The Pirate Surgeon's Quarters: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Next>>

The Pirate Surgeon's Quarters in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 10

Location of the Sick on a Ship

"I went down presently to my quarters, which was a platform in the after part of the hold laid over with beds to put the wounded men on, and under the scuttle [hole in the floor above] they were to come down at lay a heap of cloths for their soft and easy descent, to be dressed." (James Yonge, The Journal of James Yonge [1647-1721] Plymouth Surgeon, p. 41)

At the time of that account, Yonge was serving as a surgeon's assistant on the naval ship Montague, "a third-rate frigatt", in 1661 in Algiers.1 While he was describing a temporary sick bay during battle, it was not usual for naval ships to have semipermanent quarters set up for the recovering sick. This makes sense given that some of the operations during this time involved weeks and even months of recovery time. Karl Vogel explains that a sick bay on a ship "was set aside for hospital purposes, though originally its location was not definite and varied according to the convenience of the moment."2

Photographer: Wolfgang Sauber

A Comfortable Spot? A Replica of the Cannon Deck of the 1627 Vasa

Even as late as the Napoleonic wars, "space would be assigned for the sick by the captain, and this was frequently either under the forecastle or just been a space between two gun ports."3

This is despite the fact that official measures had been taken to assure the sick and wounded had a place to recuperate in 1730, demanding that "[c]onvenient room shall be made between Decks in all His Majesty's Ships, for the Reception of sick or hurt Seamen".4

Yet, as often happens with such lofty government edicts, the rules were not specific and some of the sick and ill sometimes found themselves recovering their health in "the interval between two guns, or any space between decks, which is sometimes formed into a sort of apartment by means of a partition made of canvas."5

Given that the British Navy didn't establish permanent sick quarters for the ill and recovering, one can only

Artist: Howard Pyle

imagine what the pirates did. We know they did something, based on the example of James Skyrme mentioned previously, which noted that "he had really for several Months past been sick, and disqualified for any Duty"6. It seems likely that the ill man would be left in his hammock and ministered to as the captured surgeon could. The separation of ill men from the well seems like a pointless effort on a pirate vessel. As we've learned, pirates often knocked down the walls below decks which would negate any potential benefit received by segregating sick men.

In Skyrme's case, there were several surgeons on board Roberts' fleet. Although the quality of care these men received may be questionable. "[E]ven Roberts told [surgeon George Wilson] (on the Complaint of a wounded Man, whom he had refused to dress) that he was a double Rogue, to be there [among the pirates] a second Time, and threat'ned to cut his Ears off."7

1 James Yonge, The Journal of James Yonge [1647-1721] Plymouth Surgeon, p. 39; 2 Karl Vogel, "Medicine at Sea in the Days of Sail," Milestones in Medicine, p. 92; 3 Jonathan Charles Goddard, "An insight into the life of Royal Naval surgeons during the Napoleonic War, Part I," Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service, Winter 1991, p. 212; 4 Great Britain Privy Council, Regulations and Instructions Relating to His Majesty's Service at Sea, 9th Ed., p. 55; 5 Gilbert Blane, Observations on the Diseases of Seamen, footnote, p. 262; 6 Captain Charles Johnson, The General History of the Most Notorious Pirates, p. 305; 7 Johnson, p. 314

Conditions in the Sick Bay

"Here I saw about fifty miserable distempered wretches, suspended in rows, so huddled one upon another, that not more than fourteen inches space was allotted for each with his bed and bedding; and deprived of the light of the day, as well as of fresh air ; breathing nothing but a noisome atmosphere of the morbid steams exhaling from their own excrements and diseased bodies, devoured with vermin hatched in the filth that surrounded them, and destitute of every convenience necessary for people in that helpless condition." (Tobias Smollett, The Adventures of Roderick Random, p. 170)

Although Smollett's book is a work of fiction, often exaggerated for sarcastic effect, it can be supported in tone. As mentioned on the first page, the Rules for the Cure of Sick or Hurt Seamen on board their own Ships published in 1730 ordered the captain to have men take care of the sick and wounded and keep the sick bay clean1, suggesting that men had not been well attended and the quarters not clean before then.

Nor did the Rules seem to have any long-term effectiveness on improving the lot of the sick and wounded, if they had had any effect at all. In 1797, surgeon Jason Farquhar complained that aboard the naval ship Captain, his patients were 'affected with wounds and ulcers…The sick berth was small and uncomfortable and the ship in general very dirty.'"2 Around the same time, naval Surgeon George McGrath reported that the ship had "very poor accommodation for sick men on board of the Russel, which was both cold, damp, and even sometimes wet as the weather during the time we fitted out there was raining without intermission"3.

Perhaps the most graphic description of a naval sick bay came from a chaplain on the British navy ship Gloucester in 1812. Edward Mangin reported that the sick bay was 'less than six feet high, narrow noisome and wet; the writhings, sighs and moans of acute pain; the pale countenance, which looks like

Photo: US Navy

resignation; but is despair; bandages soaked in blood and matter; the foeter of sores, and the vermin from which it is impossible to preserve the invalid entirely free. Its location near the heads, rather than being convenient for the sick men, made it smell all the more, and 'whenever it blows fresh, the sea, defiles by a thousand horrible intermixtures, comes more or less into the hospital.'"4

Given that these were the conditions shipboard in the British Navy where they had rules and regulations to guide them and men supposed to be assigned to keeping the sick bay clean, one can only imagine the conditions in the place where a sick pirate was left to recuperate!

It should again be noted that, like the cockpit and cable tier, the conditions of the sick bay had much to do with the surgeon's concern for and care of it. Writing in the early 19th century, surgeon William Maly of HMS Albion asked the ship's captain about making the sick bay more accommodating to the patients. The captain "immediately afforded to hang conveniently twenty beds taking in two ports, round house and head door, it was filled up with wooden panels, proper persons were appointed to attend on the sick and to the cleanliness of the sick berth, a set of small cots were allowed me, these were kept in readiness so that as men were taken ill of acute disease, he was washed, clean clothes put on and one of the sick beds were allotted him, his hammock carefully aired and put by."5

1 Great Britain Privy Council, Regulations and Instructions Relating to His Majesty's Service at Sea, 9th Ed., p. 55; 2 Jonathan Charles Goddard, "An insight into the life of Royal Naval surgeons during the Napoleonic War, Part 2," Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service, Spring 1992, p. 28; 3 Jonathan Charles Goddard, "An insight into the life of Royal Naval surgeons during the Napoleonic War, Part I," Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service, Winter 1991, p. 212; 4 Kevin Brown, Poxed and Scurvied: The Story of Sickness and Health at Sea, p. 91; Goddard, An insight..., part 2, p. 28

Location of the Sick During Landfall

"In 1695, when the fleet at Tor Bay had many cases, [the surgeon] advised Lord Berkeley 'to have Tents made ashore for the Men that were most afflicted with that Distemper'. Above a hundred were landed and 'had fresh Provisions allowed them, with Carrots, Turnips and other green Trade'...'" (John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, p. 276)

Artist: Gilles Peeters

Coming Ashore (1637-8)

While the navy preferred to land men ashore and put them in hospitals or in people's houses when hospitals weren't available, a ship traveling in the Caribbean, particularly unfriendly or unfamiliar territory, didn't always have the luxury of being able to leave men ashore. Stops during such a voyage were infrequent - navigation was still somewhat imprecise, meaning an intended stop could be missed. Any landfall tended to slow the progress of the ship and run the risk that the men might abandon the ship.

Still, stopping to land was necessary to collect fresh water, wood (for the ship's spars and masts) and fresh meat if they could get it. It was also the best known remedy for men afflicted with scurvy. The cause of scurvy was not understood and its true cure eluded surgeons during the golden age of piracy, but it was widely recognized that something about bringing the men to land eliminated the illness rapidly. As a result, going ashore was the prescribed remedy when all else failed the crewmen of a scurvy-stricken vessel.

In 1670, Edward Barlow detailed a stop the East Indiaman merchant ship Experiment made at the Island of 'Johanna (today part of Comoros). "[W]e put our sick men on shore, and our casks for water; and

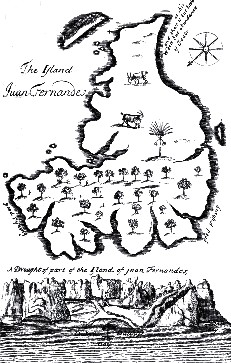

Artist: Edward Cooke

Juan Fernandez Island, Plate 3 from A

Voyage to the South Sea and Round the

World by Cooke (1712)

making a tent there, our cooper fitted them on shore, and the sick men lay in the tent, and having good refreshing [from scurvy], recovered their health apace.

And so fitting all things, and getting water on board, and four or five cows to carry along with us, not intending to stay longer than needs must."1 After 'five or six' days, they left, the men apparently 'refreshed.'

During privateer William Dampier's account of his time with Captain John Cooke, he mentions stopping several times to set up tents for the ill. One such visit was to Juan Fernandez Island in 1684, where they picked up the previously stranded Mosquito Indian 'Will'. Dampier's ship stayed there sixteen days, with "our sick Men were ashore all the time, and one of Captain Eaton's Doctors (for he had four in his Ship) tending and feeding them with Goat and several Herbs, whereof here is plenty growing in the Brooks; and their Diseases were chiefly Scorbutick [Scurvy]."2

When they reached the Galapagos islands, "we made a Tent ashore for Capt. Cook who was sick."3 In 1685, they stopped again in Huatulco

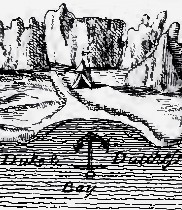

Artist: Edward Cooke

Close Up of Juan Fernandez

Island Profile by Cooke (1712)

(Mexico), where "Captain Swan, who had been very sick, came ashoar, and all the sick Men with him, and the Surgeon to tend them."4

Dampier himself spent time in a tent ashore while being sweated as a treatment for 'Dropsie' (Edema). Sweating was a way to remove bad humors. He was "covered all but my head in the hot Sand: I indured it near half an hour, and then was taken out and laid to sweat in a Tent."5

Accounts of Woodes Rogers' privateering voyage in 1709 likewise mentions making landfall several times including a stop at Juan Fernandez Island, this time picking up the marooned Alexander Selkirk, who would become the inspiration for Robinson Crusoe.

While there, Rogers' crew

Artist: Joseph Nicholls

Lading Supplies on Blackbeard's Ship, from the

General History of the Pirates

(1736)

clear'd up Ship [the Duke], and bent our Sails, and got them ashore to mend, and make Tents for our Sick Men. The Governour [Selkirk] (tho we might have nam'd him the Absolute Monarch of the Islands) for so we call'd Mr. Selkirk, caught us two Goats, which make excellent Broth mix'd with Turnip-Tops and other Greens, for our sick Men, being 21 in all but not above two that we account dangerous; the Dutchess has more Men sick, and in a worse condition than ours.... The Dutchess has also a Tent for their sick Men; so that we have a little Town of our own here, and every body is employ'd."6

In his account of Rogers' crew's time spent on Juan Fernandez Island, Edward Cooke explained that the sick men who were "set ashore, recover'd with eating of Goats Flesh and fresh Fish, only two dying, which were Edward Wilts, and Christopher Williams."7 Rogers provided another explanation of the men's cure, noting that they found a "Herb found by the water-side which prov'd very useful to our Surgeons for Fomentations; 'tis not much unlike Feverfew, of a very grateful smell like Balm, but of a stronger and more cordial Scent: 'tis in great plenty near the Shore. We gather'd many large Bundles of it, dry'd 'em in the shade, and sent 'em on board, besides great quantities that we carry'd in every Morning to strow [cover] the Tents, which tended much to the Speedy Recovery of our sick Men"8.

Artist: Joseph Nicholls

Capt George Lowther and his Company, from

The General History of the Pirates (1734)

In June of 1709, tents were again set up on shore at Port Pences "for the sick who are now much better than when we came to the Island, neither the Weather nor the Air here being half to bad as the Spaniards represented, got the sick Men into their Tents, and put the Doctors ashore with them."9 Not long after, Cooke tells us that "Capt. Thomas Dover, Capt. Robert Fry, and Mr. Stretton, were appointed to command a Bark [at Island Gorgona] and 45 Men in her, and to make what Dispatch they could, returning with such Refreshments as they found for the sick Men."10

The pirates were no strangers to this practice either. In the account of Nathaniel North, we learn that while they were in Mayotta (also part of Comoros today), off the coast of Africa, "a sickness coming among them, they built

Artist: Robert Leslie

Captains Rogers and Dover in a Makeshift Tent Under

Pimento

Trees, from Life Aboard a British Privateer. p. 60

(1889)

huts ashore. They lost, notwithstanding all their care and precaution, their captain and thirty men,

by the distemper which they contracted"11. It is also interesting that they lost so many men, suggesting that this was not scurvy and the shore visit was used for other diseases as well.

Note that author Johnson refers to 'huts' instead of tents, hinting that they built makeshift structures out of what they found on land to shelter their sick. Of course, as mentioned previously, terms were often fluid during the golden age of piracy.

When detailing the construction of his tent on Juan Fernandez Island, Woodes Rogers wrote: "Our House was made by putting up a Sail round four of 'em [Pimento trees], and covering it with another sail. That Capt. Dover and I both thought it a very agreeable Sea, the Weather being neither too hot nor too cold."12 While this could be called a house, it sounds more like an unusual tent.

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 184; 2 Dampier, William, Memoirs of a Buccaneer, Dampier’s New Voyage Round the World, p. 70-1; 3 Dampier, p. 84; 4 Dampier, p. 164; 5 Dampier, p. 322; 6 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World; p. 74; 7 Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World in the Years 1708 to 1711, p. 110; 8 Rogers, p. 76; 9 Rogers, p. 119; 10 Cooke, p. 154; 11 Captain Charles Johnson, The History of the Pirates, p. 191; 6 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World; p. 75