Parasites and Their Treatment Pages: 1 2 3 4 5 Next>>

Parasites and Their Treatment During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 4

Skin Dwelling Parasites

A couple of insects that dwell in the skin in one fashion or another are described in some of the golden age of piracy texts. One of them - the guinea worm - gets into the body through drinking water and eventually pushes its way out of the body through the skin. Another - maggots - feed off infected wounds and actually clean putrid, dead skin. The last - screwworms - get into the body through natural openings or wounds and then burrow into the skin. Let's look at each of them in detail.

Skin Dwelling Parasites - Guinea Worms

Merchant captain Alexander Hamilton gives a fairly good description of a guinea worm infection in his account of the East Indies.

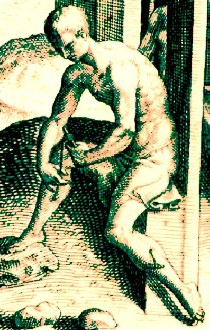

Artist: Johann Theodor de Bry

Removing A Guinea Worm, From Ander

Theil der Orientalischen Indien (1598)

Those who are obliged to drink of the Wells near the town [of Mocha, Yemen] are in Danger of having a long small Worm breed in their Legs or Feet, that inflames the Place where it breeds, which is accompanied with extreme burning Pains. In 5 or 6 Days it appears between the Cutany [cutaneous layer of skin] and outward Skin, and then puts its Head thro’, which when the Patient observes, he takes hold of it with a Pair of Tweezers, and pulls it very gently out, about an Inch or two at a Time, in 24 Hours, and rolls it round an Hen’s Quill, or some other Thing of that Thickness. It is no thicker than the Treble String of a Violin, and I have seen of them, after they have been pulled out, about two Foot and an half long. While it is in the Leg, it is daily covered with a Plaister, and, if it chance to break in the Operation, the Patient will be troubled with intolerable Pains for a long While, and sometimes they are crippled by it.1

This infection is today called dracunculiasis or guinea worm disease. Just as Hamilton explains, people are infected by drinking water which contains water fleas that

Photo: CDC - Extracting A Guinea Worm With a Match Stick

are infected with guinea worm larvae. Nothing happens for about a year, and then the infected patient develops painful burning at the place to which the female worm has made her way and formed a blister in the skin. This is usually in a lower limb. A few weeks after that, the worm makes her way out of the skin.2

Treatment is performed pretty much as Hamilton describes as well. Surgeon William Rayner Thrower explained that "sailors became highly expert at extracting the Guinea worms often picked up in many parts of Africa, India, and South America. This worm, anything from 1 to 3 feet long (30 – 90 cm.), comes to the surface of the skin and can be ‘wound out’ on a piece of stick. It was said to help in bringing out the worm intact first to feed it on milk and butter or apply a poultice of the patients own ordure."3

1 Alexander Hamilton, British sea-captain Alexander Hamilton's A new account of the East Indies, 17th-18th century, p. 49-50; 2 Dracunculiasis, Wikipedia, gathered 1/2/15; 3 William Rayner Thrower, Life at Sea in the Age of Sail, p. 148

Skin Dwelling Parasites - Maggots

Maggots were a particular problem in putrefied wounds of people working in warm, wet climates such as the Caribbean.

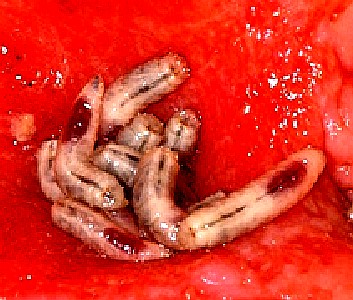

Photo: Wiki User Cedric DW - An Asticot Maggot

It was difficult to fight infection at this time in history given the lack of understanding about what caused it. In the closed, damp and dirty environment of a ship at sea, it was doubly so. During battle, the surgeon operated on the orlop deck, which is located just above the hold - the place where all the filth and water dripping down the inside of the ship collected. So it should not be surprising that maggots, the larvae of flies, would have been plentiful in such an environment.

Sea surgeon John Atkins explained that "A multitude of Maggots [are] frequently seen breeding in warm Countries from large amputated Wounds, discharging a new Æquivocal Generation [of maggots] every Day; [they] have their Life from a Defect of our Compound at the Part"1. He seems to be suggesting that the medicines ['our Compound'] were not equal to the task of keeping the maggots from generating.

While dressing men following the battle of St. Quintin in 1557, Ambroise Paré reported that the soldiers had wounds which "were greatly stincking, and full of wormes [maggots] with Gangreene and putrifaction; so that I was constrained to come to my knife to amputate that which was spoyld, which was not without cutting off armes and legges, as also to Trepan [trepanning - cutting holes in the skull] diverse [men]"2. Note that the cutting, amputation and trepanning were responses to the gangrenous skin and putrefied wounds and not to the maggots. Medicines were applied to deal with the larvae. Paré gave another account in 1564 of a man with " a grievous great impostume [abscess] in his throate... I made incisions in his Aposteme [swollen abscess], where there was found a great quantity of creeping wormes as bigge the point of a spindle, having a blacke head [maggots], and there was great quantity of rotten flesh."3

Paré goes on to talk in some detail about an ulcer

Photo: Muhammad Mahdi Karim - Sarcophaga Nodosa Fly On Dead Skin

infested with maggots. He explains that maggots breed in a wound when there is "too great excrementitious [foul] humidity prepared to putrefie [rot] by unnaturall and immoderate heat. Which happens, either for that the ulcer is neglected, or else for that the excrementitious humor collected in the ulcer, hath not open and free passage forth; as it happens to the ulcers of the ears, nose, fundament, neck of the womb, and lastly, to all sinuous [interconnected] & cuniculous [full of windings] ulcers."4 Paré is here suggesting what is called spontaneous generation of the maggots, placing part of the blame for their proliferation on bad humors, a common culprit for health problems during this time. However, Paré also uses the humoral problem to point to the deteriorating flesh as an agent for their generation. He did not recognize flies as the source of the larvae.

Several medicines are suggested for dealing with maggots in period medical books. For 'wormy ulcers' Paré first suggests removing the worms and the decayed flesh. He then advises fomenting the ulcer with a decoction "which is of force to kill them [the maggots]; for if any labour to take forth all that are quick [alive] he will be

much deceived, for they oft times do so tenaciously adhere to the ulcerated part, that you cannot pluck them away without much force and pain."5 Paré's decoction contains several elements that will sound familiar to those who read the section on curing intestinal worms: wormwood, centaury and aloes. It also includes aegyptiacum and horehound.6

Military surgeon Richard Wiseman similarly suggests that "Wounds that are full of Maggots or Worms ought to be washt with a Decoction absinth [wormwood], card. benedict. [carduus benedictus] rad. gentian. [gentian root] Myrrh, aloes, &c. and deterged as abovesaid with Mundificatives [cleansing medicines]"7. Again we see many of the same ingredients that were suggested in the section on destroying intestinal worms.

An extraordinary account one of the survivors of the shipwreck of the Betsy in 1756 off the coast of Surinam reveals some Carib Indian cures for a maggot-infested wounds. The first medicine once again sounds a familiar tone. "They bathed my wounds, which were full of worms, with a decoction of tobacco and other plants."8

The Caribs later used another medicine which the author later explains. "After they had cleansed my wounds of vermin they kept me with my legs suspended in the air and anointed them morning and evening with an oil extracted from the tail of a small crab, resembling what the English call the soldier crab, because its shell is red. They take a certain quantity of these crabs, bruise the ends of their tails and put them to digest in a large shell upon the fire. It was with this ointment that they healed my wounds, covering them with nothing but plantain leaves."9

1 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 376; 2 Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p. 69; 3 Paré, p. 87-8; 4,5 Ambroise Paré, The Wokes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 347; 6 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 347-8; 7 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, p. 349; 8 Edward E. Leslie, Desperate Journeys, Abandoned Souls, p. 169; 9 Leslie, p. 169-70;

Skin Dwelling Parasites - Maggots in Healing

You can't talk about maggots in medicine today without someone mentioning their use in curing persistent wounds. Live maggots of certain flies are used for wound debridement - that is, to

Photo: National Institute of Health - Maggot Wound Therapy

remove the dead skin by eating it. This is done in controlled, sterile settings with specially disinfected maggots that can remove non-healing skin to encourage the body to generate new, healthy skin.1

Some modern authors suggest that this method was recognized in a limited sense by authors from around this period. One book reports that "Military surgeons frequently observed and described the benefits of maggots infesting the wounds of fallen soldiers."2 They point to the account given by "French military surgeon Ambroise Paré (1510-1590), who reported on the Battle of Saint Quinten (1557)"3.

However, if you review the comments by Paré from this battle, quoted near the beginning of this section, you'll find no comments specifically in favor of maggot-ridden wounds. Paré rather dolefully reports at the end of his comments on that battle that he "did for them, all which I could possible, yet notwithstanding all my diligence, very many of them dyed."4 So this is a modern concept, best used with properly cleansed and prepared maggots and not something found useful in ages past. As sea surgeon John Atkins so bluntly explains it, the maggots "can be no worthier than the parent Corruption they spring from, [and are] in my Sight worse."5

1 Maggot, Wikipedia, gathered 1/4/15; 2,3 Wim Fleischmann, Martin Grassberger & Ronald Sherman, Maggot Therapy: A Handbook of Maggot-Assisted Wound Healing, p. 15; 4Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p. 69; 5 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 376

Skin Dwelling Parasites - Screwworms

There are no clear references to screwworms from the period medical and sailor's literature, although Richard Wiseman does mention that wounds can be full of "maggots or worms"1. While this does not specifically point to screwworms, it does suggest a variety of worm-like creatures living in wounds.

Photo: Ewe Gille - Screwworm Myiasis

The lack of period sources for screwworms may be because screwworm larvae look very similar to maggots. This should not be surprising given that they are laid by blowflies who are of the same family as the houseflies and cheeseflies that lay the larvae most commonly referred to as maggots.2

Screwworms cause a very particular skin irritation because their larvae produce myiasis - meaning they can live in and feed on living tissue.3 This takes various forms and produces different effects on the host depending on which type of fly laid the eggs and where they are located.

"Some flies lay eggs in open wounds, other larvae may invade unbroken skin or enter the body through the nose or ears, and still others may be swallowed if the eggs are deposited on the lips or on food."4 These are all likely places for screwworms to thrive because warm and moist conditions are needed to provide a home and food source to the screwworms.5

The first type of screwworm larvae, Cochliomyia Hominivorax, hatch about 12–21 hours after being laid. Once hatched, they dive head-first into whatever food source is nearest, and burrow deeper, eating into live flesh if it is available. This results in a pocket-like lesion that causes severe pain to the host.

The second type of screwworm larvae, Cochliomyia macellaria, feed only on necrotic [dead] tissue of a wound. After 5 to 7 days of feeding, these larvae move away from the food source to pupate.6

Of the two, the Cochliomyia Hominivorax are clearly the more dangerous. Since there are no specific references to this type of pest, we cannot point to cures that were used. Since they were likely lumped in with "normal" maggots, they were probably treated similarly.

1 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, p. 349; 2 Maggot, & Cochliomyia, wikidpedia.com, gathered 1//4/15; 3 Cochliomyia, wikidpedia.com, gathered 1//4/15; 4 Myiasis, wikidpedia.com, gathered 1//4/15; 5,6 Cochliomyia, wikidpedia.com, gathered 1//4/15

Skin Dwelling Parasites - Scabies

Scabies are tiny mites (Sarcoptes scabiei) that burrow

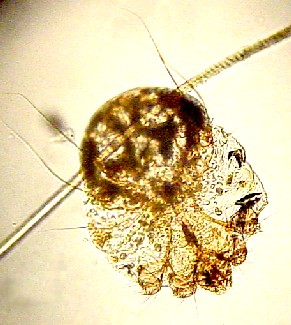

Photo: Kalumet - Scarcoptes Scabiei Photomicrograph

into the skin, causing an alergic response revealed by itching. Scabie comes from the Latin word 'scabere' which means 'to scratch'.1 Guy Williams notes that in England, a scabie infection was often referred to as "the Itch"2, although Emily Cockayne points out that scabies were just one of several causes of itching during this period. She lists it with a variety of other causes including "eczema, impetigo, ‘psorophthalmy’ (eyebrow dandruff), scabies, chilblains, chapped and rough skin, ‘tetters’ (spots and sores), ‘black morphew’ (skin blemishes) and ringworm."3 Still, scabies were a known problem at sea during this time; sea surgeon John Moyle noted that "Divers persons at Sea, and indeed at Land too" were troubled with "scabies, pruritus [itchy skin] and pthiriasis [public lice]."4

The cause of itching created by scabies was still in flux around the golden age of piracy. Sea surgeon John Woodall advised in 1617 that scabies arose from "grosse crudity [of the humors and body], or unnaturall humidity"5. This is what's known as the spontaneous generation theory. However, Italian sea surgeon Consimo Bonomo studied scabies with a microscope in 1687 and was able to give an explanation of the cause of the itch that would make most modern scientists proud. He wrote about his finds in a letter to his mentor Francesco Redi. This letter was published in English physician Richard Mead in 1710.

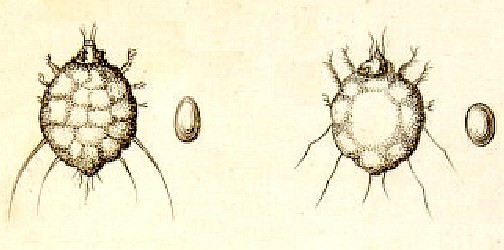

Artist: Costimo Bonomo - Bonomo's Drawings of Scabies and Their Eggs

Bonomo began by watching poor women treating their children who had the itch. He saw them use "the point of a pin pull out of the scabby skin little bladders of water, and crack them like fleas upon their nails"6. This led him to investigate further, working with a pin on the unhealed scabs of people troubled with the problem. "I took out a very small white globule scarcely discernible: observing this with a microscope, I found it to be a very minute living creature, in shape resembling a tortoise of whitish color, a little dark upon the back, with some thin and long hairs, of nimble motion, with six feet, a sharp head, with two little horns at the end of the snout."7 Using his microscope, he drew images of scabies which he included in his letter.

He dismissed the spontaneous generation idea, pointing out the the itch "is no other than the continual biting of these animalcules in the skin, by means of which some portion of the serum oozing out through the small apertures of the cutis, little watery bladders are made, within which the insects continuing to gnaw, the infected are forced to scratch, and by

Photo: Sven Teschke

Scabie Infection of the Hand

scratching increase the mischief, and thus renew the troublesome work, breaking not only the little pustules, but the skin too, and some little blood vessels, and to making scabs, crusty sores, and such like filthy symptoms."8

Bonomo recognized that the itch was spread by mites being transferred from one person to another, "propagated by the means of sheets, towels, handkerchiefs, gloves, etc., used by itchy persons, it being easy enough for some of these creepers to be lodged in such things as those, and indeed I have observed that they will live out the body 2 or 3 days."9 While studying them, he also saw one laying an egg, which ruled out spontanous generation as the creative force behind these mites.

Being Italian, however, Bonomo and Redi had to contend with the church, which was still very involved in science at this time, particularly in Italy. The Pope's chief physician, Giovanni Maria Lancisi thought scabies were humoral in origin.10 While he recognized the presence of the parasite, he discarded it as the only cause of the disease. Bonomo stopped pursuing his research as a result. It is worth considering that there were several different causes of itchy skin, although discarding Bonomo's work set back progress in eliminating the humor-based cures like bleeding and sweating that had grown out of the spontaneous generation theory.

For curing an inveterate itch, our sea surgeons offered some suggestions. We have already seen John Moyle's cure for this once which was the same as his cure for crab lice. To review, he advised purging the patient with calomel and cathartics (medicines to increase defecation) twice a week. He also recommended bleeding the patient, which would be appropriate for the humor-based theory, and bathing the patient in warm salt water, which would help remove the mites. Moyle then covered the affected area with an unguent of calomel, saccharum saturni (acetate of lead) and camphor.11

Fellow sea surgeon John Woodall also suggested bathing the patient, only he used hot salt water combined with strong beer.

Artist: Wiki User Walkerama - Lixivium - Sodium Hydroxide

The patient was to "sit in [the bath] and sweat therein, and after go to a warm bed and sweat againe, and doing so sundry times, they shall feele helpe thereby."12 Sweating is another humoral remedy, designed to purge the body of foul humors.

Bonomo offered a similar suggestion to our other sea surgeons, explaining that while inwardly given medicines failed to work, he had had luck with "lixivial washes, baths and ointments made up with salt, sulphurs, vitriols, mercury's, simple, precipitate [of mercury] or [mercury] sublimate, and such sort of corrosive and penetrating medicines. These being infallibly powerful to kill the vermin lodged in the cavities of the skin, which scratching will never do, partly by reason of their hardness, and partly because they are too minute as scarcely to be found by the nails."13

Bonomo made another extremely astute observation on how to eliminate scabies, explaining that "local treatment had to go on for two or three more days after the cure of the itch. This time would be necessary to prevent relapses because of the presence of eggs that, after hatching, could then start a new biological cycle of the parasite."14

1 Scabies, wikidpedia.com, gathered 1//4/15; 2 Guy Williams, The Age of Agony, p. 195; 3 Emily Cockayne, Hubbub: Filth, Noise, and Stench in England, 1600-1770, p. 95; 4 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 70; 5 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 275; 6,7,8,9,10 Marcia Ramos-e-Silva, "Giovan Cosimo Bonomo (1663 - 1696): Discoverer of the etiology of scabies,", dermato.med.br, gathered 1/15/15; 11 Moyle, p. 70-1; 12 Woodall, p. 275-6; 13,14 Marcia Ramos-e-Silva, "Giovan Cosimo Bonomo (1663 - 1696): Discoverer of the etiology of scabies,", dermato.med.br, gathered 1/15/15