Tobacco and Medicine Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Next>>

Tobacco and Medicine During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 12

The History of Tobacco and Health, continued

Tobacco & Health History – Debating Tobacco's Effectiveness as a Medicine (1601-1725)

"The consequence was that the use of tobacco, whether medicinally or for pleasure, soon began to meet with fierce opposition, particularly from those persons who had been confident of complete recovery after using it and were proportionately disappointed." (Count Eugenio Courti, A History of Smoking, Translated by Paul England, 1932, p. 106)

Not long after tobacco had been declared a panacea,

Work for Chimny-Sweepers Title Page, By Philaretes

(John Hammond) (1602)

physicians began to question its value as a medicine in a variety of cases based on their experience using it. The 1602 book Work for Chimny-Sweepers was written by 'Philaretes', almost certainly a pseudonym for English physician John Hammond1. The author made no bones about his opinion of tobacco. "And to be short neither one nor the other remedy can in any respect prevaile, if it be applied out of his due time and seasọn... And truely as no one kinde of diet can fit all sorts of bodies: So no one kinde of remedie can aptly be applied to all maladies, no more then one shooe can wel serve all mens feete."2 Hammond went on to list eight reasons tobacco shouldn't be used, only some of which are of interest medicinally. These include:

2. Tobacco's humoral qualities are too hot and dry than should be used daily.

3. It is a strong and violent purge [of humors, particularly phlegm].

4. It dries up moisture in the body.

5. It dissipates natural heat which produces 'infinit maladies'.

6. It contains venom or poison and "seemeth an enemie to the lyfe of man".3

He goes on to discuss each of these in detail later in his book which are discussed in the next section.

Grace Stewart says, "This book brought forth three [more books] in defence of tobacco, all published in London in 1602, and thus the stage was set for the London tobacco controversy that continued for about sixty-five years."4 Medical historian David Harley identifies

Tobacco Plant, From Hortus Eystettensis, By Basel Beslir (1613)

the three books that came out in defense of tobacco that year: one by the register of the College of Physicians, Roger Marbecke, another 'slight response' from an anonymous physician and a third which echoed Marbecke's called The Metamorphosis of Tobacco, "an anonymously published mock-heroic poem by a young Oxford-educated gentleman, John Beaumont."5

Of these three books, Marbecke's book is the only one of lasting medical interest. Harley explains that Marbecke "claimed to have been asked by friends to answer it when he published his anonymous reply, A Defence of Tobacco."6 Marbecke's book addresses each of Hammond's points, focusing as much on inconsistencies in the text as it does on presenting valid medical counter-arguments. In essence, he says:

2. Everyone's humoral makeup is different and the humors may change, so that he may use tobacco, "yet [the person may] retaine his naturall and perfect constitution still."6

3. Purging medicines are not in and of themselves bad, which is verified by the fact that many other purges are used daily in medicine.7

4. "[I]f [smoking tobacco] be well examined, it will be found a great helper, and maintainer, of that true natural good humiditie"8 as opposed to simply undesirably drying patients.

5. Sometimes the heat of tobacco is valuable, such as when it is used in naturally cold bodies.9

6. "This [notion that tobacco is a poison] is a matter of some importance indeed, and would be well looked unto"10. However, since God created plants to provide medicine11 and "poore Tabacco, is none of those dangerous poisons: unlesse you call him so".12

As has already been noted, King James I was no fan of tobacco. Berthold Laufer says John Hammond "is said to have been ordered or compelled to write this invective, presumably by James I"13, although he doesn't indicate his source for that idea. Harley points out that after Marbecke's death, "The previously obscure Hammond rose in the royal service... perhaps because the king respected his classical learning as well as his work on tobacco."14

Two years later, James I came out with his own scathing book on the problems from and dangers of smoking tobacco. Stewart argues that his book "was responsible for a large part of the controversy which followed."15 Much of what the book contains has little in the way of medical backing, but a few parts do suggest the author had some medical

Title Page, Counterblaste to Tobacco (1604)

knowledge or at least some help in presenting that information. In the book, James states that tobacco "hath a certaine venemous facultie joyned with the [humor-based] heate thereof, which makes it have an Antipathie against nature, as by the hatefull smell thereof doeth well appeare."16 James railed against the idea a medicinal panacea even existed, let alone that it could be tobacco.

And what greater absurditie can there bee, then to say that one cure shall serve for divers, nay, contrarious sortes of diseases? ...not only will a skilfull and warie Phisician bee carefull to use no cure but that which is fit for that sort of disease, but he wil also consider all other circumstances, and make the remedies sutable thereunto: as the temperature of the clime where the Patient is, the constitution of the Planets, the time of the Moone, the season of the yere, the age and complexion of the Patient, and the present state of his body, in strength or weaknesse.17

In some ways, this echoes Hammond's writing. It does show passing familiarity with the humoral concepts which most of medicine embraced at this time.

With regard to the multiple illnesses for which tobacco was said to be potent, James contended that "when a sicke man hath had his disease at the height, hee hath at that instant taken Tobacco, and afterward his disease taking the naturall course of declining, and consequently the patient of recovering his health, O then the Tobacco forsooth, was the worker of that miracle."18 Harley suggests that King James arguments against tobacco "sound as if he had derived his medical knowledge from Sir Thomas Elyot's Castel of Helth [1541] or discussed the subject with rather old-fashioned physicians"19. James regarded himself as a scholar with knowledge of philosophy and science, which may help explain some of the medical knowledge he included in his book.

In the fall of 1605,

Artist: David Loggan - Oxford Interior, Divinity School, From Oxonia Illustrata (1675)

expressed an interest in attending the regular debates on medicine and philosophy and taking part in the discussions following at Oxford University. Physicians Henry Ashworth and John Cheynell were appointed to conduct a discussion on a topic the Vice-Chancellor of the school felt the King would know about: tobacco. "Doctors and professors alike disputed hotly, for the King's benefit, about the nature and properties of the plant; the Court physicians joined in, while his Majesty listened with the liveliest interest to the discourse of the doctors"20, many of whom wisely chose to focus on the negative aspects of tobacco as a medicine. The King then gave his views on the topic, largely repeating the information found in his Counterblaste. When John Cheynell got up to speak, however, he held a lighted pipe and contradicted all the negative views of the previous presenters, "glorifying the uses and virtues of the magic plant, both in medicine and for smoking. …The doctor's speech for the opposition was so incisive and witty that the King and the rest of the audience laughed heartily; but of course the royal views prevailed in the end."21

Some authors who wrote during this period still touted the tobacco as panacea doctrine without getting involved in the debate. Botanist John Gerard trumpeted the fact that he spoke "by proofe; who have cured

Botanist John Gerard (1636)

of that infectious disease a great many, divers of which had covered of kept under the sickenesse by the helpe of Tabaco as they thought, yet in the end have been constrained to have unto such an hard knot, a crabbed wedge, or else utterly perished."22

However, Gerard was also clearly impacted by Monarde's earlier work. Gerard lists many of the same curative properties suggested by Monardes, adding some of his own experiences to affirm the use of tobacco. For example, he mentions the use of a cloth dipped in juice as well as a ball made of the leaves on toothaches, the ability to purge both upwards and downwards "as wee have learned of a friend by observation"23, the use of distilled tobacco juice in diziness, rheum of the eyes, migraines, in clearing vision, deafness, treating burns and scalds, among other things.24 He also explains, "I do make hereof an excellent Balme to cure deep wounds and punctures made by some narrow sharpe pointed weapon. Which Balsame doth bring up the flesh from the bottome verie speedily, and also heale simple cuts in the flesh ...not procuring matter or corruption to it, as is commonly seene in the healing of wounds."25

Not all medical authors held such strict views for or against tobacco during this period. Physician Edmund Gardiner pointed out in his 1610 book The Triall of Tobacco that other authors up

Artist: Louis Bernard Coclers (18th century)

until that point had "writ too partially of this plant, and not distinctly or plainely, as (I hope) in this small work I have done."26 He goes on to explain that his goal in writing is to show "the true use of it, and to remoove out of their [the tobacco user's] mindes, the errors that manie are possessed if not bewitched withall, and to bring both their mindes and bodies to a better temper and moderation: which thing as hitherto, for ought I know, hath not beene performed by any, nay scarcelie attempted."27

Gardiner presents problems with tobacco use as well as tobacco treatments he finds effective. He mentions "my good friend" Hammond's second point that tobacco is too hot and dry, yet also says that the plant "seemeth not so hot because it blistereth not, nor yet exceedingly heateth, and that deletery malignity which he adscribeth to it may be quintessentiall, although not elementarie."28 Suggestive of Marbecke's comment, he states, "it is a hard matter to finde any remedy that may doe absolute good, without some slight touch of harme, unlesse by art it be refined."29 Gardiner's book is generally supportive of tobacco, but only for use as a medicine. He includes recipes for a variety of compound medicines for specific treatments.

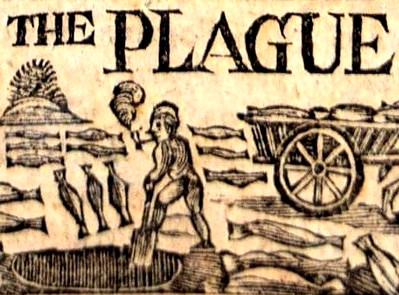

Even with the debate, the use of tobacco as medicine didn't disappeared during the latter half of the seventeenth century. The plague inspired several authors to recommend smoking as a deterrent to it. Dutch physician Isbrand van Diemerbroeck wrote about using tobacco to threat a 1635-7 outbreak of the plague in Nijmegan, Netherlands in his book, De peste libri. "The first [antidote] was tobacco where the smoke is drawn through a pipe in the mouth and then again released after a few retaining it: the value in this disease, both to myself and many others has been observed."30

Physician Thomas Willis wrote about the Great Plague in London in 1666, quoting Diemerbroeck as saying that tobacco was "not only a Preservative, but tells us, that himself,

Grave-digger Prophylactically Smoking, From The First Part of the Treatise of

the

Late Dreadful Plague in France, Title Page (1722)

when he was several times infected, by taking five or six Pipes of Tobacco together was presently cur'd."31 He notes that no tobacco shop owner was infected during the London outbreak. However, he finishes with the chide, "If 'tis not of so great virtue amongst us, the reason is because most Men have been accustomed to take it so excessively; wherefore it is grown so familiar to them, that it produceth no

alteration when it should be us'd as an Antidote."32

Antiquarian Frederick William Fairholt says that in the Great Plague of London, "tobacco was recommended and generally taken, as a preventive of infection. The physicians and those who attended the sick, took it very freely; those who went round with the dead-carts, had their pipes continually lighted. It was popularly reported, and as generally believed, that no tobacconists or their households were afflicted by the pestilence. This gave tobacco a new popularity"33.

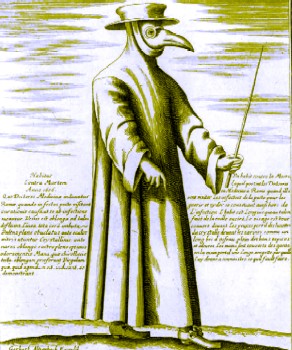

Artist: Gerhart Altzenbach - Plague Doctor (17th century)

Physician Willis recommended that travellers "should be furnished with something to smell to when they pass through infected Places."34 Samuel Pepys apparently agreed, explaining in the June 7, 1665 entry in his diary that while in the West End of London, he passed by "two or three houses marked with a red cross upon the doors, and “Lord have mercy upon us” writ there [signs indicating the inhabitants had the plague]... It put me into an ill conception of myself and my smell [breathing], so that I was forced to buy some roll-tobacco to smell to and chaw, which took away the apprehension."35

Of course, it wouldn't be right to discuss breathing herb-scented air during the plague during the 17th century without at least mentioning the infamous plague doctor costume (seen at left). "The most striking part of the costume of these plague doctors was the beak mask. The mask had two glass openings for the eyes and a long hollow mouth. In this hollow beak certain herbs (such as mint), dried flowers (roses) and other substances (ambergris, camphor, vinegar) were made, probably to prevent contamination with the plague and to reduce the stench."36 Since tobacco had a reputation for defeating the plague, it is quite possible (although not proven) that some plague doctors may have put tobacco into the beak.

Artist: David Teniers the Younger (att.)

A Boy Smoking (17th century)

Englishmen were not the only authors to comment on the English belief that tobacco was useful in preventing the plague. Frenchman Albert Jouvin de Rochefort wrote of his travels throughout Europe in 1672. He explained that while visiting a friend in Worcester, his friend

asked me if it was the custom in France as in England, that when the children went to school, they carried in their little bag with their books a pipe of tobacco, which their mother took care to fill early in the morning for their breakfast; and when it is time to take it, every one lays aside his book to light his pipe, the schoolmaster smoking with them, and teaching them how to hold their pipes and drink tobacco; thus accustoming them to it from their youth, believing it absolutely necessary for a man's health.37

This practice likely began with the Great Plague in London. Thomas Herne, writing his recollections, said, "I heard formerly [that] Tom Rogers, who was Yeoman Beadle, say, that when he was that year, when the plague rag'd, a School-boy at Eaton, [where] all the Boys at that School were oblig'd to smoak in the School every Morning, & that he was never whipp'd so much in his Life as he was one Morning for not smoaking."38

Even after the plague scare had died down somewhat, tobacco continued to be recommended as a medicine. Dutch physician Cornelius Bontekoe (née Dekker) wrote in 1685, "There is nothing so good, nothing so estimable, so profitable, and necessary for life and health as the smoke of tobacco, that royal plant that kings themselves are not ashamed to smoke."39

Cephalick and Opthalmick Tobacco Label (1722)

The 1722 book Of the Use of Tobacco, Coffee, Chocolate, Tea and Drams recites a typical list of tobacco cures of the sort created during the panacea-building period of the late 16th century. Admittedly, this book is essentially an advertisement given free to promote the specific blend of 'Cephalick and Opthalmick Tobacco', so it's medical provenance is easily questioned. However, it still shows that the public perception of the tobacco in relation to health could be played upon during that later years of the golden age of piracy.

1 David Harley, "The Beginnings of the Tobacco Controversy: Puritanism, James I, and the Royal Physicians", Bulletin of the HIstory of Medicine, Spring 1993, p. 38-9, Harley explains that the content of the book "clearly shows that they were written by [a] medical author", drawing on the initials J.H. found in the verse at the beginning of the work. "The only sustained medical criticism of tobacco previous to this book appears to have been a Cambridge thesis of 14 April 1597, entitled 'Inordinatus tabbaci usus lethalis,'...the thesis must have been written by John Hammond of Trinity College, who earned his M.D. degree in 1507. In 1602, Hammond appears to have been the only graduate physician with the initials 'J. H.' The similarities between the 1597 thesis and the 1602 book, and the signature under the verses, enable Hammond to be identified almost certainly as the author of the first published attack on tobacco."; 2,3 Philaretes (John Hammond), Work for Chimny Sweepers, 1602, not paginated; 4 Grace G Stewart, “A History of the Medicinal Use of Tobacco 1492-1860”, Medical History, July 1967, p. 239; 5 Harley, p. 39; 5 Roger Marbecke, A defence of tabacco, 1602, p. 16; 7 Marbecke, p. 28; 8 Marbecke, p. 31; 9 Marbecke, p. 38; 10 Marbecke, p. 43; 11 Marbecke, p. 44; 12 Marbecke, p. 48; 13 Berthold Laufer, "The Introduction of Tobacco into Europe", Field Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology, Chicago, Leaflet Number 19, 1924, p. 25; 14 Harley, p. 49; 15 Stewart, p. 239; 16,17,18 King James 1 of England, A Counterblaste to Tobacco, 1604, not paginated; 19 Harley, p. 44; 20 Count Eugenio Courti, A History of Smoking, Translated by Paul England, 1932, p. 85; 21 Courti, p. 86-7; 22,23 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed., 1636, p. 359; 24,25 Gerard, p. 360; 26 Edmund Gardiner, "The Epistle Dedicatorie", The Triall of Tobacco, 1610, not paginated; 25 Gardiner, "To the Curteous and friendly Readers", Triall, not paginated; 28,29 Gardiner, f. 4v; 30 "Primum erat tabacum (4) nempe illius fumus per tubulum seu fistulam ore attractus & post paucam retentionem inde rursus dimissus: cujus usum in hac peste tam in me ipso, quam in plurimis aliis igniter profuisse observavimus.", Isbrand van Diemerbroeck, De peste libri, Vol. 1, 1646, p. 127; 31 Thomas Willis, A plain and easie method for preserving (by God's blessing) those that are well from the infection of the plague, 1666, p. 21; 32 Willis, p. 21-2; 33 Frederick William Fairhholt, Tobacco Its History and Associations, 1862, p. 120; 34 Willis, p. 22; 35 Samuel Pepys, Pepys Diary, June 7, 1665; 36 Dr. Erwin JO Kompanje, "Plague doctors masks", erwinkompanje.wordpress.com, translated by the author, gathered 10/7/18; 37 Thomas Hearne, Remarks and Collections of Thomas Hearne, Volume 48,1906, p. 208; 38 "...demanda si c'eftoit la coustume en France, comme en Angleterre, quand les enfane alloient a l'escole de porter dans leur petit fac avec leurs livres, une pipe de tabac que leur mere a soin d'einplit de bon matin en place de leur dejeuner, pui qu'a l'heure de le prendre, chacun quitte son livre, pour allumer sa pipe, & le maistre d’ecole avec eux qui leur montre la maniere de tenir sa pipe & de boire le tabac; a quoy on les accoustume de jeunesse, tequ’ils croient estre absolument ·necessaire a la fante de l'homme.", Albert Jouvin de Rochefort, From Le Voyageur d’Europe, Tome III, 1672, p. 467; 39 "Maar niets is so goed, niets so seer te agten, niet so nodigen dienstig tot het leven en de gesondheid, als den rook van de tabak, dat Koninklijk gewas, dat Koningen selfs sig niet ontsien te roken.", Cornelis Bontekoe, Korte verhandeling van 's menschen leven, Vol. 1, 1685, p. 327; 40 Stewart, p. 242

Tobacco & Health History – Some Tobacco Health-Related Problems Identified (1601-1725)

During the debate about the healing properties of tobacco, the discussion coalesced around certain properties of the plant as well as how it was used. Although some of these were only discussed by a single author, several of them provided a platform for more widespread discussion.

The author who translated Dutch physician Giles Everard's text in 1659 offered a simple, practical consideration which he felt might affect the potency of the herb. "Experience teacheth us that our green Leaves will cure Wounds, Ulcers , and ether Diseases,

Photo: Alexander Kirk - Tobacco Air Drying in Cuba

sooner and mere certainly, than the dried Leaves brought from the Indies; It is credible that these dried Leaves coming so farre, have lost great part of their strength oft-times."1 Of course, as already explained in the section on preparing tobacco, the leaves used for smoking and snuff were dried before transport, so the distance traveled would have had little effect on the efficacy of those leaves. He appears to be suggesting that fresh tobacco leaves grown locally would have been preferable to those that were dried.

Two authors advised that while tobacco could help address certain health problems, it was not always a permanent cure, offering only temporary relief. English physician Edmund Gardiner explains that "leaves [of tobacco] doe palliate and ease for a time, but never performe any cure absolutely: for although they emptie the bodies of humours, yet the cause of the griefe cannot be so taken away."2 Botanist John Gerard repeats this assertion, adding, "That repletion [becoming full of something] doth require evacuation; that is to say, That fulnesse craveth emptinesse; and by evacuation doe assure themselves of health. But this [tobacco] doth not take away so much with it this day, but the next bringeth with it more."3

Three authors under study suggest that using tobacco for pleasure inured the user to its good properties and reduced its effectiveness as a medicine when it was required for healing. John Hammond (Philaretes) is a bit circumspect in this regard, stating that "sicke and diseased men... ought onely to use purging remedies

Artist: Adriaen Brouwer - The Smokers (mid 17th c.)

[such as tobacco] at such times as their bodies and humours shall be made fit and apt for the operatio[n] of the purge"4. He explains that in order for such purges to work, the humors to be purged must be made "fluxible [able to be purged], [so] that the parts and passages of the body being open, and the humours apt to runne, the purgation might worke with lesse torments and griefe to the partie purged."5

The other two authors present a more direct argument. John Gerard says, "Some use to drink it (as it is termed) for wantonnesse, or rather custome, and cannot forbeare it... which kinde of taking is unwholesome and very dangerous: although to take it seldom, and that physically, is to be tolerated, and may do some good"6. He goes on to suggest that ingesting the prepared syrup of tobacco would be better than drinking (smoking) it.

Everard cites the work of another doctor Pauvius (probably referring to Dutch botanist and anatomist Pieter Pauw), who was an "excellent Anatomist of his time, [and who] had once a subject for his Anatomical practice, whose smelling was quite lost, and there was not any thing left to be seen of the Processus Mammillares [olfactory bulb]: And this he conjectured, by good Arguments, to have happened by reason of the parties immoderate drinking of Tobacco."7

Just as the pro-panacea authors offered laundry lists of the health problems that could be cured by

Artist: Timothy Stansfeld Engleheart

Physician John Hammond, From National Galleries Scotland

tobacco use, John Hammond offered a variety of health problems which could be created by excessive tobacco use. These included violent vomits, excessive stools, gnawing and torment of the guts, coldness in the arms and legs, cramps, convulsions, cold sweats, pale skinne, lack of feeling, sense and understanding, loss of sight, giddiness and faintness. He makes the extraordinary statement, "what sperme or seed shall we expect to come fro[m] them that daily use or rather shamefully abuse this so apparent an enemy to the propagation... [is] both greatly altered and decayed by the use of Tobacco. Hereby ...the continuation & propagation of mankinde (consisting principally in his perfect & uncorrupt seed) is in these men much abridged."8 Hammond finishes his list by stating, "All which, or the most part of them concurring, do manifest a poisoned qualitie or venemous nature in the thing received."9

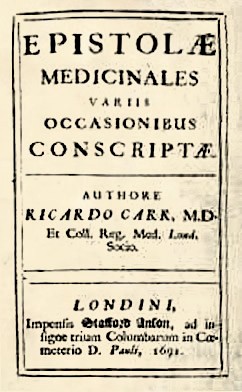

One of the health problems mentioned by Hammond is discussed by several other authors: stomach problems. Everard says, "this smoke doth vehemently move the stomack to nauseat, and to vomit, (as daily experience teacheth us) namely by cleaving to the inward parts, and so offending the peculiar juices contain'd in the stomack, and the Mesentary [a fold of the peritoneum], it destroyes their ordinary operations"10. Physician Richard Carr concurs, writing that "nothing can be worse for the Appetite, because it dilutes and enervates the Stomachichal Ferment, from whence cannot but arise an Iliad [several disastrous results] of Mischiefs."11 Hammond explained that while tobacco operates like other purges in emptying the stomach, "it seemeth to be of a far more thin & subtile nature then other purges bee, by meanes wherof, nature is so pricked and forced often times in such violent sort, as that it causeth violent evacuation, as well by stoole vomits and swetes, as also by salivacion, coughing & spittings, which thing other purges usually doe not"12.

Title Page for Richard Carr's Book (1691)

Richard Carr, whose epistles first appeared in print in 1691 in Latin and were translated into English in 1714, mentioned a couple of other health problems tobacco encouraged. "Experience informs us of many seized with apoplexy [unconciousness] in the Time of Smoaking"13. He also says that chewing tobacco is bad for the lungs, a connection most other physicians during this period do not make. "Chewing of this Herb, so familiar to some, is less to be allowed of, especially to hot Lungs, because it abounds with a very acrimonious Salt."14 He does not go so far as to state that smoking tobacco is bad for the lungs. Interestingly, King James does say that tobacco is "dangerous to the Lungs"15, although he neither supports this point with any evidence nor expands upon it. Carr also says that "continual Smoaking of it self will render the

Teeth, before Sound and White, as black as a Chimney, and at last rot them, insomuch, that there is scarce one in a thousand, who by long Smoaking does not lose only the Whiteness of Teeth, but the Teeth themselves."16 While he may have gone a bit overboard, smoking does stain the teeth yellow and cause gum decay.

One of the more curious illnesses alleged to be caused by tobacco was a black coating in the body, usually mentioned to be present in the brain. King James is probably the source of the idea, stating in his Counterblaste that tobacco smoke "makes a kitchin also oftentimes in the inward parts of men, soiling and infecting them, withan unctuous and oily kinde of Soote, as hath bene found in some great Tobacco takers, that after their death were opened."17 In a paper on the history of smokeless tobacco, the authors claim that during the 1605 debates at Oxford, "To everyone's horror and disgust, the King exhibited black brains and viscera, supposedly obtained from the dead bodies of inveterate smokers."18 However, no citation is given for this unlikely action, nor does it appear in the any other account of the debate found by your author.

With regard to tobacco blackening the internal organs, Giles Everard again cites anatomist Pauvius who apparently said that

Incorrectly Labeled Examples

of Healthy Lung versus

Smoker's Lung (COPD)

in his first Anatamical practices, digested a strong young man, and otherwise very sound, Whose brain was totally filled with black vapours like to soot. ...[the man] was so given to drink [smoke] Tobacco continually, that the pipe was seldom out of his mouth... Whereupon D. Pauvius did conjecture upon good grounds, that heap of soot and smoke contracted in the cavities of his brain by that means.19

Count Eugenio Courti explains

The question was taken so seriously that Adam Hahn, a doctor at Jena, felt compelled to add, in a new edition of a Tabacologia of 1667 which he published in 1690, a chapter of his own which gives a history of this quaint discussion, and elaborately proves that smoking does not encrust the brain with soot. The whole story was clearly made up by tobaccophobes to scare the public off their new habit.20

This tactic was used again in the 20th century to suggest that the tar in tobacco discolored the lungs as seen in the image shown at right. In fact, the lungs are not blackened by tar, although they can turn grey or black as a result of structural and functional abnormalities in the lung. The causes of this include chronic bronchitis - most commonly caused by cigarette smoking - and ephasima - which correlates with cigarette smoking, although it has not been proven to be caused by it. These diseases are grouped together under the umbrella term chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or smoker's lung. "A naked eye examination of a smoker's lung will usually reveal an enlarged gray-black lung with enlarged air spaces"21.

Two period authors also accuse smoking of causing death. Not surprisingly, Hammond said that the venomous nature of smoking resulted in some cases of excessive smoking leading to a "hastie and untimely death."22 The 17th century author who prefaced Giles Everard's book is a bit more expansive, explaining the lethal qualites in humoral terms. He says "that the smoak of Tobacco shortneth mens daies. For being that our native heat is like to a flame, which continually feeds up on natural moisture... it follows necessarily... life must needs fly away quickly, when the proper subject of life is dissipated and consumed: for with that moisture, the inbred heat fails also, and death succeeds."23 This refers to the idea that tobacco consumed excess humors (particularly phlegm), thus resulting in a lack of moisture in the body.

1 Giles Everard, Panacea, or the Universal Medicine, 1659, p. 25; 2 Edmund Gardiner, Triall of Tobacco, 1610, p. f.17v; 3 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed., 1636, p. 359; 4,5 Philaretes (John Hammond), Work for Chimny Sweepers, 1602, not paginated; 6 Gerard, p. 359; 7 Everard, p. 43-4; 8,9 Philaretes (John Hammond), not paginated; 10 Everard, p. 46; 11 Richard Carr, Dr. Carr’s Medicinal Epistles Upon Several Occasions, Translated from Latin by John Quincy, 1714, p. 17; 12 Philaretes (John Hammond), not paginated; 13 Carr, p. 18; 14 Carr, p. 19; 15 King James 1 of England, A Counterblaste to Tobacco, 1604, not paginated; 16 Carr, p. 20; 17 King James 1 of England, A Counterblaste to Tobacco, 1604, not paginated; 18 A. G. Christen et al, "Smokeless Tobacco", Journal of the American Dental Association, Nov. 1982, p. 825; 19 Everard, p. 44-5; 20 Count Eugenio Courti, A History of Smoking, Translated by Paul England, 1932, p. 174; 21 Michael Fishbein, M.D., "Smoker's Lung Pathology Photo Essay", medicine.net, gathered 10/7/18; 22 Philaretes (John Hammond), not paginated; 23 Everard, p. 52-3