Tobacco and Medicine Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Next>>

Tobacco and Medicine During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

Tobacco Plant (Continued)

Tobacco Plant Farming

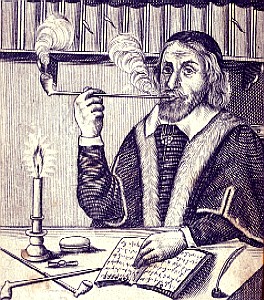

Giles Everard, From Panacea (1659) A number of authors discuss the planting and care of tobacco. Among them are the two French authors Charles Estienne and Jean Liebault, who provide a great deal of information in their 1570 book La Maison rustique, which was translated into English by John Frampton in 1577 and then again in 1580 in his book Joyfull Newes out of the new found world. Dutch physician Giles Everard also provides guidance in his 1587 book De herba panacea, the 1659 English translation of which is used here: Panacea, or the Universal Medicine. Closer to the golden age of piracy, Ephraim Chambers reliable Cyclopedia of 1728 lays out a practical plan for tobacco farming. Finally, although it was published almost fifty years after the GAoP, Jonathan Carvers' 1778 book A Treatise on the Culture of the Tobacco Plant provides insight on farming tobacco not found in the other sources. (The 1779 second edition is used here.)

All of these authors are quite concerned about the type of land where tobacco is planted. Estienne and Liebault say tobacco requires "a fat grounde finely digged, and in colde Countreys very well dounged, that is to say, a

grounde in which the doung must be so wel mingled and incorporated, that it be altogether turned into earth, & that there appeare no more doung."1 Everard focuses more on the situation that the earth. "Let the Lands upon which you sow it be long, and about three foot broad, that by the furrows between he may pass on both sides"2. Encyclopedist Chambers adds that

Photo: Susanne Bollinger - Young Nicotiana Tabacum Plants on Cuba Plantation

"in the Caribee Islands, Virginia, &c. ...they are forced to mix Ashes with the Soil, to prevent its rising to[o] thick."3 Writing after the GAoP, Carver digs deeper into the soils where tobacco flourishes:

The best ground for raising the plant is a warm, kindly, rich soil, that is not subject to be over-run with weeds; for from these it must be totally cleared. The soil in which it grows in its native climate, Virginia, is inclining to sandy, consequently warm and light... Other kinds of soils may probably be brought to suit it, by a mixture with some attenuating species of manure, but a knowledge of this must be the result of repeated trials.4

It is notable that he suggests that Virginia is the 'native soil' when referring

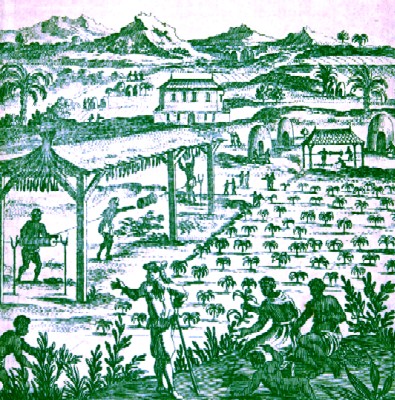

Artist: Alain Manesson Mallet - Tobacco Plantation (1685) to Nicotiana tabacum, when it was actually the native soil for Nicotiana rusticum. However, N. tabacum had been grown there for over a hundred and fifty years and N.rusticum was no longer being farmed for smoking, chew or snuff for the most part.

Estienne and Liebault emphasize the need for a location with an abundance of warmth and sun where the plant grows. They even recommend that it "be planted by a wal, which may defende it against the North winde recovering the heate of the Sunne against it, being a warrant unto the said hearbe against the tossing up of the winde, because of the weaknes and highnes therof."5

The actual planting of the tobacco seed requires "a hole in the ground [made] with your finger, as deepe as your finger can reache, then cast into that hole 40. Or 50. Grains of the sayde Seede together stopping againe your hole"6. Estienne and Liebault warn that because the seed is so small, "if there bee put in the hole but three or foure graynes thereof, the earth would choke them"7. Everard is not so generous with the seeds, recommending that the reader "dig the earth with your finger, or a little stick, and make a hole in it, and put into it ten or twelve grains, and put a piece of Oxe dung both at the botom and top of them."8

Putting 30 to 40 Tobacco Seeds in One Place

May Contribute to the Need for Replanting... Estienne and Liebault say that tobacco must be replanted, apparently in an effort to untangle the roots. Their method is to cut "with a great knife a greate compasse within the earth rounde about the saide place, and lift up the earth together with the Seede, and cast it into a payle of water, so that the earth bee separated, & that the little twigges may swimme above the water, then shal you make them without breaking, the one after the other"9. Then the individual plants are to be replanted "leaving foure foote space from one Twigge to another"10. Ephraim Chambers recommends a similar procedure. "When 'tis risen to a convenient Pitch, they transplant it, much as we do Lettuce, only at a Distance of three Feet, and in a Soil prepared with great Care"11.

A variety of care suggestions are provided for tobacco when it is growing. Estienne and Liebault warn that it "must be weeded very carefully, seeing the least root of any other herb coming near it hinders its growth."12 Chambers likewise advises continuous weeding after the tobacco has been replanted. He also says the grower must "water it every Day, and on very hot days cover it up to prevent its being scorched by the Sun."13

Chambers also says the stem of the plant must be frequently cleansed "and the lowest Leaves and the Suckers it puts forth, taken off, Ten or Fifteen of the finest leaves may have all the Nourishment."14 Jonathan Carver similarly orders his reader "to nip off the sprouts that will be continually springing up at the junction of the leaves with the stalks. This is termed ‘succouring or suckering the tobacco,’ and ought to be repeated as often as occasion requires."15 He elsewhere explains that this makes the remaining leaves better and stronger.

Photo: Jarod E. Stephens (Used with Permission)

Topping the Nicotiana Tabacum Plants, From www.jarodestephens.com

Pruning is also recommended by Estienne and Liebault; their advice is to cut off the top of the plant "to hinder the stalks and leaves from shooting up too high, that the whole plant may receive greater strength from the earth."16 Carver likewise orders 'topping the plant' when "it has risen to upwards of two feet... as this expansion, if suffered to take place, would drain the nutriment from the leaves, which are the most valuable part, and thereby lessen their size and efficacy"17. He goes on to say that some people cut the top when there are fifteen leaves on the stalk, or, when more potent tobacco is desired, "this is done when it has only thirteen; and sometimes, when it is chosen to be remarkably powerful, eleven or twelve leaves only are allowed to expand."18

Carver alone talks about a pest specific to the tobacco plant, although this must surely have been a problem from all along. He says, "The last, and not the least concern in the cultivation of this plant, is the destruction of the worm that nature has given it for an enemy, and which, like many other reptiles, preys on its benefactor."19 Carver explains that each leaf must be carefully examined for wounds caused by this insect. (It is not, in fact, a reptile.) When found, the insect must be located and

Photo: Daniel Schwen - Tobacco Hornworm (Manduca Sexta Larvae) crushed, which he refers to as 'worming the tobacco'. This 'tobacco worm' is actually the larval stage of the tobacco moth or Manduca sexta. Carver notes that it is about the size of a man's finger,

indented or ribbed round at equal distances, nearly a quarter of an inch from each other, and having at every one of these divisions, a pair of feet or claws, by which it fastens itself to the plant. Its mouth, like that of the caterpillar, is placed under the fore-part of the head. On the top of the head, between the eyes, grows a horn about half an inch in length, and greatly resembling a thorn; the extreme part of which is in colour brown, of a firm texture, and sharp pointed. By this horn, as before observed, it is usually plucked from the leaf. It is easily crushed, being only, to appearance, a composition of green juice inclosed by a membranous covering, without the internal parts of an animated being. The colour of its skin is in general green, interspersed with spots of a yellowish white; and the whole covered with a short hair scarcely to be discerned.20

1 Charles Estienne and Jean Liebault, “La Maison rustique”, Joyfull Newes out of the new found world, 1580, John Frampton, translator, p. f.43v-44r; 2 Giles Everard, Panacea, or the Universal Medicine, 1659, p. 17; 3 Ephraim Chambers, “Tobacco”, Cyclopedia, Vol. 2, 1728, p. 221; 4 Jonathan Carver, A Treatise on the Culture of the Tobacco Plant, 1779, p. 13; 5,6,7 Estienne and Liebault, f.44r; 8 Everard, p. 17-8; 9 Estienne and Liebault, f.44r; 10 Estienne and Liebault, f.44v; 11 Chambers, p. 211; 12 Estienne and Liebault, f.43v-44r; 13,14 Chambers, p. 211; 15 Carver, p. 22; 16 Estienne and Liebault, f44r; 17,18 Carver, p. 21; 19 Carver, p. 22; 20 Carver, p. 26

Tobacco Plant Harvest and Drying

For harvesting, physicians Charles Estienne and Jean Liebault explain that tobacco plants "hateth the cold" and must be protected from it, although they do not provide details about the harvest.1

Harvesting Tobacco, From Oeconomus prudens et legalis, By Franz Philipp Florinus, p. 605 (1722) |

Writing in 1572 about his observations of the South American natives, Italian merchant Girolamo Benzoni simply says "[w]hen these leaves are in season, they pick them, tie them up in bundles"2. English encyclopedist Ephraim

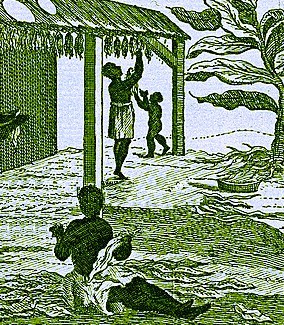

Tobacco Leaves Being Sorted, Dried and Cured,

From

Universal Magazine, Wellcome Collection (1750)

Chambers provides more detail, explaining that the leaves are to be picked when ripe "which is known by their breaking when bent"3.

American author and explorer Jonathan Carver provides much more detail about the harvest. He suggests that the leaves should be harvested "on the first morning that promises a fair day, before the sun is risen"4. He recommends using an axe or long knife "and holding the stalk near the top with one hand, sever it from its root with the other, as low as possible; Having done this, lay it gently on the ground, so as not to break off the leaves, and there let it remain exposed to the rays of the sun throughout the day, or until the leaves are entirely wilted"5. Chambers is more specific, stating that the leaves should be "left to dry two or three Hours in the Sun"6.

Former buccaneer Alexandre Exquemelin explains that once the tobacco has dried in a sun for the requisite time, buccaneer tobacco farmers "prepare certain apartments of fifty or sixty feet long, and thirty or forty broad; these they fill with poles and rafters, and on them lay the green tobacco to dry."7 Estienne and Liebault note that the leaves are to be "dryed in shadow, and hanged up in the house, so that there come neither Sunne, winde, nor fire thereunto"8. Carver suggests a much more complex procedure, which may have come about after the golden age of piracy since his book was first published in 1778. He explains,

Photo: Wiki User , Gorupdebesanez - Tobacco drying in Pinar del Río

the plants must be laid in heaps, or rather in one heap; if the quantity be not too great, and in about twenty-four hours they will be found to sweat. But during this time, when they have lain for a little while, and begin to ferment, it is necessary to turn them; bringing those which are in the middle to the surface, and placing those which were at the surface, in the middle, that by this means the whole quantity may be equally fermented. The longer they lie in this situation the darker coloured the tobacco becomes. This is termed 'sweating the tobacco.'9

Once this is completed, Carver says "the plants may be fastened together in pairs, with cords or wooden pegs, near the bottom of the stalk, and hung across a pole, with the leaves suspended, in the same covered place, a proper interval being left between each pair."10 The plants are to be left this way for about a month. When they have been thoroughly dried, they are taken down. Benzoni suggests another way to dry tobacco leaves. He explains that the method the natives used to dry small amounts of it was simply to "suspend them near their fire-place till they are very dry"11.

Once the leaves are dry, Exquemelin says the buccaneer farmers "strip the leaf from the stalks" and roll them for storage. Carver again gives a somewhat more complex explanation of this which is probably more accurate for mass farming of the plant. "When the leaves are stripped from the stalks, they are to be tied up in bunches or hands, and kept in a cellar, or any other place that is damp"12. Chambers affirms this in his Cyclopedia.

1 Charles Estienne and Jean Liebault, “La Maison rustique”, Joyfull Newes out of the new found world, 1580, John Frampton, translator, f.44r; 2 Girolamo Benzoni, History of the New World, 1572, Translated by Rear-Admiral W Smyth, 1857, pp. 80; 3 Ephraim Chambers, “Tobacco”, Cyclopedia, Vol. 2, 1728, p. 221; 4,5 Jonathan Carver, A Treatise on the Culture of the Tobacco Plant, 1779, p. 28; 6 Chambers, p. 221; 7 Alexandre Exquemelin, The Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 44; 8 Estienne and Liebault, f.44v; 9 Carver, p. 29-30; 10 Carver, p. 30; 11 Benzoni, p. 80; 12 Carver, p. 31

Dried Tobacco Leaf Processing

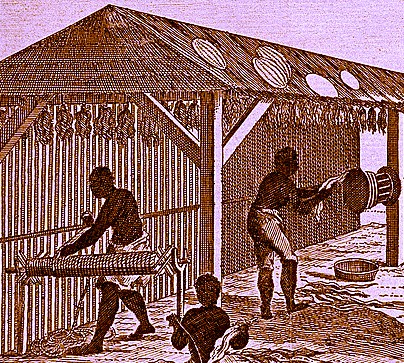

Tobacco Leaves Being Stripped and Twisted,

From

Universal Magazine,

Wellcome Collection (1750)

Once the tobacco leaves have been dried, Ephraim Chambers says they are to be "steep'd in Sea-water, or for want thereof, in common Water, are twisted, in manner of Ropes; and the Twists form’d into Rolls, by winding them with a kind of Mill around a Stick."1

Jonathan Carver discusses the method for forming twists of tobacco in the American colonies. "Being possessed of a tobacco-wheel, which is a very simple machine, they [American colonists] spin the leaves, after they are properly cured, into a twist of any size they think fit, and having folded it into rolls of about twenty pounds weight each, they lay it by for use. In this state it will keep for several years, and be continually improving"2. This process can be seen in the image at left and below. Chambers adds, "The Marks of good Twist Tobacco, are a fine shining Cut, and agreeable Smell; and that it have been well kept."3

Rolling and Spinning Tobacco, From Oeconomus prudens et legalis, By Franz Philipp Florinus, p. 607 (1722) |

Alexandre Exquemelin discusses a different process for preparing tobacco for shipment: "it to be rolled up by certain people, who are employed in this work and no other"4. Rolling tobacco likely refers to making a carot of tobacco leaves. Jonathan Carver explains that the Illinois Tribe makes carots of the tobacco when preparing it. This "is done by laying a number of leaves, when cured, on each other, after the ribs have

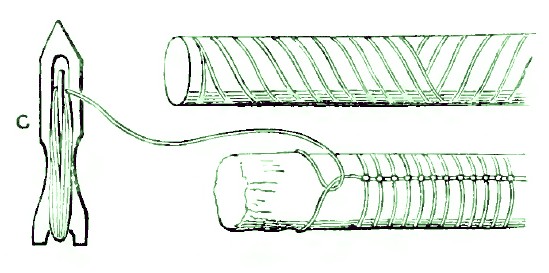

Artist: Frederic William Fairholt - Making a Tobacco Carot According to the French Method (1862)

been taken out, and rolling them round with packthread, till they become cemented together. These rolls commonly measure about eighteen or twenty inches long, and nine round in the middle part."5 Antiquarian and wood engraver Frederick William Fairholt shows the method for creating a tobacco carot according to the "French method" in his book using pack-thread, as seen in the image at right. He explains that his image details "the workman's implement at c, and the mode by which the knot was secured. It is copied from an engraving dated 1768. These carottes were sometimes steeped in new rum or sugar, to give richness to the flavour of the leaf, and were in much favour with sailors for chewing."6

Fairholt explains that once the leaves were rolled, "some large leaves were used to cover the whole"7. The rolled or twisted tobacco was then loaded into hogsheads, which were a type of wooden cask made to hold about 140 liters, or 30 gallons.8 Referring to twists, Chambers says, "In this Condition, ‘tis imported from Europe, where ‘tis cut by the Tobacconists, for Smoaking; form’d into Snuff, and the like."9

1 Ephraim Chambers, “Tobacco”, Cyclopedia, Vol. 2, 1728, p. 221; 2 Jonathan Carver, A Treatise on the Culture of the Tobacco Plant, 1779, p. 6; 3 Chambers, p. 221; 4 Alexandre Exquemelin, The Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 44; 5 Carver, p. 7; 6 Frederick William Fairhholt, Tobacco Its History and Associations, 1862, p. 310-1; 7 Fairhholt, p. 310; 8 Count Eugenio Courti, A History of Smoking, Translated by Paul England, 1932, p. 177; 9 Chambers, p. 221