Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Next>>

The Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory, Page 3

Medicine Use

The medicines used during this time were all based in nature, being obtained primarily from plants. What wasn't plant-based was derived from animals and metals.

Medicine Preparation

This created a wide variety of potential medicines - many things (and nearly, if not actually, all things) were tried as remedies throughout the ages.

Period medicines could also be combined with other substances to make them more palatable to patients. As sea surgeon John Moyle said, "You must carry Medicines of divers forms, yet having one and the same virtue; and that because some Patients cannot take every form of Medicine."1

In addition to the natural substances, some forms of medicine were 'created' using chemical processes to refine them and isolate the most important elements, thanks largely to the impact of Paracelsus' work.

Let's look at this concept in more detail.

1 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 5

Medicine Use: Variety

"...whereas the species of diseases are infinite, so also the Remedies both simple and compound, that are to be appropriated there-unto, are almost unnumerable." (Jean de Renou, A Medicinal Dispensatory, pp. 6-7)

Photo: David Hawgood of nationalgeopraphic.org.uk

The Chelsea Physic Garden (Crocosmia Aurea), established

in 1673 by the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries

Even before the creation of compound medicines (which contain multiple 'simples' or original medicinal elements) and chemical medicines, the world offered physicians a wide variety of potential medicines. Many animals, minerals and plants were employed as medicinals throughout history. In the 1677 Pharmacopoeia Collegii Regalis Londini (the fourth edition of the London Pharmacopoeia which was in force during much of the golden age of piracy) were listed 1168 elements of simples (with a further 178 when plant subspecies were included) and 770 compound medicines.1 The simples include 133 Roots (with 47 more if you include the subspecies), 39 cortices, 17 woods (with 2 more subspecies), 269 grasses and leaves (with 62 more subspecies), 73 flowers (11 more subspecies), 81 fruits (40 more subspecies), 130 seeds (16 more subspecies), 68 gums and resins, 16 juices, 12 items grown on plants, 28 animals, 179 animal parts, 17 minerals, 17 salts, 39 stones and 33 metals.2

The number of simples included in the above numbers contain a great deal of overlap of plant species. This was because different parts of the same plant are listed separately because "each part had powers to cure different diseases and different parts of the body."3

This large variety of medicaments also provided the patient with alternatives, which was important "given constraints of cost and availability [of some medicinal plants], patient choice concerning taste, etc."4

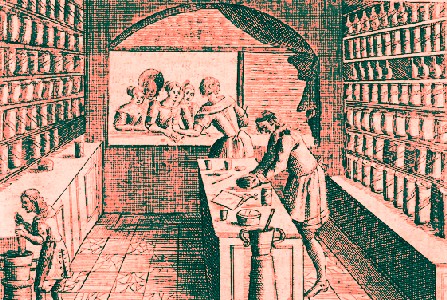

Some of the Many Medicines In A Period Apothecary's Shop,

From Georgica Curiosa Aucta, by Wolfgang Helmhard Hohberg (1697)

However, even though the number of known medicines "was expected to increase with each generation"4, a counter-movement recommended a reduction in variety so that apothecaries didn't have to keep unnecessary supplies of rarely used plant and animal elements on hand. In the preface to Nicholas Culpeper's 1659 Culpeper's School of Physick, William Ryves notes,

the practical part of Physick, do swell to no purpose with such infinite variety of medicaments that the practitioners are confounded, as not knowing amongst so many which of them to choose. Mr. Culpeper being truly sensible of this their error, made it it his business not to puzzle his young students with the multiplicity of Medicines, but onely to select and set down such as are most proper, choice and effectual against the disease.5

A look at the variety of elements listed in Culpeper's herbal may suggest that he could have done a lot more selecting. Culpeper does subtly comment on the lack of effectiveness of some of the medicines he copies from the London Pharmacopoeia, often in an amusing, sarcastic fashion. For example, his pithy comment on unguentum potabile: "I know not what to make of it"6, suggests he sees no use for the medicine.

Still, the wide array of recommended medicines persisted and grew throughout the early eighteenth century. Some removal of medicinals from the official pharmacopoeias began near the end of the golden age of piracy. For example, the 1722 edition of the Scottish Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia "had left some things out, it contended,

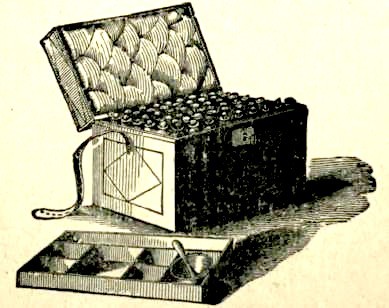

A Large Medicine Chest with Plaster Box in the Foreground

'as not differing from others in virtue, or as having been introduced by superstition or credulity of antiquity'."7 However, It wasn't until the late 18th and early 19th century that Pharmacopoeias began to make serious efforts to trim the unused and unusual medicines from their texts.8

As a result, the sea surgeon had a wide variety of medicinal elements from which to choose. Unfortunately shipboard space was always at a premium, particularly on merchant vessels. The sea surgeons were forced to consider what would best survive a long voyage, which made them more choosy than the writers of the medicinal books for land-based physicians and apothecaries.

As mentioned previously, the largest number of medicines recommended for sea surgeons to take with them were found in John Woodall's 1617 book at 299 simples, compounds and chemicals9. While this is a fairly large list, it is a far cry from the College's 1938 simple and compound medicines. John Moyle's book, first printed in 1693, contains only 152 prepared simples and medicines and 29 specified compositions (which were to be made from the simples as was needed).10 John Tweedy's 1743 Bill for Medicines was at the bottom with a mere 118 medicines.11 While the data we have to work with is rather limited, the decline in the number of medicines over time does reflects a similar trend in pharmacopoeias in the mid and late 18th century. The sea surgeons implemented the paring of medicines strategy about a century earlier, most likely out of necessity.

1 Royal College of Physicians of London, Pharmacopoeia Collegii Regalis Londini, pp. 1-20 & Index, based on the author's calculations; 16; 2 Royal College of Physicians of London, pp. 1-20, based on the author's calculations; 3 Andrew Wear, Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680, p. 91; 4 Wear, p. 80; 4 Wear, p. 81; 5 Cited in Wear, p. 81; 6 Nicholas Culpeper, Pharmacopœia Londinesis, p. 228; 7 David L. Cowen, Pharmacopoeias and Related Literature in Britain and America, 1618-1847, Ashgate Valiorum, Burlington, USA, 2001, p. 38; 8 Cowen, p. 39 9 Determined by the author using John Woodall's the surgions mate, 1617, pp. 40-124 & 283-6; 10 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1702, p. 10-5, 17-20, 23-6, 28-33; 11 John Franklin Jameson, ed., "158. John Tweedy’s Bill for Medicines. November 8, 1743". Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period Illustrative Documents, p. 456-61

Medicine Use: Forms

Giving Medicine, From De Efficaci Medicina

Libri Tres, by Marco Aurelio Severino (1646)

"...there was a variety of ways in which a herb could be prepared and made into medicines, and this often meant that, for instance, a syrup was appropriate for one illness and a pill for another." (Wear, p. 91)

As sea surgeon John Moyle's previous quote suggests, some patients preferred particular forms of medicines over others.

One cannot take a Bolus [a small round soft mass], another cannot swallow Pill, and some cannot drink a Potion. Now a Patient must not be lost because he cannot take such a particular form; Therefore if his Stomach nauseates one form you must have another that he can away with, yet having the same power as the former.1

French physician Jean de Renou agreed that military physicians are best served by being "furnished with variety of operating Medicaments for help and comfort, whereby they have oftentimes freed themselves and Army from great perils that would otherwise have accrued, and sometimes from death it self."2

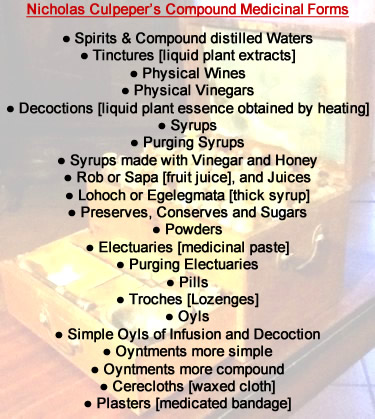

Forms of Medicine Culpeper's Pharmacopœia Londinesis

There were a large variety of ways to administer medicines. Nicholas Culpeper's "Table of Compounds" in the index of his book includes 21 different ways to prepare medicines from the raw simples3 which are listed in the chart at left.

Most medicinal simples were compounded in some way for easier delivery. Compounding can involve the mixture of multiple simples, or the processing of simples from their natural state, which is why Culpeper sometimes differentiates between simple and compounded compounds (such as he does for 'Oyntments'). The organization of simples and compounds will be discussed in greater detail in the section on Medicinal Books Organization.

Nearly every consistency of medicine from water to powder can be found in Culpeper's list, including some rather fine variants, like lohochs (thick syrups) and electuaries (pastes). Clearly there was interest in providing patients with a wide variety of medicine types to chose from.

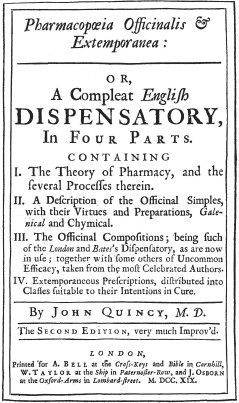

Of course, the form of a medication is only as good as its preparation. English apothecary John Quincy makes several comments on the preparation of some of the medicine forms that hint at the need for different forms while providing some insight into their composition.

Quincy advised that decoctions (liquid plant essences made by heating) were best made with dried herbs

Quincy's Pharmacopoeia Universalis, 1719

because they were

much fitter ...because the most forcible Pressure [on] a green Plant, must still leave some Portion behind; and that most probably [is the part] which is the best, as the thin watry Parts run off first... but when a Plant it dry'd, which robs it only of the Phlegm or Water, boiling Water naturally opens its minutest Cells, and joins with the Essential Salts, and most material Parts of all.4

He suggested the same thing was true for syrups because the liquid base made from dried herbs "will be both finer and keep longer, as well as be stronger of the Ingredient."5

Quincy explains that the reason troches (lozenges) were created "seems to have been to preserve [medicines] in readiness for present Use, [especially] Substances which stood in need of some Preparation, and took up time to reduce into Powder, and which by lying in a dry Powder would likewise be subject to decay sooner than in this Form."6 In addition, he suggests that this form is useful to some patients because it allows gradual "dissolving in the mouth, as [is done with] most of the Balsamick and Pectoral kind"7.

When discussing plasters (or 'emplasters'), Quincy discusses the usefulness of their form to application to wounds. He explains that they are "a Composition of Oils, Waxes, Resins, and Powders, &c. in such a Consistence as will keep its Form without running or sticking to any thing when cold, but is yet moist enough to be melted and spread, so as to adhere when warm, and not be brittle or dry enough to crackle or break off what it is spread upon."8

Quincy also discusses balsams, which Culpeper variously lists under his simple and compound 'Oyls of Infusion and Decoction'. Quincy notes that a balsam "is somewhat thicker than a common Oil; and sometimes the Name is also apply'd to such Substances as are of the Consistence of an Unguent"9. His section on Balsams

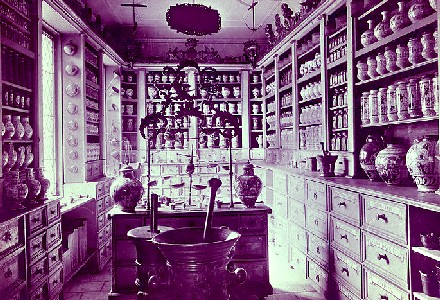

A Variety of Jars for a Variety of Medicines - 17th c. German Apothecary's Shop

Image from the Wellcome Museum

includes 22 concoctions, half of which are titled 'oil' and half 'balsam'.10

He includes some oils in this section, noting that they are different than regular oils. They "are such as are impregnated with some Medicinal Simples, generally Leaves or Flowers of Vegetables, by Boiling or Insolation."11

Quincy explains that 'insolation' is "steeping the Ingredients in Oil for use: because Boiling is apt to dissipate and lose the better part of the Flowers"12. Insolation draws out and preserves the natural scent. (Scent was considered an important part of the patient's experience of medicines.) He goes on to explain the steps required. First, "strain out the Oil, and afterwards pouring it into a clean Pan, let it stand over a gentle Fire, until by frequent trials upon white tile, it arrives to a high unmix'd Green: for this way the Colour will very much heighten... This Management also quite driving away all aqueous Particles, it will keep much the longer, without change of Colour or growing rancid."13

Culpeper does not include any of Quincy's listed balsams in his book, but he does include recipes for eight of the oils: Oleum Anethium (oil of dill) Oleum Excestrense (oil of exeter), Oleum Capparibus (oil of capers), Oleum Castelorum (oil of poppies), Oleum Hirundinum (oil of swallows), Oleum Hyperici (oil of St. John's wort), Oleum Lumbicorum (oil of earthworms), Oleum Rosarum (oil of roses) and Oleum Scorpionum (oil of scorpions).14

Another form of medicines were compounds that were sometimes called polypharmaceuticals. Polypharmaceutical medicines contained several ingredients, sometimes dozens of them. These ingredient-intense remedies were sometimes referred to as panaceas because they

Lionel Lockyer Allegedly Adding Sunbeams to His Pills, From His Advertising Broadsheet,

Image from the Wellcome Museum, London (mid/late 17th century)

were thought to have wide application. Historian Andrew Wear identifies a couple of these including mithridatium, theriac, Daffy's elixir (a cure-all invented by clergyman Thomas Daffy in 164715) and Lockyer's pills (a mid-17th century 'miracle pill' invented by quack Lionel Lockyer which he claimed contained sunbeams among its other ingredients16) Wear notes that these were thought by some to "cure all manner of diseases."17

While Nicholas Culpeper included some of the 'legitimate' polypharmaceuticals in his book (those appearing in the London Pharmacopoeia), he doesn't seem to have had a very high opinion of them. In Culpeper's entry on mithridate - a panacea containing as many as 65 ingredients18- he warned, "Authors have spent more time about this and Venice Treacel (both of them being terrible messes of altogether) in reducing 'em in Glasses, than ever they did in saying their prayers."19

Sea surgeon John Moyle brought up another problem with these panaceas, warning his surgical readers "that in many Compound Medicines, a very knowing Many may be deceived, and not know if they were truly dispenced"20. Still, he doesn't dismiss them entirely, advising that "if you have had any experience in Medicines, then either by the sight, smell, taste or consistence, you will perceive (within a little more or less) whether the Medicine be sound or sophisticated."21

1 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 5; 2 Jean de Renou, , A Medicinal Dispensatory, pp. 2; 3 Nicholas Culpeper, Pharmacopœia Londinesis, Index - Table of Compounds; 4,5 John Quincy, Pharmacopoeia Officinalis & Extemporanea, 1719, p. 372; 6 Quincy, p. 415-6; 7 Quincy, p. 416; 9 Quincy, p. 461; 8 Quincy, p. 445; 10 Quincy, p. 445-52; 11 Quincy, p. 445, emphasis mine; 12,13 Quincy, p. 445, 13 See Culpeper, pages. 214-9; 15 Daffy's Elixir, wikipedia.com, gathered 4/11/15; 16 Lionel Lockyer, wikipedia.com, gathered 4/11/15; 17 Andrew Wear, Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680, p. 81; 18 Mithridate, wikipedia.com, gathered 4/11/15; 19 Culpeper, p. 164; 20 Moyle, pp. 40; 21 Moyle, pp. 41