Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Next>>

The Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory, Page 7

Obtaining Medicines: The Traveling Surgeon - Going Native

There are a couple of accounts where the sailors

Alexander Selkirk Dancing With His Animals, From A Universal Collection

of Authentic and Entertaining Voyages and Travels, p. 86 (opp) (1765)

(and one buccaneer surgeon) tried local remedies recommended by the natives. In most of these cases the cures were tried because the men involved were stranded and had no other recourse.

The famous stranded Scottish sailor Alexander Selkirk, who lived alone on Juan Fernandez Island for over four years, was forced to use whatever he found there. (His tale, told in Woodes Rogers' book, was almost certainly the inspiration for Defoe's book Robinson Crusoe, for whom the island is named today.) Rogers found Selkirk when they stopped on Juan Fernandez in 1709. Among other thing Selkirk ate while stranded, Rogers reported that he "found there also a black Pepper call'd Malagita [Malagueta – a chili pepper], which was very good to expel Wind, and against the Griping [pain] of the guts."1

Buccaneer surgeon Lionel Wafer was stranded with the Kuna Indians in the Isthmus of Darien [Panama] because he was unable to keep up with his crew hiking across the Isthmus after burning his knee. The Kuna "undertook to cure me; and apply'd to my Knee some Herbs, which they first chew'd in their Mouths to the consistency of a Paste, and putting it on a Plantain-Leaf, laid it upon the Sore. This prov'd so effectual, that in about 20 Days use of this Poultess, which they applied fresh every Day, I was perfectly cured".2

He gives a rollicking account of his adventures during the time he spent with the Kuna.

A Calabash (Lagenaria siceraria) or Bottle Gourd

Among the medicinal plants he mentions are the calabash - Lagenaria siceraria. He says, "The bitter sort is not eatable, but is very Medicinal. They are good in Tertian’s [malarian fever which returns every second day]; and a Decoction of them in a Clyster [enema] is an admirable Specifick in the Tortions [pains] of the Guts or dry Gripes [pain in the bowels]."3

He reports on another gourd which he says "grow creeping along the Ground, or climbing up Trees in great quantities, like Pompions [pumpkins] or Vines. Of these also there are two Sorts, a Sweet and a Bitter: The Sweet eatable, but not desirable: the Bitter medicinal in the Passio Iliaca [intestinal blockage], Tertian’s, Costiveness [constipation] &c. taken in a Clyster."4

Wafer also discusses the medicinal use of "a sort of Insect like a Snail... which is call’d the Soldier-Insect"5 which is probably a Caribbean hermit crab.

The Oil of these Insects is a most Soveraign Remedy for any Sprain or Contusion. I have found it so, as many others have done frequently: The Indians use it that way very successfully, and many of the Privateers in the West-Indies: And our Men sought them as much for the Oil, as for the sake of eating them. The Oil is of a yellow Colour, like Wax, but of the Consistency of Palm-Oil.6

in one case, a local cure was not used only of necessity; rather it was tried because nothing else seemed to work. William Damper mentions a man 'always troubled with sore Legs' who "had his first Knowledge of them in the Isthmus of Darien, he having his Receipt [recipe for the medicine] from one of the Indians there"7.

Dampier describes the plant the man used as a "Vine that supported it self by clinging about other Trees. The Leaves reach six or seven Foot high, but the Strings or Branches 11 or 12. It had a very green Leaf, pretty broad and roundish, and of a thick Substance."8 The preparation was fairly simple: "These Leaves pounded small and boiled with Hog’s Lard, make an excellent Salve. Our Men knowing the Virtues of it, stockt themselves here: There were scarce a man in the Ship but got a Pound or two of it; especially such as were troubled with old Ulcers, who found great Benefit by it."9

1 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 127; 2 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of Darien, p. 38-9; 3 Wafer, p. 102; 4 Wafer, p. 103; 5 Wafer, p. 114; 6 Wafer, p. 115; 7 William Dampier, Memoirs of a Buccaneer, Dampier’s New Voyage Round the World -1697-, p. 302; 8 Dampier, 302-3; 9 Dampier, p. 303

Keeping Medicines Viable at Sea

"To ensure preservation for as long as possible, care was needed in corking, especially when fermentation might take place, as in syrups, which must have their 'covers tyed hard down and pricked'. Other preparations had to be stirred at intervals; those that grew dry must have honey or sugar

Artist: Joseph Nicholls

Loading Captain Teach's Ship, From The General

History of the Pyrates, Following p. 202 (1736)

added, or some rectified spirits poured on; the rhubarb must be examined to see 'that Worm hath not got into it (as it will certainly do at four years old) and let it be wrapt up in Cotton, and kept dry'." (John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy, Volume 2, p. 158)

Some of the period physicians and apothecaries discussed how long medicines remained viable as well as ways they could be kept viable. This would have been of particular interest to sea surgeons who primarily had to rely on their stores to see them through a voyage. Factors such as how a plant was made into a medicine, they way to properly store them to maintain the medicines and how long they could be expected to last were important to the duration of a medicine's potency.

While some supplies could be procured and refreshed in foreign ports, others could not. Plants in particular had to be selected with an eye to how long they would last. "Woodall himself admitted the difficulty of keeping herbs viable, listing fourteen herbs and roots – rosemary, mint, clover, sage., thyme, absinthe, blessed thistle, melissa (balm mint) Sabina, (juniper), althea (hollyhock), Raphana silvestris (horseradish), pellitory (pyrethrum, angelica, and comfrey – as 'herbes most fit to be carried."1

Woodall advised surgeon's mates (or assistants) "to keepe a Jornall in writing of the daily passages of the voyage... [which, among other facets of the medicines, included information on] what medicines keepe their force longest, & what perish soonest."2 By keeping track of this and other factors such as what worked best where and in what doses, "he may do good service to God, his

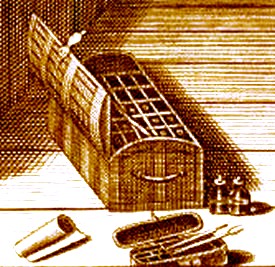

A Medicine Chest and Pocket Kit, From The Infallible

Montebank

or Quack Doctor, The British Museum (1690)

Countrey, and himselfe, and the benefit will be his, namely Gods favour, preferment and a good reputation in the world will bee gained therby, which will bring abundance of good things with it, which God grant for his mercy sake."3 This suggests that the durability of medicines on long sea voyages may not have been well understood when he wrote the book.

Woodall gives some advice on which medicines were best for voyages and which weren't. When discussing Auria Alexandrina [an opiate], he explains that "the cause why I have not appointed this good composition, nor any of the three last mentioned Philontums [Philonium Romanum, Philonium Persicum and Philonium Tarsense] to the Surgeons Chest, though I know them to be good medicines, is because they will not keepe an East India voyage, and Laudanum opiate paracelsi is sufficient for ought the other can doe. Wherefore I rest satisfied therewith."4 In his description of 'the white Causticke' (most likely a form of Lixivium), he noted that it "may well be carried in the Chest, for that it will last well an East India Voyage"5.

While interesting and potentially helpful, such comments were not the norm in his book. Since he gives the most detailed description of medicines in any of the sea surgeon's books from this time period, the surgeon had to find advice elsewhere on what medicines worked best for their voyage.

1 Joan Druett, Rough Medicine: Surgeons at Sea in the Age of Sail, p. 52-3; 2 John Woodall, "The Office and Duty of the Surgions Mate", the surgions mate, 1617, p. 3; 3 Woodall, "The Office and Duty of the Surgions Mate", p. 4; 4 Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 88; 5 Woodall, p. 67

Keeping Medicines Viable at Sea - Medicine Types

Fortunately, physician and herbalist Nicholas Culpeper included a variety of comments on how long different types of medicines lasted and how they should be stored in his 1666 book The English Physitian. He divides the medicines by type of medicine (which is the same way the compounds in his book A Pharmacopoeia Londeniis are divided); each type is to be kept and sealed in a particular way. How long they will last is in part dependent upon what type of preparation they are. Culpeper provides useful information on keeping medicines for Distilled Waters, Syrups, Juleps, Decoctions, Oils, Electuaries, Conserves, Preserves, Robs, Ointments, Plasters, Poultices and Troches. We will look at each in turn.

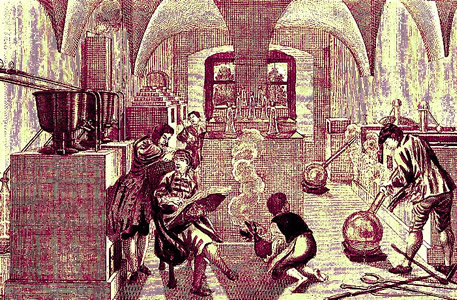

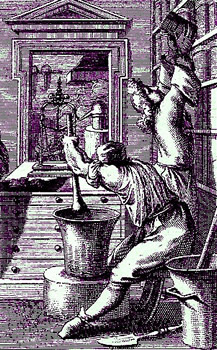

Artist: Martin Engelbrecht

Interior of a Distilling Laboratory,

From the Wellcome Collection (1720)

For distilled waters, Culpeper advises that herbs and flowers used should be "distilled when they are in their greatest vigor"1. He warns that using corks or paper to close the top of distilled water containers "makes them musty" so he tells his readers "your best way then is to stop them with a Bladder, being first wet in water, and bound over the top of the Glass."2 He also says that those distilled using a pewter still will keep for a year if properly sealed, those distilled in Sand Furnaces "are twice as strong; so will they endure twice as long."3

With syrups, he explains that they can be made by infusion (soaking the plant), decoction (heating or boiling to concentrate a plant's essence) or from juices. Culpeper notes that juices are the 'best made'.4 It is advisable to place syrups "in Glasses or stone Pots, and stop them not with Cork nor Bladder, unless you would have the Glass break, and the Syrup lost; ...only bind a paper about the mouth."5 Properly made syrups "will continue a year with some advantage: yet of of all, such as are made by Infusions keep the least while.”6

Artist: Robert A. Thom

A Variety of Containers, From The Marshall Apothecary

Culpeper notes that juleps (sweet flavored drinks) "are made for present use, and therefore it is in vain to speak of their duration."7

Culpeper explains that decoctions are like syrups, except "Syrups are made to keep, Decoctions only for present use: for you can hardly keep a Decoction a week any time, if the weather be hot, not half so long."8 He does explain, "Decoctions made with Wine, last longer than such as are made with water... your best way it to make it with white Wine instead of water, because this is most penetrating."9 He suggests that when they are not for immediate use, the practitioner should "Keep all Decoctions in a Glass close stopped, and in the cooler place you keep them, the longer they will last ere they be sour.”10

Oils can be either simple or compound medicines. Simple oils are made from squeezing seeds or fruit while compound oils are made with simples such as herbs, flowers and roots combined with olive oil. They are to be kept "in a stone or glass Vessel for your use."11 He does not say how long oils will last, although modern wisdom advises that non-refrigerated vegetable oils tend to be good for about 6 months to a year.12

Electuaries (pastes) are also to be made as needed, although Culpeper here points out that "it is requisite that you keep always herbs, Roots, Seeds, Flowers, &c. ready"13. He recommends keeping "them whole than beaten: for being beaten they are the more subject to lose their strength, because the Air soon penetrates them."14 They are to be stored "in a pot"15.

Photo: McKarri - Orlop Deck of the Replica of the Amsterdam, Lost in 1749

Keeping the raw materials required for things to be ready made such as electuaries, juleps and decoctions presented a particular problem for sea surgeons. Unlike their land-based counterparts, they had to have everything with them, preferably in their medicine chest. They had to be kept so that the contents wouldn't be damaged by the constant damp found on lower decks - the orlop deck or the cable tier where the surgeon's materials would be stored. Sea surgeon John Moyle mentions that 'dry things... are done up in Papers... [and] decently stowed" in the instrument chest.16 The instrument chest was separate from the medicine chest, being so called because it was originally meant for stowing the surgeon's operating tools and instruments. Moyle notes that "in that [instrument] Chest there is nothing but what is dry. Here you may keep your dryed

Herbs, Flowers, Roots, Seeds, Farrinas [wheats]" as well as the tools.17

For conserves (jams or jellies made from dried substances), Nicholas Culpeper advised "keeping them, is in Earthen Pots."18 He said that "some keep many years, as Conserves of Roses: others but a year, as Conserves of Borrage [borage or star flower], Bugloss [Anchusa officinalis], Cowslips [Primula veris], and the like."19 To make it easy for the reader, he explains that the conserve is 'almost spoiled' when it forms "a hard crust at top with little holes in it, as though worms had been eating there."20

Photo: Wiki User cyclonebill - Red Wine Apricot Preserves

Culpeper separates preserves (jams made from fresh fruit with chunks of the fruit still in it) into four types based on what they're made from: flowers, fruits, roots and barks. He admits flowers are rarely made into preserves. He goes into greater detail on how to make fruit and root preserves, which appear to have been common. His use of the word 'barks' is a bit misleading. Culpeper admits that he can only think of bark preserves being made from "Orenges, Lemmons, Citrons, and the outer Bark of Walnut which grows without the shell"21. We would call these marmalades.

Preserves are to be "kept in Glasses, or glassed pots. The preserved flowers will keep a year if you can forbear eating of them; the Roots and Barks much longer."22 Culpeper has good things to say about preserves as a way to both make medicines "pleasant for sick and queazy stomachs" and preserve the ingredients "from decaying a long time."23

A curious medicine to the modern ear are lohochs, a word which the often acerbic Culpeper says "in plain English signifies nothing else, but a thing to be licked up"24. "They are in Body thicker than a Syrup, and not so thick as an Electuary."25 Lohochs are to be "kept in pots, and may be kept a year and longer."25

Artist:

Caspar Luyken

Apothecary Making a Prescription (1695)

Robs (what we would call extracts) are a concentrated form of fruit juice which are strained and boiled "till (being cold) it be of the thikness of Honey"26. Culpeper doesn't give any more information on them, although extracts, if kept well sealed, "will generally last (maintain quality) indefinitely until they evaporate."27

In fact, it is likely due to this quality that James Lind, who was working on the cure for scurvy in the mid 18th century "became obsessed with concentrating citrus juice to make it more practical" for use at sea.28 He felt that by keeping the heating temperature of the fruit juice below boiling, the "virtues of twelve dozen lemons or oranges, may be put into a quart bottle, and preserved for years."29 Unfortunately, the heating process destroyed the antiscorbutic properties of the fruit juices, so this failed to work as a scurvy cure.

For Ointments, Culpeper directed the reader to use herbs and hog's grease beat together "very well together in a stone Morter with a wooden pestle, then put it in a stone pot (the Herbs and Grease I Mean, not the Mortar)"30. The ointment was then "to be kept in pots, and will last above a yeer, some above two yeer.”31

Although Culpeper does not comment on keeping unguents (the ointments' more oily cousin), John Woodall gives some advice on revitalizing them, noting that if they became "be too hard or dry, you may mixe oyle of Roses or Linseed" with them"32. Woodall does not comment on how they are to be kept, although the July 9th, 1712 The Spectator mentioned that unguents could be found in gallipots, presumably sealed with leather tied down with string.33

For plasters, we tend to think of plaster casts, but those used during the golden age of piracy were made of more varied ingredients such as "Mettals, Stones, divers sorts of Earth, Feces, Juyce, Liquoris, Seeds, Roots, Herbs, Excrements of Creatures, Wax, Rozin, Gums.”34 Since they were made to become stiff when they air dried, they would be made up not long before they were needed.

When John Moyle described his dressing box, which served as a sort of mobile first aid kit that the surgeon's mate or assistant would prepare daily to

Woman Making Poultice, From an Herbal

In the Wellcome Collection

dress the men with minor wounds, he notes that the box has "a place for Plaisters ready spread."35 Woodall likewise explains that plasters were to be spread when the surgeon's mates made their daily "visite [to] the Cabines of men, to see who hath any sicknesse or Imperfection"36.

Poultices (or cataplasms) were "a very fine kind of Medicine to ripen sores."37 Culpeper explains them well, "They are made of Herbs and Roots, fitted to the Disease and member afflicted, being chopped small, and boyled in Water almost to a jelly, then by adding a little Barly meal, or meal of Lupines, and a little Oyl, or rough sheep suet, which I hold to be better, spread upon a cloth and applied to the grieved place."38 Like plasters, they would be made not long before they were needed since their operation depended on dampness.

Culpeper says that troches (or lozenges) were invented to allow "Powders being so kept might resist the intromission of Air, and so endure pure the longer."39 This allowed someone to conveniently carry his medicine "in a paper in his pocket (while a man travels) and [is] more convenient behalf than to lug a Gallipot along with him."40 Culpeper doesn't say how long they are good for, but he does advise the reader to "keep them in a pot for your use.”41

Of course, the actual time a particular medicine in a particular form would remain viable would depend not only on the type of medicine it was but also on the ingredients included. As a result, these comments would have been more of a rule of thumb.

1,2,3,4 Nicholas Culpeper, The English Physitian, 1666, p. 275; 5,6 Culpeper, p. 276; 7,8,9,10 Culpeper, p. 277; 11 Culpeper, p. 278; 12 "Shelf Life of Oil", Eatbydate.com, gathered 4/19/15; 13 Culpeper, p. 278; 14 Culpeper, p. 278-9; 15 Culpeper, p. 279; 16,17 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1702, p. 41; 18, 19, 20 Culpeper, p. 279; 21 Culpeper, p. 280; 22,23,24,25 Culpeper, p. 281; 26 Culpeper, p. 274; 27 "Extracts", shelflifeadvice.com, gathered 4/19/15; 28 Stephen R. Bown, Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentleman Solved the Greatest Medieval Mystery of the Age of Sail, p. 118-9; 29 James Lind, quoted in Bown, p. 119; 30 Culpeper, p. 281; 31 Culpeper, p. 282; 32 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 48; 33 The Spectator: Volume the Sixth, No. 426, Wednesday, July 9th, p. 122; 34 Culpeper, p. 282; 35 Moyle, p. 43; 36 John Woodall, 37,38 Culpeper, p. 282; 39,40,41 Culpeper, p. 283