Drowning and Resuscitation Pages: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Next>>

Resuscitation of Drowning Victims at Sea, Page 5

Resuscitation Methods

"And now to return to the point: although by the accidents aforesaid, as also by violent stormes, & the darkness of night, too too many following their assayers have beene woefully washed to the shore of suddain death: yet some have bin taken up for dead that with carefull and skilfull usage have recovered both Life the true love of nature, & Health the happinesse of Life." (Stephen Bradwell, Helps for Suddain Accidents Endangering Life, p.97)

Artist: Claude-Joseph Vernet

Getting to Shore After a Shipwreck (1763)

We have looked at eight methods for resuscitating drowning victims, seven of which are documented to have been used by someone during the golden age of piracy. Many surgeons were wont to try anything and everything in an effort to save a patient, so understanding which of the methods they used to revive a drowning victim was almost impossible. Looking back at the resuscitation methodology of the past, K. Garth Huston noted, "No order of priority was given among various methods ...all were thought to be of equal value."1

Huston suggests a reason for this. "The knowledge of physiology had not progressed far enough to separate correct from incorrect ideas. For example, death from drowning was known to be caused by deprivation of air, but the actual mechanism was widely debated."2

Unfortunately, none of our period works engage in the debate about why someone could be revived from near drowning; that appears to have begun after the golden age of piracy in the middle and latter part of the 18th century. However, it is still interesting to consider. For example, John Wilkinson gave a rather interesting theory about what happened to a person who had nearly drowned. His idea revolved around the body's circulatory system.

Now we are very well assured that the blood does not cease intirely to circulate in one, two, or three hours after the person really appears to be dead; the heart still continuing to be in motion, though the lungs do not perform their usual office: therefore the external parts of the body being cold, the limbs become stiff, the vessels are obstructed by the stagnating humours, and the little remaining motion concentrated to the inmost recess of the heart. This points out what we are to do to recover life. In this case we are, if possible, to give vigour to the heart, by irritating its fibres, and by warming the body, to relax the vessels, and to restore the juices to their proper fluidity, that the heart may again have power to actuate them as it ought to do, by which means the lungs will resume their functions, and life be restored.3

Physician William Harvey, From

The Anatomical Exercises of Dr. William

Harvey, Frontispiece

Wilkinson's theory neatly explains why all of the resuscitation methods might work as well as detailing why no single method would be preferable to another. Circulation of the blood had long been recognized, having been written about by physician William Harvey in his book De Motu Cordis in 1629.

Unfortunately Wilkinson's theory was largely incorrect. While the heart can beat for as long as 15 minutes after respiration ceases, it doesn't continue for three hours. Nor do drowning and loss of respiration affect the fluidity of the blood; in fact, recent studies suggest the blood becomes more fluid after death.4 However, without the use of the scientific method to test such theories, anything that seemed to fit the perceived results could be believed.

For now, let's take a look at each of the eight methods used to resuscitate victims, including: warming the victim, rubbing the victim, giving the victim enemas, stimulating the victim's throat, bleeding the victim, physically agitating the victim in some manner, stimulating the victim's nose and giving mouth-to-mouth.

In order to segregate the period material from that which came later I will add a sub-section containing post-GAoP (Golden Age of Piracy) methods.

I will also add more granular information from the Dutch society statistics; with the level of detail contained in the cases, it breaks many of the eight methods of resuscitation into more precise sub-methods. While the post-GAoP information is quite interesting, the reader should be mindful that it cannot be directly tied to period practices.

1 K. Garth Huston, Resuscitation: An Historical Perspective, p. 1-2; 2 Huston,p. 1; 3 John Wilkinson, Tutamen Nauticum or The Seaman's Prevention from Shipwreck, Diseases and Other Calamities Incident to Mariners, p. 4; 4 See S. Takeichi, C. Wakasugi and I. Shikata, "Fluidity of cadaveric blood after sudden death: Part I. Postmortem fibrinolysis and plasma catecholamine level.", The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology, Sept. 5, 1984, p. 223-7

Resuscitation Methods: Warming the Victim

Artist: B. Cole

Blackbeard in His Warm Clothes, Weapons... and Hat

Stephen Bradwell was the first to suggest warming, although his reasoning was quite simple. "If it be cold weather, let all this [resuscitating the victim] be done in a warme

roome before a good fire."1 Sea surgeon John Moyle does not theorize as to why warming works, but he likewise recommends it, advising that a drowning victim should "have warm Clothes put on, and he [should be] laid in his Cabbin, or Hammock."2 Fellow sea surgeon John Atkins suggests that after the patient is somewhat revived, "he should be shifted dry and put between his Blankets, with a Draught or two of warm Wine, close covered, till he finds Warmth and Life returning"3. Note that neither of the sea surgeons suggest using fire to warm the victim; fires were not often lit on a ship, particularly when the ship was underway or the vessel was in battle.

The idea to warm drowning victims probably came about because their bodies were so cold after having been submerged for a long period of time. The human body in water can lose a great deal of body temperature quite rapidly, even in 80 degree water. (Keep in mind the normal body temperature is 98.7 degrees.)

Heating Drowning Victims, Post-GAoP

Wilkinson had another theory as to why warming was important. He felt that it would "relax the vessels, and... restore the juices to their proper fluidity, that the heart may again have power to actuate them"4. He goes on to explain that by warming the victim's body "the

A Nice Warm Fire (On Land)

circulation of the blood will extend itself to the surface, and extremities of the body, whence the vessels disposed through it opening their tubes, the blood will again be impelled from the reanimated heart with due vigour, because those means tend to excite in the heart that projectile energy, which urges on and maintains its natural circulation."5

In the Dutch society's book, they report a similar theory postulated by Dr. Francois Vicentini which incorporates the ever-popular humoral theory. "The humours by stoppage of circulation, and the coldness of the surrounding water, coagulate; it is necessary to render them fluid by a constant and moderate warmth."6

Wilkinson advised that the victim "ought not to be laid upon the cold earth, as is too usually done, but should if possible, after being first immediately stripped of all its wet cloths, be put in some warm place"7. He continues in vivid detail,

It [the victim] should be put into a very warm bed, or laid before a very hot fire; or it may be warmed upon a hot dunghill, or a hot hay-mow; or it may be covered with bakers ashes; or, if near a mill, upon the kiln where oats and corn are dried for grinding: or, if this cannot be done, the people present may warm it by holding the body to their own, and the life be recovered by an application of animal heat: or it may be warmed, in country places, by the means of horses or cows, two, in a stable or cow-house, being brought together and the body laid between them; or agitated by being laid between two horses brought close together, and thus rode or drove for some time (the head of the body, during the operation, being rather inclined downwards) until very hot with the agitation: or the body, well wrapped in warm flannels, may be put into a bed in the midst of three of three or four people... The body may, where they can be had, be warmed by the reiterated application of hot napkins, or such things as are at hand; hot baths where they offer, or hot water, may be used; or the body may be wrapped up in flannels made hot in boiling water, which has often been done on these occasions with good success."8

A Warm Bed, From Ulrich von Hutten in Bed, From De morbo Gallico (1519)

The Dutch society's advertisement to the citizens of Amsterdam contained many of these same suggestions, adding a few new twists such as "hot embers from a brewery, bakehouse, saltern, soap-boilers, or other fabrics; [and] by the skins of animals, especially of sheep"9.

The data from the case studies reported by the Dutch societies presents a mix of specific ways to warm the nearly drowned. In the 111 cases where warming is used by practitioners victims were placed by a fire or in a room warmed by a fire, such as near a baker's oven in 47% of the cases. Patients are clothed or wrapped in warm clothing such as blankets or aprons (used for children) in 41% of the cases. They were put into a warm bed alone 36% of the time and with other people in 10% of the cases. Placing a hot brick or water bottle at the feet of the nearly drowned is employed in 12% of the cases. Note that multiple methods were often used in the same case so the percentages do not add up to 100.

1 Stephen Bradwell, Helps For Suddain Accidents Endangering Life, p.98-9; 2 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 99; 3 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 269; 4 John Wilkinson, Tutamen Nauticum or The Seaman's Prevention from Shipwreck, Diseases and Other Calamities Incident to Mariners, p. 4; 4 John Wilkinson, Tutamen Nauticum or The Seaman's Prevention from Shipwreck, Diseases and Other Calamities Incident to Mariners, p. 4; 5 Wilkinson, p. 5; 6 Thomas Cogan, Memoirs of the Society Instituted at Amsterdam in Favour of Drowned Persons for the Years 1767, 1768, 1770 and 1771, p. 2; 7 Wilkinson, p. 4; 8 Wilkinson, p. 4-5; 9 Cogan, p. 3

Resuscitation Methods: Rubbing the Victim

The only period author from those in this study to suggest rubbing was John Pechlin. He reported in the case of the revival of the gardener of Tronningholm that his body was "rubbed with warm linnen swaths"1. Pechlin is not long on explanations, so it is not certain what his reasoning for rubbing the victim was. The fact that he specifies warm swaths suggests that this may have been an attempt to increase the warmth of the patient.

Rubbing Drowning Victims, Post-GAoP

Not surprisingly, Wilkinson returned to his circulation theory as a justification for rubbing. He coupled rubbing with warming in his explanation, referring to rubbing as "irritating" the body causing it to better circulate the blood, for "by agitating the body in a hundred different manners,

_Francis_Hayman_mid_18th.jpg)

Artist: (after)_Francis_Hayman

An Interior With a Doctor Operating

On a Patient (Mid 18th century)

not suffering it ever to be long in a state of rest" which "maintains its natural circulation."2 Dr. Francois Vicentini echoes this in his suggestions to the Dutch society, reasoning that because movement "which promote[s] the circulation is suspended, they [the parts of the body] should, therefore, be roused by strongly irritating the nerves which belong to these parts."3

Wilkinson offers several suggestions as to how rubbing should proceed. He advises that the patient "should forthwith be rubbed and chafed with brushes or rough cloths, to make it glow all over the surface"4. He also suggests that rubbing be done using "volatile or other spirits... [on] the temples, pit of the stomach, and the region of the heart and throat are to be washed with them."5 The Dutch society's advertisement adds a few new wrinkles to the prescription, explaining that resuscitators should "make use of strong frictions [rubbing] all over the body, particularly down the spine or back from the neck to the rump, with flannels, or cloths, steeped in brandy; or sprinkled with fine dry salt, or with linen wetted with brandy, or some strong volatile salt, as the spirits of ammoniacal salts"6.

The statistical data from the case studies reported by the Dutch society contains 93 cases where rubbing was used. While most of them do not give details, some of the cases provide some interesting specifics. For example, cloth was used to rub the body in 15% of the cases while using a cloth wetted in brandy was employed 7% of the time. A variety of medicines were employed in rubbing, often added as an irritating agent. The most popular was sal ammoniac (ammonium chloride) which was tried in 19% of the rubbing cases. Close behind was brandy and salt, each of which were used 17% of the time. Other elements employed while rubbing a drowning victim included balsam vitae, 'camphire' tincture, carminative, gin, penetrating spirit [some type of alcohol], pepper, rosemary, spirit of hartshorn, theriac, and wine, although none were used in more than one or two cases.

1 John Wilkinson, Tutamen Nauticum or The Seaman's Prevention from Shipwreck, Diseases and Other Calamities Incident to Mariners, p. 2; 2 Wilkinson, p. 5; 3 Thomas Cogan, Memoirs of the Society Instituted at Amsterdam in Favour of Drowned Persons for the Years 1767, 1768, 1770 and 1771, p. 2; 4 Wilkinson, p. 4; 5 Wilkinson, p. 5; 6 Cogan, p. 3

Resuscitation Methods: Giving the Victim Enemas

Enemas seem a rather unusual choice to revive a drowning victim, but they were nevertheless used. There were basically three kinds of enemas recommended by the literature under study: the usual liquid enema, the air enema and the tobacco enema. Of these three, our period sources refer only to the air and liquid enemas.

John Atkins advises that once the surgeon "finds

Ah, the Classic Methods!

A Physician

Giving a Patient an Enema (1700)

Warmth and Life returning, and then give a Clyster [a liquid enema]."1 He provides no further information about what is to be injected via the clyster syringe, but his purpose is probably to encourage the body to void itself of any retained water.

Henry Teonge gives a far more colorful and interesting account of using an air enema during period. Note that I have inserted a paragraph break for easier reading.)

[June 12, 1675] This day at Deal Beach a boat was overturned with five men in it: three leaped out and swam to shore with much ado; the other two were covered with the boat, whereof one was dead and sank; the other, whose name was Thomas Boules (when the boat was pulled off him, which had lain on his head and neck a long time), was carried away with the violence of the water; yet in sight, and by that means was at last hauled out, and there lay on the stones for dead; for this fellow was dead long before.

A traveler, in very poor clothes (coming to look on, as many more did), presently pulled out his knife and sheath, cuts off the nether end of his sheath, and thrust his sheath into the fundament of the said Thomas Boules, and blew with all his force till he himself was weary; then desired some others to blow also; and in half an hours time brought him to life again.2

Teonge was a chaplain on the ship, so he could give no insight as to why this could work. We may guess that it was felt that irritating the body in such a fashion might cause it to revive, but that is only a guess. Its presence does, however, place this type of treatment for drowning firmly in the golden age of piracy.

Giving Enemas to Drowning Victims, Post-GAoP

John Wilkinson's theory on why enemas worked to revive the nearly drowned was the "the intestines or guts; by which means, being warmed and comforted by the insinuated vapor, they will be excited to motion, and may communicate to the parts in their neighborhood an exertion of vital energy to the recovery of life."3

Tobacco Resuscitation From Hungarian Rescue Museum in Orrling

Wilkinson provided a list of ways to use enemas (also called clysters or glisters during period) to help resuscitate the drowned. For liquid enemas, he suggested "Warm clysters of milk, beer, or water, with a small portion of powdered pepper, ginger, mustard, or such kinds of stimulants"3.

However, he advises that of all the rectal applications in a drowning case, "none is found more successful than to inject the fumes of tobacco, which should be introduced as speedily and in as large quantities as possible into the intestines, by such means as offer themselves most immediately."4

The Dutch society were effusive in their praise for the enema, making it first in their advertisement of ways to revive the drowned. They begin by suggesting the practitioner "blow into the intestines through a tobacco-pipe, or the sheath of a knife, cutting off the lower point."5 This neatly echoes Teonge's comment from almost a century earlier. The advertisement continues, advising the operation be performed quickly and "with force and assiduity"6. They also recommend tobacco smoke "instead of simple air or wind, [because] the warm irritating fumes of tobacco are introduced into the intestines."7 More of interest to us, the advertisement touts tobacco enemas as "the first thing that can be tried, and can be executed without loss of time, either in a boat or on land, in short, wherever the drowned person was immediately placed."8 Of course, the boat they are talking about is most likely a small boat sent out to retrieve the drowned.

The Dutch society's case studies show that some form of enema was used in 87 of the 148 cases included in the statistics. The tobacco enema was by far the most popular, being used in 66 cases. The air enema was employed in 24 cases, while various liquid enemas were tried in 14 situations. This probably has much to do with the society's glowing recommendation for smoke enemas in their advertisement.

A Post-GAoP Tobacco Smoke Enema Mystery: The Sailor and the Nearly Drowned Woman

In their article on smoke enemas, Wikipedia reports a case which they claim is one of the earliest documented sources of tobacco enemas, dating from 1746. "On the advice of a passing sailor, the woman's husband inserted the stem of the sailor's pipe into her rectum, covered the bowl with a piece of perforated paper, and 'blew hard'. The woman was apparently revived."9 They further explain that this is based on the work of Richard Mead who first proposed it in an aside to treating mad dog bites in his book A Mechanical Account of Poisons in 1745.10

This fascinated me because if a sailor suggested such a course of action in 1745, perhaps it was long-standing tradition amongst the sea-going. The average sailor of this period is unlikely to have read Mead's book, so he might have gotten the idea from his fellow sailors, right?

The source given for this case was an article in the Lancet which reported:

Artist: Claude-Joseph Vernet

A Smoker Waiting For His Chance to Resuscitate

From A Calm at a Mediterranean Port (1770)

One of the earliest and most graphic accounts of resuscitation by tobacco enema dates from 1746. A man's wife was pulled from the water apparently dead. Amid much conflicting advice, a passing sailor proffered his pipe and instructed the husband to insert the stem into his wife's rectum, cover the bowl with a piece of perforated paper, and "blow hard". Miraculously, the woman revived. The author of this tale cites Richard Mead (1673–1754) who, a year earlier, had recommended tobacco clysters in cases of "iatrogenic" drowning, caused by immersion.11

Unfortunately, the article's author did not give a source for this statement. Wanting to track down the original source, I attempted to contact the author. Failing in that quest, I started digging and found no such case dating that early. I did find a nearly identical story amongst the Dutch cases.

At Amsterdam, on the 17th of September, 1767, an old Woman was taken out of the Rakin, a deep Canal, in which she had lain sunk a considerable time; and being supposed dead, was to be carried away to an Hospital for burial: but Sybrand Yserman, a Skipper of Gouda, who had read the Society's Advertisement, believing that Tobacco–smoke might recover her, made the trial with a lighted pope he had in his mouth; put it up her anus, and taking the bowl in his mouth, blew up the smoke of it, and of another pipe after it, which by degrees so far recovered her, that she was able soon after to be carried home.12

Wilkinson's book (1764) contains another account with features similar to the Lancet article: Neither the date nor source of this case is given, although it has an interesting additional detail at the end for those wishing to try the method at a safer distance.

In the recovery of a Drowned Woman near Geneva, very lately, they used a lighted pipe, with the bowl covered with many folds of paper pierced with holes; by this means it was so ordered that it might be taken into one's mouth and so blown that the smoke came out from the small end of the pipe, by which (being properly applied) a large quantity of vapour was injected into the intestines; which having been done for about five blasts, a rumbling began to agitate the belly of this Drowned Person; after which the mouth discharged some water, and in a few minutes she began to revive. One may also on these occasions, and to hasten the conveyance of smoke to the intestines, light two pipes filled with tobacco, and having put the small end of one of them up the fundament, apply the mouth or bowl of the other lighted pipe to the bowl of that, and the blow a strong blast through both pipes into the bowels of the Drowned.13

Neither of these cases entirely match the one mentioned in the Lancet. This is not to say that such an account does not exist, only that I did not find it.

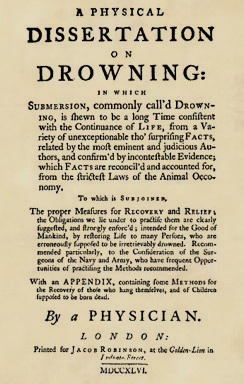

*Update 6/23/16* Ron Trubuhovich found the apparent source used by the article in the Lancet during his research for his doctoral dissertation on resuscitation for the University of

Auckland. He generously shared his discovery with me so I now share it with you. It comes from the 1746 book A Physical Dissertation on Drowning by "A Physician". The account is of a woman who fell out of the stern of a boat which was crossing the river Seine in Passy, France. With the help of their child, her husband went back and found the woman and brought her back to shore. We pick up the account there:

Whilst some of the Spectators of this melancholy Accident were advising to hang her by the Heels; and others ordering different Measures to be taken, a Soldier with his Pipe in his Mouth, came to ask the Reason of such a Concourse of People; upon being inform'd of the Accident, he desir'd the disconsolate Husband to give over weeping, because his Wife would return to Life very soon. Then giving his Pipe to the Husband, he bid him introduce the small End of it into the Anus, put a Piece of Paper perforated with a large Number of Holes upon its Mouth, and thro' that blow. the Smoke of the Tobacco into her Intestines, as strongly as he possibly could. Accordingly at the fifth Blast, a considerable rumbling in the Woman's Abdomen was heard, upon which she discharg'd some Water from her Mouth and in a Moment after return'd to Life.14

This agrees completely with the account found in the Lancet. However, there is an important difference between the Wikipedia article and this one; Wikipedia identifies the man who recommended the procedure as being a sailor, while the actual account specifies that he was a soldier. So, although this does verify the account as taking place sometime during or before 1746, it does not specifically support the idea that sailors made use of the smoke enemas for drowning victims.

1 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 269; 2 Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, Chaplain on Board H.M.’s Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, 1675-1679, p. 75; 3,4 John Wilkinson, Tutamen Nauticum or The Seaman's Prevention from Shipwreck, Diseases and Other Calamities Incident to Mariners, p. 7; 5,6,7,8 Thomas Cogan, Memoirs of the Society Instituted at Amsterdam in Favour of Drowned Persons for the Years 1767, 1768, 1770 and 1771, p. 2; 9 Tobacco smoke enema, wikipedia, gathered 2/21/14; 10 Richard Mead, A Mechanical Account of Poisons. 3rd. ed., p. 175 11 Ghislaine Lawrence, "Tobacco smoke enemas", The Lancet, Vol 359 • April 20, 2002, p. 1442; 12 Alexander Johnson, A Short Account of a Society at Amsterdam Instituted in the Year 1767 For the Recovery of Drowned Persons, p. 11; 13 Wilkinson, p. 7; 14 Author Unknown, A Physical Dissertation on Drowning, 1746, p. 45-6