; 7 Aubrey, p. 181; 8 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703 p. 64; 9 Fairhholt, p. 171; 10 See "White pipe clay", wikipedia.com, gathered 8/19/18 and Fairhholt, p. 176; 11 "History", The Worshipful Company of Tobacco Pipe Makers and Tobacco Blenders website, www.tobaccolivery.co.uk, gathered 8/19/18; 12 Fairhholt, p. 176-8; 13 Fairhholt, p. 170; 14 Nathaniel Uring, A history of the voyages and travels of Capt. Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 241; 15 Heather Hatch, “Material Culture and Maritime Identity: Identifying Maritime Subcultures Through Artifacts”, The Archaeology of Maritime Landscapes,2012, p. 223; 16 Hatch, p. 229; 17 Hatch, p. 226; 18 Hatch, p. 229; 19 Hatch, p. 231

GAoP Era Clay Pipe Design

While clay pipe designs followed a general template, the details of the pipes varied quite a bit

Artist: William Hogarth

Long-Stem Pipe, From Captain Lord George Graham in His Cabin (1745)

over time. The National Pipe Archive of England (NPAoE) website provides guidelines for dating pipes based on their design, which can help to understand what a pipe might have looked like during the golden age of piracy. For pipes during the seventeenth and early eighteenth century, they state that the pipes "had medium length straight stems (never curved) that were quite thick at the bowl junction. As a result, fragments usually show a clear taper along their length and can be quite chunky if the fragment comes from near the bowl. Stem bores were generally large at this period and so normally range from about 9/65" [sic] to 7/64", with a few pieces of 6/64""1.

With regard to pipe stem length, Berthold Laufer says that "Under the reign of William III (1689-1702) the Dutch style with larger bowls and long, straight stems was adopted."2 Antiquarian Frederick William Fairholt adds, "Pipe-makers seem to have discarded the long Dutch bowl by the middle of the eighteenth century, and to have recurred to the older form; but adapted it to the increased capacity of the smoker for quantity of tobacco."3

The NPAoE website says that the bowl style is most important to dating pipes

Basic Pipe Parts, Image from finds.uk.org, Kent County Council, (17th c. Pipe)

since this changed rapidly over time. At the same time, they note that bowls of pipes were subject to regional variations. "For this reason, it is important to look at specific local typologies as well as the more general national ones. "4 They go on to explain that in the seventeenth century, the bowl was a 'rather squat barrel-shaped' and always had milling around the rim. The state that the bowls usually tipped forward and their walls were pretty thick. "The bowl forms stayed quite similar but increased in size during the course of the century as tobacco became cheaper and more readily available and the quantity consumed at any one time increased. This is why the size of the bowl for is very important during this period and it is essential to compare the forms with a life size typology."5

Pipe Comparison, Somerset Pipe from Anna Smith, Somerset County Council,

Pembrokeshire Pipe from Sim Johnson, Portable Antiquities Scheme,

finds.uk.org

Fairholt explains,

The excessive cost of tobacco when originally imported to Europe, has been adduced as the true reason for this smallness of bowl. In the middle of the seventeenth century the capacity of the pipe increased with the increased duties on tobacco, and, until the era of Dutch William [late 17th century], kept on enlarging until it appears to have satisfied the most inveterate smoker6

The NPAoE similarly suggests that the cost of tobacco during the early period of adoption in England impacted the pipe bowl size.

However, the NPAoE also warns that the pipe bowl style was in transition between 1680 and 1720, dates which encompass most of the golden age of piracy. They explain that "bowl forms tended to become more elongated and forward leaning before adopting a more upright style, with the rims generally almost parallel to the stem... The bowl walls became correspondingly thinner and the use of rim milling stopped around 1700 in the south, but lingered on until around 1730 in the midlands and north"7. They suggest that a variety of regional variations were particularly prevalent during this time.

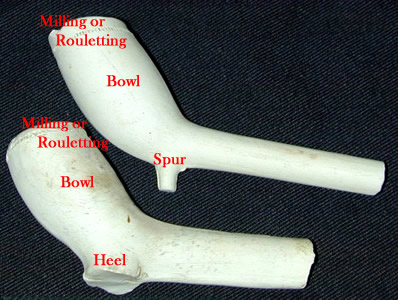

Clay Pipe Bowl and Spur/Heel Terms, Pipe Image from finds.uk.org, (16th or 17thc.)

The National Pipe Archive of England goes on to explain that there were basically two types of pipes in fashion at this time: those with a heel and those with a spur. "A heel is the term used for a flat-based projection underneath the bowl of a pipe, which typically has near vertical sides, or ones that flare out towards its base. A heel is usually broader than it is deep... A spur is the term used for a projection underneath the bowl that is usually longer than it is broad. It typically tapers to a pointed or rounded base"8.

Pipes manufactured for export were sometimes made without either a heel or spur. Heels were first made in the late 16th century, while spurs appeared in the early 17th century. Both seem to have existed in England. Here again, regional variations occurred in heel and spur styles between 1680 and 1720 and "some areas switched preference between heel and spur pipes (or vice versa) during this period."9 Their website provides links to nearly twenty documents, each specific to different location of pipe finds in England which can help guide those interested in correctly dating pipe styles.

Be Cautious When Using 'Simple' Clay Pipe Dating

Charts

to Try and Accurately Date Pipes

These general trends in pipe designs can allow experts to help date clay pipes and fragments of them which have been recovered in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. As a result of an incomplete understanding of everything involved in such dating, some websites and books have posted sketches of different kinds of pipe designs with dates attached to them which they suggest can be used to date pipes based on some of these design features. A quick search of the web and amateur books on the subject will turn up a number of such charts.10

However, these visual guides are often far too simplistic to be of any real value. The National Pipe Archive of England website clearly warns, "The skill and experience of the individual undertaking the work will play a large part in determining how accurate and reliable any assessment of dating is, and specialist advice should certainly be taken when dealing with large assemblages or those where the pipe dating is fundamental to the excavated deposits."11 This is particularly true for the golden age of piracy (defined here as 1690-1725) when clay pipe design was in flux and regional variations were many and varied. This is not to say that the visual guides are worthless, only that they ignore a number of important factors involved in trying to date pipes solely based on their profiles.

Before leaving the topic of pipes, it is worth mentioning a curious comment found in George Shelvocke's account of a privateering voyage taken around South America from 1719-1722. He explains that when they were sailing up the west coast of Mexico near Cabo Corrientes, their ship was "continually incommoded by numerous flocks of the birds so well known by the name of Boobies... However, for change of diet, some of my people made ragouts of them, and the smoakers made stems for their pipes of their long wing bones."12 It sounds as if they somehow used them to repair broken stems. It is a pity more detail is not given on how this was achieved.

1 "How to...date pipes", The National Pipe Archive website, www.pipearchive.co.uk, gathered 8/20/18; 2 Berthold Laufer, "The Introduction of Tobacco into Europe", Field Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology, Chicago, Leaflet Number 19, 1924, p. 36; 3 Frederick William Fairholt, Tobacco Its History and Associations, 1862, p. 175; 4,5 "How to...date pipes", gathered 8/21/18; 6 Frederick William Fairholt, Tobacco Its History and Associations, 1862, p. 161; 7,8,9 "How to...date pipes", gathered 8/21/18; 10 See for example, Ivor Noël Hume, Artifacts of Colonial America, 1985, p. 303, Alan Peat, "Dating clay pipe bowls: this is fun!", twitter.com, gathered 8/19/18 & Treasureguide@comcast, "6/23/15 Report - Ancient Gold Bracelets Found. Clay Pipes. Beach Sand & Movement. More New Finds Made On T. C.", treasurebeachesreport.blogspot.com, gathered 8/19/18; 11 "How to...date pipes",gathered 8/21/18; 12 George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 387