Parasites and Their Treatment Pages: 1 2 3 4 5 <<First

Parasites and Their Treatment During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

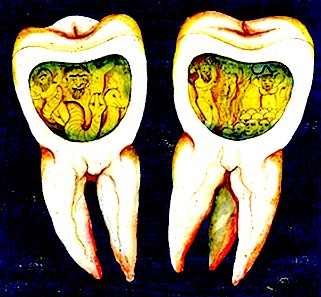

Toothworms

As if ancient physicians didn't have enough to do with the parasites

The Toothworm as Hell's Demon, From an Ottoman

Turk Dental

Book (18th c.)

they knew they had to deal with, they made one up to explain why teeth rotted: toothworms. These little creatures were supposed to reside inside of the tooth, presumably eating away the interior. It is notable that none of the period surgeons or physician under study for these articles mention toothworms. One could validly argue that this is because many of them were ship-based and military surgeons who practiced dentistry only out of necessity. However, this includes the first English book on Dentistry - The Operator For the Teeth, published in 1685 by Charles Allen. He doesn't mention toothworms, even to deny their existence. In a modern paper on he toothworm, Professor Werner Garabek explained, "During the Enlightenment (late 17th - 18th centuries), however, the theory of the tooth-worm was assigned by medical doctors almost exclusively to superstition."2 So it is quite likely Allen did not mention the toothworm because he did not consider the toothworm worth mentioning.

Nevertheless, several physicians did discuss them during the golden age of piracy, although they were all were foreign-practicing, land-based physicians practicing in the 17th century.

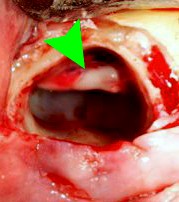

Photo: Coronation Dental Specialty Grp

The Nerve in an Extracted

Tooth

Socket - The Most Likely Source

of the Toothworm Myth

German physician Gabriel Clauder claimed that toothworms caused most of the toothaches in the mid/late 17th century. By way of example, he explained how a tooth which looked healthy on he outside, but caused great pain to the patient, was removed by a tooth-drawer. Once extracted, he split the tooth open where "the little animal whose existence the tooth-drawer had divined, was found to be existing inside"1. Writing in the late 17th century, Danish physician Oligerus Jacobaens likewise advised that while he was "scraping the decaying cavity of a tooth that was the cause of violent pain, he had seen a worm come forth, which, having been put into water, moved about in it for a long time."3

French physician Lazare Riviére, writing in the late 16th and early 17th centuries suggested that the worms were "generated in the carious [decayed] cavities, owing to the putrefaction [rotting] of substances retained in their interior."4 Here again we encounter the spontaneous generation theory of parasites that dates back to the revered ancient authors of medicine.

Writing near the very end of the 17th century, Italian priest and physician Carlo Musitano proposed that the toothworms were not spontaneously generated,

Italian Physician and Priest Carlo Musitano (1709)

but "holds instead that they result from the eggs of flies and other insects, which, together with food, are introduced into the carious cavities and there develop in the heat of the mouth."5 It is a rather interesting that an Italian priest would suggest something counter to the view taken by the Pope's physician in his argument against Giovan Cosimo Bonomo about the origin of the Itch and scabies. It suggests that the scabies controversy was the product of one individual exercising pride over sense.

Several physicians from this era advised methods for drawing the worms out of their teeth. Johann Nikolaus Pechlin, a Dutch Physician and professor of medicine at Kiel in the late 17th century claimed that he had seen five dental worms, "like maggots, come out by the use of honey"6. Musitano suggested that honey was an effective draw for the worms as well.7

German physician Philip Salmuth had another idea, explaining in 1648 that "by using rancid oil he got a worm out of the decayed tooth of a person suffering from violent toothache, thus causing the cessation of pain. The worm, he says, was an inch and a half in length and similar in form to a cheesemaggot."8 Fellow German Gottfried Schulz suggested that by "using the gastric juice of the pig, worms of great size can be enticed out of decayed teeth; some of these even reaching the dimension of an earth worm!"9

Various cures were suggested to get rid of these dental destroyers which were built upon the same idea proposed for eliminating intestinal worms - the use of bitter substances to kill them. Both Lazare Riviére10 and Carlo Musitano11 independently posited this. Musitano suggested several now familiar bitter anti-worm remedies: myrrh, aloes, colocynth and centaurea minor.12

Johann Heurn, a Dutch physician in the early 16th century, recommended another familiar worm eliminator: oil of vitriol. He applied it on broken teeth "by means of a split feather, a drop of oil of vitriol, which, says he, causes the fall of the tooth after a few days."13 He expanded upon this explaining that "to kill them [the toothworms] a drop of oil of vitriol is an excellent remedy; and this at the same time cures the decay of the tooth and takes away the sensibility of the nerve.’"14 Surely the cure was worse than the illness in this case.

1 Vincenzo Guerini, A History of Dentistry, p. 232; 2 Werner Gerabek, "The tooth-worm: historical aspects of a popular medical belief", Abstract, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, gathered 1/18/15; 3 Guerini, p. 231; 4 Guerini, p. 228; 5 Guerini, p. 247; 6 Guerini, p. 232; 7 Guerini, p. 248; 8,9 Guerini, p. 232; 10 Guerini, p. 229; 11,12 Guerini, p. 248; 13 Guerini, p. 213-4; 14 Guerini, p. 214

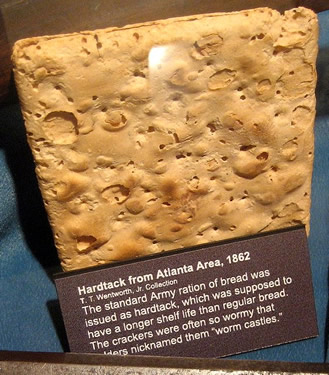

Weevils and Other Beetles

It would hardly be fitting to write an article on golden age of piracy era

Photo: Wiki User Infromation

parasites without mentioning the weevil. Weevils have a long association with sea travel because they ate and bred in dry goods, one of the primary sources of food for the sailor. Writing in November of 1520, Antonio Pigafetta noted, "We were three months and twenty days without getting any kind of fresh food. We ate biscuit, which was no longer biscuit, but powder of biscuits swarming with worms [weevils], for they had eaten the good [parts].”1

Lest you think this was a sign of the times, sea surgeon John Atkins explained over two hundred years later that their ships were troubled with “Worms and Wevils also, that in hot Climates our Bread and Peas are ever subject to"2.

Most of the accounts from the golden age of piracy do not dwell on the subject of weevils in the food, perhaps suggesting that it was just another expected difficulty associated with the job. Several authors in the mid-18th century had no such qualms, however. James Patten, the Surgeon on Captain Cook's section voyage (1772-5), revealed, "our bread was…both musty and mouldy, and at the same time swarming with two different sorts of little brown grubs… Their larvas, or maggots, were found in such quantities in the pease-soup [pea soup], as if they had been stewed over our plates on purpose, so that we could not avoid swallowing some of them in every spoonful we took."3

Period surgeons do not comment on weevils, so there are no suggestions from them about how to get rid of them. This is probably because the weevils were an indirect problem for the sailors health - destroying their sustanance rather than their bodies. Sir Joseph Banks talked about the problem at length in his Endeavor journal in 1769, commenting on what was done in the officer's mess about the problem.

Our bread indeed is but indifferent, occasiond by the quantity of Vermin that are in it, I have often seen hundreds nay thousands shaken out of a single bisket. We in the Cabbin [officer's mess] have however an easy remedy for this by baking it in an oven, not too hot, which makes them all walk off, but this cannot be allowd to the private people who must find the taste of these animals very disagreable, as they every one taste as strong as mustard or rather spirits of hartshorn.4

This brings up an interesting point about eating the weevils found in bread.

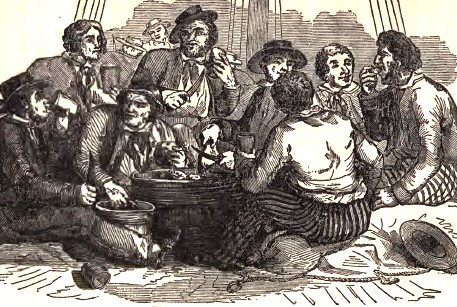

Artist: Robert Billings

Sailors Eating, From The American Cruisers Own Book, by Capt. George Little, p. 45 (1849)

In his book, Stephen Bown says, "Sailors were known to be particularly suspicious of hardtack that contained no weevils or maggots, believing it to be too bad even for these ever-prevalent pests."5 If true, the sailors didn't seem to like them very much. While it is generally safe to consume weevils6, several sources suggest that the taste of the weevils is disagreeable like Banks.

Surgeon Atkins explained that biscuits full of weevils "are not looked on by Sailors the better Being; [they] casting them away contemptuously, as proceeding from a Decay of the Vital Vegetative Principle"7. Even Bown noted that they were bitter to the taste.8 So it is likely that people eating food with weevils in it did their best to remove them.

Understanding just what a "weevil" is in a period text can be tricky because most small brown beetles found in the food stores were called by that name. Yet there are over 60,000 species of weevils, all of which feed on dry foods such as nuts, seeds, cereals and grains.9 Identifying these creatures is even further complicated by the fact that the scientific names of the various species was still in flux.

For example, James Patten identified "two different sorts of little brown grubs, the circulio granorius (or weevil) and the dermestes paniceus" in their bread.10 Despite the apparent scientific naming of these creatures by Patten, neither of these names are used today. Although he specifies that circulio granorius is a weevil, he does not

Photo: Joseph Berger - Ptinus Fur - A Type of Spider Beetle

go differentiate it from the mass of insects called by the name. Given the similarity in the species name, he is most likely referring to what is now called the wheat weevil [Sitophilus granarius].11 In a similar way, Dermestes paniceus was a type of larder beetle identified by Carl Linneaus12 but which is most likely a creature that is called the drugstore beetle (Stegobium paniceum)13 today.

Naturalist Sir Joseph Banks, who made a study of the creatures on Cook's voyage, said: "They are of 5 kinds, 3 Tenebrios [mealworm beetles], 1 Ptinus [a type of spider beetle] and the Phalangium cancroides [phalangium is a type of harvestmen arachnid identified by Linneas14, although this species is not considered a valid attribution today]; this last is however scarce in the common bread but was vastly plentyfull in white Deal bisket as long as we had any left."15

Other books from around the period identify other beetle species, often by various antiquated names such as those used by Patten and Banks. Since this is not a lesson in the history of taxonomy, we will take a brief look at the most likely candidates for bread and pea infestations given in the two above sources: the drugstore beetle, the mealworm beetle and the wheat weevil.

1 Antonio Pigafetta, Primo viaggio intorno al mondo (1519-1522), p. 87; 2 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 376; 3 James Patten, quoted by Stephen R. Bown, Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentleman Solved the Greatest Medieval Mystery of the Age of Sail, p. 19; 4 Sir Joseph Banks, Endeavour journal, 23 September 1769, gathered 1/2/15; 5 Bown, p. 20; 6 FAQ, Extension: Utah State University, gathered 1/2/15; 7 Atkins, p. 376; 8 Bown, p. 20; 9 Weevil, Wikipedia.com, gathered 2/17/15; 10 James Patten, quoted by Stephen R. Bown, Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentleman Solved the Greatest Medieval Mystery of the Age of Sail, p. 19; 11 Wheat weevil, Wikipedia.com, gathered 2/17/15; 12 Dermestes Paniceus, The Linnean Society of London Website, gathered 1/18/15; 13 Drugstore Beetle, Wikipedia.com, gathered 2/17/15; 14 Phalangium cancroides, The Linnean Society of London Website, gathered 1/18/15; 15 Banks, Endeavour journal, 23 September 1769, gathered 1/2/15

Weevils and Other Beetles: The Drugstore Beetle (Stegobium paniceum)

Photo: Wiki User Sarefo - A Drugstore Beetle

The drugstore beetle is also called the bread or biscuit beetle. They are not actually weevils at all, although they are one of the most common non-weevils to infest dried foods. The drugstore beetle is found throughout the world, but tends to be more common in warm than cold climates. The female lays up to 75 eggs at a time with the larval stage lasting up to several months, with the length of time

Photo: Wiki User Kamran

A Drugstore Beetle on a Fingertip

depending on the food source. Larvae cause most of the damage that this species does.

It is notable that this sort of beetle would have been just as troublesome to the surgeon as the cook. The surgeon maintained a variety of dried herbs in his medicine chest that would have been more enticing to this insect than even the food stores.

1 Drugstore Beetle, Wikipedia.com, gathered 2/17/15

Weevils and Other Beetles: The Mealworm Beetle (Tenebrio molitor)

Photo: Wiki User Sarefo - Mealworm Pupa and Molted Larval Skin

Mealworms are the larvae of the mealworm beetle. Mealworms feed on stored grains, vegetation and dead insects. They were probably brought shipboard when in port. Although they are believed to have originated in the Mediterranean region, they are now found around the world, most likely spread by ships.

A female lays about 500 eggs at a time which take 4 – 19 days to hatch. During their larval stage, they feed and molt between each larval stage – which occurs about 9 to 20 times. After the final molting, the larva becomes a pupa, which is whitish. It turns brown over time, and the adult beetle emerges in a few days to a month.1

From their appearance, these would not have been described by period sailors or surgeons as weevils. They would more likely have been called worms or maggots. Both of things are suggested to have been in the period food and medicines2.

1 Mealworm, Wikipedia.com, gathered 2/18/15; 2 See for example Emily Cockayne, Hubbub: Filth, Noise, and Stench in England, 1600-1770, p. 100-1 & 2 John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, p. 8 & 13

Weevils and Other Beetles: The Wheat Weevil (Sitophilus granarius)

Photo: Wiki User Sarefo - A Wheat Weevil

The wheat weevil, also called the grain or granary weevil, occurs all over the world. It damages harvested grains by laying eggs inside grain kernels. Wheat weevils lay 36 to 254 eggs, with one egg usually placed in each kernel. The larvae then feed on the kernel, boring a hole in the grain and emerging. This takes from 5 to 20 weeks, depending on the air temperature; warmer air results in faster growth of a larva.

Wheat weevils lay their eggs in diverse grains including wheat, oats, rye, barley, rice and corn. The weevil itself varies in size, depending on the size of the grain kernels on which they feed. In small grains, such as millet, they are small, but are larger in larger food such as corn.1

1 Wheat weevil, Wikipedia.com, gathered 2/17/15