Tobacco and Medicine Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Next>>

Tobacco and Medicine During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 9

Tobacco Use and Tools - Snuff

Like pipe and cigar smoking, taking tobacco as snuff came from the American natives. The word snuff was defined around this time simply as "to snort; to draw breath in by the nose."1

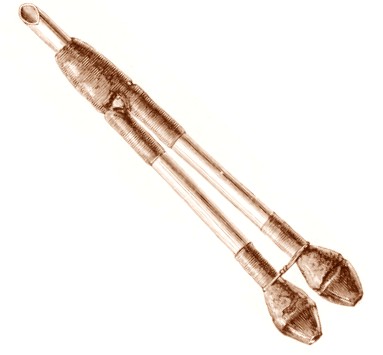

"'Tube for Taking Snuff", Venezuelan Guahibo Natives, From Handbook

to Ethnographical Collections, British Museum, 1910

In 1547, Oveido explained that the Taino natives used a forked pipe which they called a 'tabago pipe' to inhale burning tobacco into their nostrils. While this is not how tobacco snuff was used by Europeans, the idea is similar. A tube very much like that sketched by Oveido is found a book by the British Museum documenting their collections in 1910. This tube was created by the Guahibo tribe who are located in Venezuela, South America and the museum identified it as a "Tube for Taking Snuff"2.

Snuffing in the manner with which we are concerned is inhaling powdered tobacco into the nasal passages. The description of tobacco use provided by Ramón Pané - a Catalan monk who accompanied Christopher Columbus on his second voyage to the Caribbean between 1493 and 1496 - suggests that pipes were used by natives to inhale the powdered tobacco. Pané explains that "cogioba [tobacco] is a certain powder which they [the Taino natives] take sometimes to purge themselves... They take it with a cane about a foot long and put one end in the nose and the other in the powder, and in this manner they draw it into themselves through the nose and this purges them thoroughly."3 He elsewhere explains that they visit their gods by first "snuffing up into their nosthryles the pouder of the herbe called Cohobba [tobacco]... [after which] they say that immediately they see the houses turned topsie turvie, and men to walke with their heeles upward, of such force is this pouder, utterly to take away al sence."4 Pané brought some tobacco back to Portugal where the "the practice of sniffing the finely ground tobacco leaf (snuff) was... spread to the Iberian Peninsula."5

While snuff-taking was adopted by European nations from the native example, they do not seem to have copied the use of a tube or pipe to inhale it. As mentioned in the formal history of tobacco,

King Louis XIV Receiving the Doge of Genoa in Versailles (1685)

Jean Nicot presented tobacco in the form of snuff to French Queen Catherine de Medici to treat her headaches. Her son, François II, also suffered from chronic headaches and "was treated with snuff against severe headaches by the queen-mother, and the courtiers hastened to imitate the practice."6

Count Eugenio Courti explains that in early 17th century France "snuff-taking was pronounced a far daintier and more elegant method, and spread widely among the higher classes; the lower classes of the population went on smoking pipes, but their betters took more and more to snuff."7 Antiquarian Frederick William Fairholt says that snuff became "known as a luxury, and the gratification of a pinch was generally indulged in Spain, Italy, and France, during the early part of the seventeenth century."8 Fairholt explains that the high ranking noblemen of court of King Louis XIV "‘set the fashion’ of snuff, with all its luxurious additions of scents and expensive boxes."9

Snuff caught the interest of the English

A Gentleman Taking Snuff (Date Unknown)

court during the reign of English King Charles II (1649-51). It "took such a hold of the Court and the governing classes, the nobility and clergy, in France and England, that it almost entirely supplanted smoking. Snuff was fashionable; smoking was relegated to the middle and lower classes."10 Fairholt explains, "When William ascended the throne [1689] ... it was the fashion to be curious in snuffs; valuable boxes of all kinds were sported, and the beaux carried canes with hollow heads, that they might the more conveniently inhale a few grains through the perforations, as they sauntered in the fashionable promenades. Rich essences were employed to flavour it, and a taste in such scents was considered a necessary part of refined education."11

This continued during the reign of Queen Anne (1702-1714), where "snuff-taking increased to a great extent, and so did the varieties of mixtures, flavours, and names."12 French writer Francis Maximilien Misson says in a memoir of his travels that the 'smart fellows' in England "are call'd Fops and Beaux. ...They are Creatures compounded of a Perriwig and a Coat laden with Powder as white as a Miller's, a face besmear'd with Snuff, and a few affected Airs"13.

This makes it sound as if sailors (being decidedly in the lower class) would not have used snuff in the mid-17th century in England. However, if there is one thing that is clear about the history of the use of snuff in England, it is that nothing is entirely clear about the use of snuff in England. William Andre Chatto suggests that during the time of the Commonwealth in England (1649-1660), "many of our soldiers and sailors were accustomed to take a quid [a suitable amount of snuff] occasionally; a practice for which they had the example of Monk [George Monck], afterwards Duke of Albemarle, who, as he had commanded both as an admiral [1652-3] and a general [1649-1652], might be equally claimed by both services."14

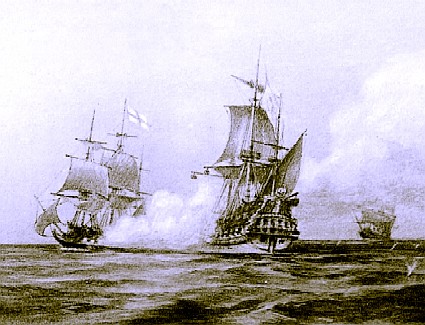

The English navy actually unwittingly contributed to the popularity of snuff among the common people in England in 1702. A number of Spanish and French ships were captured off Vigo Bay and several port towns including Port St. Mary taken during the War of the Spanish by the fleet

Artist: Ludolf Bakhuizen - Battle of Vigo Bay, National Maritime Museum (c.1702)

under the command of Admiral George Rooke. In his book, captain Nathaniel Uring recounts the action in taking the ships in Vigo Bay, mentioning that the Spanish used a fire ship against them with a "Store of Gun-powder being on Board,

[along] with a great Quantity of Snuff, soon after she was set

on fire it reached the Powder, and she blew up, which

scatter'd the Snuff all over the [British ship] Torbay, and put out the

greatest Part of the Fire"15.

As a result of these captures and raids, Rooke found "several thousand barrels and casks of fine snuffs" which were being sent to Spain from Havana.16 "This very large quantity of snuff was sold at the principal seaports, as ‘prizes,’ for the benefit of officers and crews... It was christened ‘Vigo snuff;’ and the popularity of the war, the name of the snuff, and the novelty of excessive cheapness, combined to induce a very general use of it."17 "Waggon loads of it were sold at Plymouth, Portsmouth, and Chatham for not more than three-pence or four-pence a pound. ...novelty being an English characteristic, arose the custom and fashion of snuff-taking; and, growing upon the whole nation by degrees"18. Joseph Haydn's A Dictionary of Dates proclaims that 'snuff-taking' "took its rise in England from the capture of vast quantities of sniff by sir George Rooke's expedition to Vigo in 1702."19

This sudden availability of cheap, ready-made snuff likely helped to make snuff available to

People Taking snuff, From Pandoras Box - A Satyr Against Snuff, (1718)

those outside the elite class. German physician and satirist Johann Heinrich Cohausen notes complained in 1720,

The world has adopted an absurd fashion. This is the excessive use of the tobacco snuff. All nations snuff tobacco. Tobacco is snorted by all classes, from the highest to the lowest. I have seen with bitterness how great gentlemen and their lackeys, noble people and those of the vulgar rabble, wood-choppers and handymen, beadles and beggars, take their snuff-boxes out with great grandeur and use them.20

We have seen how at least one Privateer ship had some users of snuff aboard around the same time.21 Yet there is little evidence in the period sailors journals to support the idea that snuff was anywhere near as popular as smoking among sailors. In his book Tobacco: Its History, Varieties, Culture, Manufacture and Commerce, E.R. Billings states, "Sea-faring men seldom take snuff: a sailor with a snuff-box is as rarely to be met with as a sailor without a knife."22

1 Samuel Johnson, A dictionary of the English language, 3rd ed., 1768, not paginated; 2 British Museum, Handbook to Ethnographical Collections, 1910, p. 277; 3 Ramón Pané, “Treatise of Friar Ramon on the Antiquities of the Indians Which He as One Who Knows Their Language Diligently Collected By Command of the Admiral, Columbus" , Ramon Pane and the Beginnings of American Anthropology, Translated by Edward Gaylor Bourne, 1906, p. 17; 4 Pané, “An Epitome of the Treatise of Friar Ramon Inserted By Peter Martyr In His De Rebus Oceanicis Et Novo Orbe”, Columbus, Ramon Pane..., p. 39; 5 A.G. Christen, B.Z. Swanson, E.D. Glover & A.H. Henderson, "Smokeless tobacco: The folklore and social history of snuffing, sneezing, dipping, and chewing", Journal of the American Dental Association, November, 1982, p. 822; 6 Berthold Laufer, "The Introduction of Tobacco into Europe", Field Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology, Chicago, Leaflet Number 19, 1924, p. 54; 7 Count Eugenio Courti, A History of Smoking, Translated by Paul England, 1932, p. 149; f8 Frederick William Fairholt, Tobacco Its History and Associations, 1862, p. 242; 9 Fairholt, p. 243; 10 Laufer, p. 187; 11 Fairhholt, p. 252; 12 Fairhholt, p. 258; 13 Francis Maximilien Misson, M. Misson's Memoirs and Observations in His Travels Over England, 1719, p. 16; 14 William Andrew Chatto/Joseph Fume, A Paper: - Of Tobacco, 1839, p. 52-3; 15 Nathaniel Uring, A history of the voyages and travels of Capt. Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 56; 16 James Jennings, A Practical Treatise on the History, Medical Propeties and Cultivation of Tobacco, 1830, p. 23; 17 Fairholt, p. 259; 18 Jennings, p. 24-5; 19 Joseph Timothy Haydn, A Dictionary of Dates, 1841, p. 476; 20 "Je Welt hat eine poßierliche Mode angenommen. Das ist der unmäßige Gebrauch des Schnupff-Tabacts. Tabact schnupffen alle Nationen. Tabact schnupfft man in allen Ständen, vom höchſten biß zum niedrigsten. Ich habe bißtoeilen mit Verwunderung gesehen, wiegroſſe Herren und ihre Laquanen wie vornehme Leute und die vom gemeinen Pöbel, Holzhacker und Handlanger, Besembinder und Bettel-Voigte ihre Tabatiere mit sonderlicher Grandezze heraus nehmen, und damit handhieren.", Johann Heinrich Cohausen, "To the reader", Satyrische Gedanken von der Pica Nasi oder der Sehnsucht der Lüstern Nase, 1720, not paginated; 21 See George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 408-9; 22 E. R. Billings, Tobacco: Its History, Varieties, Culture, Manufacture and Commerce, 1875, p. 258

Tobacco Use and Tools - Making Snuff

Just as tobacco for pipes was originally cut directly from the carot or twist of tobacco, so snuff was originally rasped from the same source. "During the 17th and early 18th centuries, most everyone made his own snuff, grinding up dried and tightly rolled tobacco leaves, called a 'cerotte;' [carot] by means of an iron hand grater or rasp."1 Since snuffers had to grate their own tobacco, they were required to have a rasp available. Like the ornate stoppers or tampers used by pipe smokers, "

A Gilt-Silver Snuff Grater Closed And Opened to Show Grater. Tobacco was Grated and the

Snuff

Fell into the Basin Below the Rasp. It was Poured Out Through the Hole on the Top

From the British Museum Collection (late 17th century)

rasps were carried in the waistcoat pocket, and became articles of luxury, being carved in ivory and variously enriched."2

Frederick William Fairholt explains the procedure for using a snuff rasp. "If the snuff-maker wished to fill his box, he rasped a sufficient quantity to fill the large receptacle at the bottom; if he wished for a pinch his ‘fresh and fresh,’ he shook out a small quantity into the little shell at the top, which was not large enough to admit the fingers for a pinch, it was therefore turned out upon the back of the hand, and so snuffed up the nose."3

Fairholt notes that when tobacco was rasped, the result was a 'rough powder' which "was known as tabac en poudre or tabac rape; the latter term we still retain in the name of one kind of snuff -rappee- long after it has ceased to bear its legitimate sense of grated tobacco."4

Some authors suggest an elaborate procedure for the treating snuff for personal use once it had been rasped. Writing in the late 17th century, John White recommended the following:

To make Snuff, and how to cleanse it. Put your Tobacco dust in a strong Linnen-cloth, soak your Tobacco-dust in a Pail of Water, only once in 24 Hours; then let the Water out, and squeeze the Snuff well in the Cloth, then dry it on Wicker Hurdles in the Sun, stirring it carefully whilst it's a drying; being dry, pour sweet Water over it, as Rose-water, or any other you like best, and make it as a Paste; dry it again, and pour more Rose-water to it, and dry it again, and it's fit to receive what Smell you please. Mint dry'd and powdered, makes a pleasant Snuff; or some Rose leaves and Cloves distill’d and powder’d, and put to your Snuff; or what Herb or Flower you please.5

Adding Scent to Snuff, From

Abraham Delvalle's Trade Card

(1750)

As White suggests, snuff was often 'flavored' by the addition of herbs, oils and spices. Like so many other tobacco practices, this originated with the natives, in this case those in Brazil. "One of their methods was to make a cup in a rosewood block and with a pestle of the same wood pulverise the leaves of tobacco into the finest powder, this friction giving the most delicate rosewood

aroma to the hot snuff. The snuff, still hot, was put into bone tubes the ends of which were plugged to preserve the rich fragrance."6

The practice of scenting snuff was expanded upon over time, resulting in a wide variety of snuffs being available around the golden age of piracy. Writing in 1668, Jean le Royer de Prade mentioned in his book Discours du Tabac that snuff could be mixed with "pyrethrum (daisies), cyclamen flowers, Roman wine infused with vinegar for four days, ginger, pepper, cloves, cubebs, cumin, mustard seeds, angelica, burnt wood or coconut & spurge"7. A book on preparing beauty products for women published in 1705 called Beauties Treasury includes information on how to perfume snuff. It explains that "the properest and most grateful are the Flowers of Jessamine, Orange, Damas and Musk Roses, Tuberoses, Violets and such like sweet-scented Flowers"8. The book includes several recipes for specific types of snuff which use ambergris, musk, civet, sugar, perfume, oil of sweet almonds, tragacanth gum, rosemary, marjoram, mace, lavender and benjamin.

Beauties Treasury details the procedure for adding scents to snuff. "Take a Wooden-Box sufficient in Bigness for your Purpose, line it with dry Paper, and lay in a Bed of Snuff about an Inch thick, then Laying of Flowers finely pick't, and so proceed till you have laid all your Layings, shut it down close, and let it remain twenty four Hours, then sift your Snuff... and so continue to do four or five times"9. Fairholt adds that a mortar and pestle were sometimes used "to allow the more perfect mixing of the scents so commonly used."10

Photo: Marco Almbauer - Yellow and Red Ochre Pigments

Snuff could also be colored. Beauties Treasury explains that this is done by adding "Oaker [ochre - a natural clay pigment] Red or Yellow about three Ounces or more, as the Occasion may require, mix it with fine White Chalk, to temper the Colour a little, grind them with a Muller [a weight used to grind pigment] on a [flat] Marble-stone"11. A pint of coloring paste is made by combining the pigmens with oil of sweet almonds, water and gum tragacanth. After this, "take what Quantity of Snuff you please, well cleansed, and put it into a Pan or Vessel, and pour over it the Colour, working and

well mixing it with your Hands, that it may become a kind of a Paste not very hard nor too soft, and so leave your Snuff in the Colour till the next Day"12. Fairholt dryly notes, "After all this [washing, perfuming and coloring] was done, the last flavour of tobacco was destroyed"13.

As seen by the capture of the snuff at Vigo and St. Mary's, the Spanish sent tobacco from Cuba which had already been made into snuff and packed in barrels. "Spain, Portugal, and France early in the Seventeenth Century became noted as the producers of the finest kinds of snuff."14 Fairholt notes that "Spanish snuff was flavoured with musk, civet, and essence of millefleurs. Essence of cedar and bergamot was also used for snuffs bearing the name of each. Neroly was named from the essential oil distilled from orange-flowers."15

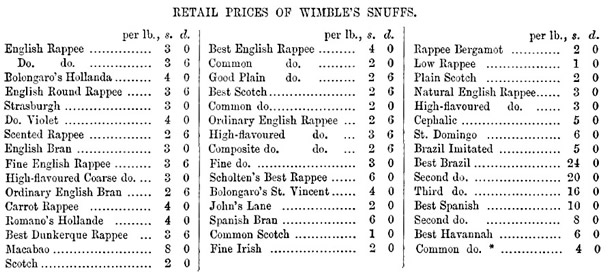

Retail Prices of Wimble's Snuffs from 1740, From Tobacco: Its History and Associations, Fairholt (1862)

Of course, there was a good reason for scenting snuffs. "Some of the more highly perfumed snuffs sold for thirty shillings a pound, while the cheaper kinds, such as English Rappee and John's Lane, could be bought for two or three shillings per pound."16 Fairholt includes a list of retail snuff prices published by the London-based Wimble and Company of Fenchurch Street in 1740 which can be seen here.

The manufacture of snuff did have the downside of shielding the user from seeing what quality of tobacco was used to make their snuff. Fairholt explains that rappee snuff

is generally considered in the trade to allow of most unfair mixing; all portions of damaged tobacco, the sweepings of the tobacco warehouse, &c, are incorporated in this. It is impossible to hinder small fragments of tobacco from falling on the floor of the manufactory; and the workmen's feet are always carefully scraped into a box, which afterwards helps to fill the more elegant box of the snuff-taker. ...When the whole is placed in the ‘snuff bin,’ it is well wetted, and allowed partially to ferment; as it heats it is turned with a shovel, and the mass ultimately assumes that dark colour valued in rappee; the blacker kind of that snuff being subjected to a longer residence in the bin.17

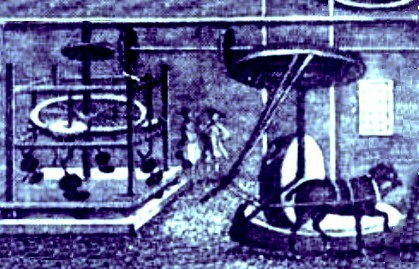

A Horse-Powered Snuff Mill, From Abraham Delvalle's Trade Card (1750)

Such prepared snuffs likely became popular in England in the early part of the 18th century, due at least in part to the introduction of the barrels of Vigo snuff. "It was not long [after the Vigo capture] before ready-made snuffs appeared on the domestic market [in England]"18. Fairholt points out that snuff "made by hand-labour was not supplied equal to the demand, it was also too expensive, and snuff-mills turned by horses were invented."19 It is not clear when these 'automated' snuff mills appeared; the 1750 trade card of Abraham Devalle, snuff-maker in London, shows a horse powered snuff-making machine (seen at left).

Some time in the early or mid 18th century, English manufacturers also employed water-powered mills, "similar to those that produced flour, to grind the tobacco which gave it a finer feel that was close to the grind of baking flour."20 A variety of such water-powered mills still stand in Britain today including at Stodday, Lancashire, Stapleton,

Photo: Mick Knapton - Sharrow MIlls, Home of Snuff Producer Wilsons & Co. in 2014

Chetnole, the lower mill at Carshalton, a water mill at Morden and another at Bewdley, the Kenthshare Lane Mill at Winford, the Kendal Mill at Helsington Laithes, the Sharrow Mill at Porter, Sheffield and the Culvett Mill at Wraysbury21.

Of these mills, one of the earliest known was the Sharrow Mill, established around 1737 in England to mass produce snuff tobacco.22 (Of the other mills shown in the list whose approximate origin dates have been specified, the Morrow mill dates to about 175023, the Bewdley mill very roughly to 178524 and the Carsharton mill to about 178625.) So it would appear that automated milling was a post-GAoP phenomenon. Of course, other mills almost certainly existed which no longer stand and the dating of any of them seems to be rather difficult based on the information known about those still standing.

1 A.G. Christen, B.Z. Swanson, E.D. Glover & A.H. Henderson, "Smokeless tobacco: The folklore and social history of snuffing, sneezing, dipping, and chewing", Journal of the American Dental Association, November, 1982, p. 823; 2 Berthold Laufer, "The Introduction of Tobacco into Europe", Field Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology, Chicago, Leaflet Number 19, 1924, p. 41; 3 Frederick William Fairholt, Tobacco Its History and Associations, 1862, p. 245; 4 Fairholt, p. 244; 5 John White, Art's Treasury of rarities and curious inventions, 4th ed, 1695, p. 152; 6 Mattoon M. Curtis, The Book of Snuff and Snuff Boxes, 1935, p. 25; 7 "On mêle encore avec le Tabac en poudre la pyretre, le cyclamen, le nieile Romaine infusee en du vinaigre pendant quatre jours, le gingembre, le poivre, le girofle, les cubebes le cumin, la graine de moutarde, l'Angelique, le bois faint ou l'ellebore, & l'euphorbe...", Edme Baillard (Jean le Royer de Prade), Discours du Tabac, 1668, p. 91-2; 8 J.W., Beauties treasury, or The ladies vade mecum, 1705, p. 105; 9 J.W., p. 105-6; 10 Fairholt, p. 252; 11 J.W., p. 108; 12 J.W., p. 108-9; 13 Fairholt, p. 247; 14 E. R. Billings, Tobacco: Its History, Varieties, Culture, Manufacture and Commerce, 1875, p. 222; 15 Fairholt, p. 248; 16 Billings, p. 223; 17 Fairholt, p. 314-5; 18 Christen, et. al., p. 823; 19 Fairholt, p. 315-6; 20 "History of English Snuff", Smokeless Afficianado Website, gathered 9/12/18; 21 The Mills Archive Website identifies 10 extant water-powered snuff mills in England as seen here, www.millsarhive.org, gathered 9/12/18; 22 "Sharrow Mills", Historic England Website, gathered 9/12/18; 23 "Snuff Mill", Wandle Valley Park Website, gathered 9/12/18; 24 "Bewdley Snuff MIll", Revolutionary Players website, gathered 9/12/18; 25 "The Snuff Mill, Carshalton", Wandle Industrial Museum website, gathered 9/12/18

Tobacco Use and Tools - Snuff Containers

Like many other things to do with tobacco, snuff boxes had their origin in the practices of

A German Snuff Bottle, Iron, From the MET Museum of Art (1690)

the natives. Mattoon Curtis explains that snuff boxes arose from "[t]he Indian custom of carrying tobacco in small animal skins or leather bags decorated with coloured thread or paints, and later with beads"1. Snuff was carried in a variety of containers in Europe such as bags, pouches, bottles and boxes. Although snuff bottles are often associated with the orient, Curtis explains that they "were not uncommon in Europe even in the seventeenth century." He goes on to cite examples of bottles being used in Norway, Germany and Italy, but also admits "they never became widely popular, being less easily carried than the box."2

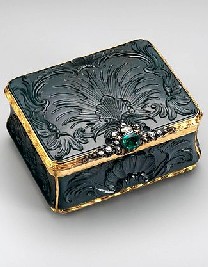

The snuff boxes used in England, particularly amongst the elite, were often highly decorated and expensive. "The most expensive materials were employed in the manufacture of snuff-boxes, such as agate, mosaics, and all kinds of rare wood, while many were of gold, studded with diamonds."3

The lavishness of snuff boxes is highlighted in the 1718 book-length poem Pandora’s Box; a Satyr against Snuff. The anonymous author rather sarcastically opines:

A French Snuff Box, Carved Gold Frame, set with small

diamonds rubies and emeralds (ca. 1750)

For Females fair, and formal Fops to please,

The Mines are robb'd of Ore, of Shells the Seas,

With all that Mother Earth and Beast afford

To Man, unworthy now, tho' once their Lord:

Which wrought into a Box, with all the Show

Of Art the greatest Artist can bestow;

Charming in Shape, with polish'd Rays of Light,

A Joint so fine it shuns the sharpest Sight;

Must still be graced with all the radiant Gems

And precious Stones that e'er arrived in Thames.

On which Artificers, consulting Gains,

Have crack’d their own to strike others Brains.

Within the Lid the Painter plays his Part,

And with his Proves his matchless Art;

There drawn to Life some Spark or Mistress dwells,

Like Hermits chaste and constant to their Cells.4

Among the wide variety of materials used to make snuff boxes were platinum, gold, crystal, lead, iron, almost every kind of wood, bamboo, gourd, amber, all sorts of shells including those of the pearl oyster and amphibian tortoise, leather, bones, horns, tusks, ivory, glass, porcelain and papier-mâché.5

Snuff Box Manufacturer, From Cyclopediae, Vol. 9, By Denis Diderot (1771)

Snuff boxes came in a variety of shapes and sizes. Curtis comments that "the artists worked with freedom, not only in form, but in material, colour, and decoration."6 He also says that the size of these boxes ranged "from the tiny ones carried by milady in hand or bag or on chatelaine to the generous table and mantel boxes for the benefit of the family and guests."7

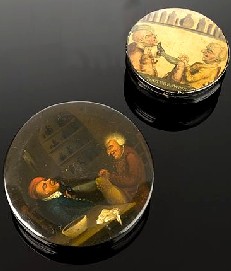

Snuff boxes sometimes also had elaborate paintings on them. Frederick William Fairholt note, "Boxes decorated with paintings were great favourites in the days of Anne [1702-1714] and George I [1714-1727]."8

Below is a small gallery of snuff boxes showing different designs and being constructed from a variety of materials which have been dated to around the golden age of piracy.

|

|

|

| Snuff Boxes, From Left: Gold and Platinum with jewels (early 18th century), Tortoiseshell and Silver (early 18th century), Tortoiseshell with Mocha Stone Inlay (18th century) | ||

|

|

|

| Snuff Boxes, From Left: Shell, Carnelian and gold with hunting scene (c. 1730), Gold with Enamel Painted Kitchen Scenes (18th century), Silver with Painted Tooth Extraction Scenes (18th century) | ||

As interesting as these images are, they show the more expensive examples of snuff boxes, meaning that they would almost certainly not be the type of container a sailor would have (provided he was among the few who used snuff). Such boxes which would likely be used by the upper classes.

Artist: Robert C. Leslie - Woodes Rogers' Ship Duke Takes a Vessel (1889)

However, elaborate snuff boxes do have a place among the sea-going marauders of the period; they are mentioned as plunder captured by pirates and privateers. Woodes Rogers notes that among the plunder they had taken by August of 1709 there were "Silver-handled Swords, buckles, Snuff-boxes, Buttons and Silver Plates in use aboard every Prize we took, and [were] allow’d to be Plunder [under their articles]... "besides 3 lb. 12 {ounces} of Gold, which was in Rings, Gold, Snuff-boxes, Earrings, and Gold Chains, taken about Prisoners."9. When pirates Phineas Bunce and Dennis Mccarty mutinied in the Bahamas, setting the men not willing to join them on shore, they brought some of them back on board the ships "to make them discover where some things lay, which they could not readily find, particularly Mr. Carr's watch and silver snuff-box"10. James Carr was the supercargo (the ship's owner's representative) of the voyage and a former midshipman on a British Royal Navy man-of-war.

1 Mattoon M. Curtis, The Book of Snuff and Snuff Boxes, 1935, p. 79; 2 Curtis, p. 80; 3 E. R. Billings, Tobacco: Its History, Varieties, Culture, Manufacture and Commerce, 1875, p. 222; 4 Pandora’s Box; a Satyr against Snuff, 1718, p. 6-7; 5 Curtis, p. 84-6; 6 Curtis, p. 81; 7 Curtis, p. 82; 8 Frederick William Fairholt, Tobacco Its History and Associations, 1862, p. 292; 9 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 2004, p. 234; 10 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 630