The Pirate Surgeon's Quarters: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Next>>

The Pirate Surgeon's Quarters in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

Pirate Vessels: Small Craft - Pinks

"…the Rose Pink [Capt. Cox, formerly a Man-of-War], was made a Pyrate Ship, which Low himself took the

Artist: Wigerus Vitringa - A Small Pink in a Strong Breeze (1702)

Command of. The Pyrates took several of the Guns out of the French Ship [a ship of 34 guns Low had recently taken to the Azores with him], and mounted them aboard the Rose, which proved very fit for their Turn, and condemned the former to the Flames." (Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 323)

Pinks do not appear to a significant extent in the list of pirates ships, showing up only twice (2% of the total small vessels), as represented by Low's pink Rose and another which which Olivier Levasseur took with his sloop Postillion while traveling in consort with Edward England. Carpenter John Boise attested that Levasseur and England mastered a "French pink, which they fitted out and then sank the Mary Anne [England's sloop] in Samana Bay."1

A pink is a ship type distinct from the other small vessels which appear in this list. Historian Ralph Davis explains that "a pink was simply a pink-steered ship, and a pink stern was one, very narrow at the top and broadening below"2. He goes on to explain that this ship was similar to the Dutch flyboat, noting that "in the late seventeenth century, the term 'pink' was sometimes used almost as a synonym for 'flyboat'"

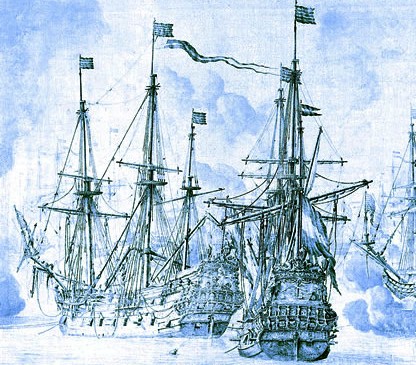

Artist: William van de Velde the Elder

Two Large Dutch Pinks at Bergen in August, 1665, (1669)

3. Ian McLaughlan says that a pink of the mid-seventeenth century was notable for its stern (the back of the ship), which was of a "shape and framing aft [which] was nearly identical to that of its bow and therefore [was] strong. ...most pink-sterned vessels had rather narrow decks aft."4 He also notes that a variant existing around the same time featured "a rather sharper plan as they neared the stern. The conversion of this pointed shape into a square one above the upper wale [a thick plank of wood fastened to the side of a ship to prevent wear] was called a 'cat' stern"5.

Pinks do sort of cross into the sail plan category. A "pink rig" was developed with "the addition of a foremast to the usual ketch sail plan."6 (A ketch rig had a forward mast that was often smaller than its after mast.) "The pink rig is essentially a three mast 'ship' rig, but in the confusing maritime nomenclature of the period, the word 'pink' referred to the stern shape of the vessel as well as the type of rig. Pinks could vary in size. Neither of the pinks in this data indicate the ship burden. Some of the witness accounts for Low's pink Rose report the number of guns the vessel had, although there is wide variance - 147 and 34 guns.8 Still, it must have been a fairly large vessel.

1 CSPC America and West Indies, vol. 30, Item 797. ii; 2,3 Ralph Davis, The Rise of the English Shipping Industry in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, 1962, p. 62; 4,5 Ian Mclaughlan, The Sloop of War: 1650-1763, 2014, p. 54; 6 Mclaughlan, p. 56; 7 Philip Ashton, Ashton's Memorial of Strange Adventures and Signal Deliverance, 1726, p. 25; 8 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 323

Pirate Vessels: Small Craft - Sloops

"Capt Beer… who in that Latitude, about 40 Leagues from Land, was taken by a Pyrate Sloop and 40 Men, commanded by one Paul William Captain, and Richard Cavily Master, both of this Island. This Capt. Williams has a Consort, a very fine London built Galley, of 30 Guns, 200 brisk Men of several Nations; she is call’d the Whido, Samuel Bellame Commander…” (The Boston News-Letter, From Monday April 29 to Monday May 6, 1717)

Photo: Joe Sala - A Model of Samuel Bellamy's Whydah Galley

It is notable that a sloop was instrumental in the taking of the Whidaw, which was to become famous as the vessel Bellamy wrecked on the shoals of Easthampton, off Wellfleet, Massachusetts. This highlights the importance of the smaller vessels such as the sloop in a pirate fleet, particularly in the West Indies and Colonial American coasts. Sloops were usually light and fast, often used in pirate fleets as the reconnaissance and initial contact vessel when chasing a prey ship. In case leading this section, Paulsgrave Williams was able to make the first advance on the superior Galley Ship Whidaw, while Samuel Bellamy came followed in the slower but stronger galley ship Sultana to support Williams in his fight against the Whidaw. This was the best of both worlds for a pirate commodore - he had the speed and agility of the small craft which could catch a target merchant vessel and harry her with shot while the large, slower boat came up with her superior fire- and man-power.

The Whydaw, originally a slave galley, was captained by Lawrence Prince was captured in

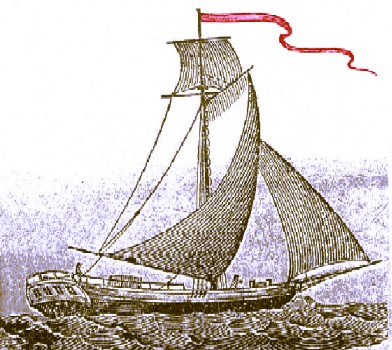

Packet Boat Sloop (1825)

February of 1717. Charles Johnson reports that her "Cargo consisted of Elephants’ Teeth, Gold-Dust, and other rich Merchandize. This Prize not only enrich’d, but strengthened them; they immediately mounted this Galley with 28 Guns, and put aboard 150 Hands of different Nations; Bellamy was declared Captain, and the Vessel had her old Name continued, which was Whidaw"1. This was an excellent ship for Bellamy's pirates but it would probably not have been captured without the initial sortie by Paulsgrave Williams in the 100 ton, 28 gun sloop Mary Anne.2

Sloops make up the vast majority of the small vessels used by pirates during the golden age of piracy according to the data set. Sixty sloops (61%) are found there with four additional hybrid sloops (4%), two having brigantine and two have snow mast/sail combinations. This shows how popular the sloop was among pirates, particularly those who sailed in the West Indies. (The difference between pirates in the East and West Indies is explored in detail on the next page.)

Artist: Peter Monomy

A British Sloop in the Foreground (1720-1730)

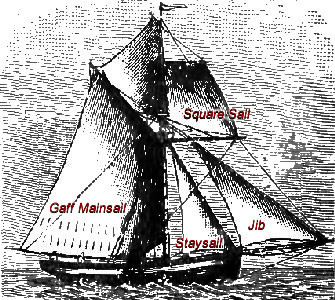

A variety of sail plans were used with sloops. Angus Konstam says that sloops were fitted "with a single mast, rigged with a fore-and-aft rigged mainsail and a jib foresail"3 although he later notes that the term sloop could also refer "to small, two-mast vessels, with a square-rigged mainsail and topsail [and some naval] sloops were three-masted.4 Benerson Little says that this configuration was ideal for the Caribbean because "those mounted with fore-and-aft-sails could more easily beat against the prevailing easterly winds."5

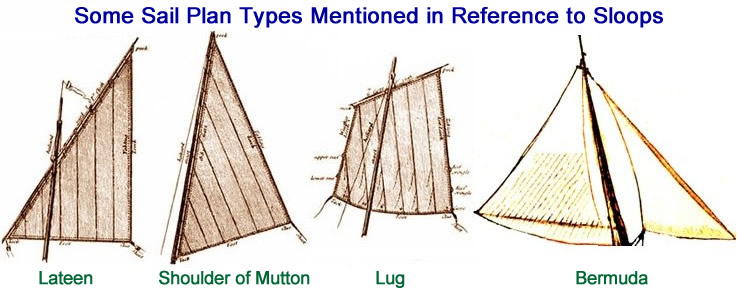

While this sounds fairly neat and tidy, the sail plan for sloops was not quite so straightforward. Commenting in 1750, Portsmouth survey clerk Thomas Riley Blankley explained that sloops "[a]re sailed and masted as Mens Fancies lead them, sometimes with one Mast, with two, and with three, with [sail plans such as] Bermudoes, Shoulder of Mutton, Square, Lugg, and Smack Sails; they are in Figure either square or round Stern'd."6 That vessel description covers a lot of ground. Square sails have been mentioned several times and can be seen in the image at left. Some of the other sail plans for sloops mentioned by Blankley are seen in the graphic below.

Table of Rigging Used on Sloops, The First Three Images are from The Elements and Practice of Rigging and Seamanship by David Steel, 1794 The Last Image is From In the Trade, the Tropics and The Roaring 40s by Anna Brassey, 1885 |

Sloops could also be fighting ships; the navy built sloops of war. David Cordingly uses the Sloop HMS Ferret - the plans of which were drawn in 1711 - as an example of a British sloop-of-war from this time period. "Her gun deck was sixty-five feet and seven inches in length, her keel length (length of the bottom of the vessel) was fifty feet; the breadth inside her [deck] planking was twenty feet and ten inches, and she had a depth of hold [height from the midpoint of the bottom

Edward England and his sloop

the Fancy (early 18th c.)

of the ship to the ceiling of the deck above] of nine feet."7 The Ferret had a burden of 115 tons. She also had 8 ports for oars and was likely a single mast vessel when she was built.8 However, the boat was known to have a second mast five years later.9

Sloops did not have a class rating in the British naval system, although they were recommended to have no more than 18 guns10. Of the 34 sloops in the data for which the number of guns are noted, 33 of them have less than 18 guns. This was likely because the size of these vessels would often have prohibited more. The one pirate sloop having more than 18 guns was one of Jaspar Seagar's consort vessels, which is mentioned as being "a small sloop of 20 guns going to St. Mary’s"11. Although it is just over the limit of the naval recommendation, Benerson Little wryly points out that , "[p]irates particularly relished the prestige of heavily armed ships."12

The number of guns listed for the other 33 sloops ranges from 4 guns (found on John Evan's Scowerer13 (Joseph Cooper's consort sloop14), and James Fife's Elizabeth15) to 12 guns (found in Charles Harris' Ranger16, Stede Bonnet's Revenge17, Edward/Christopher Condent's Duke of York18 and one of Edward Low's (unnamed) sloops.19) So most pirates' sloops were well below the upper gun limit established by the British Navy for sloops of this period.

1 Ed Fox, "21. The Whydah survivors tell their stories, Printed as appendix of The Trials of Eight Persons Indited for Piracy (Boston, 1718), pp. 23-25", Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 86; 2 The Boston News-Letter, From Monday April 29 to Monday May 6, 1717; 3 Angus Konstam, The Pirate Ship 1660 -1730, p. 17; 4 Konstam, p. 18; 5 Benerson Little, The Sea Rover's Practice: Pirate Tactics and Techniques, 1630-1730, p. 54; 6 Thomas Riley Blake, A Naval Expositior, Project Gutenberg eBook #52902, gathered 12/23/18; 7,8,9 David Cordingly, Under the Black Flag, p. 162; 10 Rating system of the Royal Navy, wikipedia, gathered 11/3/12, 1706 Establishment, wikipedia, gathered 11/14/12. and 1719 Establishment, wikipedia, gathered 11/14/12; 11 The Indian Antiquary, S. Charles Hill, ed., Vol. 49 April 1920, p. 62; 12 Little, p. 45; 13 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 337-8; 14 Daily Journal, 8-20-26, Issue 1747; 15 Fox, "60. The Trials of Aaron Gibbens and William Bournal, Proceeds of Court of Admiralty relating to Aaron Gibbens and William Bournal accused of Piracy, 1720 CO 37/10. Ff. 165-171", p. 313; 16 The Weekly Journal or Saturday's Post, Saturday, August 31, 1723; 17 CSPC America and West Indies, Vol. 30, Item 551; 18 CSPC America and West Indies, Vol. 30, Item 551; 19 The Boston News-Letter, Thursday, June 13 to Thursday June 20, 1723

Pirate Vessels: Small Craft - Caribbean-built Sloops

Caribbean-built sloops are specifically mentioned in some of the pirate accounts. Several modern authors wax eloquent about these ships and the pirate's preference for them. David Cordingly explains that "shipbuilders in Jamaica developed a sloop which acquired an

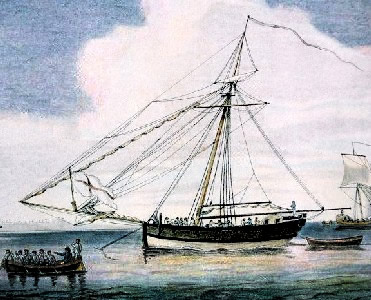

A Bermuda Sloop Fitted out as a Privateer

enviable reputation for seaworthiness and speed."1 Angus Konstam tells us that "many pirates based in the Caribbean favoured the small single-mast sloops built in Jamaica and Bermuda, as both were known to be fast-sailing and sound sea boats."2

Nine vessels are identified as coming from Jamaica, Bermuda and Barbados. Of the 60 sloops found in the data, these nine make up 15% of the total. Among the ships of Caribbean origin were John Rackham's Jamaican Sloop Kingston4, Charles Harris' (Edward Low's consort) Jamaican sloop Ranger5, Benjamin Hornigold's Jamaican sloop Mary Anne6, Captain Harris' unnamed Bermuda sloop7, Thomas Tew's Bermudian sloop Amity8, John Evan's Bermudian sloop Scowerer9, Stede Bonnet's Barbadian Sloop Royal James/Revenge10, an unnamed Barbados sloop captained by Charles Yeats (a consort of Charles Vane) 11 and Robert Sample's Barbados sloop Flying King.12

Thomas Tew's Bermudian sloop was one of two which had been purchased

Caribbean Sloop Sail Plan from Chambers's Twentieth Century

Dictionary

of the English Language (1908)

as a privateer by the island's governor, Isaac Richier.13 Tew must have thought a lot of the vessel and his sponsor's providing it for him, for he "sent to Bermuda for his owner's account, fourteen times the value of their sloop"14. Curiously, the other Bermuda sloop Richer financed, one supposed to accompany Tew on his privateering voyage that was captained by George Dew, was unable to make the journey and so is not included in this data. Johnson explains that "Dew springing his mast"15 caused him to lose Tew on the way. Whether this was the fault of the boat's construction or crew is never explained.

Benerson Little poetically describes a Bermuda Sloop as being "rakish, its single mast cocked arrogantly, swashbuckingly aft like a shark come to prey, the long bowsprit thrust forward like a sword about to pierce an enemy."16 He goes on, noting that such sloops were built with "an enormous gaff mainsail plus a staysail, jib, and often two square sails, the Bermuda sloop epitomized its predatory purpose."17

All this praise by modern historians aside, the use of Caribbean-built sloops was likely due as much to their availability to the pirates sailing in the West Indies as anything. Ian K. Steel says, "The famous cedar sloops built in Bermuda were marketed throughout the English Americas, but enough of them remained under Bermudian ownership to afford a flourishing intercolonial traffic through their home port. Approximately 70 vessels of Bermudian ownership traded with English colonial ports at the end of the seventeenth century, and between 300 and 400 small, two-masted craft were estimated as being used for fishing and local traffic."17Speed and agility would certainly have made them prized vessels, but pirates still traded them up for other vessels.

1 David Cordingly, Under the Black Flag, p. 163; 2 Angus Konstam, The Pirate Ship 1660 -1730, p. 7; 3 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 624; 4 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 313 & Philip Ashton, Ashton's Memorial of Strange Adventures and Signal Deliverance, 1726, p. 26; 5 Fox, “68. John Vickers describes the arrival of the pirates at New Providence, Bahamas, Calendar of State Papers, Colonial series. 1716-1717, item 240.i", p. 364; 6 The Boston News-Letter, Thursday, June 13 to Thursday June 20, 1723; 7 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 422; 8 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 337-8; 9 The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, 1719, p. iii, & The Boston News-Letter, Monday August 4. To Monday August 11. 1718; 10 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 135; 11 David Marley, Pirates of the Americas, Vol. 2, 2010, p. 763; 13 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson) & 668; 13,14,15 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 422; 15,16 Benerson Little, The Sea Rover's Practice: Pirate Tactics and Techniques, 1630-1730, p. 54; 17 Ian K. Steel, The English Atlantic 1675-1740, 1986, p. 54;