Tobacco and Medicine Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Next>>

Tobacco and Medicine During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 11

The History of Tobacco and Health

One of the reasons tobacco was brought to Europe was that it was thought to have medicinal properties. Nearly all of the historical references to tobacco in the late 16th century mention its use as a medicine by the natives. This made it particularly interesting to European physicians and

Amputee Smoking, From Tobacco

Advertisement Card (18th Century)

apothecaries. Most health professionals during this period believed that every plant had some medicinal use; those which didn't solve health problems simply had an as-yet undiscovered power. Foreign-grown plants such as tobacco provided new opportunities for healing resulting in many European physicians embracing foreign plant importation.

During the late 16th and early 17th century tobacco became known for its supposed ability to cure many different health problems based on publications gathered from reports of its use. This reputation increased over time, resulting in the herb being declared a panacea, or cure-all for health problems. (The placebo effect likely played a role here.) Such a reputation couldn't last, of course. Beginning in the early 17th century, tobacco's magical healing ability began to be questioned. By the mid-17th century, its reputation as a panacea had been tarnished. Yet pharmacopoeias continued to credit it with healing abilities. Attempts were even made to create strains of 'healthful' tobacco which benefitted from tobacco's earlier reputation as a universal remedy well into the 18th century.1

Grace Stewart imposes an interesting structure on the history of the use of tobacco in a medical capacity. She does this by looking at the books which addressed the medicinal uses for and against tobacco throughout its history. Her study includes 175 books2 published between 1503 and 1665, divided into five periods. These five periods are: 1492-1536 (Early History) 1537-1570 (Coming to Europe), 1570-1585 (Establishing Panacea Doctrine), 1586-1600 (Completing Panacea Doctrine), 1601-1700 (Debating Panacea Doctrine). Note that most of the names assigned to these periods are based loosely on Stewart’s text; she does not assign names to all of them.

The first two periods focus on the medicinal use of tobacco in the new world. Stewart identifies eighteen relevant

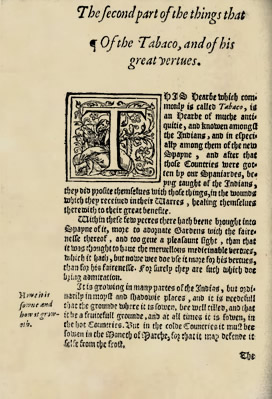

The First Page of Nicolas Monardes' Section on

Tobacco, From Joyfull Newes out of the newfound

world,

John Frampton, ed. (1580)

documents written between 1492 and 1536 (Early History).3 These come from accounts written by explorers, sailors, historians, missionaries and others who had visited the new world. Although some of these documents were not published during this period, they were written by people using original observations which were made during that time. Stewart's second period - 1537 to 1559 (Coming to Europe) - includes fourteen books published in Europe and Mexico. Similar to those in the first period, these books were written by explorers, historians, missionaries, botanists and physicians. "When not written by direct observers, the books repeated (not always accurately nor without embellishment) what the eyewitnesses had told of the various medicinal uses of tobacco from 1492 to 1536 in the Americas."4

The establishment of tobacco as a panacea, or "universal Medicine, or a Remedy for all Diseases"5, took place in the next two periods identified in Stewart's research. The idea that tobacco was a panacea was created in the third period, 1570-1585 (Establishing Panacea Doctrine) with the identification of the wide variety of health problems that tobacco was purported to cure. During this time Stewart says that the "doctrine and practices were elaborated, assembled, and firmly established. In this fifteen-year span, forty-five books mentioning the new treatment were published"6. These included herbals and pharmacopoeias, histories, dictionaries, horticultural and medical books. She notes that the idea of tobacco as a panacea was 'finished' by literature published in the fourth period: (Completing Panacea Doctrine). She identifies thirty-eight books written during this time, including several materia medicas ('medical materials' books) and pharmacopoeias as well as popular literature. These were written by botanists, historians and poets, among others. "In these fifteen years, physicians invented new formulae using tobacco, and they found new end uses for the plant"7.

Although tobacco had reached the pinnacle of popularity as a medicinal by the end of the 16th century, many of the health problems identified as curable by

A Disagreement Turns Sour, From Ned Ward's Vulgus Brittanicus (1710)

tobacco up to this point were not. This was recognized during fifth period [1601-1700 (Debating Panacea Doctrine), where the effectiveness of tobacco as a medicine was questioned. In the first years of the 17th century a book was written opposing the use of tobacco for health, which was rebutted by three following books "and thus the stage was set for the London tobacco controversy that continued for about sixty-five years."8 Before the controversy was over, twenty-six books debating the effectiveness of tobacco as a medicinal had been published in London alone. (Stewart says that similar books were published elsewhere in Europe although she admits that they are fewer in number and she does not include them in her analysis.) "Eight of the physician-writers were proponents, three were opponents, and two others could see both harm and good in the medicine. Other writers, not physicians, who took part in the paper war on tobacco medicine included the King of England, a Welsh judge, and poets."9

The following sections discuss the history of tobacco as a medicine and a panacea, breaking it into three periods that combine those included in Stewart's research: 1492-1570 (The Beginnings of Tobacco as Medicine), 1570-1600 (Tobacco as a Panacea) and 1601-1725 (Debating Tobacco's Effectiveness as a Medicine). The last category has been expanded because the debate continued well past the period identified by Stewart. These sections will look at the medicinal aspects of tobacco, focusing primarily on those books which have been discussed previously in this article.

1 For example, see Of the Use of Tobacco, Coffee, Chocolate, Tea and Drams, London, 1722; 2 Grace G Stewart, “A History of the Medicinal Use of Tobacco 1492-1860”, Medical History, July 1967, p. pp. 250-3 & 263; 3 Stewart, pp. 231-3 & 250; 4 Stewart, pp. 233; 5 Ephraim Chambers, "Panacea", Cyclopedia, Vol. 2, 1728, p. 736; 6 Stewart, pp. 235; 7 Stewart, pp. 237; 8,9 Stewart, pp. 239

The History of Tobacco and Health - The Beginnings of Tobacco as a Medicine (1492-1570)

The first references to tobacco and health come from Columbus' voyages. Bishop Bartolome de las Casas' interpretation of Columbus' journal suggests both a medical benefit and detriment to the natives who smoked the plant. "Having lighted one end of it [a cigar], they suck at the other end or draw in with the breath that smoke with which they make themselves drowsy and as if drunk, and in that way, they say, cease to feel fatigue."1

Artist: Theodore de Bry/ Jacques Le Moyne

Natives Using Tobacco for Healing, "Aegros Curandi Ratio" (Patient System),

From Grand Voyages, (1591)

Sailor Ramon Pane suggests a stronger link between tobacco use among the Taino natives and health in his account of Columbus' second voyage, albeit a rather mystical one. He explains that a sick native's physician "must needs purge himself like the sick man and to purge himself he takes a certain powder called cohoba [tobacco] snuffing it up his nose which intoxicates them so that they do not know what they do and in this condition they speak many things incoherently in which they say they are talking with the cemis [deities] and that by them they are informed how the sickness came upon him."2 Here again there are examples of a benefit - determining the sick person's illness - and a detriment - intoxication so that they don't know what they are doing.

Early 15th century South American explorer Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, a witness to tobacco use, gives a generally skeptical of tobacco and its impact on health. He mentions the intoxicating effects of the plant several times with disdain and says that the natives "hold this herb in great esteem, and cultivate it in their gardens and fields. They pretend that the use of it is not only wholesome, but holy."3 He notes that some Europeans use it, "especially those afflicted with the Mal de las Buvas [‘the illness of the buboes” - syphilis]. The latter say that while they are thus stupefied, they do not feel the pains consequent on their disease."4 However, he goes on to suggest that this is not a cure, just a temporary remedy. He also notes that African slaves use the herb because it "takes away the sense of weariness"5.

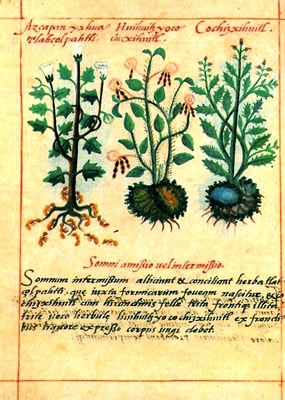

A book on native herbs published by native healer Martín de la Cruz which was translated into Latin by Juan Badiano and written in the book Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis at Tlaltelulco, Mexico in 1552. "The use of tobacco in an enema and in medicine to be taken by mouth and ingested seems to have been first suggested in this herbal."6

Folio 29r from Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis

Martin de La Cruz & Juan Badiano (1552)

The enema was a compound medicine containing tobacco, given to "one whose intestines rumble because of some flux in the abdomen". It was used for "one relapsing in sickness" after treatment with an emetic. Tobacco leaves were also one of the recommended topical applications for patients with gout, again being mixed with other plants.7

Writing in 1558, frere Andre Thevet provided a stronger link between tobacco use and health for the European medical community. He explains that tobacco "is very salubrious [healthy], they say, to distil and consume the superfluous humours of the brain. Further it makes hunger and thirst go away for some time."8 Humor theory was a central tenant of health up through and beyond the golden age of piracy, so this explanation would have been particularly appealing to period physicians.

In 1560, diplomat Jean Nicot experimented with tobacco to treat cancerous swellings (Noli mi tangere)9 as discussed in the formal history of tobacco at the beginning of this article. "Nicot, always on the look-out for such discoveries, was now fully convinced of the healing properties of the plant; he found, moreover, that when applied to the nose or forehead its cooling fragrance relieved his headache in a wonderful manner."10 Nicot mentions several other uses of tobacco to heal those around him including as a topical to repair his cook's severed thumb, for the removal of a long-standing ulcer on the leg of one of his pages and to eliminate ringworm in a woman's face.11 Such successful experiments led him to present the plant to the Queen of France as cure. She used it as snuff to treat both her and her son's persistent headaches.12

As tobacco found its way into Europe, the idea of tobacco as a medicine began to take root from the various publications and limited experiments performed with it. This set the stage for the concept of tobacco as a panacea.

1 Bishop Bartolome de las Casas, writing in 1527, cited in Footnote 2, Journal of the First Voyage of Columbus, 2003, p. 141; 2 Ramon Pane, “Treatise of Friar Ramon on the Antiquities of the Indians Which He as One Who Knows Their Language Diligently Collected By Command of the Admiral”, Columbus, Ramon Pane and the Beginnings of American Anthropology, Edward Gaylor Bourne, p. 20; 3,4,5 G. F. Oviedo, Historia General de las lndias, 1535, Libra V., Capit. 2; 6 Grace G. Stewart, “A History of the Medicinal Use of Tobacco 1492-1860”, Medical History, July 1967, p. 233; 7 Michael Wolfe, "Tobacco in an Aztec Herbal", www.tobacco.org, gathered from the De La Cruz-Badiano Aztec Herbal of 1552, Translation and Commentary by William Gates, gathered 10/1/18; 8 "Elle est fort salubre, disent ils, pour faire distiller & consumer les humeurs superflues du cerveau. Davantage prise en ceste façon fait passer la faim, & la soif pour quelque temps.", André Thevet, Les Singularitez de Ia France antarctique...", 1558, p. 60; 9 Charles Estienne and Jean Liebault, Joyfull Newes out of the newfound world, John Frampton, translator, 1580, f.42v – 43r; 10 Count Eugenio Courti, A History of Smoking, Translated by Paul England, 1932, p. 54; 11 Estienne and Liebault, f. 43r; 12 Berthold Laufer, "The Introduction of Tobacco into Europe", Field Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology, Chicago, Leaflet Number 19, 1924, p. 54

The History of Tobacco and Health - Tobacco as a Panacea (1570-1600)

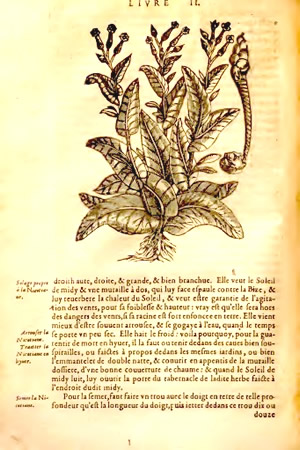

Tobacco's reputation as a panacea, capable of curing all diseases began to be built with the publication of Charles

A Now Familiar Illustration Featured in the 1683 Edition of

Estienne and Liebault's Chapter on Tobacco in

L'Agriculture et Maison Rustique

Estienne and Jean Liebault's L'Agriculture et Maison Rustique (Agriculture and the Rustic House). Physician Estienne wrote a variety of books on gardening and agriculture beginning in 1535 which were assembled by his son-in-law Liebault and expanded to include plants discovered in the new world. A chapter on tobacco was published in the 1570 edition of the book. Liebault used information on the plant's properties from Jean Nicot.

The chapter explained that tobacco "deserveth to stand in the first rank, by reason of his singular vertues, and as it were almost to bee had in admiration, as hereafter you shall understand."1 Maison Rustique goes on to mention a variety of health problems for which tobacco was useful. These include cancerous ulcers (Noli me tangere), old sores, ringworm, large scabs, humors in the head and dropsies (edemas).2 While these healing powers essentially echo Nicot's report to them, Estienne and Liebault's publication of this information gave them a wider audience.

Spanish physician and botanist Nicolás Monardes, "a celebrated physician of the University of Seville, who was employed at the time in investigating the various products which kept arriving from the West Indies with reference to their usefulness in medicine"3. Monardes published the first part of his book Historia medicinal de las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales (Medical study of the products imported from our West Indian possessions) in 1565 and, finding it well-received, published a second part in 1571 which contained a great deal of information on tobacco. A third part was published in 1574 along with the previous two parts. This book was to have a tremendous impact on understanding of the medicinal uses of tobacco, being translated into Latin, French, English, and Italian.4

While Estienne and Liebault limited their health advice to ideas presented by Jean Nicot, "

Artist: Hendrick Goltzius - Jean Nicot (1595)

Monardes advocated its internal and external use for a wide range of ailments."5 Unlike the other writers, he was a physician who had actually used tobacco and could report on his observations.6 In his book, Monardes enthused, about the plant's "mervellous medicinal virtues which it hath, now wee doe use of it more for his vertues then for his fairnesse [attractiveness in a garden]. For surely they are such which doe bring admiration."7

The long list health problems he recognized tobacco as being useful in healing include: fresh wounds, filthy wounds8, headaches, other 'griefes' of the head, any problem in any part of the body 'proceeding of a cold cause', problems of the breast, matter and rottenness of the mouth, inability to take deep breaths, cold or windy stomach problems, obstructions of the stomach and intestines, hardness of the stomach9, kidney stones, old swellings, 'evill of the Mother' and other female problems10, constipation in old people, worms of all kinds, joint pain, cold abcesses, toothaches11, chilblains, venemous wounds12, 'venemous Carbuncles', "woundes newly hurt and cuttes, strokes, prickes, or any other manner of woundes" and old sores13. He reported that it also took away weariness.14 In talking about the various health problems addressed, Monardes specified a variety of compound medicines which contained tobacco including instructions on how they were to be administered.

In 1577, John Frampton translated Monardes' and Estienne and Liebault's chapters on tobacco, publishing them in the book Joyfull Newes out of the newfound world. (It is from this work that most of the quoted information cited above comes.) "This became the textbook for English physicians who promptly accepted tabaco as the greatest panacea ever known to man. The part of Monardes in preparing the contents of the cornerstone for the panacea-of-panaceas structure was the cataloguing of about sixty-five diseases and other conditions which sana sancta [tobacco] would cure"15. Another result of Frampton's book, was that "when a physician saw a patient, it was more likely than not that the invalid would demand and/or that the physician would prescribe tabaco in the form of a decoction, an ointment, a powder, or a syrup."16

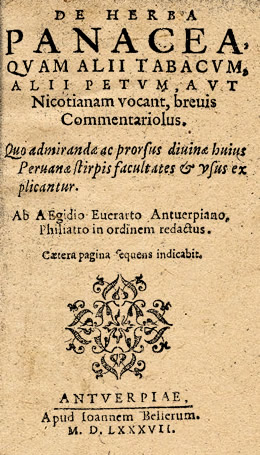

The Title Page of Gile's Everard's De Herba Pancea

From the Wellcome Collection (1687)

In Antwerp, Dutch physician Giles Everard published a book De herba panacea: quam alii tabacum, alii petum in 1587, which "collected a host of Galenic and chemical uses for tobacco and identified it as the long-sought panacea, the herb that would heal all ills."17 Written in Latin, the language used by physicians all across Europe, the title alone helped give tobacco's a reputation as a cure-all.

The introduction to the English interpretation of Everard's book, published in 1659, enthuses that tobacco's "sweet smell doth refresh the forces, and strengtheneth the brain, heart and stomach... and... it preserves their temperament and substance; and the vitall and animall spirits are renewed and made fit for natures operations, by a smoke joyned with that sweet s[c]ent, and sucked in with that Aromaticall Vapour."18 Like Monardes, Everard cites a number of illnesses that can be remedied by tobacco, suggesting it is useful for relieving tiredness19, treating dropsy20, diseases of the head, catarrhs (build-up of mucus or humors in the nose and throat), headaches21, cloudy vision, deafness, ozena (ulcers in the nose)22, redness of the face, toothaches23, ulcers of the gums, swelling of the throat, shortness of breath, diseases of the breast, old coughs caused by corrupt humors24, purging the phlegmatic humors, stomach pain24, kidney pain, stomach problems, surfeits (problems caused by over-eating and over-drinking)25, fainting, colic pain, iliac passion (blockage of the intestines)27, diseases of the liver, an obstructed spleen28, hemorrhoids, gout or sciatica29 and any health problem arising from a 'cold cause' (referring here to the humoral property of an illness).30

A Portrait Believed to be of Thomas Harriot (1602)

While not quite as loquacious in his praise for the health-giving aspects of tobacco, navigator and mathematician Thomas Harriot of the first Roanoke Colony in Virginia wrote in 1588 that the Spanish "take the fume or smoke [of tobacco] by sucking it through pipes made of claie into their stomacke and heade; from whence it purgeth superfluous fleame & other grosse humors, openeth all the pores & passages of the body: by which meanes the use thereof, not only preserveth the body from obstructions"31. He mentions that as long as they have not used it too much, "their bodies are notably preserved in health, & know not many greevous diseases wherewithall wee in England are oftentimes afflicted."32

Although a wide variety of other books were written during this period which helped build the reputation of tobacco as a panacea, these examples are sufficient to see how the plant was built into a wonder drug by botanical, historical and medical authors of the late 16th century.

1 Charles Estienne and Jean Liebault, Joyfull Newes out of the newfound world, John Frampton, translator, 1580, f.42r; 2 Estienne and Liebault, f. 44v; 3 Count Eugenio Courti, A History of Smoking, Translated by Paul England, 1932, p. 58; 4 Courti, p. 59; 5 David Harley, “The Beginnings of the Tobacco Controversy,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Spring 1993, p. 29; 6 Grace G Stewart, “A History of the Medicinal Use of Tobacco 1492-1860”, Medical History, July 1967, p. 236; 7 Nicholás Monardes, "Of the Tabaco and of His Greate Vertues", Joyfull Newes out of the new found world, 1580, John Frampton, translator, f.34r; 8 Monardes, f. 34v; 9 Monardes, f. 35r; 10 Monardes, f. 35v; 11 Monardes, f. 36r; 12 Monardes, f. 36v; 13 Monardes, f. 37r; 14 Monardes, f. 39v - 40r; 15,16 Stewart, p. 236; 17 Harley, p. 29; 18 "Panacea, Or The Universall Medicine; Being a Discourse and Discription or Tobacco, With its Preparation and Use", PANACEA, Or The Universall Medicine; Being a Discourse and Discription of TOBACCO, With its Preparation and Use, 1659, p. 32-3;18 Giles Everard, "Dr. Everard His Discourse Of the Wonderfull Effects & Operation of Tobacco", PANACEA, Or The Universall Medicine; Being a Discourse and Discription of TOBACCO, With its Preparation and Use, 1659, p. 32-3; 19 Evarard, p. 14; 20 Evarard, p. 17-8; 21 Evarard, p. 18; 22 Evarard, p. 19; 23 Evarard, p. 20; 24 Evarard, p. 21; 25 Evarard, p. 24; 26 Evarard, p. 25; 27 Evarard, p. 26; 28 Evarard, p. 27; 29 Evarard, p. 28; 30 Evarard, p. 29; 31,32 Thomas Hariot, A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia, 1588, p. 22