Parasites and Their Treatment Pages: 1 2 3 4 5 Next>>

Parasites and Their Treatment During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 1

Parasites were an ever-present, commonplace problem to those living during the golden age of piracy. Fleas and lice were no respecters of status. Scabies bit mercilessly. There were no effective sprays or lotions to ward off biting flies, gnats or mosquitos. Worms bred in people's intestinal systems, no doubt finding their way there through the consumption of rotten victuals such as were

Artist: Gustav Doré

Desperately Itching Shipboard, Plate 17, From The Rhyme of

the Ancient Mariner (1866)

frequently found on ships that had been at sea for some time. Weevils nested in the sailor's staple - the ship's biscuit. When explaining conditions aboard a ship on which he was serving, military surgeon Johann Dietz explained that "there was against the mainmast a great tub, fixed some distance from the deck, containing water that was often stinking and full of little worms, for the general drinking."1

Parasites were so ubiquitous, people of the period actually resorted to identifying imaginary insects to explain some health problems - rotting teeth were thought to be infected by tooth worms by some medical authors during this time.

It must be remembered that as miserable as many of these pests sound to us today, they were often a tolerated nuisance at that time. As modern author W.R. Thrower notes, "for centuries lice and fleas were regarded as ‘just one of those things’: their elimination as a domestic pest was not finally achieved until better washing facilities became part and parcel of daily life."2

Some such pests did require medical treatment and sea surgeons discussed procedures necessary for their eradication when the problem was acute and dangerous as we shall see. However, ever-ready to seek new cures, period surgeons sometimes found uses for insects as medicinals! So let's take a closer look at parasites, their impact on the people of the period and treatment by doctors.

1 Johann Dietz, Master Johann Dietz, Surgeon in the Army of the Great Elector and Barber to the Royal Court, p. 409-10; 2 William Rayner Thrower, Life at Sea in the Age of Sail. p. 83

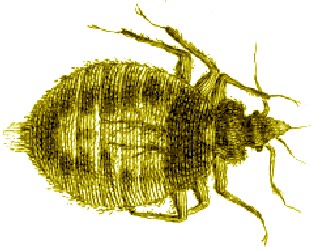

Bedbugs

"…and every evening after we left work we was shut up in this dark stinking hole [in prison in a Portofarino Castle, Tunis], in which we were

Photo: Dr. James Heilman

Bedbug Bites on a Patient's Back

terrified with chinches (some call them [bed] bugs), which bit us and made our flesh come out in bunches..." (Edward Coxere, Adventures by Sea of Edward Coxere, p. 89)

Bedbugs were significantly challenging pests in England during the golden age of piracy. They were usually called 'bugs' or 'buggs' by the English and 'chinches' by residents of many other countries. The company of Tiffan and Son, formed in London in 1690, put out an advertisement explaining that they dealt with extermination of the creatures.1

They weren't just confined to England, however. Stopping in Malaga, Spain during a voyage in 1670, Dr. John Covell noticed that "All that lay on twills and bedsteads were sorely bitten with little [bed] bugs, which left hard knobs and pimples wherever they seised."2

While in West Indies in 1726, John Southall became ill and was advised by 'the best Physicians in Kingstown in Jamaica' to return to England.3 While awaiting passage home, Southall journeyed out "for the Benefit of the Air" where he met a freed slave. The man "perceiving me often [to] rub and scratch, where my Face and Eyes were much swelled with Bugg-Bites, asked me if Chintses (so [Bed] Buggs are by

Photo: Gerard Vandergucht

Bedbug As Figured in John Southall's Book

negroes and some others there called) had bit me?"4 Admitting that they had, the freed man gave him a liquid to treat his bed with that would kill the bedbugs. "Possess'd of this, well pleas'd I went home, and tho' much fatigued, I could not forebear using some of it before I went to sleep... the instant I applied it, vast Numbers did, (as he had told me they would) come out of their Holes and die before my face."5

Killing bedbugs was considered a challenge. Dr. Covell warned that "besides their venomous bite they have (especially if they are bruised) a most intolerable filthy smel. One of our comrades, catching one in the night as it was preying upon him, and thinking it had been a flea (after a slovingly custome which he had got), bit it with his teeth, thinking so to kill it; but the abominable stink set him on vomiting in such a manner as he verily thought he had been poyson'd"6.

So the Jamaican's recipe mentioned by Southall would have been a valuable commodity. With this in mind, Southall returned, trading food and tobacco for the recipe with the free Jamaican. He modified it so it would not ruin the finish on fine furniture and started selling it when he returned to England in 1727, calling it Nonperiel Liquor.7

Photo: Piotr Naskrecki

Bedbug Nymph Feeding on Human Blood

What it contained is unknown, "but it may have been derived from quassia wood, a tropical tree with insecticidal properties"8.

Southall's made many scientific observations of bedbugs which reflected the understanding of the time period. For example, Southall noticed that "Their beloved Foods are Blood, dry'd Paste, Size [glue], Deal [pine wood], Beach, Osier, and some other Woods, the Sap of which they suck"9.

This attraction to natural elements was also noted by Covell, who explained that he and some other of the ship's crew "putt our twills [probably referring to twill mattresses or blankets] for coolnesse into the middle of the floor, which (as all above stairs as well as those below are) was laid with brick, and we escaped all these pestilent companions"10. Most likely the bedbugs preferred the beds to the floor because they could find a regular source of food there.

While bedbugs do no prefer human blood, but will feed on them if they cannot find other prey. They feed through a 'stylet facile' which is a sort of beak with teeth at the tips which move to saw through the skin.

Photo: CDC

Their saliva, which contains anticoagulants and painkillers, is injected into the wound so that the host doesn't feel them biting. Pressure on the blood from the blood vessels they slice into fills them with blood in three to five minutes. Under normal conditions "they try to feed at five- to ten-day intervals, and adults can survive for about five months without food."11

Southall also explained that bedbugs "abound in all foreign Parts, especially in hotter Climates [such as the Caribbean]... 'tis on account all Trading Ships are so over-run with them, that hardly any one thing, if examin'd, will be found free [of them]. And as by Shipping they were doubtless first brought to England, so are they now daily brought. This to me is apparent, because not one Sea-Port in England is free"12. This suggests that the sailors, living in their wooden world of shared quarters, would be forever troubled by them. None of the sea-surgeons from this era suggest cures for them, suggesting that, when present, bedbugs may have been an accepted inconvenience.

1 Michael F. Potter, "The History of Bed Bug Management", American Etymologist, Spring 2011, p. 15; 2 Dr. John Covell, "Extracts from the Diaries of Dr. John Covel, 1670-1679", Early Voyages and Travels in the Levant, p. 5; 3 John Southall, A Treatise of Buggs, p. 115; 4 Southall, p. 6; 5 Southall, p. 8; 6 Covell, p. 116; 7 Southall, p. 14-5; 8 Potter, p. 15; 9 Southall, p. 23; 10 Covell, p. 115; 11 Bed bug, Wikipedia, gathered 1/7/15; 12 Southall, p. 33

Fleas and Lice

Photo: Gilles San Martin - A Head Louse

"I had more than enough to do already, what with tending the ship's crew, patching my clothes and washing my linen; doing, in short, what one must do for himself if he wishes to keep himself free from vermin, which are terribly numerous and are always running up the masts." (Surgeon Johann Dietz, Master Johann Dietz, Surgeon in the Army of the Great Elector and Barber to the Royal Court, p. 129)

Like bedbugs, lice and fleas appear to have been one of those things that people tolerated. Although there appear to have been strata within parasite infection. Thomas Muffet noted in his book on insects that "fleas, while troublesome to all, do not stink like 'wall-lice' [bed bugs] and added that it is no 'disgrace... to be troubled with them as it is to be lowsie' [lousy]."1

Lice

Photo: Kosta Y. Mumcuoglu - Head Louse Bites

troubled everyone. "Samuel Pepys had noticed with sardonic amusement the prevalence of the ‘spotted fever [red spots caused by louse bites] among the aristocracy. The hungry little creatures throve with particularly vigour in dark and badly ventilated dwellings."2

During his time in a prison in a Portofarino Castle, seaman Edward Coxere commented that "lice we had in abundance; so lousy we were that the lice made a prey of us"3. He further explains that he and his fellow inmates "hardly time to kill them. When we had but a little time in the day, off went our clothes and to killing of lice, so that we were seldom idle; for the Turks' opinion was that when we were idle we would be contriving how to make our escape: so by keeping us always employed would prevent the danger."4

Although it was not understood at the time, we know today that lice and fleas are the primary sources of typhus fever. This fever was so associated with dark, dirty, cramped places that it was known during the golden age of piracy by various names such as "jail, hospital, army, or ship fever, and each was thought to arise from the stench of soiled clothing."5 However, since the link between the disease and the insect was not yet made, we will save the discussion of typhus for another article. The important point here is that even before the source was found, typhus was associated with ships, so the problem of fleas and lice was a prevalent one.

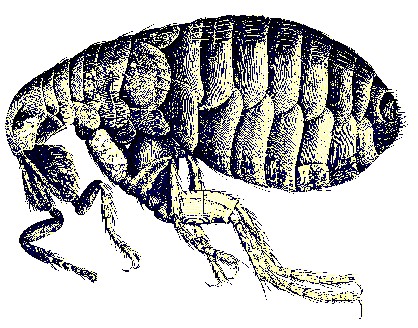

A Flea, Figured in Robert Hooke's Micrographia (1665)

There are many varieties of lice, although only three of them prey on humans. The first two are of the species Pediculus Humanus. "Pediculus Humanus Humanus, or the body louse, sometimes nicknamed "the seam squirrel" for its habit of laying of eggs in the seams of clothing, and Pediculus Humanus Capitis, or the head louse."6 The last type is Pthirus pubis or the crab louse which resides in the pubic hair.

Blood-feeding lice bite their host four to five times a day to feed. "They inject saliva which contains an anti-coagulant and suck blood. The digested blood is excreted as dark red frass."7 Fleas “are wingless, with mouthparts adapted for piercing skin and sucking blood. Fleas are external parasites, living by hematophagy off the blood of mammals and birds."8

No treatment of flea or louse bites is mentioned by any of the period sea surgeon books. On land, physicians working with apothecaries would be responsible for medicines, while surgeons did most of the cutting, bleeding and other mechanical tasks. At sea, the surgeon was often the only medical person on hand, so while he could work medicines, it was not his forte. As a result, sea surgeons likely restricted their comments on medicines to the most urgent health problems. This suggests that flea and louse bites were something more tolerated than treated on ships.

Flea Bites on a Patient's Back and Side

Dealing with fleas and lice was still discussed by some other surgeons, however. While practicing on land, German surgeon Johann Dietz explained, "I was so full of vermin that I got no rest at night. On this account I had to creep stark naked into the hay at night, for only then could I get any rest."9

Avoidance was recognized as a useful louse and flea strategy by sailors as well. While in port in Hanjarr, Hungary in 1676, naval chaplain Henry Teonge noted, "we durst not go to any house in this town for fear of lice, of which cattle the Turks have great store; but we pitched our tent near the town, and had some Turkish food brought to us, which was as bad as it was dear."10

Dietz also goes into some detail explaining how he eliminated such vermin by washing his clothes. "Thus, one puts the dirty linen into a baler or tub and pours fresh water over it (for one can neither drink sea-water nor wash with it); the clothes are then rubbed with soap and are then rinsed in sea-water and hung up on deck and quickly dried."11 Water does little to kill either fleas or lice - a flea takes 24 hours of full submersion to drown and a louse takes about 12 hours. However, soap "can facilitate the death of fleas in bathing.”12

Only one sea surgeon suggests cures for any of these creatures: John Moyle. He explains how to cure Phtiriasis or pubic crabs. First he purges the patient with cathartics (medicine to increase defecation) mixed with calomel - a form of mercury purified by being sublimated several times. He does this twice a week along with bleeding the patient and bathing the patient in warm salt water. He then covers the affected area with an unguent made of calomel, saccharum saturni (acetate of lead) and camphor.

Photo: Radio Tonreg - Persicaria hydropiper

There were some other medicines suggested for dealing with flea and louse bites by land-based apothecaries during this time. Nicholas Culpeper recommended water-pepper (Persicaria hydropiper) be "strewed in a Chamber, [because it] kills all the fleas there"13. He also suggested the use of Pulicaria, a type of Fleabane, explaining that "being burnt, the smoak of it kills all the Gnats and Fleas in the Chamber."14 Physician Robert James likewise advised of Conyza or Fleabane: "The Fume of the Leaves when burned, is said to drive away Gnats, Fleas, and other troublesome insects."15

James had some other suggestions for driving away fleas. He explains that some people "cover the Floors of Rooms with its [the alder tree's] Leaves besprinkled with Dew, in order to destroy Fleas; for the Leaves when budding, contain a Kind of pinguious [fatty] tenacious Humours, to which the Fleas adhering, as it were to Bird-Lime, are killed."16 While interesting and possibly useful on land, this would have been difficult at sea. James also noted that the oil of the arborvitae (an evergreen) "cleanses Beds from Lice and Fleas."17 He similarly explains that kelp (which he identifies as alga angustifolia) will kill lice and fleas.18

Culpeper has several suggestions for dealing with lice. First, he advised Coronaria (probably Gnaphalium), explaining that when "boiled in Ly[e] it keeps the head from Nits and Lice"19. He then mentions Amaranthia, a 'Staechus' (probably a yellow Lavendula or lavender plant), which "being boiled, the water kills Lice and Nits."20 He next recommends stavesaker (Delphinium staphisagria) as an external applications which "kills Lice in the head."21 For a more drastic remedy, we turn to apothecary John Quincy, who noted in the index to his book that "All Mercurial Lotions and Unguents kill lice."22

A Boy Combing Lice Out of His Hair, From Historia Medica, by

Willem

van den Bossche, p. 441 (1639)

Of course, physicians and apothecaries were an expensive prospect for the common men such as sailors. A simpler solution might be the fine-toothed lice combs, which date back to before recorded history.

Hawkers of patent medicines also sprung up to fill the gap. The history of patent medicines is a bit murky and can be hard to find what was available to those seeking such remedies.

However, the widow Read ran an advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1731 for her "well-known Ointment for the ITCH [a scabies mite infection which will be discussed later in this article], with which she has cured abundance of People in and about this City for many Years past.... It also kills or drives away all Sorts of Lice in once or twice using."23 Although the composition of this cure isn't known, Guy Williams noted that "the most successful anti-scabies salves sold by the other quacks of the time depended on their effectiveness of a high sulfur content."24

1 Emily Cockayne, Hubbub: Filth, Noise, and Stench in England, 1600-1770, p. 57; 2 Guy Williams, The Age of Agony, p. 81; 3,4 Edward Coxere, Adventures by Sea of Edward Coxere, p. 89; 5 Zachary B. Friedenberg, Medicine Under Sail, p. 75; 6 Sucking louse, Wikipedia, gathered 1/6/15; 7 Head louse, Wikipedia, gathered 1/6/15; 8 Flea, Wikipedia, gathered 1/6/15; 9 Johann Dietz, Master Johann Dietz, Surgeon in the Army of the Great Elector and Barber to the Royal Court, p. 87; 10 Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, Chaplain on Board H.M.'s Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, 1675-1679, p. 144; 11 Dietz, p. 129; 12 Flea, Wikipedia, gathered 1/6/15; 13 Nicholas Culpeper, Pharmacopœia Londinesis, p. 33; 14 Culpeper, p. 35; 15 Robert James, Pharmacopœia universalis, p. 299; 16 James, p. 220; 17 James, p. 456; 18 James, p. 475; 19 Culpeper, p. 25; 20 Culpeper, p. 38; 21 Culpeper, p. 44; 22 John Quincy, Pharmacopoeia Officinalis & Extemporanea, p. 409; 23 David Dary, Frontier1 Medicine, p. 32; 24 Williams, p. 197-8;