Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Next>>

The Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory, Page 8

Medicinal Books: Of Herbals, Pharmacopoeias, Dispensatories and Sea Surgeon's Books

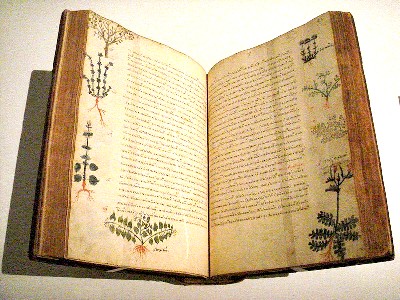

As medicines developed, so did the books that explained their properties, uses, and recommended compositions. The earliest such manuals were herbals - books listing plants and their uses for various illnesses. Medical historian

Photo: Wiki User Phgcom

Dioscorides De Materia Medica (15th c. Byzantine)

Charles Singer explained, that most of the remedies listed were "quite devoid of any rational basis. It may be taken for granted that the writer of a herbal

is unable to treat evidence on a scientific basis. He makes a ‘direct attack’ on disease, without any ‘nonsense about theories.’ The herbal is thus to be distinguished from the scientific botanical treatise by the fact that its aims are exclusively ‘practical’"1.

From the herbals came pharmacopoeias. Pharmacopeia was derived from ancient Greek words which, when strung together, basically meant 'drug-mak-ing'.2 This term was first used by 3rd Century Greek biographer Diogenes Laërtius, in his Lives of the Philosophers. Its earliest use as a title was for French physician Jacques du Bois' (Sylvius') Pharmacopoeia, liber tres, published in 1548. From there, authors all over Europe in the mid-16th century employed it in their title. As a result, "the word ‘pharmacopoeia’ was more consistently used for books of formulae having legal force in the regions for which they were issued.”3 The word 'pharmacopoeia' eventually came to suggest "government involvement in the protection of public health, since it sought not merely to provide standardization of the material medica but also to guarantee that the pharmacist dispensed what was prescribed."4

For a more detailed account of the history of herbals and pharamacopoeias that preceeded the London pharmacopoeia, see the article A Brief History of the Early Medicinal Books.

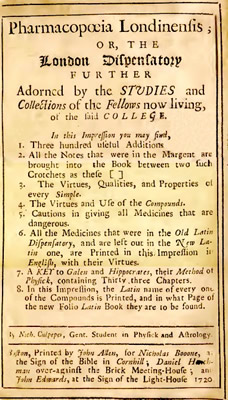

Nicholas Culpeper's Pharmacopoeia

Londinensis Title Page (1720) However, as its official capacity as a drug making manual came to the fore, the pharmacopoeia evolved into nothing other than lists of drugs and formulas, containing little information on how the drugs were to be used."5

During the golden age of piracy, official pharmacopoeias were printed in Latin (which, as Nicholas Culpeper waggishly noted when discussing such terms, was done by physicians "because you should not know what they mean"6.) Such books would probably be of only limited use to the average surgeon, who, although he was "expected to have at least a smattering of Latin", often learned his practice through an apprenticeship.7

As medical historian David L. Cowen says,

There was the a clear need for a companion publication that would describe drugs, give indications for their use, and provide some account of professional experience with the drugs in question. This kind of book, the dispensatory, became something of a British specialty in the late seventeenth and the eighteenth century.8

Artist: Jacob Knyff

English & Dutch Ships Taking on Stores (1673)

The term 'dispensatory' was used almost interchangeably with that of 'pharmacopoeia' in the late 16th century. Edward Kremers and George Urdang note that in England "'dispensatory' came to designate a kind of commentary which embraced the text of the pharmacopeia"9.

Many of those published during the golden age of piracy were written in English, such as Nicholas Culpeper's 1653 publication, Pharmacopœia Londinensis, or, The dispensatory and John Quincy's 1718 Pharmacopoeia Officinalis & Extemporanea: or, A Compleat English DISPENSATORY, In Four Parts. The use of 'pharmacopoeia' in their titles was a reference to the official publication by the College of Physicians in London from where they had drawn the recipes for the medicines.

Nearly all of these disensatories had their roots in the London or Edinburgh Pharmacopoeias.

1 Charles Singer, “The Herbal in Antiquity and Its Tranmission to Later Ages”, Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 47, p. 1; 2 "Pharmacopoeia," wikipedia.com, gathered 2/28/15; 3 L.G. Matthews, Footnote, “Herbals and Formularies”, From The Evolution of Pharmacy in Britain, Edited by F.N.L. Poynter, 1965, p. 208-9; 4 David L. Cowen, Pharmacy An Illustrated History, p. 91;5 Cowen, p. 100; 6 Nicholas Culpeper, Pharmacopœia Londinesis, p. 204; 7 F.N.L. Poynter, "Introduction," Selected Writing of William Clowes, 1948, p. 14; 8 Cowen, p. 100; 9 Kremers and Urdang’s History of Pharmacy, 4th ed., Edited by Glenn Sonnedecker, p. 278

Medicinal Books: The London Pharmacopoeia

The London Pharmacopoeia has its roots in King Henry VIII's Letters Patent which constituted the College of Physicians.

Royal College of Physicians, London. Architect

Roger Hooke, Wellcome Collection (17thc.)

This "provided for the election of four persons appointed by the College to have the supervision and scrutiny of every kind of medicine and the prescription thereof by physicians practicing within a radius of seven miles of the City of London."1 Another Act of 1540 gave them the power to "destroy defective stock."2

The publication of an actual pharmacopoeia by the College was discussed in 1585, "but as it ‘seemed a toilsome task’ the idea was deferred for further discussion."3 It came up again in 1589, "when it was ‘proposed, considered and resolved that there shall be constituted one definite public and uniform dispensatory or formulary of medical prescriptions obligatory for apothecary shops’."4

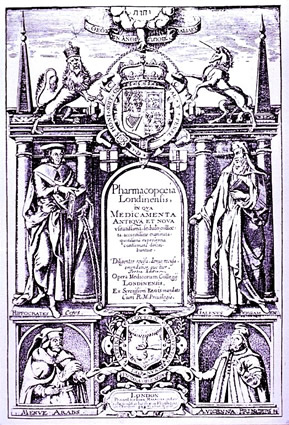

The first edition had 200 pages containing 680 simples (non-compounded drugs) and 712 compounded drugs5, but "was full of mistakes and carelessly printed. The College quickly withdrew it."6 A second edition, called Pharmacopœia Londinensis, appeared four months later on December 7, 1618, containing 1,190 simples and 963 compounded drugs.7 The medicines included "were largely compiled from existing sources."8

Upon publication, the Pharmacopoeia became the standard for London as well as the whole of England"9 because James I commanded all apothecaries to "follow that and only that official listing of drugs and preparations."10

Pharmacopoeia Londinensis (1627)

A third edition of the Pharmacopoeia was published in 1650 which "differed little from the earlier edition, except for one or two additions and some variations in the prescriptions."11 The fourth edition was printed in 1677 with a few additional formulas, but otherwise not substantially different than the previous version. A fifth edition appeared in 1721.12 This was the last edition of the London Pharmacopeia before the end of the golden age of piracy. In fact, its effect probably didn't reach the golden age sea-surgeons who would have used a previous edition (if they could read them - all the London Pharmacopoeias during this time were published in Latin).

In addition to the Latin versions published in London, a variety of translated versions found their way to other countries. Historian David Cohen explains that "British works, with essentially British titles, were printed in Portugal, Spain, both regions of the Low Countries, Switzerland, Germany, France, Italy, the United States, India, Madagascar, and possibly Austria."13 Cohen further notes that "over two hundred reprints, translations, or redactions [abridged versions] are mentioned in the literature"14. It became a sort of de facto standard around the world and many of the medicines mentioned by period sea surgeons are found in it.

1 D.M. Dunlop, “The History and Development of the “British Pharmacopoeia””, British Medical Journal, Nov. 22, 1958, p. 1250; 2 The British Pharmacopoeia Commission, www.pharmaopoeia.gov.uk, gathered 2/28/15; 3,4 Stuart Anderson, Pharmacopoeias of Great Britain, International Society for the History of Pharmacy, www.histpharm.org, gathered 3/20/15, p. 1; 5 Kremer’s and Urdang’s History of Pharmacy, 4th ed., Edited by Glenn Sonnedecker, p. 430; 6 Anderson, p. 1; 7 Kremer’s and Urdang, p. 430; 8 Betty Jackson, “From Papyri to Pharmacopoeia” From The Evolution of Pharmacy in Britain, Edited by F.N.L. Poynter, 1965, p 156; 9 Anderson, p. 1; 10 Christopher W. Koehler, “Pharmacopoeias”, Modern Drug Discovery, November 2002, p. 54; 11 Anderson, p. 2; 12 Anderson, p. 2; 13,14 David L. Cowen, Pharmacopoeias and Related Literature in Britain and America, 1618-1847, 2001, p. 86

Medicinal Books: The Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia

Like their London brethren, when the Scottish physicians received their charter from Charles I forming the College of Physicians of Edinburgh in 1681, they were allowed to inspect medicines sold within the city and destroy those that were not up to their standards.1 An attempt was made to write by the College to write an Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia beginning in 1683, but according to physician Robert Sibbald, its' publication was "was prevented by

the 'malice' and obstruction of a 'faction'."2

Artist: William Jardine - Sir Robert Sibbald (1838)

Sibbald was deeply involved in the effort. He was elected as the President of the College in 1684 and first professor at the University of University of Edinburgh in 1685.

The faculty of Edinburgh college and the physicians3 began a detailed study of what should be included in their Pharmacopoeia in 1697.4 The first published Edinburg Pharmacopeia - Pharmacopoeia Collegii Regii Medicorum Edinburgensis - appeared in 1699, dedicated to William III.5 While it contained many of the ingredients included in the London Pharmacopoeia, "there were also considerable differences and it is obvious that the compilers exercised considerable individual initiative and judgment."6

The second edition of the Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia was released in 1722, removing some things ‘as not differing from others in virtue; or as having been introduced by superstition or credulity of antiquity’.7 Historian David Cohen reports that the book was divided into three parts, simples (about 50 pages, subdivided into those of vegetable, animal, and mineral origin), compound medicines (about 150 pages subdivided into categories like tinctures, powders, and electuaries) and chemical remedies (about 50 pages).8 Like its London brother, the second edition came out late in the golden age of piracy and would have been less relevant to practising sea surgeons during that time than the first edition.

Many sea surgeons during the early 18th century were likely to have been exposed to the Edinburgh medical system since "the Royal Colleges of Surgeons in Scotland (Edinburgh, Glasgow and Aberdeen) were churning out 80 per cent of Britain’s qualified doctors. The dire lack of positions available at home meant that most were obliged to earn their living beyond their native shores."9 So, provided they could read Latin, they may have had access to the Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia.

1 D.M. Dunlop, “The History and Development of the “British Pharmacopoeia””, British Medical Journal, Nov. 22, 1958, p. 1250; 4 David L. Cowen, "The Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia, Medical History, April, 1957, p. 135, Endnote 1; 3 Dunlop, p. 1250; 4 David L. Cowen, Pharmacopoeias and Related Literature in Britain and America, 1618-1847, 2001, p. 34; 5 Dunlop, p. 1250; 6 Cowen, Pharmacopoeias and Related Literature, p. 34; 7 P. Shaw, The Dispensatory of the Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh, (London, 1727) iv. cited in Cohen, Pharmacopoeias and Related Literature, p. 38; 8 Cowen, Pharmacopoeias and Related Literature, p. 36; 9 Eric J. Graham, Seawolves: Pirates & the Scots, 2005, p. 108