Tobacco and Medicine Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Next>>

Tobacco and Medicine During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 10

Non-Medical Perception of Tobacco in the GAoP

The non-medical perception of tobacco during the golden age of piracy seems to have been indifferent. As mentioned at the beginning of this article, it is not widely discussed in the period sea literature, being instead mentioned in passing,

Artist: Bernard Picart

Dutch Sailor on Deck Smoking (c. 1690-1730)

if at all. Yet a several sources cited previously show that tobacco was in wide use among the general public as well as being popular among sailors.

At the beginning of his journal, life-long sailor Edward Barlow explains how his sister and uncle were opposed to him becoming a sailor, "knowing how many ill husbands and drunken fellows used to go to sea, and that it was a place where many ill vices were in practice"1. While Barlow specifically mentions drinking and poor treatment of spouses here, tobacco use is conspicuously absent. When Charles Johnson recites the vices of pirate George Lowther's crew after they had retired to a small island, he explains that they "stay'd some Time to take their Diversions, which consisted in unheard of Debaucheries, with drinking, swearing and rioting, in which there seemed to be a kind of Emulation among them, resembling rather Devils than Men, striving who should out do one another in new invented Oaths and Execrations."2 Of course, a lack of popular opinion against tobacco in such sources is not proof in favor of it, but it is notable that tobacco was not typically mentioned as a vice in such lists of sailor's bad habits during this period.

Several accounts do mention what their authors disliked about tobacco use. There was also an acute awareness of the dangers of smoking on period sailing vessels; ships - being comprised of wood, canvas, rope and tar-and-rope calk - were particularly vulnerable to fire. This is verified by rules established before, during and shortly after the golden age of piracy. The need for such rules bears witness to the popularity of the habit among sailors. The negative public perceptions of the dangers of smoking are discussed in detail the following sections.

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 28; 2 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 312;

Non-Medical Perception of Tobacco in the GAoP - Harmful

A variety of authors mention problems with tobacco use, particularly regarding smokers. This social dislike of the habit really gained traction with the publication of A Counterblaste to Tobacco which was published by King James I of England in 1604. Several publications objecting to the use of tobacco followed this, many of which were intended to curry favor with James.1 However, the habit was

Frontispiece to Jakob Balde's "Die Trukene

Trukenheite" (Drunk Without Drinking) (1638)

clearly objectionable to some people regardless of the King's opinion. Complaints are registered in publications long after his death, including during the golden age of piracy.

One problem associated with smoking by authors was the gluttonous use of the herb. Physician John Hammond, writing under the pen-name of Philaretes in 1602, pointed out that tobacco "is without all method and order of most men received... at all times, at all houres, and of all persons… the smoake of Tabacco seemeth to the favorits thereof at no time unseasonable."2 The author writing the preface to the English translation of Edmund Gardiner's book was even more explicit and caustic, stating that "Tabacco is a fansticall attracter, and glutton-feeder of the appetite, rather taken of many for wantonesse, when they have nothing else to doe, than of any absolute or necessarie use, which is much to be discommended"3.

German priest and professor Jakob Balde gives a most scathing description of the perceived gluttony of tobacco users of the period in his 1638 book Die truckene Trunkenheit:

So soon as a ship with tobacco from overseas comes into port they [tobacco users] can scarce wait till the stinking cargo is unloaded-they take the first boat they can find, and off they go to the vessel. Then a box must be opened and a sample of tobacco cut off from the roll, that they may taste the nasty stuff, into which they stick their teeth as greedily as if it were the daintiest of morsels. If they find it to their liking, then they are all athirst to enjoy it, and quite beside themselves with happiness. After some gaping they begin to bargain and inquire the price; ducats or golden guineas, 'tis all one to them-they grudge no expense for an article like this: what is the good of money, they say, if it is to lie idle in the purse? Money, we know, is more precious than virtue, but unto them tobacco is dearer still.4

King James asks, "is it not both great vanitie and uncleanenesse, that at the table, a place of respect, of cleanlinesse,

King James I of England (c. 1600)

of modestie, men should not be ashamed, to sit tossing of Tobacco pipes, and puffing of the smoke of Tobacco one to another, making the filthy smoke and stinke thereof, to exhale athwart the dishes, and infect the aire, when very often, men that abhorre it are at their repast?"5 He goes on to say that the smoking "makes a kitchin also oftentimes in the inward parts of men, soiling and infecting them"6. Although he does not specifically mention the lungs, he adds that an "oily kinde of Soote... hath bene found in some great Tobacco takers, that after their death were opened."7

This notion of tobacco being a undesirable habit is echoed by sea surgeon John Woodall, who warned surgeon's mates and assistants not to become "given and dedicated to the pot [drinking too much alcohol] and Tobacco-pipe in such an unreasonable measure that they therby become in themselves base, despising vertue and commending vice."8

King James also alluded to the power of peer pressure in getting others to take up the habit. "[I]t is become in place of a [medical] cure, a point of good fellowship, and he that will refuse to take a pipe of Tobacco among his fellowes, (though by his own election he would rather feele the savour of a Sinke) is accounted peevish and no good company"9. He elsewhere suggests that "divers men very sound both in judgement, and complexion, have bene at last forced to take it also without desire, partly because they were ashamed to seeme singular... and partly, to be as one that was content to eate Garlicke (which hee did not love) that he might not be troubled with the smell of it, in the breath of his fellowes."10

It was also suggested that tobacco was harmful because of the difficulty experienced by someone first starting the habit. A book in 1722 explains that some writers felt tobacco had a

Artist: Adriaen van de Venne

Ardent Smokers, From Dutch Tobacco Shop (early 17th c.)

'Malignant Quality to be inseparable from the Plant' "which Common Tobacco manifestly abounds with, from whence proceed oftentimes many ill Symptoms from the Use of it, and which are particularly experienced when Persons First learn to Smoak."11 This was evident from symptoms "such as Sickness, Vomiting, Dizzyness in the Head, &c. as Learners to Smoak usually experience"12. Gardiner similarly points out says that people who have never used tobacco shouldn't be surprised "if it cause a vertiginie [dizziness] or giddinesse in the braine, epilepticall accessions, inclinations to fainting and founding, head-ach, dimnesse of sight, and other different effects, as I have often seene."13

Another harmful effect of tobacco - addiction - was mentioned by several authors. King James explains it simply: "To take a custome in any thing that cannot bee left againe, is most harmefull to the people of any land."14 Physician Hammond warns that "the venemous impression left in the stomacke by Tabacco, receiveth no ease by anything else whatsoever, but by Tabacco onely, eftsoone [soon afterward] reiterated and resumed. …Tabacco hath onely a certaine ease and paliation for a time by the fume of Tabacco received; but after perfect and absolute cure, this Tabacco by it selfe a thousand times resumed or reiterated, admitteth none."15 He elsewhere quotes the lament of one of his patients who is addicted to nicotine due to medical treatment with tobacco: "I would that I could so easely leave it [tobacco], condicionallie I had given 300 pounds more, for I finde my selfe hart sick that day, till I have tasted thereof."16

Several commentators from this period warn that tobacco is meant to be used as medicine, not for recreation. Physician John Hammond said in 1602 that medicines such as tobacco which purged humors shouldn't "by the rules of Phisicke

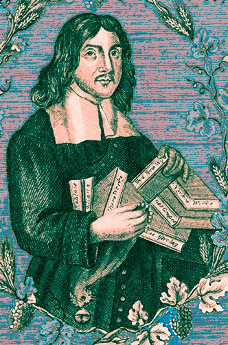

William Winstanley (1667)

[referring to medicines] ...bee familiarly and daily used of any man that hath respect either of his life, or regard to his health."17 However, Hammond backs off a bit on this idea, admitting that a "small quantitie Tabacco may be taken of any man without peril or imminent danger, & especially being corrected & purified by the force of the fire wherewith it is ministred. For that fire sometimes doth represte the poisoned vapour of venomous things"18. Two years later, King James noted that "as Medicine helpes nature being taken at times of necessitie, so being ever and continually used [when not necessary], it doth but weaken, wearie, and weare nature."19

In 1660 author William Winstanley declared, "Tobacco it self is by few taken now as medicinal, it is grown a goodfellow, and fallen from a Physician to a Complement."20 In 1714, apothecary John Quincy interpreted and published epistles written by Dr. Richard Carr to patients on various health topics which was first published in 1691. In one of these letters he addresses the topic of smoking tobacco, explaining that tobacco "may perhaps be of some Service to phlegmatick and cold Stomachs [referring to a person's humoral temperament and how it relates to the temperament of tobacco], but upon that Condition, that it be used only at those Times."21 Carr later says that a patient can receive "good Effects only where it [tobacco] has not been accustomed to before; if therefore you expect any Benefit from Tobacco, avoid by all Means using it too often. For nothing ought to be more taken Care about, than not to lessen in Time of Health, the Means of recovering it when lost."22

On the other hand, the physicians may have had another reason for suggesting that non-medical tobacco use was problematic. As modern author Grace Stewart points out, "part of the rebuttal to the physicians who contended that tobacco should be used only as medicine and only upon professional advice was that patients were successfully treating themselves and that, therefore, the physicians were losing business."23

1 Grace G Stewart, “A History of the Medicinal Use of Tobacco 1492-1860”, Medical History, July 1967, p. 240; 2 Philaretes (John Hammond), Work for Chimny Sweepers, 1602, not paginated; 3 Edmund Gardiner, Triall of Tobacco, 1610, folio 19r; 4 Jakob Balde, Die truckene Trunkenheit (Drunk without Drinking), 1638]”, cited in Count Eugenio Courti, A History of Smoking, Translated by Paul England, 1932, p. 119; 5,6,7 King James I of England, A Counterblaste to Tobacco, 1604, not paginated; 8 John Woodall, “The Office and Duty of the Surgions Mate”, the surgions mate, 1639, not paginated; 9,10 James I of England, not paginated; 11 Of the Use of Tobacco, Coffee, Chocolate, Tea and Drams, 1722, p. 5; 12 Of the Use of Tobacco...", p. 7; 13 Gardiner, folio 16v; 14 James I of England, not paginated; 15,16,17,18 Philaretes (John Hammond), not paginated; 19 James I of England, not paginated; 20 William Winstanley, England's worthies: select lives of the most eminent persons of the English nation, cited in Berthold Laufer, "The Introduction of Tobacco into Europe", Field Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology, Chicago, Leaflet Number 19, 1924, p. 35; 21 Richard Carr, Dr. Carr’s Medicinal Epistles Upon Several Occasions, Translated from Latin by John Quincy, 1714, p. 18; 22 Carr, p. 21; 23 Stewart, p. 240

Non-Medical Perception of Tobacco in the GAoP - Dangers of Smoking

In addition to the perceived possibility of harm being caused to users of tobacco from the plant itself,

Artist: Egbert van der Poel -

A fire in a village at night (1659)

another danger was presented by smokers: fires caused by careless lighting and smoking of tobacco. Count Eugenio Courti translates and quotes a 1643 German book which states that smoking tobacco was "highly dangerous to his habitation; owing to their clumsy method of lighting their pipes-with flint, touchwood, live coals, or tinder-it very often happened that while men were smoking in the flimsy wooden dwellings of that period a spark would settle on the timber, and the whole house, sometimes a whole village, would be in a blaze."1 Courti also states that "regulations were often issued at that time in innumerable towns of Europe, and with good reason, considering that timber was still in general use for building houses. In most towns and villages smoking in the streets was forbidden, and the watchmen were ordered to stop it."2 Unfortunately, he doesn't give an specific examples there so this is difficult to verify.

Courti does mention a 1634 Parisian Naval Order by "the Port Commander [of Paris] forbidding anyone de petuer [‘to smoke’] after sunset-no doubt on account of the danger of fire."3 Ships were particularly vulnerable to fire. Sailor Edward Barlow explained,

Burning of the Prince, From Thrilling Narratives of Mutiny, Murder and Piracy,

Hurst & Company (19th century)

Neither are ships and we poor seamen out of great danger of our lives in calms and fairest weather, for the least fire may set a ship on fire, many ships having been burnt by some careless man in smoking a pipe of tobacco; and in carelessless of the cook in not putting the fire well out at night; and of burning of a candle in a man’s cabin, he falling asleep and forgetting to put it out; and by burning of brandy and other strong liquors; and in many other ways a ship is set alight, and when they are on fire, it is a hundred to one if that you put it out, everything being so pitchy and tarry that the least fire setteth it all in a flame; and also there is great danger of the powder, for the least spark with a hammer or anything else in the room where it is, or the snuff of a candle causeth all to be turned into a blast, and in a moment no hopes of any person’s lives being saved, from death in the twinkling of an eye.4

Ironically, as previously noted, many sailors were enamored of the habit. This resulted in the establishment of formal

Artist: Gabriel Bray

Four Marines Eating Peas on Board HMS Pallas,

From the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London (Nov 1774)

rules about when and where smoking was permitted and the implementation of various safety procedures to protect the tinderbox environment of a vessel from fire.

Historian J. D. Davis explains that in the British navy, "Elaborate regulations were introduced to reduce the dangers [of fire on a ship]: the General Instructions of 1663 specified that no fires or candles were to be permitted below decks after the night watch was set, and smoking could take place only over a tub of water on the upper decks of forecastle. In 1680 the issue of leather buckets to ships in ordinary were ordered."5 Regulations were published in 1731 which specifically mention to danger of smoking. "Such as smoak Tobacco, are to take it in the Forecastle [the upper deck of a vessel in front of the the sailors' living quarters], and in no other Place, taking all possible Care to prevent Accidents from Fire."6 Smoking in the navy was prohibited below decks, a fact reiterated in the rules which applied to the Lieutenant. At night, he was to "visit the Ship between Decks, when he shall judge proper, and at other Times send down a careful Officer to see that there be no Disorder among the Men, nor any Fire or Candle burning any where, nor Tobacco smoaked between Decks."7

Photo: Mission

- Re-enactors Signing Articles

Such naval rules were sensible, so it should not be surprising that they made their way into some of the pirate articles written by the pirates. In order to join a pirate crew and get a share of any plunder they might take, recruits were often required to sign the ship's articles which were essentially the rules of the vessel. While some of the extant articles do not specifically address smoking, they do address the danger of fire. Edward Low's tenth article stated: "No Snaping of Guns in the Hould"8. 'Snaping' the gun caused it to spark, something which was sometimes done to light pipes as shown previously. Pirate Thomas Anstis' sixth article similarly said: "If any p[er]son or p[er]sons should be found to snap their arms or cleaning in the hold shall suffer Moses’ Law, that is forty lacking one."9 John Phillips' sixth article is much broader in prohibiting open fires below deck, specifically dealing with smoking. "That Man that shall snap his Arms, or smoak Tobacco in the Hold, without a cap to his Pipe, or carry a Candle lighted without a Lanthorn, shall suffer the same Punishment as in the former Article [thirty-nine lashes on the back]."10

As Barlow notes, one of the sources of danger on a ship when it came to open flame was the presence of gunpowder. While crossing the Isthmus of Panama in 1681, buccaneer

Artist: William Fadden

From Image Fur Traders in Canada (1777)

surgeon Lionel Wafer was badly burned due to the carelessness of a pipe smoker. The buccaneers had waded across a river and were sitting on the other side drying their possessions. Buccaneer William Dampier explains what happened next. "Our Chyrurgeon, Mr Wafer, came to a sad disaster here: being drying his Powder, a careless fellow passed by with his Pipe lighted, and set fire to his Powder, which blew up and scorch'd his Knee; and reduced him to that condition that he was not able to march"11. Because Wafer wasn't able to keep up with the buccaneers as they marched, he wound up spending several months with the Kuna natives in order to heal his wounds.

Captain Thomas Phillips commented on the natives carelessness around tobacco with their pipes while he was coasting along Africa in the merchant ship Hannibal in 1694. He explained

that when we have sold them two or three barrels of powder, and they have got it into their canoe, they have bought a case of spirits and fallen to drinking and smoaking tobacco till they were drunk, all the while sitting a top of the barrels of powder, and letting the sparks from their pipes fall upon them without any concern, which created a terror in us to see, and by which means they are frequently blown up; so that it is our custom, assoon as we have sold them any powder, to make them take it into their canoe, and put off, and lie about 200 yards from the ship till the rest of their business be completed, lest we might be injur’d12

With such examples, it is easy to see why it was necessary for sailors - naval and pirate alike - to create rules about when and how tobacco was to be smoked on a ship.

1 Warhaffte Beschreibung deß Edelen Krauts Nicotinae, von den Physicis Sana Sancta, von den Hispanis Tabaco, und von uns Teutschen Taback genennet, 1643, quoted in Count Eugenio Courti, A History of Smoking, Translated by Paul England, 1932, p. 119; 2 Courti, p. 196; 3 Courti, p. 150; 4 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 60-1; 5 J.D. Davies, Pepys's Navy: Ships, Men and Warfare 1649-89, 2008, p. 169-70; 6 Great Britain Privy Council, “The Lieutenant”, Regulations and Instructions Relating to His Majesty’s Service at Sea, 1731, p. 28; 7 Great Britain Privy Council, p. 91; 8 Ed Fox, 'Piratical Schemes and Contracts': Pirate Articles and Their Society, 1660-1730, University of Exeter, May 2013, p. 322; 9 Fox, p. 320; 10 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 342; 12 Thomas Phillips, 'A Journal of a Voyage Made in the Hannibal', A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol. VI, Awnsham Churchill. ed., p. 207