The Pirate Surgeon's Quarters: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Next>>

The Pirate Surgeon's Quarters in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 11

Battle Surgery: Preparation

"[In preparing for battle] the chirurgeons [go] in the hold... with their chests and instruments to receive and dress all the hurt men..." (Nathaniel Boteler, Boteler's Dialogues, p. 293)

There was a great deal for the surgeon to do in preparation for a battle. Although he could not readily predict how many men would require doctoring, he had to plan for the worst. Before he could even do that,

Photographer: Peter Isotalo

Model Showing the Decks Being Cleared on the Vasa Warship

however, the orlop deck needed to be cleared to allow room to put the wounded while they were awaiting treatment

or recovering after being operated upon. As has been mentioned, the orlop was a multipurpose location where the men slept, cargo and lines were stored and the men dined. Passenger John Covel beamed, "It was pleasure to see the great alacrity and readinesse, I may say the eagernesse, of our Seamen in preparing for the dispute. All their Hamocks were down in a trice; their chests and lumber turn'd out into the boates, or stived (Editor's footnote 1: packed away, stuffed) by the main chains or elsewhere, out of the way. We had a clear ship in a very little while".1

Sea surgeon John Atkins further explains that in readying the ship for a conflict "the Ollop [Orlop Deck] and Cable Tiers are cleared and spread with Canvas, for receiving your wounded Men, the Cockpit separated [possibly by hanging canvas walls] for Operations and dressing them, whence they are to be removed."2

Preparing Medicines, from Krueterbuch Kunstliche Counterfeytunge

der Baume (1569)

Even after the orlop deck was cleared, there was much for the surgeon and his mates to do to prepare for the influx of wounded during battle. Robert Young, the surgeon aboard the naval ship Ardent in 1797 summarized by explaining "two things are necessary [for performing effectively]. First [getting] the necessary materials – second those materials, being arranged and disposed commodiously so as to be readily come at, and directed with facility to their purpose.'"3

Closer to the golden age of pyracy, Baron Gerard Van Switen wrote in 1758 that "a surgeon of a man of War mould have every thing needful, in a sufficient quantity, always by him in readiness (but more particularly in time of war) placed in some kind of box or drawer by themselves."4 (Van Swieten sounds as if he may be describing the surgeon's plaster box here.) Golden age of piracy sea-surgeon John Moyle advises the surgeon to be sure he is "in a Competent readiness for wounded men when they shall be brought down."5

A Covered Makeshift Surgery Table,

from Schwabes

Mageneoffnung (1635)

The first order of business was to set up the furniture in the operating theater. Moyle tells young surgeons that they should first "See that your Allop, or Platform be laid as even as possible, with a Sail spread smooth upon it; which you must speak to the Commander to Order."6

Van Swieten recommended that the surgeon have "the carpenters to lay a platform for your wounded men; if the cables will not be wanted, in one of the cable tires [tiers], or otherwise in the after-hold, by clearing of all manner of lumber out of the way. On the top of a smooth and even tire cask [presumably a cask containing cables], let there be deals or planks laid close together, over them an old sail, and upon that some seamen's bedding from the purser's store-room... ready made up, and laid one by another to place your wounded men on after they are drest, that they may lie quiet without being disturbed."7

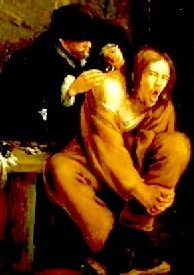

Cockpit Operation on a Table (1820)

Even the sailors dining tables might be spread with a sail and serve as the operating platform on some ships. Samuel Leach reported during a battle that "the long table, round which the officers had sat over many a merry feast, was soon covered with the bleeding forms of maimed and mutilated seamen."8

Moyle also recommends that you "have two Chests to set your wounded Men on to dress them."9 Atkins likewise tells the surgeon to have "two Chests, and a round Stool, to rest your Wounded on for Operation, or Dressing."10 Many operations might br motr easily performed when the patient was sitting as in the image seen below right.

However, surgeon Richard Wiseman dismisses the difference, explaining that, "At Sea they sit or lie, I never took much notice which", although he does add, "where we have convenience to proceed more formally, we always place the Patient to our most advantage, where he may be held firm, and in a clear light, and so that our Assitents may come better about us."11

Artist: Gerrit Lundens

Operation on a Sitting Patient,

from The Surgeon (1649)

Although lighting has already been discussed, Baron Gerard Van Switen mentions it in the context of battle, suggesting that the surgeon have a "number or large candles would be immediately lighted, as soon as the engagement begins, not forgetting to have your mates and assistants properly instructed in what part they are to act"12. Van Swieten's pointed reference to the assistants at the table brings to mind the fact that there were usually many people to hold the wounded down during particularly painful operations, which would also help keep them from knocking over the candles and being burned.

It was also important to some period surgeons to prepare to maintain cleanliness in the operating theater. Moyle suggests "at the Corner of the Platform you are to place two Vessels, one with Water to wash Hands in between each Operation, and to wet your dismembering Bladders in, and for other Services; and the other to throw amputated Limbs into till you have Opportunity to heave them Overboard."13 Van Swieten similarly advises having "a water-cask: full of water near at hand, with one head knocked in, in readiness for dipping out occasionally as it may be wanted"14, presumably for the same purpose. He also suggest the use of an empty bucket "to receive the blood in your operations"15. Some land-based surgeons also used sand16 or sawdust17 in containers under the operating table to help absorb blood, a practice that a sea-surgeon might employ if the materials were at hand.

Photo: Mission

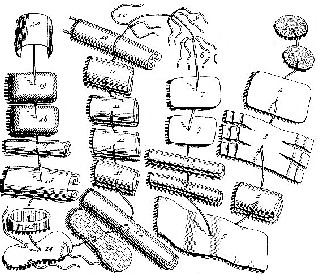

A Sampling of Capital and Other Instruments

Well maintained instruments were also important. Van Swieten recommended that the surgeon's "capital instruments should be constantly kept clean, bright, and in good order."18 Capital instruments were those required for surgeries with high rates of mortality such as amputation, trepanning and repairing other major wounds. Buccaneer surgeon Lionel Wafer explains that he "preserv'd a Box of Instruments... wrapt up in an Oil Cloth"19 to protect them from rust.

In 1755, surgeon Edward Ives recommended "that the naval surgeon should provide himself with six or more amputating knives instead of the two or three usually considered necessary, since there was no time during the heat of the engagement to restore their keenness; and the same reason held good with respect to the number of saws, needles and other instruments for many of these were either lost or mislaid during the noise and confusion."20

As is done in preparation for surgery today, the surgeon's instruments most likely to be required during the chaos of battle were set out in advance. Moyle simply states that the surgeon "must have there in readiness [his] Instruments both large and small"21, suggesting a wide variety of tools be readied. He

An Extensive Set of Surgeon's Pocket Kit Tools: 1) Small Pincers,

2) Bistoury Knife,

3) Double skin retractor, 4 & 5) Scalpels,

6 & 7) Pen Knives,

8 & 9) Retractors?

10) Scissor Forceps,

11) Scalpel with guard,

12) Pen knife, 13) Probe,

14-6) Scalpels

later notes that "your Surgery Chest must not be far from you, least your should have occasion for any thing therein"22.

Atkins says that "when the Ship is preparing for Battle, to arm your Needles, to lay the Apparatus for Amputation particularly, and your Instruments in order"23. He also recommends "round the Stanchion fix some Boards for a Dresser, and covering with a Piece of Bunting, lay your Pocket Instruments"24 in preparation for use.

Every surgeon would carry a pocket kit of instruments for emergencies which would include necessaries like scalpels, scissors, a bistoury knife, retractors, needles and small pincers. Van Swieten also advises setting up a platform - on a barrel "just by (or [a] table) [to] lay all your apparatus [upon], such as your capital instruments, [and] needles"25. He details the preparation of "crooked needles of all sizes, threaded with proper flat ligatures, in proportion to the needle"26.

Dressings Suggested for a Complex Fracture, from A

Description of Bandages and Dressings

by Charles

Gabriel Le Clerc, Figure 43, p. 87 (1701) For a Complete

Description of Their Uses, see the Dressings Article

A large quantity of bandages and dressings would be required for a battle of any significance. The surgeon's assistants and mates were charged with preparing them before the battle so that time wouldn't be wasted on the task when the wounded sailors were being brought below for operations.

John Atkins explains that "in War, the Surgeon always should have Boxes of Dressings ready, Turnikets, some Tents, Pledgets, Buttons [Tow made in the form of a large button], and Dossils, in Sorts a great Number, without being armed [with medicine]; Rowlers [roller bandages], Compresses, Bandages, Ferulæ [ferule - strongly scented gum resin], Laminæ [thin sheets of metal, often copper - used to make a type of splint], of different Sizes"27.

Moyle lists "Linnen, Cross Bolsters [for amputations], Tow, Acetum [a plaster of oil, litharge and copper salts kneaded with hydrocholorine and olive oil], Ova [egg white for wounds], broad Tape to make Ligature, and narrow to bind on Splinters [splints] (for Apparel for Fractures must not now be missing)"28.

Artist: Benjamin Cole

Bart Roberts' Ranger and Royal Fortune Showing Flags, from

A General History of the Pyrates by Charles Johnson (1724)

Van Swieten suggests having "a large quantity of scraped (Short) lint, Some mixed with flour in a bowl [when egg is added to flour-coated bandages, they stiffen]; double and Single headed rollers (or bandages) of all breadths and lengths, in good Store - for Slight wounds and contusions, those made of bunting (the fly-part of an old ensign) will be sufficient"29.

The comment about using the ensign (or a flag) is a curious addition to Van Swieten's list. It may seem unusual, yet in his book John Atkins also recommends that the surgeon "tear up [his] old Ensign for present Use"30. This is likely because the "fly" part of the ensign would be very soft from whipping in the wind and would make for a comfortable dressing.

Van Swieten gives a fascinating amount

A Variety of Pledgets, from Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné

des

sciences,

Volume 2b, Plate 2, p. 104 (1762)

of detail about how pledgets that should be prepared for battle. He advises the surgeon to have "pledgets of tow, of what sizes he pleases; after they are made, they may be wet with water, or oxycrate [an astringent mixture of vinegar and water], on the same board, and dried either by the galley-fire or in the sun. By this means he may the better lay them together (in a drawer or box) without intangling, and they are both much better and readier to spread, when wanted, with any cerate, ointment, or liniment."31

He continues his dressing list, suggesting the surgeon prepare " ligatures strands for tying off arteries], lint, flour in a bowl [perhaps to encourage clotting],... pledgets spread with yellow basilicon, or some other proper digestive [substances to encourage healthy flesh formation, to remove 'bad' humors]; thread, tape, tow, pins, new and old linen cloth, a bucket of water to put your spunges in, … [and] a dry swab or two to dry the platform when necessary"32.

Medicine Preparation, Italian Apothecary (18th century)

Lastly are the medicines to be readied. Moyle orders that "your first intentions [the first medicines you will need in dressing wounds] must now be there ready, with your Restringent Powders, … also [a] Bason; to mix your Restrictives in [both restrictives and restringents are types of medicine to stop bleeding], Pannikins [shallow pans] to warm your Oyls in, and to dissolve your Cerots [pastes], (which can be done over your large Candles) have likewise your Cordial bottle ready at hand to relieve men when they faint."33

The pannikens would probably be held over candles by the surgeons mates or his assistants, who were typically charged with preparing medicines. It is interesting that Moyle recommends reviving those fainted; considering that there was no anesthesia at this time. Many modern people assume fainting would be a welcome respite from a painful battle wound.

Atkins' list of medicines is prepared "That every Thing may be in the best Readiness on your Side for their

Turpentine Collection (1936)

Reception, …mix up a Bason of Astringent [ medicine to contract the body's tissues], and have two or three of your Caps [large round pledgets for amputation] spread with it, a Pannikin of Ol. Tereb. [rectified oil of turpentine] with others of Digestive, and Spt. Vini [brandy], some Pledgets ready spread with this; a large Rowl of Cerate [a hard medicated paste consisting of lard or oil mixed with wax or resin] well malaxed [kneaded] with Tereb. Venet. [Terebinthina Veneta - Venice Turpentine] to make it sticky"34.

Van Swieten's list is a bit different.

You must also have near you your ung. basil. [black resin - from boiled down turpentine] — e gum. elem. [Gumme Elemini - gum resin] — sambucin [elder flowers]; ol. lin. [linseed oil] — olivar. c.[possibly an olive-based compound] — terebinth [turpintine]; bals. terebinth [distilled turpentine]; tinct. styp. [a styptic tincture] — thaebaie; sp. c. c. [spirit of harts horn] per se. — vol. aromat. — lavend. c. [lavender compound] Wine, punch, or grog, and vinegar in plenty."35

You will notice that three of the last four ingredients in Van Swieten's list are alcoholic. Atkins advises, "To all we must give Cordials [alcoholic beverages] at this Time; and Wine has, in my Opinion, the Preferences; because we are to quench Thirst, as well as refresh the Spirits."36 You might think that that Atkins is suggesting the surgeon get men drunk so that the pain would be dulled or they pass out. (An image that some movies have advanced.) However, a drunken man would not make for a good patient for many obvious reasons; the spirits were probably given in some moderation to passify the patients while they waited for the surgeon's attention.

1 John Covel, "Extracts from the Diaries of Dr. John Covel, 1670-1679," Early Voyages and Travels in the Levant, edited by J. Theodore Bent, p. 129; 2 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 148; 3 Robert Young's Journal cited in Jonathan Charles Goddard, "An insight into the life of Royal Naval surgeons during the Napoleonic War, Part 2," Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service, Spring 1992, p. 28; 4 Baron Gerard Van Swieten, The Diseases Incident To Armies, With The Method Of Cure, 1776 Translation of 1758 Original, p. 129; 5 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 50; 6 Moyle, p. 48; 7 Van Swieten, p. 131; 8 Samuel Leech, Thirty Years From Home, p. 142; 9 Moyle, p. 48; 10 Atkins, p. 148; 11 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, p. 452;12 Van Swieten, p. 132; 13 Moyle, p. 48-9; 14 Van Swieten, p. 132; 15 Ibid;; 16 Zachary Friedenberg, Medicine Under Sail, p. 124 & Stephen Bown, Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentleman Solved the Greatest Medieval Mystery of the Age of Sail, p. 93; 17 Guy Williams, The Age of Agony, p. 117; 18 Van Swieten, p. 120; 19 Lionel Wafer A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America, p. 55; 20 Cited in Sir Cecil Wakely, Surgeons and the Navy, transcript of Thomas Vicary Lecture delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons in England on 11/14/1957, p. 284; 21 Moyle, p. 49; 22 Ibid; 23 Atkins, p. 148; 24 Ibid., p. 149; 25 Van Swieten, p. 132; 26 Ibid., p. 129; 27 Atkins, p. 148; 28 Moyle, p. 49; 29 Van Swieten, p. 129-30; 30 Atkins, p. 149; 31 Van Swieten, p. 130; 32 Ibid., p. 132; 33 Moyle, p. 49; 34 Atkins, p. 149; 35 Van Swieten, p. 132; 35 Atkins, p. 149