Tobacco and Medicine Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Next>>

Tobacco and Medicine During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 2

A Brief History of Tobacco's Entry Into the Old World - Informal History

“The sailors and merchants of the coastal towns, whose business took them across the sea to distant lands, had discovered that the traffic in tobacco was extremely lucrative, and, once introduced into a country, it created a strong and growing demand; consequently they lost no time in taking a store of it with them wherever they went,

Sailor in Port, Smoking and Drinking, From a Tobacco Paper

for Newmans best Virginia tobacco, British Museum (18th c.)

and thus they introduced smoking to nations which had hitherto been ignorant of it." (Count Eugenio Courti, A History of Smoking, Translated by Paul England, 1932, p. 143-4)

As mentioned in the previous section, the history of tobacco's entry into the old world from the new takes two paths. Where the first was the formal transmission of the plant to royalty via the New America explorers, the second route was courtesy of the regular sailor who had taken up the habit of smoking while visiting the new world. Unfortunately for posterity, the actions of such men are rarely recorded in the historical records. Occasional mentions of them and hints of their behavior appear, particularly in later histories looking back, although it is nearly impossible to accurately track their true involvement in the introduction of tobacco use.

The first man to visit a native village in the Caribbean was also one of the first to introduce tobacco smoking to his home village. Rodrigo de Jerez, one of the two men sent by Columbus to explore Cuba in 1492 is reported to have publicly smoked in his native town of Ayamonte, Spain. The locals, "on seeing a cloud of smoke suddenly issue from his mouth and nose, were horribly alarmed and, concluding that the Devil had got hold of him, hurried off to the priest, who referred the matter to the Inquisition."1 He summarily thrown into prison, not being released for seven years, by which time smoking had apparently become more common in Spain.

This illustrates the impact a regular sailor could have in the old world places in which he stopped. Unfortunately the sailors' use for tobacco is typically only mentioned in passing, such as the caption found in the previous

El Tabacco, From Nicholas Monardes' Segunda parte del

libro

de

las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales, f31v (1580)

section in Matthias l'Obel's 1570-1 book. Here, the simple addition of "& neucleri" ('and ship captains') is added - almost as an afterthought - to the picture of the tobacco plant accompanied and a native smoking.2 Another example can be found in William Barclay's 1614 pro-tobacco treatise where he talks about the preeminence of American grown tobacco to that produced in the gardens of Europe. Barclay explains that the tobacco "brought home by Mariners and Traffiquers is to be used... [in England, for] the most fine, best, and purest is that which is brought to Europe in leaves... as the English Navigators first brought home."3

In an account written in 1545 of a voyage made in 1535-1536, French-Breton commodore Jacques Cartier notes that the natives of Canada smoked and took powder [snuff] and they "say that it keeps them healthy and warm"4. However, Cartier also explained that when they tried it, they had trouble with the smoke because it it was so hot. When French naval officer Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon took two ships to Rio de Janerio in 1555, Nicolas Barre, navigator for the voyage and one of the ship's captains, wrote letters to Paris giving accounts of the journey. In one of them, he said that the natives of Brazil could go without food for eight or nine days if they had tobacco.5

Writer Eugenio Courti says physician and botanist Nicholás Monardes "gives a long account of the wonderful virtues of tobacco as reported to him by the Spanish sailors”6 in the second part of his Historia medicinal de las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales que sirven al uso de la medicina, published in 1571. This book was based on reports Monardes had received from various people about the uses of various American plants and animals after he had published the first part of Historia medicinal in 1565.

Courti repeatedly gives credit to regular sailors for the spread of tobacco in the old world,

Artist: Reinier Nooms

Smoker Observing Shipbuilders In Italian Port,

From

"Shipbuilding at Porto

Santa Stefano" (mid 17th c.

)

although he does not usually specify period sources to back him up. Courti explains that the smoking habit was "common among the Spanish and Portuguese sailors in the various ports, was adopted by those of other nations in ever-increasing numbers, and the way was thus paved for its universal diffusion."7

As we have seen, the Spanish and Portuguese were the first explorers of the new world and it is likely that some of them acquired the habit while stationed there and brought it back with them. Courti goes on to explain that "the sailors, Spanish and Portuguese, and those Italians who had followed in Columbus's footsteps, were introducing the tobacco plant as well as the habit of smoking to the ports of Genoa, Naples, and, a little later, Venice"8 not long after they returned home. Spain's influence in Italy is not entirely surprising; Spanish viceroys ruled Naples from 1504 to 1707 and Sicily from 1516 to 1713. So the Italians would almost certainly have had contact with the Spanish sailors.

The simple sailor probably brought the custom of tobacco use to the old world long before it appeared in the annals of the more formal histories. Even Spanish physician and botanist Nicholás Monardes writing in 1571 "never was in America, but gathered his information from the lips of voyagers and adventurers, who returned from the newly discovered land to Sevilla."9 Courti further notes that tobacco would have been introduced by "Portuguese and English sailors to the ports of Genoa, Pisa, Spezia, and Venice; [and by] travellers from Germany and Switzerland to Lombardy."10

As for tobacco's informal entry into England, Courti says "we only know that it was brought from America by the sea-captains, who were the first to smoke publicly in the streets of London, to the great amazement of the people, who collected in crowds to see so strange and incomprehensible a sight."11 He further explains that it was first "looked upon as a curiosity, the custom becoming general only after the discovery of Virginia, when the British colonists returned home after a prolonged sojourn in that country."12

The Bear Garden, Bankside, London, From Visscher's Map

of London (1616)

As we have seen, Berthold Laufer says that Drake's 1572-3 exploration of the new world was likely responsible for first bringing the tobacco back to England (although he dismisses the role of the lowly sailors' importance in this process). Unfortunately, it is as difficult to follow the spread of tobacco through the common folks in England - those most likely to be impacted by the behavior of regular sailors - as it is to follow the introduction of the habit by sailors there.

In a footnote to his Exoticorum Libri Decem, Flemish botanist Charles d' Ecluse (Carolo Clusius) said that, beginning in 1585, the use of tobacco had taken such a hold of the English courtiers that they had begun importing ceramic pipes from Virginia to smoke tobacco.13 This was the same year Raleigh sent Sir Richard Grenville to establish a colony in Virginia and the year before Francis Drake brought them back in 1586. Yet they are sometimes credited with the introduction of the habit to England. Smoking apparently continued to spread after that. German lawyer Paul Hentzner in account of a trip to Southwark in 1598 that "the English are constantly smoaking tobacco" as witnessed at a bear garden (a public forum where bear baiting events were held).14

England took to pipe smoking in a way other nations could only admire and, in some cases, emulate. Laufer says,

, Adriaen Brouwer, 1630-8.jpeg)

Artist: Adriaen Brouwer - "De Roker" [The Smoker] (c. 1630-38)

"English sailors and soldiers, students and merchants carried the pipe victoriously wherever they went."15 Courti explains, "The bridge between England and the Continent was her near neighbour Holland... [smoking] was enthusiastically received in Holland, where it had been introduced by the sailors of both nations, and also by the English students who frequented the Dutch universities, especially that of Leyden."16

Writing in 1691, English physician Richard Carr explained that "Tobacco came into Use but some Years since, especially in England and Holland, chiefly amongst Soldiers and Seafaring People, perhaps from their too much Leisure from Business"17. While this doesn't positively pin down a date, it does give a sense of the ubiquity of the habit with a nod to those who encouraged it.

Courti says that in the low countries, tobacco "was widely cultivated as early as 1560, partly owing to the presence there of refugees from the religious persecutions in France. In the next few years a number of descriptions and illustrations of the plant came from the Press, especially in Antwerp"18. Beginning in the early 17th century, the Dutch Masters devoted parts of their images of peasants to smoking. (These images were not so much meant to portray the way of life among Dutch peasants during this period as they were to provide moral fables of dangerous habits that the artists' Calvinist clients could be tempted into adopting if they were not careful.19)

English sailors were even associated with tobacco by the Turkish navy according to Thomas Dallam's

Artist: Alain Manesson Mallet

The Dardanelles, From Description de l'Univers, Vol. 4, p. 149 (1683)

account. His company shipped an organ, a gift from Queen Elizabeth to Sultan Mohomad III, to Turkey in 1599 aboard the merchant ship Hector. When they were near the Dardanelles, Dallam says that the admiral of the Turkish fleet "sente a gallie unto us to demande his presente"20. The captain of the galley told the men on the ship that he couldn't go back to his admiral "excepte he carried him som smale presente."21 The gave him two Dutch chests, but the captain of the galley demanded and little something extra for himself. "Our Mr. [the ship's captain] answered that he had nothinge. Than he [the Turkish captain] desiered to have som tobacko and tobackco-pipes, the which in the end he had."22 Laufer explains, "It is generally asserted that tobacco was introduced into Turkey in 1605 under the reign of Sultan Akhmed I (1603-17)" and then points to this reference as evidence that "that tobacco and smoking, at least from hearsay, must have been known to the Osmans several years before that time"23. This provides an excellent example of how the formal history differs from the informal.

Once tobacco had conquered England and the Low Countries, it's spread in Europe owed a great deal to the Thirty Years War.

Artist: Jacob Duck - Guard House with soldiers and pack of cards (c. 1640-50)

As Courti notes, every major European power was involved in this war. "Germany was pre-eminently the theatre of war... Spanish soldiers occupied the banks of the Rhine; Lusatia and the Electorate of Saxony were full of the English mercenaries sent by James Stuart to the aid of his hard-pressed son-in-law, the ‘Winter-King’ of Bohemia. Both armies had long been inveterate smokers"24. In addition, there were smokers amongst the Dutch troops stationed in Germany at the time.

Some of the curious soldiers from the other armies who tried smoking took up the habit. Courti goes on to say that troops from Walloon (now Belgium), Bohemia (now in the Czech Republic) and Switzerland were all exposed to smoking during this war. He explains, "the soldiers of Gustavus Adolphus, on their return from the Thirty Years War [to Scandinavia], introduced the custom into the interior, while the seaports learned it from English and Dutch sailors."25 As Courti pointedly says, "war has always been the great encourager of smoking", primarily through transmission from one group of sailors and soldiers to another.26

Although some of the proponents of the formal history of smoking suggest their impact is irrelevant, sailors continued the spread the habit of smoking through the late 16th and early 17th centuries in a subtle, but not dismissable manner.

1 Count Eugenio Courti, A History of Smoking, Translated by Paul England, 1932, p. 51; 2 "Nicotiana inserta infundibulo ex quo hauriunt fumu Indi & naucleri", Matthias de l'Obel & Pierre Pena, Stirpium adversaria nova, 1570-1, p. 252; 3 William Barclay, Nepenthes, or The vertues of tabacco, 1614, not paginated; 4 "...puis mettent ung charbon de seu dessus, & sussent par l’autre bout, tant qu’ilz s’emplét le corps de fumée, tellement qu elle leur fort par la bouche, & par les nazilles, come par ung tuyau de cheminée: & disent que cela les tient sains & chauldement, & ne vont iamais sans avoir sesdictes choses. Nous avons esprovué ladicte fumée, apres laquelle avoir mis dedans nostre bouche, semble y avoir mis de la pouldre de poyure tàt est chaulde." Jacques Cartier, Bref Recit, 1545, p. 31; 5 Courti, p. 52; 6 Courti, p. 58; 7 Courti, p. 54; 8 Courti, p. 127; 9 Berthold Laufer, "The Introduction of Tobacco into Europe", Field Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology, Chicago, Leaflet Number 19, 1924, pp. 55-6; 10 Courti, p. 64; 11 Courti, p. 68; 12 Courti, p. 69; 13 Laufer, p. 34, cf. Footnote in Carolo Clusius, Exoticorum Libri Decem, 1605, p. 310; 14 Paul Hentzner, Hentzner’s Travels in England During the Reign of Queen Elizabeth, Translated by Horace, Late Earl of Orford, 1797, p. 30; 15 Laufer, p. 57; 16 Courti, p. 97; 17 Richard Carr, Dr. Carr’s Medicinal Epistles Upon Several Occasions, Translated from the Latin Epistolae medicinales: variis occasionibus conscriptae, by John Quincy, 1714, p. 15; 18 Courti, p. 61; 19 For more on this, see David Harley, "The Moral Symbolism of Tobacco in Dutch Genre Painting", Ashes to Ashes, Edited by S. Lock, L. A. Reynolds and E. M Tansey, 1998; 20 Thomas Dallam, Early Voyages in the Levant, 1893, p. 48; 21,22 Dallam, p. 49; 23 Laufer, p. 61; 24 Courti, p. 101; 25 Courti, p. 143; 26 Courti, p. 100

History of Tobacco in the 17th Century

Once tobacco had made its way from the new world to the old, much of its story moved from sea to land. At first smoking was viewed with curiosity as the sailors and new world explorers smoked the

Artist: John de Critz -

James I of England (1605)

plant in public. As it was increasingly adopted by the local populace in each region, however, some of those who chose not to adopt it began to object to the habit, primarily because of the smell.

The first public figure to strenuously object to tobacco smoke was King James I of England. He wrote a book denigrating the habit of smoking in 1604, calling it "so vile and stinking a custome"1. He goes on for pages in this manner, asking his readers why they would adopt "the barbarous and beastly maners of the wilde, godlesse, and slavish Indians, especially in so vile and stinking a custome?" He notes that the English "wallow in all sorts of idle lights, and soft delicacies, the first seedes of the subversion of all great Monarchies."2 He complains, "Our Cleargie are become negligent and lazie, our Nobilities, and Gentrie prodigall, and solde to their private delights, Our Lawyers covetous, our Common people prodigall and curious; and generally all sorts of people more carefull for their privat ends, then for their mother the Common-wealth."3

In an apparent effort to eliminate the habit in October of 1604, James raised the duty payable on tobacco to "the Somme of Six Shillinges and eighte Pence [or eighty pence] uppon everye Pound Waight thereof, over and above the Custome of Twoo Pence uppon the Pounde Waighte usuallye paide heretofore."4 This was unsupportable and was reduced a few years later, eventually settling at 24 pence per pound by 1615.5

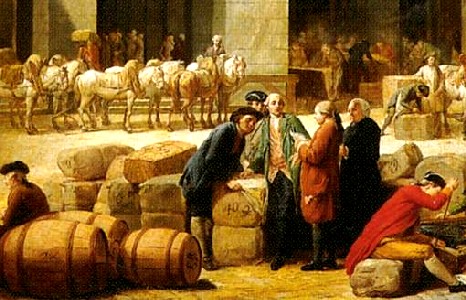

However, none of this stopped the consumption of tobacco by the English public. The outbreak of the plague in London in 1614 further

Artist: Nicolas-Bernard Lepicie -

The Courtyard of the Customs House (1775)

fueled the interest in tabacco as it was reported to ward off the illness.5 (This will be discussed in some detail later in this article.) And, as tobacco consumption increased, so did the taxes collected. Eventually King James had to allow that the habit raised significant moneys for his royal treasury and grudgingly allow smoking to continue in his realm. Such taxes proved to be such a dependable revenue source that they were continued with only minor modifications by James' successors through the golden age of piracy.6

The English relationship between tobacco and government was practically a template for most of the other European and some Asian governments. While interesting, the individual history of each areas' process from prohibition to taxation is beyond the scope of this article. Fortunately for those interested, author Eugenio Courti provides a fairly thorough and interesting history of how various other governments started out trying to regulate or eliminate tobacco smoking, only to eventually yield because of its ability to provide a dependable source of tax revenue.7 As Courti explains it, "Everywhere [in the mid and late 17th century] the policy of prohibition was giving way before the policy of taxation."8

1,2,3 King James I of England, A Counterblaste to Tobacco, 1604, not paginated; 4 King James, cited in Berthold Laufer, "The Introduction of Tobacco into Europe", Field Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology, Chicago, Leaflet Number 19, 1924, p. 30; 4 Jordan Goodman, “Webs of Dependence: Towards a Political History of Tobacco,” Ashes to Ashes: The History of Smoking and Health, 1998, p. 11; 5 Frederick William Fairhholt, Tobacco Its History and Associations, 1862, p. 88; 5 Note that this is an over- simplified explanation of the route taxation of tobacco took in England after James. A fuller explanation can be found in Jonathan Carver, A Treatise on the Culture of the Tobacco Plant, 1779, pp. 39-41; 7 See Chapter 7: The Governments' Surrender to Tobacco, Count Eugenio Courti, A History of Smoking, Translated by Paul England, 1932, pp. 149-86; 8 Courti, p. 161

History of Tobacco in the 17th Century - Sailors and Buccaneers

Men Smoking in a Tavern, Frontispiece From

Die truckene Trunkenheit, By Jakob Balde (1538)

As previous sections suggest, smoking appears to have been a popular habit among sailors. When at sea, they were free from the political intrigue that surrounded tobacco, having the potential to escape from the burden of taxation found in their home countries. Historian J.D. Davies points out, "The abundance of clay pipes brought up from the wrecks of seventeenth century warships suggests that smoking was one of the most popular activities aboard ship"1. Clearly, English navy sailors were freely indulging in tobacco during the seventeenth century.

England's navy was involved in a variety of wars during this time including the Dutch-Portuguese War (1602-61), the Anglo-Spanish War (1625-30), the three Anglo-Dutch Wars (1652-4, 1665-7 & 1672-4) and the Nine Years War (1688-97). When the English Navy was at war, a large number of sailors were needed to man their ships. Merchant sailors were often conscripted into service to help fill the ranks. As a result, both navy and merchant sailors would have been exposed to the habit during that service. Since pirates drew many of their men - some forced, some not - from the merchant service, one can see how the habit would have permeated the sailing community. While the Anglo-Dutch wars were being fought, two hospitals were established for the wounded - the Savoy Hospital and Ely House in London - where "beer was issued, as were clay pipes for men wishing to smoke"2, suggesting the prevalence of smoking among soldiers and sailors.

The buccaneers of the West Indies would certainly been exposed to tobacco by proximity, if nothing else. The plant was grown by the Portuguese in Brazil, by the English in Virginia and by the Spanish in Mexico. Tobacco had been planted in Cuba and the Dominican Republic in the 16th century. In his book about the buccaneers in the mid/late 17th century, Alexandre Olivier Exquemelin explains that in the Cayos of Cuba, "The inhabitants drive a great trade in tobacco, sugar, and hides".3 He goes on to explain that "huge quantities of [Cuban] tobacco... is sent to New Spain and Costa Rica, even as far as the South Sea

Artist: Richard Caton Woodville

William Dampier (1901)

[referring to South America], besides many ships laden with this commodity that are consigned to Spain and other parts of Europe, not only in the leaf but in rolls."4 (Tobacco leaves were often made into large rolls for transport and sale. This will be discussed later in this article.) Exquemelin also mentions that a great deal of tobacco was grown in Maracaibo, Venezuela, which was "well esteemed in Europe, and, for its goodness, is called there tobacco de sacerdotes, or priest's tobacco."5

Buccaneer William Dampier mentions that Bahia, Brazil exported 'Staple Commodities' of "Tobacco, either in Roll or Snuff, never in Leaf, that I know of" in European ships.6 He also said of a Spanish village he called Verina (located somewhere near modern Cumaná, Venezuela) that it was "famous for its Tobacco, reputed the best in the World"7. During his stay in Mindanao, Philippines, Dampier noted that the Dutch sailed there "in Sloops from Ternate and Tidore [two of the Maluku Islands of eastern Indonesia], and buy Rice, Bees-wax, and Tobacco: for here is a great deal of Tobacco grows on this Island, more than in any Island or Country in the East-Indies"8. As befits his curious nature, Dampier describes the tobacco grown there.

I do believe the Seeds were first brought hither from Manila by the Spaniards, and even thither, in all probability, from America: the difference between the Mindanao and Manila Tobacco is, that the Mindanao Tobacco is of a darker colour; and the leaf larger and grosser than the Manila Tobacco, being propagated or planted in a fatter soil. The Manila Tobacco is of a bright yellow colour, of an indifferent size, not strong, but pleasant to smoak.9

Tobacco had an important place among the buccaneers who were active in the mid/late 17th century in the Caribbean. Exquemelin's book mentions that on the island of Tortuga (Île de la Tortue, Haiti), in "the Middle Plantation... its soil is yet almost new, being only known to be good for tobacco."10 He elsewhere explains that tobacco

A Fanciful Image of a 17th Century Tobacco Plantation, From A School History of the United

States. from the Discovery of America to the Year 1878 (1878)

began being grown on Tortuga in 1598. "The first plantation was of tobacco, which grew to admiration, being likewise very good; but by reason of the smallness of the island they could plant but

little, there being many pieces of land there that were not fit to produce it."11 The island was settled by planters and hunters from Europe; the hunters supplied the planters with meat in trade for tobacco. When the buccaneer hunters found they could not make a good living hunting, they "began to seek out lands fit for culture, and in these they also planted tobacco."12 By 1644, Exquemelin says that those growing tobacco on the island "yielded a great quantity of very good tobacco, they selling yearly to the sum of twenty or thirty thousand rolls."13

Although smoking seems to have been fairly common among sailors during this period, the link between buccaneers and the habit of smoking is only to be mentioned in passing in the period books. For example, Dampier's explanation of the Mindanao tobacco suggests he smoked it, he doesn't otherwise discuss smoking in his book. Buccaneer surgeon Lionel Wafer provides quite a bit of detail on the way the Kuna natives smoked tobacco, mentioning that their plant "grows as the Tobacco in Virginia, but is not so strong", but doesn't directly state that he or other sailors smoke it.14 (He does, however, say that sailors kill pelicans so that they can use their beak pouches to store tobacco.15)

A Buccaneer, His Home, Boucain and Dog, From Histoire

des avanturiers flibustiers, Vol. 1 (1688)

While Exquemelin talks about all the places where tobacco is found in the Caribbean, he only mentions the habit among the buccaneers in a limited way. For example, he explains that due to the number and ferocity of the mosquitoes and flies in Hispaniola at night, the buccaneers "in their huts or cottages, ....constantly bum the leaves of tobacco, without which smoke they could not rest."16 With regard to tobacco smoking, he only says that as the buccaneers were sailing towards Panama in August of 1670 that "they had such scarcity of victuals, as the greatest part were forced to pass with only a pipe of tobacco, without any other refreshment."17 Still, the French edition of his book does show a woodcut of a 'typical' buccaneer who is smoking a pipe (seen at right).

Further proof of the buccaneers need for tobacco comes from Basil Ringrose's A South Sea Waggoner, where he notes that when the buccaneers under the command of Bartholomew Sharp were on Antigua in 1681, where they "sent a canoe ashore to get tobacco, and such other necessaries as we wanted"18. Linking tobacco and 'necessaries' is one of the strongest indications found among the buccaneer books. However, this seems to have been less a case of smoking not occurring than it being so common that it wasn't worth mentioning.

9 J.D. Davies, Pepys's Navy: Ships, Men and Warfare 1649-89, 2008, p. 156; 10 Kevin Brown, Poxed and Scurvied: The Story of Sickness and Health at Sea, 2011, p. 45; 11 Alexandre Exquemelin, The Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 66; 12 Exquemelin, p. 98; 13 Exquemelin, p. 71; 14 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703 p. 54; 15 Dampier, Vol III, 1703 p. 52; 16,17 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 333; 18 Exquemelin, p. 20; 19 Exquemelin, p. 41; 20 Exquemelin, p. 42; 21 Exquemelin, p. 46; 22 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America, 1903, p. 109; 23 Wafer, p. 123; 24 Exquemelin, p. 33; 25 Exquemelin, p. 141; 26 Exquemelin (quoting Ringrose), p. 313