Fruit in Sailor's Accounts Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Next>>

Fruit in Sailors Accounts During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

Fruit Found In More Than One Sailor's Account, Continued

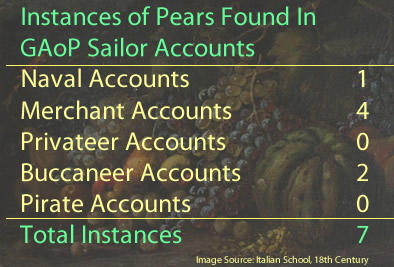

Pear

(Pyrus)

Called by Sailors: Pear

Appear: 7 Times, in 7 Unique Ship Journeys from 6 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Cadiz, Spain; Livorno, Italy; Tenerife, Canary Islands; Basra, Iraq; China; Tabago; Pisco, Peru;

Although pears appear with some frequency in the sailor's accounts, they are never described by them. In fact, there are actually more instances of pears being used to describe other, unfamiliar fruits than there are instances of the pear itself.2 So this fruit was quite familiar to European sailors who appeared to feel it required no description. In fact the only thing related to a descriptions of pears was some found by Edward Barlow in China in 1700 which he said were "indifferent good" and the label 'delicious' being given by East Indies merchant sailor Alexander Hamilton to a list of nine fruits in Basrah, Iraq which includes pears.3 Every other account lists them as one of the fruits they found in the locations listed above.

Fortunately, because pears were so familiar to the Europeans, the physicians and botanists of this period had much to say about them. Botanist John Gerard says that to list all the different types of pears and apples "would require a particular volume... or, to [try to] number those things which are without number."4 (There are currently over

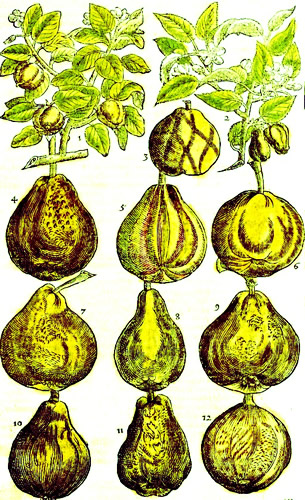

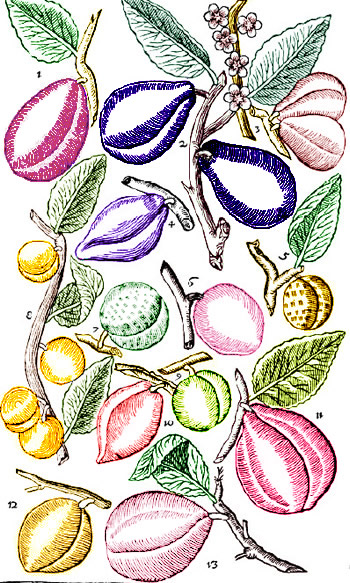

Artist: John Parkinson

Varieties of Pears, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1629)

1- Quince Tree, 2-Portugal Quince, 3-Pear Tree (?), 4-Winter Bon

Chretien, 5-Jerusalem Pear, 6-Bergamot Pear, 7-Summer Bon

Chretien, 8-Warden Pear, 9-Pound Pear, 10- Windsor Pear,

11-Gratiola Pear,

12-Gilloflower Pear

3000 recognized types of pear.5 While this number has certainly expanded during the past three hundred years, it is still shows how much variety must have existed.) French botanist Louis Lémery says, "There are several sorts of Pears as well as Apples, that differ in form, bigness, colour, taste, and smell"6. John Parkinson describes 62 different pears in his book, providing an image of nine of them (and one he doesn't specifically identify) along with 2 types of quinces. (See the image at right. The names listed have been modernized where possible.) Since quinces have their own section, they will not be discussed here.) For the sake of brevity, only the ten pears in his image are discussed in detail here.

Of number 4 in the image, Parkinson says "The Winter bon Chretien is of many sorts, some greater, some lesser and all good". The Jerusalem Pear (5) which he also calls a painted or striped pear, ""is plainly seene to be stript with greene, red, and yellow, as the fruit itself is also, and is of a very good taste". In his text, he divides the bergamot (6) into a summer and winter variety. He says the summer fruit "is an excellent relished peare, flattish, & short, not long like the others with a meane bignesse, of a darke yellowish greene colour". The winter is a "small fruit, somewhat greener than the Summer kindes; all of them very delicate and good in their due time". He doesn't describe the Summer Bon Chretien (7), possibly because it is so similar to the winter fruit. He says the warden pear (8) "or Luke's Wards peare [is] of two sorts, both white and red, both great and small." The pound pear (9) "is a reasonable good peare, both to eate rawe and bake." The Windsor (10) pear "is an excellent good peare, well knowne to most persons, and of reasonable greatness." Gratiola pears (11) are not recognized today. He says they are "a kinde of Bon Chretien, called the Cowcumber peare, or Spinola's peare." Similarly, gilloflower pears do not appear among modern cultivars. Parkinson explains that it is "a winter peare, faire in shew, but hard, and not fit to be eaten rawe"7. These would all have been European pears; it is not clear which type of pears were found by the sailors because they give so little information about them.

Gerard is the only botanist under study to comment on their general flavor. He says the flavor of pears varies, "for some Peares are sweet,divers fat and untious [unctuous - oily], others softe, and most are harsh, especially the wilde peares, and some consist of divers mixtures of tasts, and some having no taste at all, but as it were a waterish taste."8 Although he doesn't say anything about the general flavor of a pear, Parkinson does comment on the taste of individual pears as seen in the previous paragraph.

Parkinson also comments at some length of how pears can be used as food. "They are eaten familiarly of

Artist: Cornelis Jacobsz Delff

Still Life, Pears in a Copper Bowl (1610-20)

all sorts of people, some for delight, and of others for nourishment, being baked, stewed, or scalded."9 He advises that the best pears "serve... to make an after-course for their masters table, where the goodnesse of his Orchard is tried. They are dryed also, and so are an excellent repaste, if they be of kindes, fit for the purpose.10 He also talks at some length about perry, made by fermenting pear juice, which he advises can "be drunke at home, and carried to the Sea, and found to be of good use in long voyages."11 Unfortunately, none of the sailor's accounts from the golden age of piracy mention perry among the drinks available to them at sea. Gerard was writing in the early seventeenth century, so perry use at sea might have been confined to earlier periods.

Humorally, Gerard says all pears are cold.12 Parkinson is a bit more circumspect, citing Galen as his source. "[T]hose that are harsh and sowre doe coole and binde, sweet do nourish and warme, and those betweene these, to have middle vertues, answerable to their temperatures, &c."13 Diverging from the Galenist humoral perspective, Lémery sounds the Paracelsian note, indicating that pears "contain much Oil and essential Salt."14

Medicinally, physician John Pechey says that "Pears are agreeable to the Stomach, and quench Thirst: But they are best baked. Dried Pears stop Fluxes of the Belly."15 The positive impact of pears on the stomach is agreed with by the other botanists and physicians. Lémery says they "create and appetite, and fortifie the Stomach; those that are of a harsh or sour taste are more astringent than other, and fitted to stop a looseness."16 He adds that, moderately eaten, they are appropriate for people of all ages and constitutions. Gerard's comments are similar, although he also says that the more sour pears "may with good successe be. laid upon hot swellings as may be the leaves of the tree; which do both binde and coole."17

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 163 & 518; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 10; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 186; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 78; Jean-Baptiste Labat, The Memoirs of Pere Labat, 1693-1705, John Eadon ed, 1970, p. 262; Bartholomew Sharp, "Captain Sharp's Journal of His Expedition", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 33; 2 See Barlow, p. 86; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 33, 202, 203, 222 & 478; William Dampier. "Part 1", A Supplement of the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 24 & 69; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 136 & 186; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, p. 62; Jean Baptiste Labat, Nouveau Voyage aux Isles de l'Amerique, Tome 1, 1724, p. 343; & Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of Panama, 1903, p. 97; 3 Barlow, p. 518 & Hamilton, p. 78 & 96; 4 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1455; 5 "List of pear cultivars", wikipedia.com, gathered 5/27/22; 6 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 20; 7 John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1904, pp. 592-3; 8 Gerard, p. 1459; 9 Parkinson, p. 594; 10 Parkinson, p. 593-4; 11 Parkinson, p. 594; 12 Gerard, p. 1459; 13 Parkinson, p. 594; 14 Lémery, p. 20; 15 John Pechey, the compleat herbal, 1707, p. 182; 16 Lémery, p. 20; 17 Gerard, p. 1459

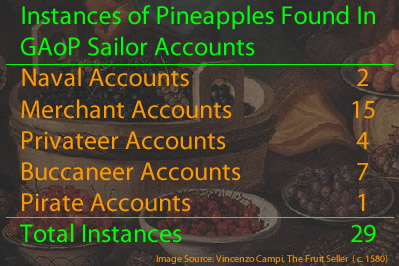

Pineapple

(Ananas comosus)

Called by Sailors: Ananas, Pine Apples, Pine-Apple, Pineapple, Pines

Appear: 29 Times, in 20 Unique Ship Journeys from 12 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Santiago, Cape Verde Islands; Sierra Leone, Africa; Cape Corso Castle, Africa; Principe; Ile de la selle, Comoros Islands; Mocha, Yemen; Bombay, Goa & Karwar, India; Banda Aceh & Java, Indonesia; Bengkulu, Sumatra; Kupang, Timor; Malacca, Malaysia; Borneo; Palau Sabuda, West Papua; Aboyna Cay & Haiphong, Vietnam; Batanes, Philippines; Guam; St. Vincent, Antilles; Barbados; Tabago; Ilha Grande & Salvador, Brazil; Atacames, Ecuador

Pineapples are similar to coconuts in that they appear in a variety of accounts and excited a great deal of commentary by the sailors. They are described in every type of sailor account, although the

Charles II Being Presented with a Pineapple (c. 1675-80)

one mention of them in pirate accounts comes from a description of Principe written by surgeon John Atkins as background material for the General History of the Pyrates. (And, as such, is not a true example of pirates actually eating pineapples, although some almost certainly did.) The majority of these citations are found in merchant accounts with the number of buccaneer accounts running a distant second. (And half of those are actually from William Dampier's exploratory voyage to Australia.)

Curiously, the usually descriptive Dampier, who mentions them 10 different times in his travels, does not describe them in detail. He does mention that the Miskito Indians cultivate "a small spot of Pine-apples; which last fruit is a main thing they delight in, for with these they make a sort of drink which our men call Pine-drink, much esteemed by these Moskito's, and to which they invite each other to be merry"2. He later explains his reticence on the subject: "The Pine-apple and Melon are well known."3 Indeed, pineapples are said by some to have been brought by Columbus to Spain from Guadeloupe in the late 15th century. "They were also famously difficult to transport from the colonies without spoiling, therefore due to their rarity, they became insanely popular and a status symbol in the 16th and 17th centuries."4 In fact, Edward Cooke, captain of the captured ship Marquis on Woodes Rogers' privateer voyage noted that the pineapple "is esteem'd by all Europeans as a most excellent Fruit."5

Fortunately, whatever their knowledge of the fruit, 6 sailors take the

Photo: Wiki User Kaweesaesther - A Growing Pineapple Plant

time to describe pineapples in their accounts. Cooke found them on Guam, where he provided an apt description: "The Fruit is oblong, about a Span in Length, yellow within, with Knobs or Squares on the Outside; whence it has the Name of a Pine-Apple, because resembling those which grow on our Pine-Trees. When ripe, it is yellow and red, with a Tuft of Leaves on the Top."6 Sailor Francis Rogers' description is rather entertaining. "It grows from a plant out of the ground on a high stalk like an artichoke, and is shaped just like those which we call pineapples which grows on the pine trees with us, but they are as large almost as a small sugar loaf."7 Sailor William Funnell estimated that pineapples he found on Aboyna were between two and two-and-a-half pounds8 while buccaneer Lionel Wafer (who is not included in the above count because he was staying on land for an extended period) found those in interior of Panama to be "about six Pound weight; and ...inclos'd with short prickly Leaves like an Artichoke."9

Of the flavor of pineapples, Rogers claims it is "the most delicious of fruit"10. Sea surgeon Atkins says that it is Africa's 'Prince of Fruits'11. Cooke says the "Taste partakes of the Sweet and Sowre, with a most delicious Flavour, extraordinary pleasant."12 Funnell states that "when you bite it, the Juice will run down your Chin and Clothes; and the Liquor is very cool and pleasant."13 Physician Hans

Photo: Adam Jones - Slicing a Pineapple with a Machete

Sloane advised that it had "a very fine flavour and tast... and is accounted the most delicious Fruit these places, or the World affords, having the flavor of Rasberries, Strawberries &c."14 Rogers similarly comments that it contains the "delicious flavour of strawberry, raspberry, peach, or any fruit you shall think of while eating it."15 Atkins is critical of praising the fruit too strongly in this manner, however. "Some of strong Fancy, imagine all sorts of Fruit to be tasted in it; to me, it always left a stinging abstergent [detergent] Flavour."16

Funnell notes that "[w]hen it is ripe, it is yellow and red without, and full of little Bunches"17. Rogers says when preparing a ripe pineapple, "we cut off the outer rough side, and eat all the inside, which is firm, mellow, and juicy". He adds that, "When they are cut green, if they are hung up by the stalk, they will keep several days and ripen as they hang."18 Sloane says once the outer skin is removed, it can be "cut into slices, and so eaten, the middle fibrous or woody part being thrown away."19

A few authors mention seasoning the fruit. Funnell explains that the Dutch "commonly rub it well with Salt, and so let it lye for about an Hour, which takes away the rawness of it; then they wash it in fresh Water, and eat it."20

Artist: Edward Cooke - A Pineapple Plant, From Voyage to the

South Seas,

Volume 2 (1712)

Cooke notes that "[s]ome eat it with Sugar and Water."21 In a related vein, Surgeon Atkins says, they are "eaten with Wine and Sugar."22 Physician Sloane likewise suggests that pineapple slices be "soak'd in Canary [wine] to take off the sharpness which commonly otherways inflames the Throat"23.

This brings us to the medicinal qualities of the pineapple. Several of the sailors commented on this, including one which can be construed to have humoral overtones. Cooke says pineapples are "reckon’d very wholesom, tho' of a very hot Nature, insomuch that they affirm a Knife left sticking in it a whole Day, loses its Temper; yet it has no hot biting Taste"24. Cooke probably got this idea from Portuguese doctor Cristobal Acosta's account of the 'anana'. He says the pineapple is hot and humid and when a knife is left inside a pineapple it 'consumes' the entire knife.25 The only other author to mention the medicinal properties related to the humors of pineapples is Louis Lémery who describes them using Paracelsian-inspired chemical principles: "They contain much Oil, and but little Salt." He later adds that "by their oily substance supply the Blood Vessels with a Chilous Juice [chyle - a milky fluid consisting of fat droplets and lymph], fit for restoring the solid Parts, allaying the sharpness of the Humours, and increasing Milk."26 According to humoral theory, chyle was believed to be an intermediate step between turning food into bodily humors.

Cooke is not alone is providing sailor insight into the medicinal facilities of the pineapple. Sailor Funnell notes that "they are very apt to cause Feavers."27 East India Company Captan Alexander Hamilton likewise states that if most pineapples "are eaten to a small Excess, they are apt to give Surfeits ['Indisposition caused by overeating'], but those of Malacca [in Malaysia] never offend the Stomach."28 Physician Sloane noted that the raw fruit was said to irritate the throat, although he later says he never found that to be the case, except when the juice was distilled. In fact, he promotes the raw fruit as being "a great Cordial to fainting spirits, and helps a squeamish Stomach. Its Juice and Wine is good for the suppression of Urin, and Fits of the Stone [calcinated stones in the urinary tract], as also against Poysons"29. Lémery said that because the pulp was "somewhat solid; [it] is not so easie of digestion, and produces many gross humours.30 Botanist Georg Rumphius has some novel recommendations, writing that "if they are freshly rasped and applied, they will heal all kinds of Ulcers, as well as bad sores on one's footsoles... also other remnants of the Ambonese pox: these same kernels are also much praised against Asthma, if they are well prepared before eating."31

1 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 48 & 217; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 86, 186, 188, 211 & 481; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V1, 1712, p. 9, 26 & 316-7; William Ambrose Cowley, "Cowley's Voyage Round the World", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 25; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 426; Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 23-4, 125, 163 & 181; Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement..., 1700, p. 41; Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 71; Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 56, 72 & 98; Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 79; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 267-8; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 217-8 & 381; Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 185; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 158; Bartholomew Sharp, "Captain Sharp's Journal of His Expedition", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 33; Nathaniel Uring, The Voyages and Travels of Captain Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 106; 2 Dampier,1699, p. 10; 3 Dampier,1699, p. 222; 4 Terry MacEwen. "King Pine, The Pineapple", historic-uk.com, gathered 6/1/2022; 5,6 Cooke, V2, p. 21-2; 7 Rogers, p. 58; 8 Funnell, p. 267; 9 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of Panama, 1903, p. 98; 10 Rogers, p. 58; 11 Atkins, p. 48; 12 Cooke, V2, p. 22; 13 Funnell, p. 267; 14 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 1, 1707, p. 191; 15 Rogers, p. 58; 16 Atkins, p. 48; 17 Funnell, p. 268; 18 Rogers, p. 58; 19 Sloane, p. 191; 20 Funnell, p. 268; 21 Cooke, V2, p. 22; 22 Atkins, p. 48; 23 Sloane, p. 191; 24 Cooke, V2, p. 22; 25 Cristobal Acosta, Tractado de las Drogas y Medicinas de las India, 1578, translated by the author, p. 351; 26 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 51; 27 Funnell, p. 267; 28 Hamilton, p. 381; 29 Sloane, p. 192; 30 Lémery, p. 51; 31 Georgius Everhardus Rumphius, The Ambonese Herbal, Vol. 2, 2011, p. 314

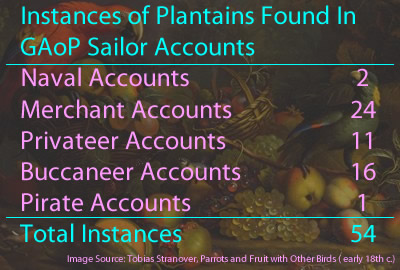

Plantain

(Musa paradisiaca)

Called by Sailors: Plantan, Plantain

Appears: 54 Times, in 26 Unique Ship Journeys from 12 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Isla de Sal & Santiago, Cape Verde Islands; Cape Corso Castle, Ghana; Sherbro, Sierra Leone, Africa; Principe; St. Helena; Cape of Good Hope, Africa; Comoros; Mocha, Yemen; Belopatan, Bombay, Goa, Karwar, Malabar Coast, & Thalassery, India; Sri Lanka; Banda Aceh, Bengkulu (Sumatra), Jakarta, Java, Pulau Bintan, Pulau Buton, Sumatra Straights, Surat & Timor, Indonesia; Palau Sabuda, West Papua; Aboyna Cay & Haiphong, Vietnam; Malacca, Malaysia; Borneo; Batanes & Mindanao, Philippines; Guam; St. Vincent, Antilles; Diarfara, Isla Coiobita & Isla Iguana, Panama; Barbados; Salvador, Brazil; Atacames, Ecuador; Salahonda, Columbia; Gulf of Nicoya, Isla del Cano, Costa Rica;

There is a great deal of support for plantains, although it is concentrated in fewer accounts than some of the other fruits where a large number of instances are found. This has much to do with where the authors traveled. Plantains are found 7 times in William Funnell's account, 13 times in Edward Barlow's accounts and 15 times in William Dampier's various accounts. These three authors account for two thirds of the instances of

Plantain Tree No. 40, Library of Congress

plantains during this period. As with several other fruits from sailors accounts, the single example from a pirate account come from a description provided to the author of the General History of the Pirates by surgeon John Atkins as background material. So there is no account of pirates actually eating plantains, although some of them certainly would have.

About the fruit, William Dampier enthuses, "I take [it] to be the King of all Fruit, not except the Coco it self. ...It is so excellent, that the Spaniards give it preheminence of all other Fruit, as most conducing to Life."2 William Funnell says that "the Fruit grows at the bottom of the Leaf [of a plantain plant], upon a great Stalk, in a Cod of about eight Inches long, and the bigness of a Black-pudding [blood sausage]. The Cod is of a fine yellow colour, often speckled with red."3 Dampier says it looks like 'Hogs-gut Pudding', another type of sausage. The fruit is "about 6 or 7 Inches long, and as big as a Man’s Arm. The Shell, Rind or Cod, is soft, and of a yellow colour when ripe. ...The inclosed Fruit is no harder than Butter in winter, and is much of the colour of the purest yellow Butter."4 Surgeon Atkins notes that they are "shaped like Cucumbers, but slender and longer"5.

Dampier liked the flavor of plantains. He said those growing on Chepelio in Panama in 1685 "are not very large, but the Fruit extraordinary sweet."6 In his multi-page description of the fruit, he noted that a plantain is "of a delicate taste, and melts in one’s Mouth like Marmalet [marmalade]. It is all pure Pulp, without any Seed, Kernal or Stone."7 Funnell calls them "an extraordinary good Fruit"8, although it is not entirely clear that he is referring to the flavor. When privateer George Shelvocke's crew took a town on Coibita Island in their makeshift boat the Happy Delivery, he said they got "some green, ripe and dry'd plantains... which being pounded made a grateful flower to the taste, indifferently white"9. While not exactly the ringing endorsement Dampier gave, the flavor seems to have been sufficient.

Plantains are naturally compared to (or even suggested to be the same as) bananas by some of these authors. Sailor Francis

Photo: Wiki User Rhododendrites - A Plantain and Banana

Rogers uses the words interchangeably in his brief description of the fruit.10 In surgeon Atkins' description of Principe in the General History of the Pirates, he explains "Plantanes and Bananas are Fruit of oblong Figure, that I think differ only secundum Major & Minus; if any, the latter are preferable, and by being less, are juicier"11. He repeats his assertion that bananas are juicier and preferable in his own book.12 In fact, plantains are in the banana plantain family and no sharp distinction between them is noted.13 Both are currently classified as (Family, Genus, Species) Musa X paradisiaca L. Yet there is an important difference between them when it comes to their use as food. The USDA says that "while a member of the banana family, [the plantain] must be cooked to be palatable. It is longer and thicker than regular bananas."14

Despite the USDA's assertion, some of the period authors claimed they could be eaten raw. Rogers (who does lump them together with bananas) says, "When they are ripe, they are yellow, soft and mellow, and as pleasant as a fig."15 This sounds more like the description of a banana than a plantain, however. Funnell specifies that, unlike a banana, which is white inside, a plantain "is yellow like Butter, and as soft as a ripe Pear."16 Although he doesn't say whether the soft fruit should be eaten raw, this suggests it could be. Atkins indicates that they can be "fried or eaten raw"17.

With regard to cooking plantains, Atkins goes to explain that when they are "peeled of their Coat, they are roasted and eat as Bread"18. Dampier's makes a similar comment with more detail.

Photo: Rennet Stowe - Baked Plantain Slices

"When this Fruit is only used for Bread, it is roasted or boil’d when it’s just full grown, but not yet ripe, or turn’d yellow."19 Shelvocke, who captured dried plantains, noted that "all together [the plantains] made up a month's bread, I mean

we ate it instead of bread."20 Edward Cooke mentions that after Rogers' privateers left Guam, "every Man [was] being allow’d four a-Day, instead of Bread, since we left Tacomes [Tacoma, Guam]."21

Plantains were so valuable as a food source that they were purposely cultivated. While recovering from a burned knee with the Kuna natives of Panama, buccaneer Lionel Wafer explained, "None of them [plantains] grow wild, unless when some are brought down the Rivers in the Season of the Rains, and being left aground, sow themselves. The Indians set them in Rows or Walks, without under-wood; and they make very delightful Groves."22

The Europeans also saw some value in their cultivation.

This Fruit is so much esteemed by all Europeans that settle in America that when they make a new Plantation, they commonly begin with a good Plantain-walk, as they call it, or a Field of Plantains; and as their Family increaseth, so they augment the Plantain-walk, keeping one Man purposely to prune the Trees and gather the Fruit as he sees convenient. ...Their common price is half a Riol [Spanish real], or 3d. a Dozen [in the Spanish markets at Havana, Cartagena, Columbia and Portobelo, Panama].23

Photo: Theodor de Bry

Wie sie ire Gasterenen halten (Native Americans prepare a feast), de Bry's America. Pt. 2 (1591)

Barlow mentioned something similar when the East Indiaman Experiment stopped at St. Helena in 1671. "They have planted now some banana and plantain trees"24 for the East India ships which stopped their on there turn trip to England.

Dampier was quite impressed with plantains, spending several pages describing the plant, the fruit and its uses. He provides several recipes. For example, he said the poor and slaves, "make Sauce with Cod-Pepper, Salt and Lime-juice, which makes it eat very savory; much better than a crust of Bread alone. Sometimes for a change they eat a roasted Plantain, and a ripe raw Plantain together, which is instead of Bread and Butter. They eat very pleasant so, and I have made many a good Meal in this Manner."25 He says the English mash several plantains together "and boil them instead of a Bag-pudding; which they call a Buff-Jacket: and this is a very good way for a change."26 Boiled pudding was a standard foodstuff on European ships during this period because cooks could easily prepare it by boiling such bags of flour and fruit in their large cauldrons.

Privateer George Shelvocke's account mentions that plantains could be dried and used in place of flour. Dampier explains this in detail. "[T]he green Plantains slic’d thin, and dried in the Sun, and grated, will make a sort of Flour which is very good to make Puddings. A ripe Plantain slic’d and dried in the Sun may be preserved a great while; and then eat like Figs, very sweet and pleasant. The Darien [Kuna] Indians preserve them a long time, by drying them gently over the Fire; mashing them first, and moulding them into lumps."27 This form of plantain could have been very useful if taken to sea.

Plantains were also fermented. From Dampier:

Waganda Officers (Uganda, Africa) Drinking Plantain Wine,

From the NYPL Digital Collection (1864)The Moskito Indians will take a ripe Plantain and roast it; then take a pint and half of Water in a Calabash, and squeeze the Plantain in pieces with their Hand, mixing it with Water; then they drink it all off together: This they call Mishlaw, and it’s pleasant and sweet, and nourishing: somewhat like Lamb’s-wool (as ‘tis call’d) made with Apples and Ale: and have their whole subsistence. When they make Drink with them, they take 10 or 12 ripe Plantains and mash them well in a Trough: then they ferment and froth like Wort. In 4 Hours it is fit to drink, and then they bottle it, and drink it as they have occasion: but this will not keep above 24 or 30 Hours. Those therefore that use this Drink, brew it in this manner every Morning. When I went first to Jamaica I could relish no other drink they had there. It drinks brisk and cool, and is very pleasant.28

Dampier is not the only sailor to mention drinking the juice of fermented plantains. When Captain Nathaniel Uring was in Honduras in 1711 near the Rio Negro, he stayed with former buccaneer turned logwood cutter Luke Haughten. Uring said at one point that some of Haughten's wives were handing around mishlaw. It was prepared differently than the method Dampier described.

They take of them a certain Number [of plantains] sufficient to make the Quantity of Liquor they design, and squeezing them into small Pieces, put them into a Vessel with as much Water as is proper for fermenting it; and after it has remained in the Vessel two Days, it is fit to drink. The Women that are appointed to serve the Liquor about, dips the Calabash into the Vessel, and takes it out almost full, and with their Hands squeeze the Plantanes and Water together, till it is come to a Pulp, the Liquor running between their Fingers, taking out the Strings, and mixing it well together till it is of such a Thinness fit to drink, and then handed it to the People sitting round29

Physician Hans Sloane gives a slightly different recipe for what he calls 'a pleasant drink': "[W]hen ripe, their Pulp being mash'd with Water till it comes to the Thickness of Honey, it works and clears it self, the thick swimming at the Top, and the thin Drink drawn out of a Tap at the Bottom of the Troughs it's made in."30 He adds that it is consumed all over the West Indies.

Photo: Wiki user Mkumaresa -

A Seeded (Wild) Banana

As with bananas, the period botanists and physicians don't provide information on the humoral properties of the plantain. Comments were made about their impact on health, however. Sloane said plantains were "friendly to the Lungs in their hot Diseases, but

hurtful to the Stomach." He added that they were "very nourishing, windy, venereal [created sexual desire] and adstringent [cleansing], especially if not fully ripe."31 Physician William Hughes commented, "This fruit is excellent good for meat [food] and medicine; good for the Reins, Kidneys, and to provoke Urine... but being immoderately eaten, it oppresseth the stomack". He adds, "they are said to be purging to some if they are freely eaten, yet they are also good against a flux, and that a Dystenteria, as my self have made tryal."32 Atkins mentions that the leaves are "an admirable Detergent, and, externally apply’d, I have seen cure the most obstinate scorbutick Ulcers."33

Dampier mentions the health properties of what he identifies as another type of plantain. "There is another sort of Plantains in that Island [Mindanao, Philippines], which are shorter and less than the others, which I never saw any where but here. These are full of black Seeds mixt quite through the Fruit. They are binding, and are much eaten by those that have Fluxes. The Country People gave them us for that use, and with good success.”34 However, these are not plantains, but seeded bananas, also known as wild or stone bananas - Musa balbisiana or Musa brachycarpa. All other types of bananas, including plantains, are descended from them. They are native to southeast Asia stretching from Indonesia east to the Philippines.35

1 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 48 & 92; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 86, 186, 188, 189, 199, 208, 211, 312, 372-3, 375, 431, & 480-1; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V1, 1712, p. 9 & 316; William Ambrose Cowley, "Cowley's Voyage Round the World", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 2, 16 & 25; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 12, 76, 78, 426 & 455; Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 4, 23, 124, 163, & 181; Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement..., p. 5; Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 33 & 66; Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 72 & 98; Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 79; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 5, 60-2, 132, 151, 267-8, 286 & 293; John Atkins writing in Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 185; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 158 & 178; Bartholomew Sharp, "Captain Sharp's Journal of His Expedition", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 4 & 50; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 296-7 & 300; Nathaniel Uring, The Voyages and Travels of Captain Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 91 & 106; 2 Dampier, 1699, p. 311-3; 3 Funnell, p. 61; 4 Dampier, 1699, p. 313; 5 Atkins, A Voyage..., p. 48; 6 Dampier, 1699, p. 202; 7 Dampier, 1699, p. 313; 8 Funnell, p. 62; 10 Shelvocke, p. 296; 11 Rogers, p. 158; 12 Atkins writing in Defoe (Johnson), p. 187; 13 "Banana", wikipedia.com, gathered 6/2/2022; 14 "Plantain Inspection Instructions", www.ams.usda.gov, gathered 6/2/2022; 15 Rogers, p. 158; 16 Funnell, p. 61; 17,18 Atkins, A Voyage..., p. 48; p. 48; 20 Shelvocke, p. 296-7; 21 Cooke, V1, p. 318; 23 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of Panama, 1903, p. 97-8; 23 Dampier, 1699, p. 313; 24 Barlow, p. 199; 25 Dampier, 1699, p. 313; 26 Dampier, 1699, p. 313-4; 27 Shelvocke, p. 297; 28 Dampier, 1699, p. 314; 29 Uring, p. 152; 30,31 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol2, 1707, p. 142; 32 William Hughes, The American physitian, 1672, p. 75-6; 33 Atkins writing in Defoe (Johnson), p. 187; 34 Dampier, 1699, p. 315-6; 35 "Seeded Bananas", specialtyproduce.com, gathered 6/6/2022;

Plum

(Prunus)

Called by Sailors: Hog plumb, Plumbs

Appears: 4 Times, in 3 Unique Ship Journeys from 3 Sailors Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Tenerife, Canary Islands; China; Rattan, Honduras; Salvador, Brazil

Plums were familiar to European Sailors and rarely rated a description in their accounts. The one exception comes from a very brief mention of two types of plums from Philip Ashton's account of the time he spent stranded on Roatan in Honduras after escaping from Edward Low's pirates in June of 1722. He was stranded for 16 months, initially without any tools. Among the fruits he found during this time were "a sort of small Beech-Plumb, growing upon low Shrubs and a large form of Plumb growing upon Trees, which are called Hog-Plumbs [Spondias mombin - Mombin]"2. Although former Nova Scotia-based fisherman Ashton indicates he wasn't familiar with hog plums, more worldly William Dampier simply includes them in a list of other fruit he doesn't describe when his exploratory voyage to Australia in the Roebuck found them in Salvador, Brazil in March of 1699.3 Fortunately, as with other fruit familiar to the European audience, the botanists and physicians from around the period do describe plums, all noting that they came in a variety of size, shapes, colors and flavors.

Physician William Hughes starts out on a promising note, but rapidly gives up on the venture. "There are in the Island of Jamaica many and different sorts of Plum-Trees; to give a description of which, were too tedious for my intended brevity. The fruit of these Trees, in

Photo: Sam Van Aken - Varieties of Plums, Tree of 40 Fruit

external appearance, resembles some Plums we have here in England, from which similitude they take their names"4. Botanist Louis Lémery agrees, adding a bit of detail.

It's both difficult and tedious to describe here all the different sorts of Plumbs, which are almost innumerable; there are those that are White, Green, Grey, and of several other Colours; they also deduce a difference between them from their bigness, form, taste, and the Places where they grow. Thus some are large, small or middle sized; others round, oval or oblong, some sweet, sharp, or harsh, and accounted more or less so according to the Places from whence they are brought.5

Botanist John Gerard concurs, stating that "every clymat hath his own [plums], farre differing from that of other places: my selfe have sixty sorts in my garden, and all strange and rare: there be in other places many more common,and yet yearly commeth to our hands others not before known"6. Taking on the task squarely, botanist John Parkinson lists 60 different kinds of plum in his book, although several seem to be the same type of plum in different colors. He shows thirteen of them in a diagram in his book, which we will briefly examine. (See his diagram below right, painstakingly colored by the author according to Parkinson's own descriptions.) Where it is is possible to determine what he is talking about, the modern names are mentioned in parentheses.

1. The Imperiall Plum (Imperial Epineuse prune plum) is "a great long, reddish plum, very waterish".

2. The Turkey Plum. (Referring to plums grown in Turkey. Damson?) He describes them as "a very large long blackish plum, and somewhat flat... a well relished dry plum."

Various Plums, From Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, by John

Parkinson (1629)

1. The Imperiall Plum. 2. The Turkey Plum. 3. The red Primordian Plum.

4. The Mussell Plum. 5. The Amber Plum 6. The Queen mother Plum

7. The green Oysterly Plum 8. The Orenge Plum. 9. The Nutmeg Plum

10. The Pescod Plum. 11. The Gaunt Plum. 12. The Date Plum.

13. The early Peare Plum.

3. The red Primordian Plum. "[O]f a reasonable size, long and round, reddish on the outside, of a more dry taste". He also discusses amber and blue primordian plums.

4. The Mussell Plum. He lists them as black, red and white. "The blacke Mussell plumme is a good plumme, reasonable dry, and tasteth well. Red mussel plums are flatter of 'very good taste' and white are smaller and 'not so well tasted.'

5. The Amber Plum. This was "a round plum, as yellow on the outside almost as yellow waxe, of a sowre unpleasant taste". However, he goes on to say that he had had some about the same color that tasted much better so he thought the problem could be due to the first one he tasted.

6. The Queen mother Plum (Myrobalan). He mentions a red and white myrobalan plum with the colors matching the names (although the white has a yellow tinge). The red is "of a better taste than the white."

7. The green Oysterly Plum "is a reasonable great plum, of a whitish green colour when it is ripe, of a moist and sweet taste, reasonable good."

8. The Orenge Plum (probably Mirabelle plums). The Orenge Plum is a yellowish plum, moist, and somewhat sweetish.

9. The Nutmeg Plum. A small plum, "of a greenish yellow colour when it is ripe... and is a good plum."

10. The Pescod Plum. He says these are red, white and green, all 'reasonable' good with the white being relished, "but somewhat waterish" and the green being "big and long pointed".

11. The Gaunt Plum. This is "a great round reddish plum...eaten waterish."

12. The Date Plum. "The white Date Plum is no very good plum. The red Date plumme is a great long red pointed plumme, and late ripe, little better than the white." One cannot help but wonder why he pictured them. Date-plum actually refers to a type of persimmon (Diospyros lotus), although it is not clear if this is what he is talking about. They are yellowish-orange colored.

13. The early Peare Plum. He mentions four pear plums - black, red, white and late white (clearly not 'early'). Of the three colors, he says the white is "early ripe, of a pale yellowish greene colour." However, he says the red and black are like the white, so the name of the plum shown in the image above is unclear. His favorite is the black, which may just have been a riper and sweeter red plum.7

Although Parkinson's descriptions are interesting, their presence in his book does not mean that these were the types of plums mentioned in sailors' accounts. They are only presented here to give an idea of the variations in shape, color and flavor found in European plums according to authors from around this period.

Humorally,

Photo: Homer Edward Price - Hog Plum Tree in Florida

both Gerard and Lémery say that plums are cooling and moistening.8 Lémery indicates that their chemical principles included "a little Oil , much essential Salt and Phlegm; they are good in hot weather for young People that are of a bilious and sanguine constitution."9 This was based on the Paracelsian idea that all things containing three active ingredients, which Lémery called oil, salt and spirit.

Physician John Pechey provides the simplest medical account of plums: "the Sowre bind, the Sweet move the Belly."10 This rather sweeping statement sounds a little too general, however. Lémery divides the properties of plums into good and evil in the marginalia of his book. "[Good effects.] They are of a moistning, cooling, softning and laxative nature; they quench thirst, and create an Appetite. [Evil effects.] Those that have a weak Stomach... ought not eat Plumbs, for they do much weaken it; besides they produce a quantity of gross and Phlegmatick Humors"11. Gerard complains that ripe plums provide "the body very little nourishment, and the same nothing good at all: for as Plumrnes do very quickly rot, so is also the juice of them apt to putrifie in the body, and likewise to cause the meat [food] to putrifie which is taken with them"12.

Botanist Parkinson mentions that Damson plums were dried in France and shipped in casks to England "under the name of Damaske Prunes: the blacke Bulleis [bullace] also are those being dryed in the same manner) that they call French Prunes, [prunes] by their tartnesse are thought to binde, as the other, being sweet, to loosen the body."13 Gerard has a much better opinion of prunes than plums, noting that "are wholsomer, and more pleasant to the stomack, they yeeld more nourishment and better, and such as cannot easily putrifie." He says that Damson prunes are astringent and "stay the belly", although he notes that Galen suggests "they do manifestly loose the belly"14. Today prunes are generally said to increase stool frequency (ie. 'loosen the belly') thanks to the fiber they contain, although some sources suggest they can also cause constipation if enough fluids aren't ingested while increasing fiber intake.15 This may explain the contradictory period descriptions of their impact on digestion and excretion.

1 Philip Ashton, Ashton's Memorial, 1726, p. 47; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 518; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 10 & 66; 2 Ashton, p. 47; 3 Dampier, p. 66; 4 William Hughes, The American physitian, 1672, p. 88-9; 4 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 17; 5 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1497; 6 Gerard, p. 1498; 7 John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1904, p. 575-8;8 Gerard, p. 1498 & Lémery, p. 17; 9 Lémery, p. 18; 10 John Pechey, the compleat herbal, 1707, p. 189; 11 Lémery, p. 17; 12 Gerard, p. 1498; 13 Parkinson, p. 578; 14 Gerard, p. 1498; 14 Summer Fanous, "The Top Health Benefits of Prunes and Prune Juice", healthline.com, gathered 6/8/22;

Pomegranate

(Punica granatum)

Called by Sailors: Pomgranates, Pomegranate, Pumbarnates, Pumgarnates

Appears: 16 Times, in 11 Unique Ship Journeys from 8 Sailors Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Livorno, Italy; Algiers, Algeria; Tunis, Tunisia; Tenerife, Canary Islands; Cape Corso Castle, Africa; Santiago, Cape Verde Islands; Cape of Good Hope, Africa; Basrah, Iraq; Aden, Yemen; Banda Aceh, Jakarta & Timor, Indonesia; Salvador, Brazil; Madeira, Portugal; Chepillo Island, Costa Rica

Pomegranates were apparently well-known enough to period sailors that they didn't see a need to describe them. This is likely because they had been made available to England from Spain, Italy and North Africa. They are used by a couple of sailors to describe other fruits, a sure sign that they were quite familiar to English readers.2 East India sailor Alexander Hamilton does mention that they are one among other 'delicious Fruits' he found in Basrah, Iraq.3 Clergyman

Artist: John Gerard

Pomegranate Tree Types, From The Herball or General Historie of Plantes (1636)

John Covel notes that they 'stockt' their ship with pomegranates which the locals had brought to the merchant vessel London Merchant when they stopped at Tunis Castle in Tunisia.4 However this is all the sailor's accounts under study offer by way of description, so we must rely on the physicians and botanists for details of the fruit itself.

Botanist John Gerard basically divides pomegranates into two types: wild and cultivated (which he calls the 'garden' or 'manured' variety.) He also notes that there is a type of pomegranate tree which doesn't bear fruit, but he doesn't mention it again.5

Of the fruit, Gerard explains that it is "covered with an hard bark of an overworne purplish colour, full of grains and kernells, which. after they be ripe are of a crimson colour: and full of juice which differeth in tast according to the soile, clymat, and country where they grow"6. Parkinson says, "The fruit is great and round, having as it were a crowne on the head of it, with a thicke tough hard skinne or rinde, of a brownish red colour on the outside, and yellow within, stuffed or packt full of small

graines, every one encompast with a thin skin, wherein is contained a clear red juyce"7.

Gerard divides the cultivated fruit into three types by their flavor: "one having a soure juice or liquor, another a very sweet and pleasant liquor, and the third the tast of wine."8 John Parkinson gives a similar description of cultivated pomegranate flavors, using the terms "sower, sweet, and into sower sweete"9. Physician John Pechey calls the flavors "Sweet, Acid and Vinous." He further notes that the "Vinous are of a middle Nature, between Acid and Sweet". 10

Gerard

Photo: Augustus Binu -

Pomegranate Fruit and Juice

says the humoral nature of pomegranates is cool and dry, with the acid-flavored being colder than the sweet and vineous.11 "The use of all these Pomegranets is very much in Physicke [medicine], to coole and binde all fluxibility both of body and humours", according to Parkinson.12

Medicinally, Pechey suggests the sweet pomegranate "is used for Chronical Coughs and a Pleurisie [tuberculosis]; but that it is not good in Fevers because it occasions Wind [gas], and increases the Heat." The acidic pomegranates "are cold, and Astringent, and Stomachick [good for the stomach]... are used to quench Thirst, for Fevers, the Running of the Reins [kidneys], for Ulcers of the mouth and the like." The 'vinous' "are Cordial [warming] and Cephalick [good for the head], and chiefly used for Fainting, and Giddiness, and the like."13 Gerard says the sour pomegranates are binding and work well "for the heart-burn, they represse and stay overmuch vomiting of choler [the humor yellow bile]... they help the bloudy flix [flux], aptnesse to vomit and vomiting." He also says pomegranate seeds help the stomach, "fasten teeth and strengthen the gums"14.

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 58 & 163; John Covel, "Diary," Early Voyages in the Levant, Thomas Dallam, ed., 1893, p. 120; William Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 124-5; Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 10, 33 & 66-7; Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 56 & 72; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 286 & 293; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 78; Raveneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 330; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 174 & 233; Nathaniel Uring, The Voyages and Travels of Captain Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 106; 2 For examples, see Dampier, "Part 1," 1700, p. 125, Dampier, "Part I", 1703, p. 33 & Funnell, p. 286; 3 Hamilton, p. 78; 4 Covel, p. 120; 5,6 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1449; 7 John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1904, p. 430; 6 Gerard, p. 1449; 9 Parkinson, p. 428; 10 John Pechey, the compleat herbal, 1707, p. 322; 11 Parkinson, p. 428; 12 Gerard, p. 1451; 13 Pechey, p. 322; 14 Gerard, p. 1451

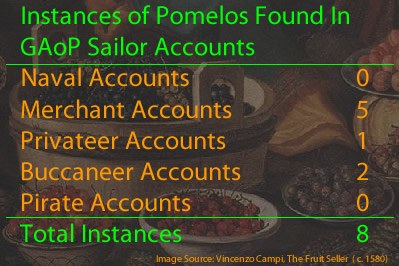

Pomelo

(Citrus maxima)

Called by Sailors: Chaddocks, Limes, Pumblemouses, Pumplemusses, Pumplmouses, Pumplenoses

Appears: 8 Times, in 5 Unique Ship Journeys from 3 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Malacca , Malaysia; Banda Aceh, Java & Sumatra Straights, Indonesia; Kupang, Timor; Guam; Haiphong, Vietnam; Salvador, Brazil

The period sailor's accounts use several terms to refer to pomelos, even identifying them at times as being other fruit. Period sailors most often called them by some phonetic spelling of the Dutch term 'pomplelmoes'. (which literally means 'pumpkin melon'.2) During Edward Barlow's 1672 journey aboard the East Indiaman Experiment in Indonesia, he referred to them as pumplmouses and pumblemouses. They appear several times in William Dampier's accounts, who called them pumple musses or pumplenoses. The seem to have been unfamiliar to both authors. (As well as others. Neither the word 'pompelmous' or variations of it appear in any of English dictionaries published during this period.3)

There is yet another, even more unusual term used for pomelos during this time. When Woodes Rogers privateers visited Guam in March of 1710, captain Edward Cooke of the captured ship Marquis includes "Chaddocks" in his list of fruits found on the island.4

Artist: Samuel Copen - Ships at Bridge Town in Barbados (1695)

This term has an interesting background. It was used primarily to refer to pomelos found in the West Indies. As physician Hans Sloane explains, "The Seed of [the pomelo] was first brought to Barbados by one Captain Shaddock, Commander of an East-India Ship, who touch'd at that Island in his Passage to England, and left its Seed there."5 He notes that he ate 'shaddocks' (among other fruits) for dessert while in Barbados.6 Writing in 1733, University of Cambridge botany professor Richard Bradley helps clarify this. "The Chadock-Orange of the West-Indies is the same as the Pumplemus of the East-Indies"7. Modern authors have tentatively identified Captain Chadock/Shaddock as Philip Chaddock, who is mentioned in letters as being at Barbados in the role of ship's captain between 1642 and 1650.8 He is the most likely source of this story. Yet only one period sailor mentions finding pomelos in the Americas during this period. When Dampier visited Salvador, Brazil, he gives an abbreviated version of the story, noting that they were "first brought from the East-Indies, and they thrive here very well"9.

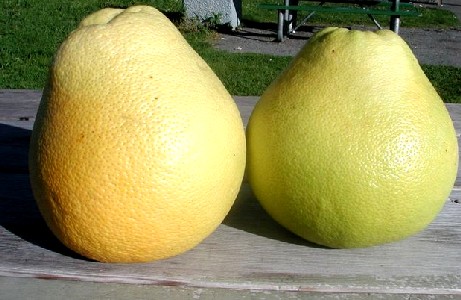

There are a several types of pomelos, some having different appearances. Charles Lockyer of the English East India Company described those he found in Canton, China around 1704 or 1705: "The Pumplemus [pomelo]

Two Pomelos

is like a pale Orange, [it] contains a Substance much like it, and is five times as big. Some have white, and others red Cloves within, but the Colour makes no Alteration in the Tast: There are sweet, bitter, and sour of both sorts, which the Fruiterers themselves cannot distinguish by the Rinds."10

When Dampier was sailing on the East Indiaman Curtane near Achin (Banda Aceh) in 1689, he found pomelos, providing a description of them. "The Pumple nose is a large Fruit like a Citron, with a very thick tender uneven rind. The inside is full of Fruit: it grows all in cloves as big as a small Barly-corn, and these are all full of juice, as an Orange or a Lemon, tho' not growing in such partitions."11 This sounds a little like a citron, although some pomelos, including those not fully ripe, have thicker membranes.

His description of some 'limes' he found in modern Haipan, Vietnam better resemble a typical pomelo. "The Limes of Tonquin are the largest I ever saw. They are commonly as big as

Photo: Wiki User Ananda - Sliced Pomelo (Citrus Maxima)

an ordinary Limon [lemon], but rounder. The rind is of a pale yellow colour when ripe & very thin and smooth. They are extraordinary juicy, but not near so sharp, or tart in taste as the West Indian Limes."12 John Masefield, who edited and commented on Dampier's book, identifies these as "Citrus Decumana (the shaddock) and C. medica"13. Citrus decumana are pomelos (which have a smooth skin) and Citrus medica are citrons (which have rougher skin). So if he is correct, Dampier was probably describing pomelos.

Physician Sloane's description of the pomelos he found on Barbados is even better for the rounder types: "The Fruit is round as big as a Mans Head. The Rind is yellow and smooth, not thick, and the Pulp is very Aromatick... There is a variety or another sort of this with the Pulp and Rind of an Orange colour."14

Regarding the flavor of pomelos, Dampier describes those he found in Banda Aceh as having "a pleasant taste, and tho there are of

Orange Colored Pomelo With Red Interior

them in other parts of the East-Indies, yet these at Achin are accounted the best. They are ripe commonly about Christmas, and they are so much esteemed, that English men carry them from hence to Fort St. George, and make Presents of them to their Friends there."15 Sloane notes that they had "a sweetish sour Tast"16.

Neither the period sailors nor the English botanists discuss the healing or humoral properties of pomelos. Physician Sloane simply describes the fruit without giving any indication that it affected health. Since some authors regarded pomelos as a type of orange, it seems likely that their properties would be similar, but this isn't specifically stated.

Botanist Georg Everhard Rumphius, who worked for the Dutch East India Company in Indonesia, does make an interesting observation somewhat relevant to the health properties of pomelos. "It is ...a marvelous fruit for Sea Journeys, for one can keep diem unspoiled for a long time, as long as they were treated gently when they were taken off the tree, and did not crash onto the ground. They are strung up, and eaten at Sea, where they refresh die stomach and quench one's thirst."17 Sadly, no evidence of this is found in the sailor's books under study. If an example exists from this period, it is probably in a Dutch account.

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 208 & 211; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V2, 1712, p. 15; William Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 23-4, 124-5 & 163; Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement..., 1700, p. 56; Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 67; 2 Georgius Everhardus Rumphius, The Ambonese Herbal, E. M. Beekman, Ed, Vol1, 2011, p. 341; 3 See Nathan Bailey, Universal etymological English dictionary 1724; Elisha Coles, An English Dictionary, 1717; John Kersey, A New English Dictionary, 1713; Edward Phillips, The new world of words, 6th ed, 1706 & John Worlidge & Nathan Bailey, Dictionarium Rusticum, Urbanicum & Botanicum, 1717; 4 Cooke, V2, 1712, p. 15; 5 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 1, 1707, p. 41; 6 Sloane, p. 34; 7 Richard Bradley, The Compleat Fruit and Flower Gardener, 1733, p. 38-9; 8 J. Kumamoto, R. W. Scora, H. W. Lawton and W. A. Clerx. "Mystery of the Forbidden Fruit", Economic Botany, Vol. 41, No. 1, 1987. p. 98-9; 9 Dampier, A New Voyage..., Vol III, 1703, p. 67; 10 Charles Lockyer, An Account of the Trade in India, 1711, p. 177; 11 Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement..., 1700, p. 125; 12 Dampier, A New Voyage..., Vol III, 1703, p. 67; 13 Captain William Dampier, Dampier's Voyages, John Masefield, ed., 1906, p. 576; 14 Sloane, p. 41; 15 Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement..., 1700, p. 125; 16 Sloane, p. 41; 17 Georgius Everhardus Rumphius, The Ambonese Herbal, Vol. 2, 2011, p. 140

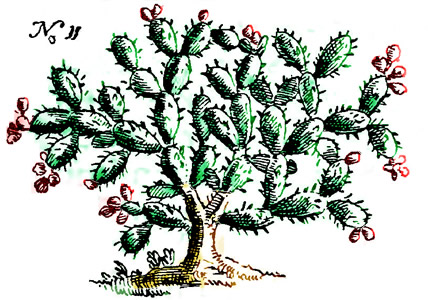

Prickly Pear

(Opuntia)

Called by Sailors: Prickle-pear, Prickled-Pear, Prickly Pear

Appears: 3 Times, in 3 Unique Ship Journeys from 3 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Cabo San Lucas, Mexico; Barbados; Rea Lejo, Nicaragua;

Prickly pears are unusual in that they are described in four different sailors accounts with only two of the descriptions being included in the above count. This is because they are described by buccaneer Lionel Wafer who saw them when he was staying for several months with the Kuna natives in Panama - which is not counted here because it is a land-based account - as well as being found in the French account of French missionary Jean-Baptiste Labat. Only the incomplete English-translation of Labat's books is normally used here, but his description of prickly pear fruit in the original French is most thorough and must not be passed by. Like Wafer, much of his account is land-based.

Buccaneer William Dampier says the prickly pear "is as big as a large Plumb, growing small near the Leaf, and big towards the top, where it opens like a medlar [Mespilus germanica].

Photo: Tomás Castelazo - Prickly Pear Fruit

This Fruit at first is green like the Leaf, from whence it springs with small Prickles

about it; but when ripe it is of a deep red colour. The inside is full of small black Seeds, mixt with a certain red Pulp, like thick Syrup."2 Privateer Edward Cooke describes the fruits shapes as variable with some being "longish and others round at the End of the long, and a little flat on the Top, with several long, sharp Prickles, and many downy Prickles, not unlike the Cow-Itch [trumpet vine - Campsis radicans]."3

Labat's description is a bit more lyrical. "It is green & hard when it begins to appear; it changes color as it grows, it blushes little by little, and finally becomes the color of a lively and dazzling fire when it is quite ripe. ...It is at the point of its maturity that the fruit develops from its center as a bud composed of five leaves, which, in opening, form a species of tulip of an orange color, or of a pale red."4 He accurately suggests the end looks like that of the pomegranate. He then details the fruit's interior. "The inside appears to be filled with small seeds or pips, the outline of which is of a very beautiful crimson red, the inside... is white. These seeds are enveloped in a thick material like jelly of the finest red in the world."5

Regarding the fruit's flavor, Cooke says "the Inside of the round Fruit, is the best, and tastes like our green Goose-berries"6. Dampier comments, "It is very pleasant in taste, cooling, and refreshing".7 Wafer says, "It's a good Fruit, much eaten by the [Kuna] Indians and others."8 As usual, Labat explains the flavor with a flourish, noting it has a "charming taste, mingled with sweetness, with a little hint of sourness, which whets the appetite, gladdens the heart & extremely refreshes."9

Labat provides a detailed explanation of how the fruit was plucked and eaten.

Photo: Center for Disease Control - Prickly Pear Fruit

When you want to pick them without risk of hurting yourself, you have to receive them in a coui [calabash - basically a cup] or other vessel as you separate them from their stem with the knife, after which you take a small slice on each side with the knife, to allow you to grasp the fruit with the thumb, & one of the fingers of the left hand, while with the knife held in the right hand, you remove all the thorn-covered surface. When it is thus cleaned, the skin is cut crosswise, and it is easily detached from the red film [inside], which contains what is good to eat. When the fruit opens by itself, and is beyond its proper maturity, it then has almost no consistency, resembling a liquid jelly, and it is eaten with a cup.10

It is possible that this jelly-like substance inspired Cooke to suggest that the fruit made "very good Sauce boil’d and sweeten’d with Sugar"11. Although enjoyed by sailors, Dampier warns that "if a Man eats 15 or 20 of them they will colour his Water, making it look like Blood. This I have often experienced, yet found no harm by it."12 Labat notes this as well, adding "it does not fail to frighten those who are not instructed in this virtue, believing that they have some ruptured vessel in the body when they see their urine thus colored."13 He adds another warning. "Care must be taken not to let the juice of this fruit fall on the linen, or on the clothes, because it leaves a red stain which never rubs off well, no matter how hard you wash it."14 Physician William Hughes likewise says the juice of the fruit stains the hands and mouth of those who ingest it.15

Of the physicians and botanists used in this article, only physicians Hughes and Hans Sloane talk about the prickly pear. Unfortunately, Sloane focuses on the cactus without saying anything significant about the fruit. Fortunately, the usually terse Hughes talks at length about

Sailor Edward Cooke's Rendition of a Prickly Pear Tree with Fruit (1712)

it. He begins by explaining that, humorally, the fruit cold and moist.16

Medicinally, Hughes says prickly pears are "very good to qualifie thirst, as I have experimented by eating them when I could not come at fresh water"17. He also says that a syrup can be made from prickly pear juice "which hath often been given in Fevers and hot Distempers"18.

Hughes also notes that when sailors are able to eat fresh food, their gluttony (which he calls 'gulosity') causes tumors and apostemes or pus-filled swellings. Because they are not always able to get remedies, "many are driven to make use of what they can meet with: The best, I suppose, for such swellings are these [cactus] leaves; for they are attractive, mollifying, digestive &c.". He advises roasting them until soft and applying them, "and they have wrought effectually, beyond my expectation; yea, better than any preparation that could have been made from a well-furnished [medicine] Chest."19

Not one to miss an opportunity to comment on things he saw, Labat also discusses the medicinal uses of prickly pears with his typical humor. "This fruit is given to the sick, not only because it is very refreshing and very healthy, but also because it seems to cleanse the heart while rejoicing it; however, in whatever state you are, you must eat it with discretion, because when you eat too much of it, it causes a little pain in the base, almost like the slight tingling of hemorrhoids.”20

1 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea, Brazil and the West Indies, 1735, p. 217; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V1, 1712, p. 344; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 222; 2 Dampier, 1699, p. 222-3; 3 Cooke, p. 344; 4 Jean Baptiste Labat, Nouveau Voyage aux Isles de l'Amerique, Tome 4, Translated by the Author, 1724, pp. 342; 5 Labat, p. 343; 6 Cooke, p. 344; 7 Dampier, 1699, p. 223; 8 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of Panama, 1903, p. 99; 9 Labat, p. 343; 10 Labat, p. 344; 11 Cooke, p. 344; 12 Dampier, 1699, p. 223; 13 Labat, p. 345; 14 Labat, p. 344-5; 15 William Hughes, The American physitian, 1672, p. 37; 16,17 Hughes, p. 38; 18 Hughes, p. 39; 19 Hughes, p. 39; 20 Labat, p. 345

Pumpkin

(Cucurbita pepo, C. maxima, possibly C. argyrosperma and C. moschata)

Called by Sailors: Pompions, Pumkins, Pumpkins

Appears: 9 Times, in 4 Unique Ship Journeys from 2 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Tenerife, Canary Islands; Mayo, Cape Verde Islands; Bengkulu, Sumatra; Siumpu Island & Timor, Indonesia; Mindanao, Philippines; Haiphong, Vietnam; Guam; Salvador, Brazil;

Privateer Edward Cooke found pumpkins in March of 1710 on Guam and in May of the same year on Siumpu Island, Indonesia. All the rest of the instances of pumpkins are found in buccaneer William Dampier's accounts. Four of these come from the exploratory voyage to Australia in 1699 (counted here as a buccaneer voyage). Neither Cooke nor Dampier describe the fruit in detail (although Dampier once refers to them as 'ground fruit'2) likely because of the Europeans familiarity with them. So we must rely on the physicians and botanists from around this period to provide insight into pumpkins.

Before proceeding, however, some facts about pumpkins must be explained. Some think pumpkins are a vegetable when they are actually a fruit. This is because they grow from a flower and bear the seeds of the plant inside of them. More specifically, pumpkins are a berry. "Technically

Photo: Suzies Farm - Varieties of Winter Squashes or Potential Pumpkins

defined, a berry is any fruit without a pit that forms from a single flower with a single ovary. Grapes, blueberries, tomatoes, and squashes are all true berries."3

In addition, the word 'pumpkin' may not even refer to the fruit of which we normally think, depending on where you are. "[T]he term 'pumpkin', depending on whether you are in Britain, America, the Caribbean or Australia, may mean either the big orange fruit with a light and watery flesh, or the orange, green, grey, cream, pinky-yellow or multi-coloured and denser fleshed, chestnutty-tasting, fruit that modern Americans and British call winter squash."4

Botanist Louis Lémery identifies three kinds of pumpkins: The First is Cylindrical, and extraordinary both as to Length and Bigness; the second like a Flagon, thick, round and bellied, and the last in the shape of a Bottle, with a Big Paunch, and a narrow Neck". Although he doesn't specify the colors of such pumpkins, he notes that they should have "a white and soft Pulp."5

Physician Hans Sloane likewise describes several pumpkins, calling them by a more proper name, curcubita. The first is the pumpkin familiar in America, which appears in his account of the Caribbean. "[T]he

Shell is yellow, or Cinamon coloured, hard, smooth, shining, having a bitter Pulp within it, and smaller and darker coloured Seeds.

Artist: John Gerard

The Great Long Pumpkin, From The Herball or

General Historie of Plantes, (1636)

One of them is able to contain many Gallons of Melassus, &c. for which they are us'd instead of Bottles."6 (One cannot help but wonder what they did with all that molasses... perhaps make rum?) The second squash he doesn't describe in detail. The last is "like the others, only the round part is no bigger than a Tennis Ball, the Neck being four inches long and crooked."7

Physician John Parkinson takes a different (and more accurate by today's standards) view. "We have but one kinde of Pompion (as I take it) in all our Gardens, not withstanding the diversities of bignesse and colour."8 He and botanist John Gerard both suggest they are a type of melon, which is likewise not far from the truth. Melons are in the family - genus - species Cucurbiticeae Cucumis melo and pumpkins/squashes are Cucurbiticeae Curcubita Pepo. So, while they are not the same (something Gerard suggests in his title "Of Melons or Pompions"9), they are related.

Lémery says that pumpkins are 'fit to be eaten'. He says the most edible are those that are "tender, fresh gathered, light, and with a white and soft Pulp."10 Gerard warns, "The pulp of the Pompion is never eaten raw, but boiled; for so it doth more easily descend, making the belly soluble [loose and open for better digestion]."11 However, he later adds that when they are "boiled in milke and buttered, [it] is ...a good and wholsome meat [food] for mans bodie"12. Parkinson suggests they be "boyled in faire water and salt, or in powdered beefe broth, or sometimes in milke, and so eaten, or else buttered."

Parkinson also provides an interesting recipe,

They use[d to] likewise to take out the inner watery substance with the seedes, and fill up the place with Pippins [a dessert apple], and having laid on the cover which they cut off from the toppe, to take out the pulpe, they bake them together, and the poore of the Cities as well as the Country people, doe eat thereof as a dainty dish.13

Lémery gives a recipe suggestion as well. "They usually mix the Pumpkins with some Aromatick Herbs, such as Parsley, Onions, Mustard, Pepper, and several

![]()

Artist: Ignatz Albrecht

Cucurbita pepo, From Icones plantarum medico-oeconomico technologicarum (1804)

other sharp and volatile things"14. It makes you wish you could have whispered 'nutmeg' in his ear as he was writing. Curiously, Lémery also says that dried pumpkins can be used as flagons. (Your author searched in vain for a dried pumpkin flagon image for this spot.) In addition, every author acknowledges the importance of the pumpkin seed, which was an important ingredient in medicine.

Humorally, Gerard says pumpkins (like melons) "are of a cold nature, with plenty of moisture"15. In his remarks, Lémery agrees with Gerard, mentioning that they 'qualify sharp humors', but he also gives the Paracelsian principles of the fruit, indicating that they "contain much Phlegm, a middling quantity of Essential Salt, and a little Oyl. They agree in hot Weather with Young Bilious People, but Persons of a cold and phlegmatick Constitution ought to abstain from them."16 People, like plants and fruits, were believed to have dominant humoral qualities. Those of a phlegmatic temperament were predominantly cold and wet, which are the same properties Gerard identifies. It was believed that foods with an opposite humoral composition were better suited to people so as to balance their humors.

Artist: John Gerard

The Great Buckler Pumpkin (Some Type of Gourd), From The Herball or

General Historie of Plantes, (1636)

From a health perspective, Gerard said that wild pumpkins had cleansing and purging qualities.17 However, he also says that the cultivated pumpkin "is not well digested; by reason wherof it maketh a man apt and ready to fall into the disease called the Cholericke passion,or Felonie."18 Choleric passion was an illness caused by excess choler, or "acute gastroenteritis occurring in summer or autumn; characterized by severe cramps, diarrhea, and vomiting."19 Lémery advises that pumpkins are "of difficult digestion, weaken the Stomach, and cause Wind and Cholick [blockages in the intestines]." He later says that those which have been preserved by boiling and mixing them with sugar are more wholesome, and so "may be used in Distempers of the Breast, in order to allay the sharpnesses that are there."20

1 Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V2, 1712, p. 15 & 43; William Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 23 & 181; Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 10, 23 & 71; Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 72; 2 Sarah Sietz, "Is Pumpkin a Fruit or a Vegetable? Learn More About This Fall Favorite", cleangreensimple.com, gathered 6/9/2022; 3 Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement..., p. 23; 4 Janet MacDonald, Feeding Nelsons Navy, 2014, p. 37; 5 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 30; 6 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 1, 1707, p. 225; 7 Sloane, p. 226; 8 John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1904, p. 526; 9 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 918; 10 Lémery, p. 30; 11,12 Gerard, p. 921; 13 Parkinson, p. 526; 14 Lémery, p. 31; 15 Gerard, p. 921; 16 Lémery, p. 30; 17 Gerard, p. 922; 18 Gerard, p. 921; 19 "Cholara Morbus", www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, gathered 6/15/22; 20 Lémery, p. 31

Quince

(Cydonia oblonga)

Called by Sailors: Pome-citrons, Pome Cytterens, Quince

Appears: 6 Times, in 6 Unique Ship Journeys from 4 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Almayate, Spain; Madeira, Portugal; Zante, Greece; Santiago, Cape Verde Islands; Comoros; Basra, Iraq;

As with several other fruits found in sailor's accounts, the quince was familiar to most of them because they grew in a variety of places in Europe including England. As a result, none feel the need to describes a quince in any detail. They are occasionally used by sailors of the period to describe other fruit which was unfamiliar to English readers, indicating just how well-known they were to their audience.2

Photo: Susan Fitzgerald - Several Quinces

The only sailor's comment of interest about quinces comes from East India captain Alexander Hamilton, who mentions that at Mocha, Yemen, "they make Store of Marmelade, both for their present Use and Exportation" from a variety of fruits, including quinces, grapes, peaches and apricots.3 He never indicates that sailors consume these marmalades, although his noting their presence makes it seems likely that they did. Fortunately, the books of the physicians and botanists used here supply the lack of information in the sailors' tomes.

French botanist Louis Lémery and English botanist John Gerard both say there are three kinds of quinces.4 Lémery identifies them by size, smell and color without giving their names while Gerard calls them Struthia, Chrysomeliana and Mastela. John Parkinson mentions six different types, noting that "although not many [different types of quinces exist], yet more then our elder times were acquainted with, which shall be here expressed."5 (Normally the fruit discussed is separated here into separate paragraphs about appearance, taste and preparation, but since Parkinson's descriptions of the types of quinces naturally includes all of these aspects, it is quoted here in full.)

Artist: Otto Wilhelm Thomé - Quince, Cydonia oblonga (1885)

The English Quince is the ordinarie Apple Quince... and is of so harsh a taste being greene, that no man can endure to eate it rawe, but eyther boyled, stewed, roasted or baked; all which waies it is very good.

The Portingall Apple Quince is a great yellow Quince, seldome comming to bee whole and faire without chapping; this is so pleasant being fresh gathered, that it may be eaten like unto an Apple without offence.

The Portingall Peare Quince is not fit to be eaten rawe like the former, but must be used after some of the waies the English Quince is appointed, and so it will make more dainty dishes then the English, because it is lesse harsh, will bee more tender, and take lesse sugar for the ordering then the English kinde.

The Barbary Quince is like in goodnesse unto the Portingall Quince last spoken of, but lesser in bignesse.

The Lyons Quince.

The Brunswicke Quince.6

Note that all of these names are tied to Europe, almost certainly by the location where they were found growing. This generally agrees in a broad sense with the locations where the sailors mentioned finding them. It may (or may not) have been the African (Barbary) quince that was found in the Cape Verde Islands. Note also that Parkinson doesn't bother to describe the French or German quince. At present, Wikipedia identifies 24 quince cultivars.7

Gerard gives a general description of quinces, stating that they are all "set with a thinne cotton or freese, and be of the colour of gold, and hurtfull to the head by reason of their strong srnell; they all likewise have a kinde of choking tast: the pulp within is yellow, and the seed blackish, lying in hard skins as do the kernels of other apples."8

Photo: Alice Wiegand - Quince Marmalade

Parkinson notes that some quinces are "greater, others smaller, some round like an Apple, others long like a Peare, of a strong heady s[c]ent, accounted not wholsome or long to be endured, and of no durabilitie to keepe"9.

As food, Parkinson praises the fruit as being "of so many excellent uses... serving as well to make many dishes of meate [food] for the table, as for banquets"10. He goes on to list a few recipes, admitting there are many others inappropriate for his book. "[W]hile they are fresh (and all the yeare long after being pickled up) to be baked, as a dainty dish, being well and orderly cookt. And being preserved whole in Sugar, either white or red, serve likewise"11.

Parkinson also mentions using them to make the marmelade, something sailor Hamilton also suggests in his book. Gerard describes the process. "Take whole Quinces and boile them in water untill they be as soft as a scalded codling or apple, then pull off the skin, and cut off the flesh and stamp it in a stone morter, then straine it... afterward put it in a pan to dry but not to seeth[e] at all, and into every pound of the flesh of quinces put three quarters of a pound of sugar, and in the cooling you may put in rose water and a little muske"12.

From a humoral point of view, Gerard says quinces are cold and dry in the second degree.13 Lémery advises that in the Paracelsian realm, the principles of a quince include "much acid Salt, Oyl and Phlegm. They agree at all Times, to any Age and Constitution, provided they be well Boyled, and taken moderately."14 He also gives some interesting insight into how the Paracelsian principles relate to the flavor of the fruit. Note that in addition to the three active principles (salt, oil and phlegm), there are four elements that are part of Paracelsian theory: earth, air, fire and water. These are the 'terrestrial' or 'earthy parts' that Lémery refers to here.

Artist: John Gerard - The Quince Tree, From The Herball or

General Historie of Plantes, (1636)

The rough and harsh taste of green Quinces proceeds from the strict union there is between their Salts and Sulphurs with the terrestrial Parts; for their active Principles sensibly disengage themselves by the fermentation of the Earthy parts which do detain 'em. Lastly, when full ripe, they retain a harsh taste, because these same earthy parts are in such a manner united to the saline Principles, that they still retain enough for the effecting of that stiptick and harsh taste.15