Tobacco and Medicine Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Next>>

Tobacco and Medicine During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 13

Tobacco as Medicine

“[Tobacco can be] taken for health, solace, ease, pleasure, profit, comfort, wantonnesse, good fellowship; being esteemed fit for all societies, as also received in for alement [nourishment], nutriment; yea, and for especially food in scarcity.” (Sea surgeon John Woodall, “Enema Fumosum”, the surgions mate, 1639, not paginated)

Photo: Wiki User Amanda44 - Nicotiana Rustica

Tobacco's perceived use as a medicine grew out of the idea that it could purge humors of the head, particularly those in the brain. This was linked to how explorers understood the natives in the Americas used it and the fact that tobacco use caused spitting and coughing, which was believed to be the body purging itself of one of the bodily humors, phlegm, primarily from the head.

A variety of uses in treating particular health problems and creating certain medicines using tobacco are found in books published during the golden age of piracy. Many illnesses were still said to be cured by the herb prior to this period. While some of these cures had been refuted, a large number still appeared in publications during this time. Of particular interest are tobacco's use as a smoke enema in curing intestinal blockages which was one of the few uses of tobacco recommended by sea surgeons. In addition, divers compound medicines included tobacco in their makeup as recorded in several pharmacopoeias from this period.

This section examines how tobacco was viewed in relation to humor theory up through the golden age of piracy, which health problems were said to be cured by tobacco focusing particularly on smoke enemas used in intestinal blockages and how tobacco was employed in compound medicines.

Tobacco as Medicine - Humor Theory

"The reason [that tobacco use is profitable] in Marriners may bee, because their bodies after long lying on the Seas, are filled and stuffed with badde and corrupt humours, on the which the force and power of Tabacco dooth worke, drawing and purging them forth of the body, no otherwise then other strong purges expell and purge forth such corrupt humours as have any similitude or likenesse to themselves." (Philaretes (John Hammond), Work for Chimny Sweepers, 1602, not paginated)

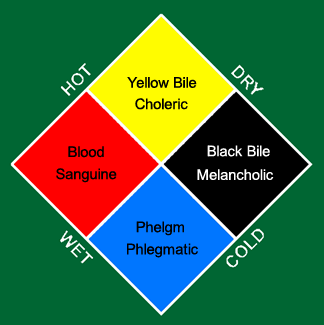

Humors "in a lax Sense may be taken for any Fluid: but Physicians restrain it chiefly to those of animal Bodies, and understand by it... all the Juices contained in Canals, or Vessels; and which are distinguished from one another by some manifest Qualities, as healthful, vitiated [spoiled], sanguine, cholerick and the like, according to their different Consistencies and Principles."1 In addition to animals, all plants were believed to have humoral properties. These were divided into four basic qualities: hot, cold, wet and dry. Plant humors were assigned a degree between one and four, with one being the smallest amount of that quality and four being the largest.

The Chart of Humors, Temperaments & Their Qualities

(For those interested, the humoral properties of plants are more fully explained here in the article on the Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory.) Like plants, illnesses were thought to have humoral qualities.

These qualities were used to determine which plants were optimal for the treatment of patients based on their health problems. A plant with the qualities opposite to that of the health problem was felt to be have the right qualities to remedy such illnesses. Like illnesses, people were believed to have dominant humoral qualities which were based on their humoral type or temperament. For a graphic representation of the four temperaments of people (choleric, sanguine, melancholic and phlegmatic) as well as the corresponding properties, see the chart at left. Plants with qualities opposite those found in a person's temperament were believed to be good for decreasing any excess humors a person might tend to have. So a medicinal plant with cold and dry qualities would be appropriate for use on a patient with a sanguine temperament which was contained an excess of hot and wet qualities.

There was some debate about the humoral qualities of the tobacco plant. Everyone seemed to agree that it was hot and dry, but opinions varied about its' degree of heat and dryness. Nicholás Monardes said the plant's "complexion is hot and drie in the second degree, it has vertue to heate and to dissolve"2. Physician Giles Everard cites a variety of writers on the properties of tobacco who give varying opinions including that it it is hot to one degree and dry to another. One of the authors he cites claims tobacco is not hot but extremely cold. However, most agree that it is hot and dry in either the second or third degree. Everard himself splits the difference, saying "that the green leaves are hot and dry in the second degree (which temperament the Sunne gives to them, as it doth to the root and stalk by its heat, and the Moon gives them their color) but when they are dried, they are hot and dry in the end of the third degree."3 Physician Nicolas Culpeper felt tobacco was hot and dry in the second degree.4

Physician Edmund Gardiner compares tobacco to opium, which he explains "consisteth of divers parts, some byting and hot, and others extreme cold, that is to say, stupefying and benumbing: if so bee that this bunumming qualitie, or facultie, doth not depend of an extreme cold temper, and that in the fourth degree, but proceedeth of the essence of the substance"5.

The debate over the tobacco's qualities had to do with the effects it produced when used.

Photo: Magnus Manske - Green NIcotiana Tabacum Leaves

Because some tobacco was said to have an intoxicating effect, it was thought to be cold. However, it was also bitter and purged those who used it through coughing, spitting and even vomiting, which suggested it had hot and dry properties. Gardiner points out that "the greene leaves layed upon ulcers, draw out filth and corrupt matter, which a cold simple would never doe."6

The degree of a plant's properties affected its use and popularity. Second degree purges were generally considered gentler than third degree purges, so they were preferred by physicians unless they failed to provide the desired effect. "Rougher" third degree purges were used when second degree purges failed, although they were not considered to be as desirable because of the impact on the patient.

John Hammond (writing as Philaretes) felt that it was bad for anyone to use tobacco, regardless of their temperament. "For it doth not onely consume and dissipate natural heat in them (by increasing of the unnaturall) but it waíteth also & drieth up radicall moisture (the principall subject of native heat) so that heereof insueth in the bodie great store of crud & undigested humours, the effects of immoderate heat in us."7 From this, Hammond (clearly no fan of tobacco) says that he believes tobacco is 'very dangerous' for all "constitutions whatsoever, to bee overbold with Tabacco."8 Most physicians during this time didn't share his strict view, however.

Yet most physicians thought tobaccos had use for particular temperaments. Edmund Gardiner explained that tobacco "must of necessity be verie good

, Physiognomische Fragmente, Johann Kaspar Lavater, 1775-8m.jpg)

The Four Temperaments (Body Types), From Physiognomische

Fragmente, By

Johann Kaspar Lavater (1778)

and holesome for those men that are of moist constitutions"9 (sanguine and phlegmatic). He goes on to describe such people as having soft bodies, pale-skinned, 'thick withal', with dull senses, "slothfull and lumpish... by reason their naturall heat is languishing and feeble, and drowned with moist and cold humors... loving their ease and idlenesse, whereby many crude and raw humors are heaped up in their bodies, it must needs bee graunted that Tabacco being hot and drie in qualities, must of necessitie do them much good"10. He elsewhere explains, "Tabacco is very holesome for colde complexions... considering that in this state of bodie there lacketh heat sufficient, and the other powers and faculties natural, are not able for the weaknes of the instruments and organs, to attract and digest that nourishment that is moist"11. He elsewhere explains that those with cold complexions can benefit from tobacco. While moist temperaments are found in both phlegmatic and melancholic temperaments, Gardiner focuses on the phlegmatics. He said that such people are "repleat with much fleagme, and flegmatick excrements, which maketh them lumpish and sleepie, forgetfull, slow of bodie and minde, and pale coloured, except sometimes at the coming of their especiall friendes they bee heated with wine or good Tabacco, and thereby have dumps driven out of their minds"12. He says

Tabacco consequently doth much good unto all such, whose heads are filled with moistish vapours: for those fumes or reekes, striking upwards as in a stillatorie [distillery], grow into a thicke, and snivelly fleagme, whereby through coldnesse of the braine, the parties become subject and open to sundry diseases, as poze [catarrhs], murre [nose and throat infections cause by rheum] ,hoarseness, cough & many others; of which sort is rheume or destillation of humours from the head13

An book published in 1722 intended to promote a particular type of 'healthful' tobacco explained that "When Persons are of a Moist, and Phlegmatick Constitution, and Habit of Body, a moderate Discharge of this Saliva is found to be of Service, and for this End it is that This most excellent Tobacco is SMOAKED."14 They further explain that their 'cephalick' tobacco will "promote chiefly a Discharge of superfluous Rheum and Humors by the way of Spitting, to be of Benefit thereby to Moist and Phlegmatick Constitutions."15

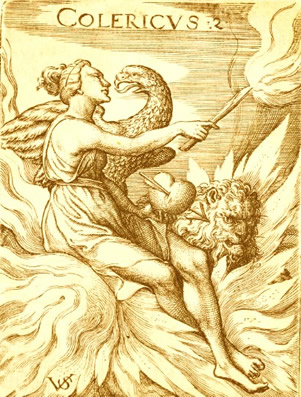

Artist: Virgil Solis

Choleric or Phlegmatic Temperament (c. 1530-62)

Of course, if a hot and dry plant works well for those with cold and wet temperaments, the opposite must also hold true; those with hot and dry temperaments will have trouble with it. Everard says that tobacco is particularly bad for "those that are cholerick [having hot and dry qualities], whose brains cannot endure excess of heat, for the[ir] native heat would be oppressed by the accidental heat."16 Gardiner comments that people whose appearance or temperament is of a dry quality will find "that tabacco being a hot plant, is very hurtful to them, & in no wise to be used; for this is not the way to subdue and alter, but rather make one more cholericke and hot"17 and "must in any wise banish Tobacco farre from them, as a thing most pernicious."18 Hammond warns that cholerics who "often use the feume of Tabacco, no doubt they should increase much their distemper, for like [qualities] added to his like" and "in natural reason and common sence it seemeth true that the extreame & violent dri'th & heat of Tabacco, maketh it far unfit & unwholsome for thin & cholericke bodies"19. Physician Richard Carr similarly explains that people who are hot and dry (whom he says are of a bilious or saline constitution) who are generally thirsty, lean, hot and have thin and yellow urine, "unless you would [want to] aggravate them, forbid the Use of Smoaking."20

Hammond also discusses problems with tobacco use of people of a melancholy temperament, because use of the plant "is a great encreaser of melancholy [black bile] in us, and thereby disposeth our bodies to all melancholy impressions and effects proceeding of that humor."21 He provides a very detailed explanation of why this is so which basically says that since tobacco purges phlegm - a 'thin' humor - using tobacco means there is less of it is available for making up the bloud resulting in the blood being composed of the thicker 'dregs' or melancholy humors. As a result, "the melancholy person by reason of the superfluous earthly and drie matter mixed with his bloud, hath his complexion more wan and swarte [black], his conceit of braine more dull and hard, his minde given to sollitarinesse and private life."22 Based on this, Hammond warns, "Tabacco therefore ought in no respect to be familiarly used of the melancholy person"23. He is, however, the only physician under study to suggest this.

Humor theory also looked at people and their environment in a way which suggested various interactions. In addition to plants' qualities making it appropriate and inappropriate for different temperaments, it also affected how well it worked for people based on the season, their age and location.

Artist: Karel Dujardin (att)

Portrait of a Young Man Smoking (17th century)

Several physicians said that youth were more likely to have trouble with tobacco. Giles Everard warned that "young men especially must take great care how they suck in this smoke, for the custome and too much use of it, brings their brains out of order, and makes them to be hot, so that they lose their good temper, and are beyond the bounds of their health, and that sacred anchor is lost irrecoverably."24 Hammond, never one to miss a chance to reduce tobacco's use, explains "this naturall heat in youth, by the immoderate use of this fierie fume would soone turne unto a heat unnaturall, and thereby be occasion of infinite maladies."25 He expands upon these maladies, noting that 'divers yong Gentlemen' in his experience have suffered fluxes and dysentery as well as pointing to a scholar at Bath "was supposed to have perished by this practise, for his humours beeing sharpened and made thin by the frequent use of Tabacco... they ran in such violence, as that by no Art or Phisicks [medicine] skill they could be stayed, till the man most miserably ended his life, being then in the verie prime and vigour of his age."26

Hammond also says that older people are likely to have problems using tobacco because they are 'naturally dry' as can be seen by "their skin parched, their faces withered, their sinews stiffe"27. From this he draws the conclusion that the elderly body, being 'naturally dry and hard' has trouble converting moist humors such as phlegm so any external agent which unnaturally draws such humors away from them contributes to health problems. Here again, no one draws this conclusion.

The place where a plant came from was also of interest to humorists. Plants from the place where you were born were believed to be more useful and more powerful than those from other places. This is reflected in Hammond's explanation of why tobacco doesn't seem to harm American natives. He says that the natives have differences in the makeup of their "bodies and humours from ours, [which] may alter much the case. Or else, that long custome and familiar use of this Tabacco from their infancie, hath confirmed their bodies to suffer & endure the same without hurt or offence: for custome altereth nature."28

Photo: Magnus Manske

Nicotiana Tabacum in the Cambridge University

Botanic Garden

He elsewhere suggests that "a secret vertue and specificall qualitie [may have been] given the Indians by nature, whereby they are not overcome by this kinde of poyson, as other Nations be."29

Edmund Gardiner, not entirely opposed to tobacco, suggests something different, although it reflects the same idea. Since tobacco is "now planted in the gardens of Europe, it prospereth very well, and cometh from seed in one yere to beare both floures & seed. The which I take to be the better for the co[n]stitution of our bodies, then that which is brought from India, and that growing in the [West] Indies, [since tobacco grown in people's country of origin is] better for the people of the same countrey"30.

Gardiner is one of the only physicians under study to discuss which seasons are most appropriate for tobacco use. Although he advises against excessive tobacco use, he says spring is the 'safest' time. In winter, most of the illnesses seen - pluresy, inflammation of the lungs, lethargy, stuffy head, pain in the breast, sides and loins, among others - are of a type where "Tabacco is a noble medicine, and fit to be used."31 On the other hand, Gardiner feels in summer, the time of fevers, bleary eyes, vomiting of choler, fluxes and similar maladies, tobacco cannot 'bee verie holesome'32. And, "in this season which we call the fall of the leafe, we must not too often use Tabacca, unles with great warinesse & advise of the learned"33. Henry Butte, although not a physician, similarly suggest that winter and spring are the proper seasons for using tobacco by in his wry 1599 cookbook.34

1 John Quincy, Lexicon Physico-Medicum, 1726, p. 212; 2 Nicholás Monardes , Of the Tabaco and of His Greate Vertues, 1577, f.34v; 3 Giles Everard, Panacea, or the Universal Medicine, 1659, p. 14; 4 Nicolas Culpeper, A Pharmacopoeia Londiis, 1720, p. 33; 5 Edmund Gardiner, Triall of Tobacco, 1610, p. f.10r; 6 Gardiner, p. f.9v; 7,8 Philaretes (John Hammond), Work for Chimny Sweepers, 1602, not paginated; 9, 10 Gardiner, p. f.13v; 11,12 Gardiner, p. f.15v; 13 Gardiner, p. f.15r; 14,15 Of the Use of Tobacco, Coffee, Chocolate, Tea and Drams, 1722, p. 8; 16 Everard, p. 46; 17 Gardiner,p. f.14v; 18 Gardiner,p. f.13r; 19 Philaretes (John Hammond), not paginated; 20 Richard Carr, Dr. Carr’s Medicinal Epistles Upon Several Occasions, Translated from Latin by John Quincy, 1714, p. 16; 21,22,23 Philaretes (John Hammond), not paginated; 24 Everard, p. 45; 25,26,27,28,29 Philaretes (John Hammond), not paginated; 30 Gardiner,p. f.9r; 31 Gardiner,p. f.12v; 32 Gardiner,p. f.11r; 33 Gardiner,p. f.12v; 34 Henry Buttes, Dyets Dry Dinner, 1599, not paginated

Tobacco as a Purge

"In addition, dinner is finished with half a dozen pipes, and a pot of tobacco on the table for smoking, which is a general thing for both women and men, who believe that without tobacco one could not live in England, because they say that it dissipates the bad humors of the brain." (Albert Jouvin de Rochefort, Le Voyageur d’Europe, Tome III, 1672, p. 467)

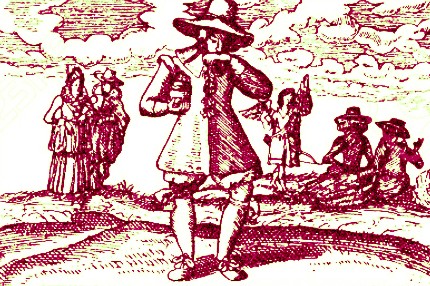

Using Tobacco as a Purge, From Crafft, Lugent und wurctung des

hochnutzbarlichen Tabac durchs A.B.C. gezogen fein groblich,

Tobacco

Broadsheet (early 17th century)

Tobacco's ability to purge humors was one of the most discussed features of the plant by physicians in the 17th century. According to humor theory, physicians sometimes needed to remove unwanted humors from the bodies of their patients to keep them 'balanced' and thus healthy. A variety of procedures were employed for this purpose including bloodletting, creating fontanels and purging the body of humors.

Purging can be further subdivided into using medicines which encouraged people to sweat (diaphoretics or sudorifics), urinate (diuretics), defecate (laxatives), vomit (emetics), salivate/spit and sneeze (sternutories). Tobacco was considered a purge because it caused salivation, vomiting and sneezing. This was thought to give it the ability to purge unwanted humors in the head and stomach. Physician James Robert said that tobacco leaves were "a strong Sternatatory, and Apophlegmatism [purger of phlegm]; and is narcotic, vulnerary [healing], and emetic."1

Tobacco was recommended by Gardiner for use in purging phlegm. He explained, "Fleagme in a mans bodie, as it is divers; so diversely it must be altered; for being by nature cold and moist, it easily is converted into thicknesse, or hard & tough sliminess, and in regard of his tenacious qualitie, it is verie difficult to be removed"2. He said that most medicines couldn't attract phlegm so they couldn't remove them. Instead, phlegmatic humors needed to be softened. Gardiner said that the way "to cause [phlegm] to be pliable and yeelding, there be five things required; namely, heat, siccitie [dryness], attenuation, abstersion, and cutting or dividing, which we call incision: all which properties Tabacco is furnished withal, and adjudged fit to be used in all tough and viscous humours wherewith the bodie is over-charged."3

Using Tobacco Snuff as a Sternutory, From Crafft, Lugent und wurctung des

hochnutzbarlichen Tabac durchs A.B.C. gezogen fein groblich,

Tobacco

Broadsheet (early 17th century)

Humors of the head gave concern to some seventeenth century medical men. Gardiner noted that he was "driven into an admiration, to consider how such abundance of filthy humors should rest in the head, which Nature one while at the mouth, another while at the nose and throat, expelleth and purgeth."4 He recommended the use of snuff to help this process. "Sternutories, especially those which are made of Tobacco, being drawne up into the nostrels, cause sneesing, consuming and spending away grosse and slimie humors from the ventricles of the braine."5 However, Gardiner also warns that sternatory medicines "are not so fitting, where the braine or head, the breast or lungs, [which] doe abound with verie crude or raw humours and superfluities; by reason that they doe move, trouble, and shake those parts too much, and too vehemently, which ought rather to be moderately comforted, warmed, and suffred to bee let alone quietly"6. If left to themselves, he says such humors will be digested or concocted and 'settled'. Once this is done, "then sneesing medicines are taken with good successe, and doe prevaile very much."7

The author writing the preface to Giles Everard's Panacea in 1659 recommended the syrup of tobacco (a purge made with licorice and honey), "for this will wonderfully stay Defluxions of Rheum [watery discharge from the nose and eyes]. The leaves chewed or bruised in the palate, do the same."8 He goes on to explain that this melts congested phlegm in the head and dries up the rheum there. "I know not whether there can be a more happy or more certain Remedy found out for this purpose."9 He goes on to explain that tobacco "smoke is excellent taken by the Nostrils, for it is properly belonging to the brain, and it is easily conveyed into the cels of it, and it cleanseth that from all filth (for the brain is the Metropolis of flegme [phlegm]...) it must be taken three hours before meat [food], for so it doth more conveniently discuss and cleanse the peccant [offending] humours."10

Melancholic Temperament, From Deutsche Kalendar (1498)

Physician John Hammond, aka. Philaretes, was opposed to the purging ability of tobacco. He warns that it can cause "immoderate purging and evacuation, by meanes whereof, great part of that liquid and moyst matter is purged out of the body that retaine and keepe it in perfect state and temper."10 As previously explained, Hammond believed it would purge the humors needed to engender the thin parts of the blood, which left the thicker melancholy humors behind causing health problems. He elsewhere explains that while the purpose of purges was to remove unwanted humors, when a healthy person used tobacco, the purging function "either loseth [its] operation and action, & therby is converted into some bad humour in the bodie, or else it draweth and expelleth foorth humours very profitable & necessary for the nurrishment and sustentation of the body."11 As a result, he warned that "all purges must needs bee to found and healthy bodyes very perillous and dangerous."12

Although not a physician, King James I weighed in on the notion of tobacco being a humoral purge - with a predictably negative view. He began by explaining the promoter's idea "That the braines of all men, beeing naturally colde and wet, all dry and hote things should be good for them; of which nature this stinking suffumigation is, and therefore of good use to them."14 He retorts that this idea "is an inept consequence: For man beeing compounded of the foure Complexions, (whose fathers are the foure Elements) ...yet must the divers parts of our Microcosme or little world within our selves, be diversly more inclined, some to one, some to another complexion, according to the diversitie of their uses"15. As interesting as this explanation is, it actually does not address the central idea that hot and dry medicines were good for cold and wet body parts.

1 Robert James, Pharmacopoeia universalis, 1747, p. 379; 2 Edmund Gardiner, Triall of Tobacco, 1610, f.17v-18r; 3 Gardiner, f.18r; 4 Gardiner, f.25v; 5 Gardiner, f.25v; 6,7 Gardiner, f.25r; 8,9 Giles Everard, Panacea, or the Universal Medicine, 1659, p. 42; 10 Everard, p. 42-3; 11,12,13 Philaretes (John Hammond), Work for Chimny Sweepers, 1602, not paginated; 14,15 King James 1 of England, A Counterblaste to Tobacco, 1604, not paginated