The Pirate Surgeon's Quarters: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Next>>

The Pirate Surgeon's Quarters in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 6

Pirate Vessels: Large or Small?

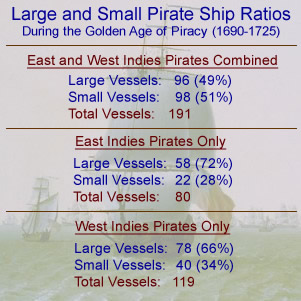

So which did pirates prefer - large vessels or small ones? In the simplest possible terms, the data suggests no preference. Ignoring the fact that there is some overlap in physical ships because that data includes the same ship more than once if she had different captains or commanders at different times, there are 96 large ships (49%) in the sample and 98 small ships (51%).

Pirate Ship Sizes by Area, Graphic: Francis Swain, An East

Indiaman and Other Ships, (c. 1780)

Based on this data, small pirate ships have a miniscule edge over large pirate ships during the golden age of piracy. However, this simple calculation ignores two very important factors in deciding what type of ship is preferred: location and fleet size.

European pirate ships were primarily active in two locations during the golden age of piracy: the East Indies (basically the Indian Ocean) and the West Indies (which, for our purposes, includes the Caribbean and the New England coast). When the data is sorted along these lines, the ratio of small vessels to large changes quite dramatically. In the East Indies, 28% of the vessels in the data are small and 72% are large. In the West Indies, 66% of the vessels are small and 34% are large. Although ratio of ships found in the two area are not precisely opposite, they are pretty close, highlighting the general size difference of pirate ships found in the West and East Indies.

Before continuing, a few notes about the data used is necessary. First, there were also seven captain/ship combinations who were active in both the East and West Indies. They have been counted in both categories: John Halsey's ship Charles1, Samuel Burgess' ship not named in the data2, Joseph Bradish's Adventure of London3, Henry Every's Fancy4, John Halsey's Greyhound5 and John James' two ships Alexander6 and another ship not named.7 Second, two pirate ships were active only in the Atlantic Ocean off Europe and they have not been included in this data because they don't technically belong: Philip Roche's George/Mary/St. Peter8 and John Gow in the Revenge9. (Roche's vessel is barely a pirate to begin with, having only changed the name and details of his ship to escape detection after the crew mutinied.)

This differences between the percentage of ships found in the East versus the West Indies existed because the types of ships used by merchants in the respective areas differed. Historian Ed Fox explains:

Artist: Francis Swaine - East Indiaman off Fort St. David, India (c. 1763)

In the Americas, where both the most common vessel available to pirates and the most common vessel used by their victims was the sloop, it makes sense to find a lot of sloops. In an area where there are a lot of shoals and narrow inlets, sloops make sense, especially as part of a larger squadron. To catch a sloop, the best vessel to use is a sloop. But if we cross the Atlantic we find sloops in general were a lot less common, and the most common vessels attacked by pirate there were slavers and Indiamen on their way East. Sloops and other smaller vessels would be seriously outgunned by their prey, and unsurprisingly we find pirates adopting larger and better armed ships, both because they were more readily available and because they were better suited to hunting the common prey in the region.10

This is one reason there was such a marked difference in the ratios of ships between the two areas.

Another factor which affected the ship ratios has to do with the size of a fleet which a pirate commodore maintained. In the case of lone pirates, they would generally (all other things being equal) have preferred the type of ship that would give them size and space to mount a sufficient number of guns to outclass their merchant victims as well as to hold a large enough number of men. Superior force gave the pirate flag an aura of power. Most merchant vessels tended to keep a small crew, just enough men to make running their ship possible. Knowing this, pirates tried to maintain a large number of men which intimidated the smaller merchant crews. All these extra pirates would need space to eat, sleep and put their belongings, so their vessel had to be large enough to accommodate this. This is also why pirates often forced men who were unwilling to formally join their crew to remain on board. Even if the forced men weren't inclined to fight well (if at all) during an attack, their mere presence gave the pirates the image of having a superior force.

Another way to intimidate prey was for pirates to form fleets of multiple ships. As already noted, the optimal arrangement for such a fleet included a large, typically slow-sailing command ship and one

Howell Davis, From Charles Johnson's The

General

History of the

Pirates (1728)

or more smaller, faster vessels which could be sent to chase and engage a target while the slower, more powerful ship caught up and helped finish the capture. This is why it is difficult to consider the number of smaller pirate vessels as standalone vessels; they were often just part of a fleet which included larger vessels.

An example of importance of a pirate's flag, superior numbers of men and guns may be helpful. After pirate captain Howell Davis mutinied the men aboard the merchant sloop Buck and taken a small vessel of 12 guns, he spotted a French ship of 24 guns and 60 men which he told his fellow mutineers "would be a rare Ship for their Use". Based on their small sloop size and insufficient manpower (35 men), the Davis' crew "looked upon it to be an extravagant Attempt, and discovered no fondness for it"11. However, Davis "assured them he had a Stratagem in his Head [that] would make them all safe"12. Trusting in their Captain, the pirates decided to chase this prize of superior force, starting with the display of their most potent weapon - their pirate flag (in this case, a makeshift one - a dirty tarpaulin they found) - hoisted to provoke fear in the French crew.

Unfortunately, the French ship was not impressed by Davis' pirates or their dirty tarpaulin. However, Davis explained that he was just there to fight them until his consort arrived. Because Davis was in such a small vessel, past experience would suggest that this imaginary second ship must be a larger, slower ship with more men and better armament. To prod the French into surrender, Davis noted that his consort would be "able to deal with them, and that if they did not strike [their flag, meaning they surrendered] to him, they should have bad Quarters"13. As he came closer to the French ship, Davis "obliged all the Prisoners [from the small prize they had taken] to come upon Deck in white Shirts, to make a Shew of Force"14. The French ship struck her colors. Although it was just a ruse, this shows the power mere idea superior numbers of men and guns, the pirate flag and the threat of a fleet of pirate ships.

Pirate location and fleet size aside, there is still the question of what individual pirates might prefer. Not surprisingly, this depended in part of the pirate A goal of some pirates was to improve their ship and fleet vessels;

Artist: Joseph Nicholls

Blackbeard's Ship, The Queen Anne's Revenge from A General

History of the Pyrates (1736)

many pirates did so during the golden age of piracy. For example, Charles Vane started by capturing a six-gun Barbados sloop which he named Ranger15 and then moved to a captured twelve gun brigantine which he also named Ranger.16 Edward Teach traded ships until he acquired the frigate La Concorde which he famously named the Queen Anne's Revenge.17 Charles Grey suggests that the career of Thomas Howard reveals "the true pirate or buccaneer evolution of the 17th century, for, like their predecessors, Howard and his companions commenced with a native canoe and climbed up by successive captures to a full sized and well armed ship with a numerous company."18 Howard reached the apex of ship adoption with the capture of a 700 ton vessel in the East Indies in 1703. He and John Bowen put 56 guns and 234 men and named her Defiance.19

Another master of trading up was Bart Roberts. During his three year reign of pirating on the Atlantic, he started with the thirty-gun Royal Rover (ship 1), which he inherited when Howell Davis was killed20. Roberts was forced to trade down when Walter Kennedy made off with that ship in October of 1719. He made a sloop of 10 guns his command ship, renaming it the Fortune (ship 2).21 In this sloop, he crossed the Atlantic and made his way to Newfoundland where he captured a Bristol galley - the first of four Royal Fortune command ships - into which he put 16 guns (ship 3).22 With that ship, he was able to capture a 26 gun French ship in Newfoundland, making her the second Royal Fortune (ship 4).23 Moving from there down to the Caribbean, he captured a Dutch Ship off of St. Lucia which became the third Royal Fortune (Ship 5), which he mounted with 36 guns.24 His sixth and final ship was the Royal African Company ship Onslow taken off Sierra Leone, which he kept, giving "to her the Name of the Royal Fortune, and mounted her with 40 Guns"24.

While bigger ships could provide pirates with greater force and the ability to keep more men, there were downsides.

Bart Roberts' Tender Sloop Ranger and Frigate Royal Fortune from

A General

History

of the Pyrates by Captain Charles Johnson (1724)

Larger ships necessarily had greater burden and so drew more of a draft, preventing them from going into shallower water where warships could not go without risk of becoming grounded as we have seen. Because larger ships and needed more crew, they had more people to provide food and water, which at times could be very challenging. And, of course, they were far less agile than smaller craft which made them more difficult to maneuver and less effective during fights.

Larger ships were more difficult to careen, requiring more time and effort to move everything out of the ship so that it could be tipped on it's side so that the growth on the underside could be removed and rotten boards replaced. Edward Low actually lost a large Portuguese ship he had taken when careening her, in small part because she was so big (although mostly because he overestimated how big she actually was and forget a rather important detail). Forced man Phillip Ashton explained, "Low had ordered so many Hands upon the Shrowds and Yards, to throw her Bottom out of the Water, that it threw her Ports, which were open, under Water,and the Water flow’d in with such Freedom that it

Artist: Lieve Verschuier

A Flute Being Careened (late 17th century)

presently overset her when she was upon the Careen, whereby she was left, so that he was reduc’d to his old Scooner, which he called the Fancy"24.

Blackbeard actually chose to trade down near the end of his career. He did so after deciding he had too many men with whom he had to share his loot, abandoning his capital ship Queen Anne's Revenge and escaping with forty of his men in one of her tender sloops.25 He then applied for pardon, "to wait a more favourable Opportunity to play the same Game over again; which he soon after effected, with greater Security to himself, and with much better Prospect of Success"26.

Sometimes it just came down to personal preference. Pirate commander Thomas Anstis actually decided to keep his smaller brigantine Good Fortune even after his crew had captured a larger ship called the Morning Star. Charles Johnson explains, "they mounted the Morning Star with 32 Pieces of Cannon, mann’d her with a 100 Men, and appointed one John Fenn Captain; for the Brigantine being of far less Force, the Morning Star would have fallen to Anstis, as elder Officer, yet he was so in Love with his own Vessel, (she being an excellent Sailor) that he made it his Choice to stay in her, and let Fenn, who was, before, his Gunner, command the great Ship."27

So it is difficult to state whether larger ships were preferable to smaller ones in the pirates' eyes. However, from the surgeon's point of view, it is easy. Although ships were certainly never chosen with the surgeon in mind, surgeons aboard larger vessels would typically be better situated than those aboard smaller ones.

1 Charles Grey, Pirates of the Eastern Seas 1618-1723, 1971, p. 259 & 270-1; 2 The London Journal, Saturday, February 24, 1721; 3 Grey, p. 210-1; 4 John Franklin Jameson, "58. Petition of the East India Company. July, 1696. & 63. Examination of John Dann. August 3, 1696.", Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period – Illustrative Documents, 1923, p. 143-4, 145 &154; 5 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 469-70; 6 London Post with Intelligence Foreign and Domestick, 12-1-99 -12-4, Issue 78, 7 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 488; 8 Ed Fox, "31. Phillip Roche, from The Remembrance of Phillip Roche, 11 April, 1723. HCA 1/55 ff. 36-41", Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 145, 149 & 153; 9 London Journal, 3-13-25, Issue CCXCIV & London Journal, 2-13-25, Issue CCXC; 10 Ed Fox, Authentic Pirate Living History Facebook Group, February 27, 1716, gathered 12/21/18; 11,12,13 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 167; 14 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 168; 15 CSPC America and West Indies, Vol. 30, Item 737; 16 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 606; 17 Fox, "22. David Herriot and Ignatius Pell on Blackbeard and Stede Bonnet, from The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and other Pirates (London, 1719), pp. 44-48", p. 94 & 97; 18 Grey, p. 251; 19 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 461-2; 20 Fox, "32. Thomas Lawrence Jones, from The Examination of Thomas Lawrence Jones, 13 February, 1724. HCA 1/55 ff. 50-52”, p. 156-7; 21 The Tryals of Captain John Rackam, and Other Pirates, 1721, p. 30; 22 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 216; 23 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 216-7; 24 CSPC America and West Indies, Vol. 32, Item 463.iii; 25 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 228-9; 26 Philip Ashton, Ashton’s Memorial of Strange Adventures and Signal Deliverance, 1726, p. 28-9; 27,28 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 75; 29 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 289