Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Next>>

The Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory, Page 2

Medicine Theory

Much of the theory of medicine from this time-period could be traced back to the revered ancient

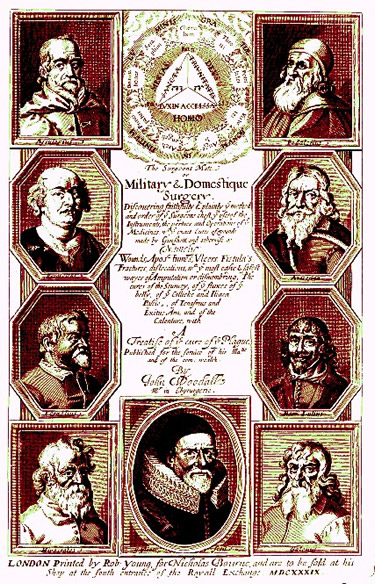

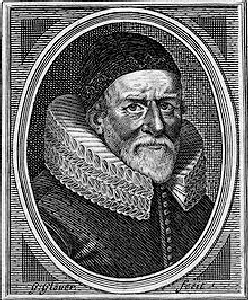

The Frontispiece From John Woodall's the surgions mate,

Featuring

(from top left) The Greek God Asculapius, Aescapulus' Son Podalirius,

Paracelsus, Arabic Physician Avicenna. French Physician Jean Fernel

(Fernelius), Majorcan Ramon Lull (Lullius), Hippocrates, Woodall

and Galen (1639) writers such as Hippocrates, Celsus and Galen. Galen's work on medicinal remedies and humor theory are found in nearly every popular medical book from the time.

However, a number of physicians began proposing alternative theories on the way medicines and the body worked and what sorts of medicines were most appropriate for patients. While traditional physicians relied on Galen's natural remedies and the theory of humors to guide them, more progressive physicians adopted some of the modified 'chemical' remedies and alternative theory of how the body worked proposed by Paracelsus in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Historian Norman Gevitz explains,

...Galen (129-c.216) [believed] that disease represented and imbalance among the four humors: phlegm, blood, black bile, and yellow bile. Humors and illnesses were classified by the primary qualities of hot and cold and the secondary qualities of dry and moist. Drugs with opposite properties were chosen as appropriate correctives to the underlying humoral imbalances....Paracelsus (1493-1541) dispensed with the idea of humoral pathology, conceiving of the body as a grand chemical laboratory. He postulated that disease was the result of chemical disturbances, possibly the result of a malfunction in a given organ. In preparing drugs, Paracelsus argued for 'pure' remedies that could be sublimed [vaporized so purified solids when cooled], distilled, and resolved [separated] from crude materials, and gave special emphasis to the therapeutic benefits of metals and minerals.1

Both Galen's natural and Paracelsus' chemical medical theories came to affect the medicines recommended by the sea surgeons of the golden age of piracy, so let's look at them a little closer.

1 Norman Gevitz, "'Pray Let the Medicines Be Good': The New England Apothecary in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries", Apothecaries and the Drug Trade, editors Gregory J. Higby & Elaine C. Stroud, p. 12

Medicine Theory: Galen's Humors

Artist: Ferdinand Georg Waldmuller

Galen, Taken From

Apothekenladenschilder 4 (1826)

From his writings in the second century A.D., Greek physician Galen of Pergamon's theory of medicine explained that there were four humors in the body and health was maintained by both keeping them in balance and not allowing them to be corrupted. (According to physician Robert James, humors could be corrupted "from the Commixture of heterogeneous Aliments [nourishing foods], the Bile, and fermenting saliva Humours, which stagnating in the Stomach and Intestines, especially the Duodenum, become corrupted by their Continuance there"1. Basically, they mix together and sit for too long.) Galen's theories continued to hold sway in medicine for nearly two millennia, still being widely discussed in and disseminated by medical books written during the golden age of piracy.

According to Galen's theory, plants had four primary or first qualities: hot, cold, dry and wet (or moist). French physician Jean de Renou explains that these were the 'simple qualities' or first qualities of medicinal plants. He notes that these qualities could be compounded in specific ways, creating more complex qualities, including: "hot and moist, hot and dry, cold and moist, cold and dry"2.

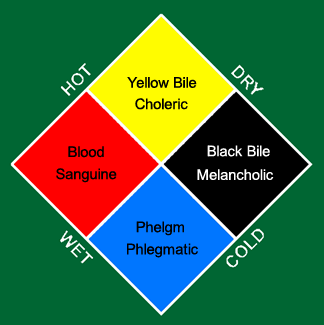

The Chart of Humors, Temperaments & Their Qualities

Renou goes on to reveal that certain medicinal qualities were preferable to other qualities, for "in simple Temperatures [referring to the four simple qualities] hot Medicaments are better than cold, and moyst than dry; in compounds, hot and moyst are most wholesome, cold and dry most dangerous."3

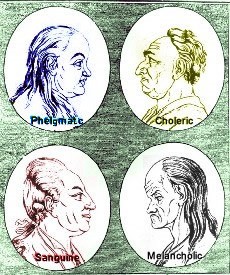

If that isn't complicated enough, Renou notes that the medicine's usefulness to a patient depends on how closely it matches the patient's temperament. There were four temperaments which appeared when the patient's humoral makeup favored one humor over the others. The four temperaments were: Sanguine, Choleric, Melancholic and Phlegmatic. (See the chart at right and the figure below.) Renou explains that when a medicine's qualities are "nearer mans temper[ament], by so much it is more wholsome [to them]; and by how much it is more remote,

Artist: J. C. Lavaters

The Four Temperaments, From

Physiognomische Fagmente (1792)

by so much more [is it] malignant [to the patient]."4

This explanation is somewhat confusing, so let's look at a practical example. Referring to the chart: A phlegmatic patient would respond well to wet and cold medicines (which are near to his [blue] quadrant, and thus to his temperament). He would react poorly to hot and dry medicines (which are opposite to his quadrant/temperament). The same was felt to hold true for all the different patient temperaments.

The basic four qualities (hot, dry, wet and cold) were further broken down into four degrees of potency. Modern author Andrew Wear provides a brief explanation of how these four qualities worked:

The qualities were grading on a scale of one to three or four, with qualities of the first degree acting gently and imperceptibly and those of the third degree violently and vehemently: the fourth degree represented perfect heat or cold, etc., and would not be found in a body composed of a mixture of qualities such as a herb. [Here he is referring to Renou's concept of usefulness of medicines to the patient's temperament.] This scheme meant that all remedies would have some power to act upon the body and that the appropriate medicine could be used against the corresponding qualitative intensity of the patient's illness.5

Some of the period physicians give further insight into the four qualities, although these tend to be a bit more esoteric than Wear. English physician Thomas Brugis explains: "The first degree doth alter and change somewhat obscurely, The second manifestly, The third with great efficacy and vehement labour, The fourth excessively alters and expels sense by its violence."6 Renou gives a slightly different explanation, although it is along the same lines. He says that when a humoral quality of a medicine acts obscurely in the first degree, apparently in the second degree, vehemently in the third degree and perfectly in the fourth degree.7

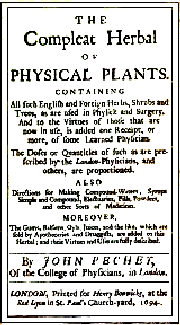

With this in mind, many of the pharmacopoeias and dispensatories of the time reported a medicine's qualities and degrees8, although this was somewhat hit-and-miss. For example, John Pechey's 1707 book The Complete Herbal of Physical Plants divides the subject into native and foreign plants. He usually gives some indication of the primary qualities of foreign plants without mentioning their degrees, but only occasionally provides the same information for native plants. This may be because he "thought it needless to trouble the Reader with the Description of those that every Woman knows, or keeps in her garden."9

Not everyone subscribed to the idea. Physician Robert James reported that grading medicines "according to their several Degrees, seems to bear an Air of Absurdity in it, since these Degrees cannot be absolutely determined, but are meerly relative to the several Constitutions to whom such Medicines happen to be exhibited."10

The concept does seem to lack rigorous backing. Pharmacy historian Leslie Matthews reports that Anthony Askham, author of the 1550 book Herball of the properties of Herbes, derived most of the material in his book from Richard Banckes' 1525 Herball, matching the primary qualities defined by Banckes, but somewhat randomly changing the degrees. As Matthews explains, "[I]f Banckes wrote '2nd [degree for a medicine], Askham is sure to write '3rd', or vice versa."11

Even so, the concept of degrees of a medicine's primary qualities was generally accepted and reported in many pharmacopoeias and dispensatories. They will be included in our Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory when they can be found in the period pharmacopoeias, dispensatories and herbals.

There were other qualities of medicines to consider. Drawing upon Galen, Renou defines a variety of "second qualities"

Physician and Author Jean (Joannes) de Renou of medicines which were less esoteric. "The second qualities are concomitants [followers] of the first, Elementary or simples [simple medicines - those not combined or altered], by whose help it is that they exist and manifest their virtues"12. While this sounds complicated, it really wasn't.

The 'second qualities' consisted of the physical aspects of the medicines. For example, Renou states that, "the soft [plant to be made into a medicine] is to be preferred before the hard, and the smooth before the sharp or rough"13. He also advises the reader to choose sweet-smelling medicines over those with "An ill and stinking smell" since that "aggravates the head, vexes the heart, subverts the ventricle, infects the spirits, moves a loathing, causes grievous and laborious purgings, and oftentimes vomiting."14 (Put that way, he does have a point.) Such 'second qualities' are sometimes mentioned in pharmacopoeias, dispensatories and herbals, although not nearly as often as the primary qualities.

He also identifies a third quality of medicine, which he calls the occult, mostly because the physicians of this time did not understand how or why some medicines worked. As Renou explains, "some properties can neither be known nor explained; for no man can bring any firm and invincible argument or reason, why those Spanish flyes, or Cantharides, should vex the bladder with an inflammation, or hot disposition, being applied far from it, or why the ashes of Crabs, being of a drying nature, should have such an admirable property against the biting of mad Dogs"15. Unable to explain this aspect, Renou simply advises that for such a medicine, "no certain account can be rendred of it, nor yet any exact knowledge thereof be apprehended, but [it] is known onely by experience."16

Although Renou goes on at length about the occult aspect of medicines, they are rarely mentioned in the other period medicine book.

1 Robert James, Pharmacopœia universalis, p. 136; 2 Jean de Renou, A Medicinal Dispensatory, p. 33; 3,4 de Renou, p. 35; 5 Andrew Wear, Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680, p. 88;6 Thomas Brugis, The Marrow of Physick, 1669, p. 2; 7 de Renou, p. 11; 8 For examples, see the listing of simple medicines in de Renou's A Medicinal Dispensatory (1657) and Nicholas Culpeper's , Pharmacopoeia Londinensis, (1720), John Pechey's The Compleat Herbal of Phyiscal Plants (1707) and John Quincy's Pharmacopoeia Officinalis & Extemporanea (1719); 9 John Pechey, The Compleat Herbal of Phyiscal Plants, Introduction, p. 3; 10 James, p. 177; 11 L.G. Matthews, "Herbals and Formularies", From The Evolution of Pharmacy in Britain, Edited by F.N.L. Poynter, 1965, p. 197-8; 12 de Renou, p. 11; 13,14 de Renou, p. 36; 15,16 de Renou, p. 12

Medicine Theory: Paracelsus' Chemicals

Paracelsus - Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von

Hohenheim,

From the Wellcome Museum (1455)

Paracelsus challenged the traditional medical view of bodily humors set forth by Galen and furthered by the 10th century Persian physician Avicenna (Ibn Sīnā).1

His actual name was Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim. Around the time he received his doctorate degree, he began using the name "para-Celsus" to indicate that he was above or beyond renowned 1st-century Roman medical writer Aulus Cornelius Celsus.2

Paracelsus "assured his students he did not 'beggarly collect out of Hippocrates and Galenos [Galen],' but had taken 'from the best possible teacher, to wit, from my own experience and experimentation."3 He publicly rejected humorism (actually burning Galen's books on the steps of the University of Basel in Switzerland in 15274), declaring that 'there will be no reference to complexions and humors which... have widely prohibited the understanding of them, their origins and their critical course.'"5

Yet his theory was based on a very similar concept. He appears to have modified the four humors into the 'tria prima' or three primary principles: "sulphur, mercury and salt"6. Although these three things sound familiar, the words did not refer to the elements we normally associate with them. Instead they indicate the elements in the body that were capable of causing illness. They included "a combustable element (sulphur) a fluid and changeable element (mercury) and a solid, permanent element (salt.)"7

Paracelsus felt that disease was caused "by a local separation of one of these three principles from the other two"8 and the symptoms and cure depended on which of the three elements caused the illness.9 Although the details are different, much of his theory is remarkably similar to Galen's concept of humors.

The Cagey Sea-Surgeon, John Woodall

Interestingly, some of Paracelsus' theory made its way to sea. Sea surgeon John Woodall treats his readers to a breakdown of the Paracelsan idea in his "A Treatise of Salt in generall"10 . While Woodall generally preaches humorism elsewhere in his book, he here identifies three salts and ties them into Paracelsus' scheme: "...each of [the three kinds of salts - animal, vegetable and mineral] which have a three-fold severall substance contained in them, viz: A volatile salt, a fixed salt, and a Caput mortuum ['dead head'] named also Terra Damnata ['condemned land'], otherwise it may be tearmed to containe Flegme, a spirit, an oyle, which againe is called Sal, Sulphur, and Mercury [Paracelsus' three elements], each dividable, plainly, and easily by Art".11

It is curious how Woodall blithely mentions the humor phlegm and Paracelsus' three elements salt, sulphur and mercury in the same statement. He concludes his special section on such medicines by sort of side-stepping controversy, explaining that "Many learned writers have through their whole volumes, left to future ages as a trueth ratified, that next the Almighty hand which createth all things, Sal, Sulphur, and Mercury are the three principles whereof every naturall body is composed"12.

Artist: Philippe Galle after Jan van der Straet

'Distillatio' - Medical Preparation of Elixirs From Metal Amalgamations

From the Wellcome Museum (late 16th/early 17th century)

His approach to medicines also deviated from Galen's more natural remedies. Paracelsus devised "the concept of the body as a chemical laboratory. As a result of advocacy by Paracelsus and his followers, the internal use of chemical remedies (mineral salts and acids, and substances prepared by chemical processes such as distillation and extraction), which had occurred sporadically before him, was made a matter of principle and study. He coined the famous phrase that 'it is not the task of alchemy to make gold, to make silver, but to prepare medicines.'"13

As pharmacy historian Leslie Matthews explains, his doctrines "caused physicians to think deeply about the advantages of using the new chemical remedies, and the enthusiasm of his followers kept this subject to the fore."14 Edward Kremers and George Urdang agree, noting how, through his influence, pharmacy was transformed "from a profession based primarily on botanic science to one based on chemical science."15

1 Kremers and Urdang’s History of Pharmacy, 4th ed., Edited by Glenn Sonnedecker, p. 40; 2 "Paracelsus", Encyclopedia Britannica, gathered from the internet 4/7/15; 3 Kremers and Urdang, p. 41; 4 "Paracelsus: Career at Basel", Encyclopedia Britannica, gathered from the internet 4/7/15; 5,6 Kremer’s and Urdang, p. 41; 7 "Paracelsus: Philosophy," wikipedia.com, gathered 4/7/15; 8 Kremers and Urdang, p. 41; 9 "Paracelsus: Philosophy," wikipedia.com, gathered 4/7/15; 10 See John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 250-256 (Note: page 251 has been mistakenly labeled 271, a page scheme which carries through the rest of the book); 11 Woodall, p. 271 (251); 12 Woodall, p. 306; 13 Kremer’s and Urdang, p. 40; 14 L.G. Matthews, "Herbals and Formularies", From The Evolution of Pharmacy in Britain, Edited by F.N.L. Poynter, 1965, p. 208-9; 15 Kremer’s and Urdang, p. 43

Medicine Theory: The Golden Age of Piracy

Jan Baptist Van Helmont

In the mid-17th century, Jan Baptist van Helmont refined Paracelsus' 16th century ideas, suggesting that diseases lodged in organs of the body. With this in mind, he rejected humorism and also embraced chemical remedies.1 However, he did not rely exclusively on chemically prepared medicines and, like Galen, "believed that simples were God-given, and ...tried to improve them."2

When viewed strictly, the Galenist and Paracelsian theories appear to be in opposition to each other regarding the type of medicines employed. Yet most medical practitioners during the 17th and 18th centuries "appear to have gone about their business employing remedies from whichever tradition seemed to produce the best results."3

One of Van Helmont's statements explains the practical philosophy of how medicines were used during this time period quite well, "Physitians at this day, do not despise Chimical remedies, the which, their books do lately testifie."4 As the physicians shown on the frontispiece of John Woodall's book the surgions mate at the beginning of this section show, both medicinal theories and their founders were embraced to some degree.

1 Allen G. Debus, Chemistry and Medical Debate: Van Helmont to Boerhaave, 2001, p. 43-4; 2 Andrew Wear, Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680, p. 100; 3 Norman Gevitz, "'Pray Let the Medicines Be Good': The New England Apothecary in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries", Apothecaries and the Drug Trade, editors Gregory J. Higby & Elaine C. Stroud, p. 12; 4 Debus, p. 44