Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Next>>

The Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory, Page 4

Medicine Use: Chemical Medicines

Even though the Paracelsian and Galenic theories were debated by physicians in the late 17th century, the chemical medicines promoted by Paracelsus were increasingly adopted into medicine. Note that 'chemical' medicines at this time referred primarily to "processes employing the

A Variety of Distillation Processes, from Buch der Rechten Kunst

zü Distilieren die Eintzigen Ding, by Hieronymus Brunschwig (1500) use of fire and particularly of distillation"1, not the complex chemical processes of which we are familiar.

Historian George Urdang explains that "production of so-called 'essential' [purer] forms from crude drugs was implied in the designation chemical, whether this was accomplished by separating the finer parts from the grosser parts by distillation or by boiling down the mother liquid concerned and allowing crystallization. In like manner the 'essential,' even 'quintessential' parts were obtained by extraction, whether the product be termed a tincture or extract."2

This gradual co-option of part of the Paracelsian (and Helmontian) doctrine did not go unnoticed. In his book Galeno-pale, Helmontian physician George Thomson complained that the Galenists took a "supplanting course, and of a sudden will all become Chymists; but Galeno-Chymists, as monstrous and Anomalous as a Centaure or Syren"3. Regardless, the chemical medicines were taken into the medicinal orthodoxy without much of the supporting theory. As a result, "it became increasingly important for the pharmacist to become a skilled chemist. Pharmacy shops came to have chemical laboratories associated with them, containing equipment for distillation and other procedures needed to produce chemical remedies."4

In fairness, Paracelsus did not actually discover the chemical medicines. Urdang explains that the Augsburg Enchiridion of 1564 contained a variety of chemical preparations that predate Paracelsus: Aqua fortis [nitric acid], Aqua cum Mercurio, and Lac Virgineum. It also gave receipts for oils of turpentine and juniper and a series of volatile oils including oil of vitriol and sulfuric acid, all of which were obtained by distillation.5 So there was a non-Paracelsian origin for many chemical remedies.

Using chemical processes to create medicines meant that distillers "gradually specialised and became known as chemists; as chemical medicines became more popular in the

French Pharmacist/Chemist Nicholas Lémery latter part of the seventeenth century, these men often combined manufacture and wholesale with some direct retailing."6 Historian Betty Jackson notes, "One of the main contributions to this progress was the development of organic and analytical chemistry. Most of the early chemists were either apothecaries or physicians and it was natural, therefore, that they should direct their investigations towards the analysis of crude drugs. Among these early pioneers was the French apothecary Nicolas Lemery (1645- 1715) who has been described as the founder of plant chemistry."7

The popularity of such chemical remedies can be seen looking through the contents of the books from the time period. The 1677 Pharmacopoeia Collegii Regalis Londini (the 4th edition of the London Pharmacopoeia in use throughout most of the golden age of piracy) contains 37 distilled oils and waters8 and 32 chemically prepared medicines such as sublimates, precipitates, tinctures, spirits and extracts.9 Nicholas Culpeper's 1720 Pharmacopoeia Londonensis (a reprint of Culpeper's 1653 edition, which was most likely based primarily on the 2nd edition of the London Pharmacopoeia printed in 1618) contains 23 oils and "Chymical Oyls", 21 "Chymical Preparations" and 2 salt extracts.10

Chemically-prepared medicines also had a place in the medicine chests of our sea surgeons as we shall see. However, caution was still advised. In his poem 'In praise of Sulphur or Brimstone' sea-surgeon John Woodall warns,

But Chimicke [chemical] medicines are to fooles

like swords in mad mans hands,

When they should aide, oft times do kill,

such hazards in them stands.Let Surgeons mates to whom I write,

be warn’d by me their friend,

And not too rashly give a Dose,

which then‘s too late to mend.For many a good man leaves his life,

through errours of that kinde,

Which I with young men would avoid

and beare my words in minde.Though Sulphur, Sal, and Mercurie

have healing medicines store,

Yet know the’ have poyson and can kill,

prepare them well therefore.11

1 Kremers and Urdang’s History of Pharmacy, 4th ed., Edited by Glenn Sonnedecker, p. 104; 2 George Urdang, "How Chemicals Entered the Official Pharmacopoeias", Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, Vol. XXXIX (1947-1949), Banner Bill Morgan, ed., p. 116; 3 George Thomson, reprinted in Health, Disease and Society in Europe, 1500-1800: A Sourcebook, edited by Peter Elmer, Ole Peter Grell, 2007, p. 135; 4 Kremers and Urdang, p. 354; 5 Urdang, p. 116; 6 R.S. Roberts, "The Early History of the Import of Drugs into Britain", From The Evolution of Pharmacy in Britain, Edited by F.N.L. Poynter, 1965, p. 172; 7 Betty Jackson, "From Papyri to Pharmacopoeia" From The Evolution of Pharmacy in Britain, Edited by F.N.L. Poynter, 1965, p 156; 8 Based on the author's calculations, taken from Pharmacopoeia Collegii Regalis Londini, p. 182-8; 9 Based on the author's calculations, taken from Pharmacopoeia Collegii Regalis Londini, p. 189-97; 10 Nicholas Culpeper, Pharmacopœia Londinesis, 1720, Index; 11 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 296

Medicine Use: Efficacy

A Physician's Expectation of Medicine, From Ars Sanadi,

Georg Ernst Stahl, (1730)

It is natural for a patient to wonder how well his medicines are working. Even today in our era of rigorous medical testing and double blind studies people evaluate the efficacy of their medicines by how well they feel the medicine is working for them. (Sometimes unfairly, given that the value of many medicines today rely on the entire prescription being taken, not on what the patient decides based on how they feel a few days into the regime.) Human nature being what it is, period authors debated the efficacy of medicines just as we do today - and not without reason.

Although official pharmacopoeias helped standardize medicinal recipes, they were unable to turn fully away from folk remedies. A plethora of questionable folk medicines, many of which appear to have had their origins in the middle ages1, were still a part of medicine during the golden age of piracy.

These folk remedies were employed and encouraged both by scurrilous quacks and some 'legitimate' physicians,

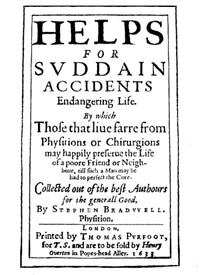

resulting in many being included in the period medicine books. Physician Stephen Bradwell's 1633 Helps For Suddain Accidents Endangering Life, often considered the prototype for the home-based first aid manuals, contained a variety of such medicines.

For example, his list of cures for poisoning included:

The Hoofe of an Oxe cut into parings, and boyled with bruised Mustard-seed in white Wine and faire Water [clean, pure water].

The Bloud of a Malard drunke fresh and warme: or els dryed to powder, and so drunke in a draught of white Wine.

The Bloud of a Stagge also in the same manner.

...

There is also another excellent course to be taken (besides all these) by those of abilitie, and that is; Take a sound horse, open his belly alive, take out all his entrayles quickly, and put the poysoned partie naked into it, all save his head, while the body of the horse retaines his naturall heate: and there let him swett well.2

Although the gutting of a horse seems a bit over-the-top, even the London Pharmacopoeia of 1678 included similar simples in their lists including: the blood of doves, goats and turtles; the fat of eels, serpents and men; the teeth of boars, elephants and sea-horses (!); the intestines

Ambroise Paré

of foxes and wolves; the penises of deer and bulls and the skull of a man killed violently.3

It appears that surgeons and physicians of the time, while skeptical of folk remedies, were also afraid to dismiss them entirely in case they actually worked. Famed French military surgeon Ambroise Paré commented loftily, "oft times there is no small superstition in things that are outwardly applied."4 He proceeds to list eleven fantastic remedies for various illness. These include: curing coughs by spitting in to the mouth of a toad, helping headaches by placing the noose used to hang a man around your temples and eliminating a toothache by scarifying (making small incisions in) the gums "with the tooth of one that died a violent death"5. While Paré suggests these things are absurd, referring to them as "superstitious fictions"6, he provides extensive detail, hinting even he may have tried some of them. Even our Sea Surgeon's Dispensatory contains a few folk-based items, as we shall see.

Another problem with medical efficacy involved the standardization of ingredients. Pharmacopoeias helped to standardize the amount of each ingredient included in compound medicines, but the

Herbes de Provence marché de Pertuis

concentration of the ingredients themselves wasn't measured. Betty Jackson explains, "No new methods of standardisation were developed in spite of the fact that many of the drugs appearing on the market were adulterated or of poor quality."7 The newly developing field of chemistry combined with the physicians' limited

understanding of how the human body worked limited the ability to understand proper medicine concentration and dosing. As a result, "there developed a speculative, rational approach that was to have an impact on medicine, and on pharmacy, until well into the twentieth century."8 Most physicians relied on personal experience, basing recommendations on what had worked for them in the past.

A slightly more scientific method did exist for measuring medicine efficiency, although its results were likely questionable as well since it was still based on trial and error. Simple medicines (those closest to the medicinal element in its 'raw' state) were felt to be "the gold standard against which all other kinds of remedies were judged. Simples as God-given incorporated notions of primal purity, yet their curative effectiveness depended, paradoxically, on their potential to harm the body."9

Artist: Isaac Cruikshank

Taking Physic (Medicine) (1801)

This capability to destroy as well as heal without a way to measure a medicine's strength also impacted the efficacy of medicines. Seventeenth century physician James Primrose explained that "all remedies have in them a nature in some measure contrary to our body, because they alter it, otherwise they were not remedies and so they may also do harm."10 His solution was to recommend that it would be better "if many both men and women did take Physick [medicines] more sparingly, for they prejudice their health, and that are ever and anon taking Physick, doe seeme almost alwayes to have need of it."11

This last comment points to another possible explanation for the effectiveness of some medicines from this era: the placebo response. This results in a patient responding positively to treatment, even though the medicine may not actually be effective. "The placebo effect is part of the human potential to react positively to a healer. A patient's distress may be relieved by something for which there is little medical basis."12 Since the placebo response wasn't really discussed in medicine until the early 19th century13, a golden age of piracy physician would likely have ascribed the effectiveness of such a medicine as an occult quality such as physician Jean de Renou did in his 1657 book A Medicinal Dispensatory.14

Photo: Forest & Kim Starr

Foreign Remedy Guiacum Offinale

A third problem with medical efficacy involved where they came from. While foreign were new and exotic, they also provided opportunities for substitution of inferior ingredients which could fool unfamiliar buyers. Those who imported medicines, "had to depend on the appearance, taste and smell of the commodity and it is not surprising that a number of adulterated materials escaped, detection, particularly among powdered drugs."15

Last was the problem of just how useful the medicines actually were. Before the golden age of piracy, medical schools "shared with the lay public the belief that herbs were curative, albeit they might assert that their knowledge of them was best or that they could improve them further. Until the late seventeenth century, when [physician Thomas] Sydenham voiced some skepticism, it seems that everyone agreed that remedies worked, though which ones was a matter for debate."16

Still, we know today that many of these remedies were of limited value in treating illnesses. When discussing remedies, R.S. Roberts points out:

Most of these [foreign] drugs like guaiacum really had no therapeutic value, but some such as cinchona and nux vomica were useful additions to pharmacy. The popularity of the useless exotics, however, must not be dismissed merely as a sign of seventeenth-century credulity. Rather it was the result of a new attitude to disease which rejected the fatalism of the past and insisted that some attempt be made to cure every disease. From experience of these drugs there developed in the eighteenth century a more selective, and ultimately a scientific, approach to the use of medicaments.17

1 For many examples, see the 10th century Leechdoms, wortcunning, and starcraft of early England, Vol. II (Bald's Leechbook), edited by Rev. Oswald Cockayne; 2 Stephen Bradwell, Helps For Suddain Accidents Endangering Life, p. 17; 3 Royal College of Physicians of London, Pharmacopoeia Collegii Regalis Londini, pp. 15-7; 4,5,6 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p.585; 7 Betty Jackson, "From Papyri to Pharmacopoeia" From The Evolution of Pharmacy in Britain, Edited by F.N.L. Poynter, 1965, p 155; 8 David L. Cowen, Pharmacy An Illustrated History, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 1990, p. 102; 9 Andrew Wear, Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680, p. 49; 10 James Primrose, Popular Errours or the Errours of the People in Physick, p. 232; 11 Primrose, p. 232-3; 12 "Definition of Placebo Effect", MedicineNet.com, gathered 4/12/15; 13 A J de Craen, T J Kaptchuk, J G Tijssen, and J Kleijnen, "Placebos and placebo effects in medicine: historical overview", Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 1999 Oct; 92(10), p. 511; 14 Jean de Renou, A Medicinal Dispensatory, p. 12;15 Betty Jackson, "From Papyri to Pharmacopoeia" From The Evolution of Pharmacy in Britain, Edited by F.N.L. Poynter, 1965, p 156; 16 Andrew Wear, Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680, p. 49; 17 R.S. Roberts, "The Early History of the Import of Drugs into Britain", From The Evolution of Pharmacy in Britain, Edited by F.N.L. Poynter, 1965, p. 171