Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Next>>

The Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory, Page 9

Medicinal Books Used in This Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory

The creation of the Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory required reference to a

Tools of the Apothecary, From Jean de

Renou's

Dispensatory Title Page

large number of medicinal books to explain the medicines featured. Certain privately printed dispensatories were more useful than others and were relied upon more often. These include:

Nicholas Culpeper's A Pharmacopoeia Londeniis (1720 Edition)

Jean de Renou's A Medicinal Dispensatory (1657 Edition)

John Pechey’s The Compleat Herbal (1707 Edition)

John Quincy's Pharmacopoeia officinalis & extermporanea: or, A Compleat English Dispensatory (1719 Edition)

Robert James’ Pharmacopia Universalis; or, a New Universal English Dispensatory (1747)

The three sea surgeon's whose material was used to create the Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory incorporate a wide variety of medicines, the details of which are not always easily found. The list of other sources used to find some of the more obscure medicines is quite extensive. The books below were only used when a medicine could not be found in the above sources. They include:

Arnold James Cooley, Cooley's Cyclopedia of Practical Recipts (1872)

Dispensatory of the Royal College of Physicians (1747)

Edinburgh Dispensory, 2nd ed. (1789)

German Physician Michaelis Ettmüller

Michaelis Ettmuller, Opera Omnia (1727) [Translated from Latin]

Leonardo Fioravanti, An exact collection of the choicest and more rare experiments and secrets in physick and chyrurgery (1657)

Samuel Frederick Gray, A Supplement to the Pharmacopeia (1821)

Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie (1597)

Johann Daniel Horstius, Pharmacopeoia Galeno-Chemica, Catholica (1606) [Translated by the author from Latin]

William Lewis, The Pharmacopoeia of the Royal College of Physicians at Edinburgh, Faithfully Translated from the 4th Edition (1748)

Angelo Paglia & Bartholomaeus, In Antidotarium Joannis filii Mesue censura: cum declaratione simplicium medicinariu (1543) [Translated by the author from Latin]

Richard Phillips, Pharmacopoeia of the Royal College of Physicians London (1836)

Pierre Pomet, A Compleat History of Druggs, 3rd Ed. (1737)

James Rennie. A New Supplement to the Pharmacopoeias of London, Edinburgh, Dublin, and Paris (1833)

William Salmon, Pharmacopœia Londinensis: or, The New London Dispensatory (1716)

French Apothecary Joannes Jacob Wecker

Johann Shroeder, D. Johann Schroders Pharmacopoeia Universalis (1748) [Translated by the author from German]

Johann Christoph Sommerhoff, Lexicon pharmaceutico-chymicum, latino-germanicum et germanico-latinum (1701) [Translated by the author from Latin]

Johannes Jacob Wecker, Le Grand Thesor ou Dispensaire et Antidotaire, (1616) [Translated by the author from Old French]

Appendix A found in Joan Druett's book Rough Medicine was also most helpful in identifying some of Woodall's more arcane medicines.

When discussing the books used in making the Dispensatory, we cannot leave out the books written by sea surgeons. It is from these that the list of medicines included in the sea surgeon's dispensatory are taken as well as many of the descriptions of how they worked. These books include:

John Woodall's The Surgions Mate (1617. 1639 & 1655)

Thomas Brugis' Vade Mecum, or A Companion for a Chirurgeon, 7th ed. (1689)

John Moyle's The Sea Chirurgeon (1693)

The first two books have descriptions of a variety of medicines which were used at sea and the last contains a list of medicines suggested to be taken to sea with some basic descriptions.

A final document of interest is apothecary John Tweedy's 1743 "Bill for Medicines" made up for the surgeon and crew of the Rhode Island-based privateering ship Revenge. While not a book, the items in Tweedy's list are part of the Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory because they were used on a privateering ship close to the period of interest. Let's look at the works of the primary dispensatories used as well as those written by the sea surgeon in greater detail.

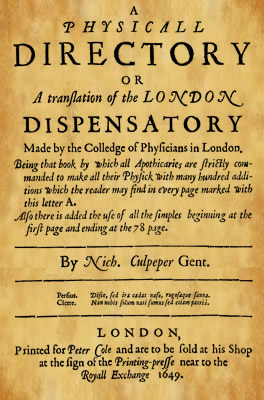

Medicinal Books Used: Nicholas Culpeper’s A Physical Directory (1649)/Pharmacopoeia Londoniis (1720)

Culpeper's A Physical Directory (1649)

Probably the best known privately-printed dispensatory was Nicholas Culpeper's unauthorized translation of the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis, which was first printed in 1649 as A Physical Directory and expanded in 1653 in the English Physitian and in 1720 as Pharmacopoeia Londiniis.

It has basically been in print ever since, being constantly adapted and revised over the centuries. It was popular because it was in English, "was cheap, having no need of illustrations of the common or garden English herbs that were well known to its audience, and it showed a simple and safe alternative to the heroic chemical medicines which were in vogue in the 18th and 19th centuries.”1

Culpeper's book contains explanations of simple, compound and chemical medicines, examining the simples, giving the recipes for compound and chemical methods and then following this information with Culpeper's explanation of how the medicines were to be used. His descriptions tend to be a bit erratic, always telling what the medicine was used for (or sometimes recommending it not be used at all) and sometimes containing information on the humoral properties. Culpeper's descriptions are occasionally entertaining because they contain sarcastic asides. Such comments are primarily directed at the Royal College of Physicians, where he is "critical of the privilege and avarice of the doctors... challenging the monopoly of apothecaries.”2

While much of Culpeper's commentary suggests that he was a Galenist, he still "rejected the authority of old texts in favour of experiment and observation as a means to proper reasoning in physic."3 Historian Doreen Nagy notes that Culpeper "was the most influential and widely published seventeenth-century critic of the monopoly exercised by the medical profession."4 Yet, while he pointed out the things he thought wrong or harmful in the Pharmacopoeia, he also praised those which thought worked well.5

Nicholas Culpeper (1655)

Culpeper was born in October of 1616, probably in Ockley, Surrey. His father Nicholas, rector of Ockley died shortly after his birth. His mother Mary took him to live with her father, the rector of St. Margaret's of Isfield, "where he grew up learning the names of the plants of the surrounding Sussex fields and hedgerows."6 He attended a free-school, moving on to Cambridge University in 1632. He left Cambridge in 1634 to elope, but his intended was struck by lightning and killed on the way to meet him. Culpeper did not return to school, but was apprenticed to Mr. White, a London apothecary. A year later, White's business failed so Culpeper apprenticed himself to Francis Drake (no, not that one) of Threadneedle Street.

When Drake died in 1639, Culpeper went into business with Drake's other apprentice, Samuel Leadbetter. Culpeper was accused and acquitted of witchcraft in 1642 and again in 1643 and Leadbetter was ordered to remove him from his shop, although Culpeper did not leave Leadbetter until 1644. In 1640 he married 15 year old Alice Field and, through Alice, was able to assemble enough money to "set himself up as a physician in poor and unfashionable Spitalfields, East London, where he remained until the end of his life, treating the poor and the uneducated."7

Culpeper published a variety of books, most aimed at educating the common folk in medical practice. He wrote several books on the astrological aspects of medicine and included material in his dispensatory on when to gather and administer various medicines based on the astrological signs. Nicholas Culpeper died in 1654 of consumption, possibly brought on by a musket shot he had received in the chest while fighting at the battle of Newbury. "[P]robably no author acquired so formidable and scandalous a reputation as Nicholas Culpeper, apothecary, astrologer and 'physician'."8

1 Graeme Tobyn, “Nicholas Culpeper’s Herbal Therapeutics”, Journal of the American Herbalists Guild, Spring/Summer 2002, p. 19; 2,3 Graeme Tobyn, Alison Denham and Margaret Whitelegg, “Nicholas Culpeper”, The Western Herbal Tradition, 2010, not paginated; 4 Doreen G. Nagy, Popular Medicine in Seventeenth Century England, 1988, p. 25; 5 L.G. Matthews, “Herbals and Formularies”, From The Evolution of Pharmacy in Britain, Edited by F.N.L. Poynter, 1965, p. 199; 6,7 Tobyn, Denham and Whitelegg; 8 Matthews, p. 199

Medicinal Books Used: Jean de Renou’s A Medicinal Dispensatory (1657)

Jean de Renou's 1608 book Dispensatorum Medicum Contenins Institutionum Pharmacueticorum was translated from the original Latin and published in English in 1657.1 "Judging by the no less that five high quality, folio sized parallel editions, it seems that the English translation was

Jean de Renou from Wellcome Collection (1608)

expected to be a commercial success, particularly among apothecaries."2 Given the timing, it is likely that this translation was intended to capitalize on the success of Culpeper's dispensatory which had gone through several printings by then.

In his letter to the reader, translator Richard Tomlinson says that in Renou's book "the whole Pharmaceutical Art is denuded and redacted to the clear intelligence of the meanest capacity, claiming your attentions, whil'st it affords instructions to conduct you to a clear prospect of Via recta ad vitam longam ['The right way to a long life'], promising a Medicine for every Malady and a Balm for every Soar."3 If that sounds breathlessly wordy and overwrought, Tomlinson goes on to liken Renou to "Phoebus skipping from the Bowers of Neptune, and by his darting through the Casements of Heaven"4 and "plowing through the liquid Intrals of Nureus, dancing the Lovato's upon the azured waves"5. He even recites poetry about the importance of herbs in his introduction.

The part of Renou's book which describes the simples contains nice, brief descriptions of the medicinals with each being in its own chapter, organized into plant, mineral and animal parts. He often specifies where these simples can be found and gives information on the humoral properties of the various medicines. The part of the book on compound medicines (called The Apothecaries Shop) contains an explanation of how the medicine should be prepared followed by Renou's commentary on how the medicine is best used. These commentaries tend to be verbose, often containing asides on how various other writers prepared the medicine and what they thought of them. While these can be interesting, they tend to make Renou's point more difficult to follow. To add to the confusion, interpreter Tomlinson favors arcane and unusual words, many of which are hard to interpret. Where Tomlinson's translation of Renou's work is used in the Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory, you will find a lot of necessary explanatory notes in brackets.

Not much is said about Jean de Renou himself. He was born around 1568 in Coutances, France. Renou studied and graduated in Paris in 15986, becoming the Royal Councillor and Chief Physician7 to French king Henry III.8 Renou died around 1620. His writings focused on pharmacy and were popular enough to see multiple printings. His works were translated from Latin into his native French by Louis de Serres in 16169, "who places him above all his predecessors in the same walk."10 Several German editions of the Dispensatorium also appeared: Frankfurt in 1609 & 1615 and Hanau in 1631.

1 Andrew Wear, Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680, p. 65; 2 Jukka Tyrkkö, "A Physical Dictionary (1657): The First English Medical Dictionary" Selected Proceedings of the 2008 Symposium on New Approaches in English Historical Lexis, T.W. McConchie, ed., p. 174; 3,4,5 Richard Tomlinson, "To the Reader", Jean de Renou's A Medicinal Dispensatory, not paginated; 6 Louis Mayeul Chaudon, Universal Dictionary, historical, critical and bibliographical, Volume 14, Translated out of the original French by the author, p. 46; 7 David Aubri Hanau, Frontispice. Halfvellum., A pasted page with some bibliographical notes - “Dispensatorium Galeno Chymicum Continens by Renou”, 1631, ZBav.com, gathered 5/2/15; 8 C.J. Duffin, A History of Geology and Medicine, p. 94; 9 Eugène-Humbert Guitard, Histoire sommaire de la littérature pharmaceutique. Conférences-Leçons à l'usage de MM. les Etudiants en Pharmacie. 3e Conférence : Les traités de pharmacie privés au XVIe et XVIIe siècles, Vol. 24, Issue 94, 1936, p. 299; 10 David Aubri Hanau, gathered 5/2/15

Medicinal Books Used: John Pechey’s The Compleat Herbal (1695)

Physician John Pechey's The Complete Herbal appeared in 1694 with a second edition following in 1707 containing "the addition of many physical herbs, and their vertues."1 As a herbal

Pechey's The Complete Herbal (1707)

(rather than a dispensatory), it focuses on descriptions of simples - the basic plants and their constituent parts. Being a physician, Pechey also includes quite a bit of information on the compound medicines inside of his explanation of the simples.

In his preface, Pechey says that his work is based on the work of English naturalist John Ray who published several books on plants in the late 17th century, as well as medicines "collected from the best Authors; many of which I have found by Experience very useful."2

Pechey's book divides the topic into local and foreign herbs. In the first section, titled 'The English Herbal' (196 pages in the second edition), Pechey says he "only describ'd such Plants as grow in England, and are not commonly known; for I thought it needless to trouble the Reader with the Description of those that every Woman knows; or keeps in her Garden."3 In the second section, called 'The Exotic or Foreign Physical Plants' (152 pages in the second edition), Pechey provides "no Descriptions of the Herbs, or Trees; for I account it unnecessary to describe the Form or Shape of that, which most of us are never likely to see."4 He notes that he instead focuses on particular parts of exotic plants such as the "Gums, Balsam, Juices and the like" because those are the parts that English apothecaries were most likely to find in their shops.

Pechey's book includes interesting descriptions of simples, noting the medicinal properties of each part of plants (such as seeds, fruits, leaves and roots.) For the English plants, he lists what they are good for, what they look like, when and where the plant can be found and sometimes includes information on their humoral properties, although this is not always complete. True to his comments in the Preface, the section on foreign plants focuses on what they are used for and what compound medicines they are included in. If he knows their country of origin, he helpfully notes that as well.

Pechey was born in Chinchester in 1655.

Artist: William Hogarth

Cheapside, London in the 17th Century (1745)

From Restoration Procession of Charles II at Cheapside

He graduated from Oxford with a Master of Arts in 1678 and was admitted to the College of Physicians in December of 1684. In 1687, he took a five year lease on part of a house in Cheapside known as The Golden Angel and Crown with two other physicians "where they collected a stock of drugs and saw patients by turns."5 When the lease ran out in 1692, he moved the Angel and Crown to Basing Lane. He appears to have spent most of his living in and around Cheapside.6

"His methods were those of an apothecary rather than of a physician"7. He printed a variety of other books during his lifetime, including several on chronic diseases, The London Dispensatory in 1694, A General Treatise of the Diseases of Maids, Big-bellied Women, Childbed Women, and Widows in 1696 and a translation of the whole works of Physician Thomas Sydenham in 1695.

Like Culpeper, Pechey was a proponent of making medicinal information available to the common man. He explains in The London Dispensatory that he had "for several years endeavoured to render the Art of Physick as plain and easie as the nature of it would allow; by separating practice and experience from the vain fictions of a sort of men, whose business it is, to make every part of it obscure and misterious."8

1 John Pechey, The Compleat Herbal of Physical Plants, 1707, title page; 2,3,4 Pechey,"Preface", not paginated; 5,6 Harold J. Cook, ‘Pechey, John (bap. 1654, d. 1718)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004;7 Norman Moore, “Quincy, John”, Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Vol. 44, p. 184; 8 John Pechey, The London Dispensatory, 1694, Preface

Medicinal Books Used: John Quincy’s Pharmacopoeia officinalis & extemporanea: or, A Compleat English Dispensatory (1718)

Quincy's English Dispensatory (1719)

John Quincy's Pharmacopoeia officinalis & extermporanea: or, A Compleat English Dispensatory, first printed in 1718 was one of the most popular dispensatories on this list; it had gone into 10 printings by 1736.1 Quincy's text is clearly written by a learned man, but one who manages to avoid some of the pretentiousness found in other books from the period. He interprets the material in various books for concocting medicines and his comments are usually brief and to the point. Since Quincy rejected humor theory, he provides little information on the humoral qualities of different medicines. He admits that his book is based on "the Authors of best Note in either of the Pharmacies, of every Country and Language"2.

The Dictionary of National Biography notes that his book "contains a complete account of the materia medica and of therapeutics, and many of the prescriptions contained in it were long popular."3 In the second edition, printed in 1719, Quincy himself confesses that "it would he difficult not to express some Satisfaction at the good Reception of the former Edition amongst the most disinterested judges, and the quick Run of that whole lmpression."4

Anatomy Theater, College of Physicians

From Quincy's English Dispensatory (1721)

His book is divided into four sections with the first concerning the theory of pharmacy, the second discussing simple medicines and their preparations, the third explaining 'Officinal' compound medicines [officinal meaning they were found in the apothecary shops] and the last containing "Examples for Extemporaneous Prescriptions, wherein we have been guided more by the present Practice, than by any Authors yet [made] publick"5. 'Extemporaneous' comes from the Latin 'ex tempore' ("at the time"), meaning that it is a medicine given on the spot for a specific patient with a specific ailment. This section basically contains a list of health issues with a variety of suggested prescriptions to treat each one.

Quincy's date of birth is unknown. He was apprenticed to an apothecary, practiced medicine as an apothecary in London.6 He studied mathematics and the philosophy of Sir Isaac Newton, receiving a Medical Doctorate from the University of Edinburgh with the publication of his Medicina Statica Britannica, a translation of the ‘Aphorisms’ of Sanctorius in 1712.7

He wrote or translated 11 works in all, the most famous of which were his Dispensatory and his medical dictionary Lexicon Physico-medicum, which first appeared in 1719.8 In The Western Herbal Tradition: 2000 years of medicinal plant knowledge, the authors note that even Quincy's death is "dated by his publications and is reckoned to be in 1722.”9

1 Kremer’s and Urdang’s History of Pharmacy, 4th ed., Edited by Glenn Sonnedecker, p. 430; 2 John Quincy, "The Preface", Pharmacopoeia Officinalis & Extemporanea, 1707. p. viii; 3 Norman Moore, “Quincy, John”, Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Vol. 47, p. 112; 4 John Quincy, "The Preface", p. xii; 5 John Quincy, "The Preface", p. x; 6 Norman Moore, “Quincy, John”, Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Vol. 47, p. 112; 7 Norman Moore, p. 113;, 8,9 Graeme Tobyn, Alison Denham and Margaret Whitelegg,"John Quincy", The Western Herbal Tradition: 2000 years of medicinal plant knowledge, 2010, not paginated

Medicinal Books Used: Robert James’ Pharmacopia Universalis; or, a New Universal English Dispensatory (1747)

The last Dispensatory we will discuss in detail is Robert James Pharmacopia Universalis; or, a

Robert James' Pharmacopoeia Universalis (1747)

New Universal English Dispensatory, first published in 1747 and reprinted in 1752 and 1764, with a Venetian translation, Nuova Farmacopeia Universale, being released in 1758.

James' Dispensatory provides the multiple names given to each medicinal plant in Latin as well as the book which was the source of each name. (The naming of plants was still in flux at this time. It didn't truly begin being systemized until after the golden age of piracy in 1753, when Carl Linnaeus published his book Species Plantarum.1) James' book is one of the best for determining when the simple plants should be harvested, which parts should be used and what they should be used for. He occasionally indulges in historical asides on who did what with some of the medicines, usually tying the stories back into why and how the medicine operates.

James was not a fan of overly complex compounded medicines, sniffily noting that in previous decades it was "the Custom for the Writers of Dispensatories to embarrass their Compositions, and for Physicians to overload their Prescriptions, with a great Number of superfluous Ingredients; and hence the Efficacy of Medicines was render'd less certain, and the Practice of Physic more precarious."2

He explains that "for the last twenty or thirty Years" the best physicians had worked "to prune away the Branches of Physic which bear no Fruit; and to restore the Art to that useful Simplicity... [which] has induced a very Considerable Change in the Modes of Practice"3. Since his book was published in 1747, he was talking about changes that had taken place near the end of the golden age of piracy.

Dr. Robert James, From his Medical Dictionary (1743 )

As his previous comments suggest, he is a fan of simpler medicines. He felt the official pharmacopoeias of London and Edinburgh should eliminate more of "their Medicines, whose Composition, notwithstanding their Antiquity, render them extremely ridiculous; such I mean, as in the Quantity commonly given for a Dose, contain the Fraction of a Grain of some Ingredient, which alone might be taken in the Quantity of half an Ounce, without any considerable Effect."4 He suggested that it would be better to give larger doses of simpler medicines.5

Robert James was born in 1703 in Kinvaston, Staffordshire. He went to grammar school in Lichfield and then attended St. John's College, Oxford, where he received a Bachelor of Arts in 1726. "He was admitted an Extra-Licentiate of the College of Physicians 12th January, 1727-8, and the 8th May of the same year was created doctor of medicine at Cambridge, by royal mandate."6 James was licensed by the Royal College in 1765.

He practiced as a physician in various places including Sheffield, Lichfield, and Birmingham before finally coming to London around 1740. "To make his name known in the medical profession and to attract patients, he turned to publishing A New Method of Preventing and Curing the Madness Caused by the Bite of a Mad Dog (1741)"7. He continued to write, publishing a variety of books on medicine, the most famous of which was his Medical Dictionary, published between 1743 and 1745. It was quickly translated into French, retaining its popularity for over a century.8

James was also famous for inventing Dr. James Fever Powder, which contained arsenic and calcium phosphate, although "it was never proven effective for treating any particular disorder."9 When he patented the powder, he was condemned for "falsifying their specification", which tarnished his otherwise sterling reputation.10 He died in 1776.

1 Usually these names are similar enough to figure out. For example Kaolin earth is variously called Bolus Vera Orientalis, Bolus Veræ, Bolus Verus and Bol. Ver. However this is not always the case. Potasium sulfate is variously referred to as Sal de duobus, Pulvis Archeticus Paracelsi, specificum purgans and even simply 'the emetic.' For a brief overview of the history of plant naming, see History of plant systematics on wikipedia; 2,3 Robert James, "Preface", Pharmacopœia universalis, p. v; 4 James, "Preface", p. vii; 5 James, "Preface", p. viii; 6 William Munk, G. H. Brown, 7 O. M. Brack and Thomas Kaminstki "Johnson, James, and the Medicinal Dictionary", Modern Philology, May, 1884, p 378; 8 "Robert James (physician)", wikipedia, gathered 5/9/15; 9 "Robert James", The Roll of the Royal College of Physicians of London: 1701 to 1800, 1878, p. 269; "Dr James’s Fever Powder" Segen's Medical Dictionary, 2011, gathered 5/9/15; 10 Munk & Brown, p. 269