Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Next>>

The Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory, Page 12

Sea Surgeon Concerns - Substitute Medicines

While sea surgeon John Moyle's recommendation to favor

medicines with compounded ingredients for treating multiple illnesses sounds like a good idea, it resulted in a different problem: the possibility of receiving adulterated medicines. This could occur in two different ways.

Artist: Thomas Rowlandson

The Dance of Death; The Apothecary, Wellcome Collection (1816)

In the first, the sea surgeon could request medicines made with cheaper medicines since most patients wouldn't know any better. In the second, less-than-honest apothecaries could change the more expensive ingredients in a complex prescription to make a greater profit on the sale. Most examples of these behaviors come from the Naval sphere; it would be difficult to monitor the behavior of merchant surgeons who hired on on their own terms.

In 1673 James Pearse (the Surgeon General of the Navy), John Knight, Henry Barker and Henry Johnson recommended that "three or four able apothecaries conversant in preparing medicines for the Sea be appointed to supply his Majesty’s Ships with medicines, as at present the Surgeons frequently furnish their chests in obscure places in the remote parts of the town, and thereby sometimes escape their being examined, and they are frequently furnished with unwholesome drugs and ill-made medicines."1 Sea surgeons were given money in advance of a voyage to purchase their consumable tools and medicines before the ship left. If they could purchase their chests for less than they were allotted by the ship's owners, they could pocket the difference.

As a result of such problems, the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries began supplying the naval fleet's medicine chests based on an order dated July, 1703.2 This may not have solved the problem of adulterated medicines, however. Writing in 1742, sea surgeon John Atkins said,

There is a Difficulty to the best Judges in distinguishing many Medicines, especially as to the true Dispensation, and when they have dear [expensive] Ingredients, and may be disguised with others cheaper; the [Apothecary's] Hall should be watched against both, in Justice to the Surgeon, and the Sailor, who ought to swallow nothing but what is fit for a Prince in the same Case: the properest Caution is to allow Navy Surgeons who pay the viewing Charges, to give it one or two Eminent Apothecaries to Inspect for them: They are the best Surveyors of their own Goods.3

From Apothecaries in a French Pharmacy (1740-50)

Atkins goes on to say that prescriptions "with some rare or costly Ingredients, carry a Temptation, I say, to adulterate; and Mr. [John] Quincy [author of Pharmacopoeia Officinalis & Extemporanea], who has writ the best upon Dispensing them, lets us know in several Places what may be left out or changed (Quid pro quo) to make the Medicine better and save Money: I would therefore by this Proposal have the Hall paid for the Real, and not the Dispensatory Receipt; which in some, by Artists, can be made to exceed a double or treble Value."4

Counterfeiting medicines was an industry unto itself. As noted earlier, sea surgeon John Woodall worked for several months with an apothecary in Holland who made imitation mithridate and Venice treacle.5 Like Woodall, the main character in sea surgeon Tobias Smollet's book about the life of (fictional) sea surgeon Roderick Random found himself working for an apothecary whom he said could

Make up a physician’s prescription, though he had not in his shop one medicine mentioned in it. Oyster shells he could invent into crab’s eyes; common oil into oil of sweet almonds; syrup of sugar, into balsamic syrup; Thames water, into aqua cinnamoni; turpentine, into capivi; and a hundred more costly preparations were produced in an instant, from the cheapest and coarsest drugs of the material medica: and when any common thing was ordered for a patient, he always took care to disguise it in colour or taste, or both, in such a manner as that it could not possibly be known.6

Although the account is fictional, the specificity of the details hint that

From Apothecaries in a French Pharmacy (1740-50)

Smollett may have seen these practises at work when he himself was practising.

Even John Moyle, who advised the use of compound polypharmaceuticals as being most economical shipboard admitted "in many Compound Medicines, a very knowing Many may be deceived, and not know if they were truly dispenced"7.

In order to supply his sailors with the correct medicines, a wise surgeon would have been one who knew what he was getting, no matter the source. Moyle advises his readers, "if you have had any experience in Medicines, then either by the sight, smell, taste or consistence, you will perceive (within a little more or less) whether the Medicine be sound or sophisticated."8 Failing that, Moyle suggests to his readers "to see (your self) that the Medicines you put up are good… [for] your self is the Man whose Reputation must stand or fall, according as your Medicines operate on the Sick or Wounded, and that is another great Reason that you should look to it."9

1 Cited in John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, p. 151;2 Charles Raymond Booth Barrett, The history of the Society of apothecaries of London, 1905, p. 120; 3 John Atkins, "Introduction", The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 12; 4 Atkins, "Introduction", p. 12-3; 5 "John Woodall. 1570–1643", British Journal of Surgery, p. 369; 6 Tobias Smollett, The Adventures of Roderick Random, 1748, p. 116; 7 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 40; 8 Moyle, p. 41; 9 Moyle, p. 40

Sea Surgeon Concerns - Medicine Quantities

Like most supply problems, the sea surgeon wanted to balance concerns about having enough medicines to last the duration of a voyage with not to have too much left over after it was completed.

John Moyle has the most to say about managing the quantities of medicines required by a surgeon at sea. He begins with a bit of grousing, explaining that while experienced Naval surgeons had a pretty good idea about how much of various medicine they required, the governing body "will not suffer less quantities of Medicines to pass than is sufficient; therefore you must submit to their discretion."1

Moyle goes on to give his thoughts on what he feels is sufficient,

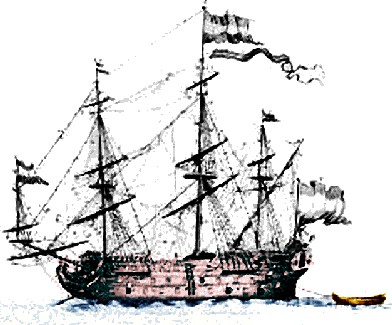

2nd Rate English Ship - HMS Coronation (1689)

When I have gone in a Second Rate (a ship carrying approximately 90 guns at that time2) , I commonly put up {3 pounds} a piece of them Electuaries, Syrups, and Cordial Waters that are given by greater quantities in the dose, and most frequently used and expended at Sea, and the like [amount] in Oyls, Unguents and Emplasters, and have regulated the quantities of the rest of my Medicines accordingly; still minding the present Expedition, and taking extraordinary of them things that I expected would be most used there"3.

He goes on to says when he was in a fourth rate ship (one having about 60 guns4) "you will not seem to need so great quantities as the Second, because you have a less Compliment of Men"5. Having said that, Moyle goes on to explain that he took the same amount of most medicines when he was traveling on a fourth rate because of the length of the voyage, "for the great Ships [first, second and third rate] seldom stay out above eight or ten Months, whereas the smaller [ships - fourth, fifth and sixth rates] are many times kept out eighteen or twenty Months, and that before any recruit [renewal of the supply of medicines] can be had, (especially when they are sent out Foreign Voyages)."6

Moyle also discussed the quantity of medicines required for a merchant ship. Like most of his advice it was practical, suggesting the sea surgeon base the quantity of medicines needed on the number of Men, "the supposed length of your Voyage, as also what is likeliest to happen; and how long it may be ere you may have a recruit."7

Moyle goes on to give a little more detail from his travels on merchant ships to the West Indies. "I used to take {1.5 pounds} of each of the Electuaries Syrups, Waters, Oyls, Unguents, and Plasters, that are commonly most expended at Sea, and less of other things... and this I have found sufficient."8 He also notes that ships "bound to the

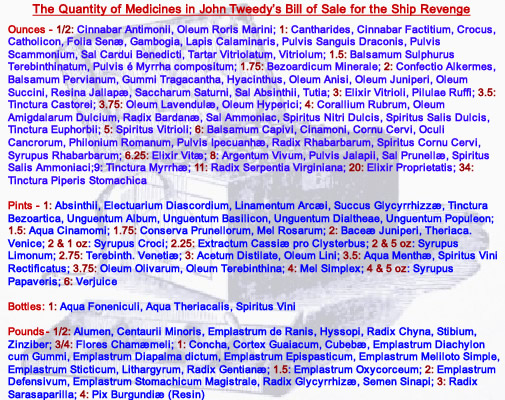

Quantities of Medicine for the Privateer Revenge, From John Tweedy's Bill of Sale (1743)

Thanks to Brian Chabot for Helping Clarify One of the Measurement Units

East-Indies, and other long Voyages, carry greater quantities, because of the length of the Voyage and sickly Climates they go into"9.

Moyle's advice does give some guidance, although it paints the quantities a ship might need in rather broad strokes. The only list of sea surgeon's medicines that includes specific quantity breakdowns comes from the Bill of Sale written by John Tweedy for the Revenge.10 It should be noted that a 1741 privateering voyage of the Revenge lasted about 4 months.11 When the ship left New York for that tour, it had 61 men on board.12 So the quantities shown here would likely correspond to those statistics.

It is interesting that the largest quantities of medicines purchased were used as bases for other preparations and pain remedies. Examples of medicines used in preparations include Oleum Olivarum (Olive Oil), Mel Simplex (Honey), Verjuice (an acidic juice used like vinegar) and Resin (used to make topical ointments for burns and wounds). Pain remedies purchased in quantity include Spiritus Vini (Brandy) and Syrupus Papaveris (poppy juice, an opiate).

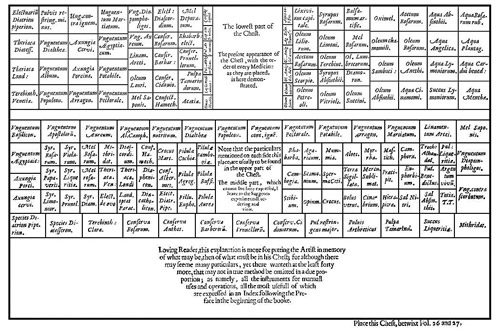

Our other sea surgeon who details the medicines to be taken to sea is John Woodall. He doesn't give any

John Woodall's Medicine Chest Layout, Insert Opp. p. 26 (1639)

quantity suggestions in his list, but he does provide a chart of his medicine chest (seen at right) that hints at how the space occupied by medicines. Although the scale of this chart is not know (nor is the accuracy of this chart), it is possible to get an idea which medicines were in greater demand by looking at the relative size of the spaces provided for each medicine.

In addition to that, some medicines appear in the Woodall's medicine chest more than once, suggesting their popularity. Two medicinals appear in three different places: electuarium diatrion piperion (black pepper elixir - used for stomach troubles) and mel rosarum (honey of roses - used in enemas for diarrheas and dysenteries). A variety of unguents for treating burns and other topical pain appear in two places in the chest such as unguentum contra ignem, unguentum martiatum, unguentum dialtheae and unguentum diapompholigos. Woodall also puts his faith in compound polypharmaceuticals used to treat a variety of illnesses; Venice Treacle and Mithridate both appear twice in his medicine chest.

1 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 36; Based on the ships listed in "The “Thirty Ships” programme of 1677 (1677–1688)", List of ships of the line of the Royal Navy, wikipedia, gathered 5/19/15; 3 Moyle,p. 37-8; 4 "List of ships-of-the-line of the Royal Navy (1688-1697)", List of ships of the line of the Royal Navy, wikipedia, gathered 5/19/15; 5,6 Moyle,p. 38; 7,8,9 Moyle,p. 39; 10 See "158. John Tweedy’s Bill for Medicines. November 8, 1743". Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period Illustrative Documents, John Franklin Jameson, ed., p. 456-61; 11 See Peter Vezian, “145. Journal of the Sloop Revenge. June 5-October 5, 1741”, Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period, John Franklin Jameson, ed., 1923, p. 381-429; 12 Vezian, p. 396

Sea Surgeon Concerns - Keeping Medicines

"In foreign Parts the Country must be unblessed that will not afford an Equivalent to musty decay’d Drugs, for spoil, they will, and sooner in warm Climates." (John Atkins, "Introduction", The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 13)

A big problem with medicines for long voyages at sea was how to keep them from going bad. Fresh simples (such as herbs and plants) could not be taken because of their short shelf life. As sea surgeon John Woodall asks why "should I spend my time in teaching that method, or those medicines to the Surgeons Mate, which will not bee had at sea"1, suggesting the problem of keeping such fresh medicinals on board for treatment.

John Atkins warned his readers that electuaries, conserves, syrups, roots, herbs and flowers could decay while plasters, oils and ointments could either become dry or rancid.2 Atkins was an advocate of allowing the surgeon to choose his medicines rather than the "Apothecaries or their Friends governing ...on Shore"3. For this reason. "Regard should be had to Surgeons in the Choice and Quantity taken of Medicines. He has gone through the Trials, and is the fittingest Judge of what will be wanted, at least, a Society of the Eldest [sea surgeons] will"4.

Although Atkins casts aspersion on the apothecaries, they did recognize the useful life of simple medicinals. For example, when discussing simples, Nicholas Culpeper noted that seeds "will keep a good many years; yet this I say, They are the best the first year"5. He also advised that "Such Roots as are great [large], will keep longer than such as are small: yet most of them will keep a year."6 With this in mind, a sea surgeon could choose roots over less durable parts of a plant if he wanted to have a source of that simple available to him.

In addition, drying parts of simples that might not otherwise survive such as flowers and leaves could also serve the sea surgeon's needs. (For more on this, see the section on processing medicines discussed previously.)

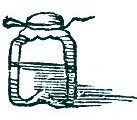

Double Wall Square Bottle

Sealed and Pricked,

From Cours d'Operations,

p. 835 (1740)

Proper storage and sealing of medicines would also allow them to last longer. Sea surgeon John Moyle provided a variety a practical ideas in this area. He advised the sea surgeon to use "square double Glass Jars and Bottles, than Gallipots; for these will fit the partitions in your Chest better than the others, and indeed will preserve your Medicines cooler and better."7

For "Fermenting Medicines" the common sense Moyle told his readers to make sure the bottle was larger than the contents "that there may be room to ferment"8. He told them to make sure that medicines were "covered well that the Air spoil them not. And let not the Syrup Bottles that will ferment, be Corked, but only their Covers tyed hard down and pricked."9 He also ordered that "when you are at Sea, be often stirring down your fermenting Electuaries, and if any of them grows dry, mix some of the humid ingredients with it, whereof it was made; as Honey to some, and Sugar to others."10

By making use of all these ideas, the sea surgeon could rest assured that his medicines would last as long as possible.

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 178; 2 John Atkins, "Introduction", The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 13; 3,4 Atkins, "Introduction", p. 14; 5 Nicholas Culpeper, The English Physitian Enlarged, 1666, p. 272; 6 Culpeper, p. 273; 7 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 41; 8 Moyle, p. 41-2; 9,10 Moyle, p. 41-2

The Period Sea-Surgeon's Dispensatory That Almost Was

The purpose of this article is to create a dispensatory such as might have been written specifically for sea surgeons during the golden age of piracy using period sea-surgeon's books to build the list of ingredients. While such a dispensatory

_Jan_Claesz_Rietschoof_(1652-1719).jpg)

Artist: Jan Claesz Rietschoof

Schepen in de haven bij kalm weer door (Ship in Harbor in Calm Water) (Late 17th/Early 18th)

never actually existed, one of our period authors actually did consider writing one.

In The surgions mate, sea-surgeon John Woodall said,

I purpose, God willing, as soone as I can have time to publish also the true preparations & uses [of medicines for use by sea surgeons], having received some of them from learned Physitians, and expert Surgeons amongst my good friends heere and there as I could gather them, being things of their owne experience, and to me now confirmed by mine also.1

Unfortunately Woodall never published such a book. Fortunately, Woodall's book The Surgions Mate does include quite a bit of information about medicines with sea surgeons in mind. He does not list the ingredients of such medicines, instead focusing on how the more practical aspects of how these medicines were used. Had Woodall finished the book he 'purposed', it would most likely have started with the information in The Surgions Mate and built upon it in the way this article does.

1 John Woodall, "To the Reader", the surgions mate, not paginated