Fruit in Sailor's Accounts Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Next>>

Fruit in Sailors Accounts During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 6

Fruit Found In More Than One Sailor's Account, Continued

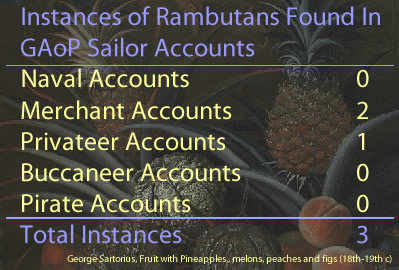

Rambutan

Called by Sailors: Rambostan, Rumbostan,

Appears: 3 Times, in 3 Unique Ship Journeys from 2 Sailor Account.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Jakarta, Indonesia; Malacca & Trenggannu, Malaysia;

Rambutans are native to Malaysia and cultivated in southeast Asia. "Rambutan got its name from the Malay word for hair because the golf-ball-sized fruit has a hairy red and green shell."2 Since it only grows in the East Indies, they only appear in two sailors' books, both of which were sailing near Malaysia. Being unfamiliar to the sailors, both briefly describe the fruit. Even so, little is said of rambutans in the period books and almost nothing is said of their healing properties. The observant Dampier spent a good deal of time in the East Indies, but he never mentions them. As late as 1774, Captain James Cook commented, "This is a fruit little known to Europeans"3. (Although Cook wrote almost fifty years after the golden age of piracy, the author is using his description because there are so few other descriptions of the fruit from around this period.)

When the privateer ship St. George stopped at

Artist: A Bernecker - Rambutan, Nephelium lappaceum, Naturalis Biodiversity Center (1862)

Jakarta in 1705, sailor William Funnell described them in some detail. "The Rumbostan is about the bigness of a Walnut, when the green Peel is off. It is also much of the shape of the Walnut; And has a prety thick tough outer-rind, which is of a deep red; and is full of little knobs of the same colour. Within the Rind is the Fruit, which is quite white, and looks almost like a Jelly: And within the Fruit is a large Stone."4 East India Company sailor Alexander Hamilton, who found the fruit in its native country, gives the fruit a similar, albeit much shorter, nod in his book. "The Rambostan [rambutan] is a Fruit about the Bigness of a Walnut, with a tough Skin, beset with Capillaments [filaments], within the Skin is a very savoury Pulp."5 Cook found the fruit in Jakarta (which he called by the period name Batavia) in 1770. He said it "very much resembles a chesnut with the husk on, and like that, is covered with small points, which are soft and of a deep red colour: under this skin is the fruit"6. Although the two authors who mention the fruit's color say it is red, rambutans can actually have a yellow tint (as seen above) as well a green cast, as Funnell indicates.

Funnell mentions eating the fruit,

Photo: Michael Hermann - Rambutans Growing on Their Tree

although he doesn't discuss the flavor in much detail. "It is very delicate Fruit; and though a Man eat never so much, yet it never does him any harm; provided he swallows the Stones as well as the Fruit:"7 His comment that people didn't eat a lot of the fruit likely refers to its small size as well as the amount of flesh found inside. As Cook explains, "the eatable part ...is small in quantity, but its acid is perhaps more agreeable than any other in the whole vegetable kingdom."8 Hamilton simply states that the fruit contains "a very savoury Pulp."9 Each of these descriptions suggest the fruit tastes good, although they are a little vague. A modern source says that the fruit "is often described as sweet and creamy"10.

The only period health note comes from Funnel, who says that if the seed isn't eaten with the flesh of the fruit, "they are said to cause Fevers."11 This may be related to a fairly common belief than eating too much fruit could cause illnesses, particularly fevers. From a modern perspective, rambutans are high in fiber, copper and vitamin C. So they could actually prevent scurvy if enough of them were eaten.12 However, no one during the period makes this connection.

1 William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 286-7 & Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 381; 2 Julia F. Morton, "Rambutan", Fruits of Warm Climates, 1987. p. 262; 3 James Cook, A New Voyage, Round The World, In The Years 1768, 1769, 1770 And 1771, Vol. II, 1774, p. 212; 4 Funnell, p. 286; 5 Hamilton, p. 381; 6 Cook, p. 212; 7 Funnell, p. 286-7; 8 Cook, p. 212; 9 Hamilton, p. 381; 10 "Rambutan: A Tasty Fruit With Health Benefits", healthline.com, gathered 6/17/22; 11 Funnell, p. 287;12 "Rambutan: A Tasty Fruit..."

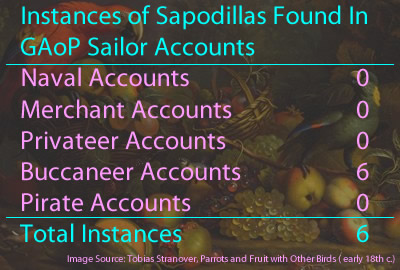

Sapodilla

Called by Sailors: Sapadillo, Sappota, Sapotilla

Appears: 6 Times, in 4 Unique Ship Journeys from 2 Sailor Account.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Jamaica; Isla del Carmen, Mexico; Bocas del Toros & Chepillo

Sapodillas are mentioned five times by William Dampier in four different voyages and once by fellow buccaneer Raveneau de Lussan. Both de Lussan and Dampier found them on Chepillo Island. Dampier also found them in other locations in the West Indies and Central America.

Dampier describes the fruit three times in his books and de Lussan describes two different types in his book. The first time Dampier found them was on the islands of Bocas del Toros in 1681, when he said it "is a sort of Fruit much like a Pear, but more juicy"2. In a later book,

Sapodilla Fruit, Manilkara zapota

he found them while staying with the logwood cutters near what is now Isla del Carmen. There he simply mentioned that the fruits were 'long'3. His fullest description comes from a stop in Panama by the buccaneer vessel Cygnet in 1685. Dampier explained that "the Fruit much like a Bergama-pear, both in colour, shape and size; but on some Trees the Fruit is a little longer... in the midst of the Fruit are two or three black Stones or Seeds, about the bigness of a Pumpkin-seed"4.

Of the two types of Sapodillas de Lussan found in Panama, he says the first "is almost like unto our pears, of a different size, whose rind is greenish, and contains, in the midst thereof, two kernels of an oval form, appearing pretty polished and sleek, and are each of them, in the largest of these fruits, somewhat bigger than an ordinary nut." This is very much like Dampier's last description. He says the second type is much like the first, only "no bigger then a russet pear... and under the rind is of a whitish color."5

Buccaneer surgeon Lionel Wafer found sapodillas on an island off the coast of Panama, which he describes during his stay with the Kuna natives. "It is small as a

Artist: Hans Sloane

Sapodilla Plant, From A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves,

St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2 (1707)

Bergamasco Pear, and is coated like a Russet-Pippin [a russet apple]."6 Since Wafer was staying on the main land with the natives, this instance is not counted in the above numbers. A couple of other travellers also described sapodillas during the period. Mathematician John Taylor, who spent over a year in Jamaica, said the fruit was "about the bigness of a hen's egg, every waie shap't like a date, and being ripe lokes of a gold collour, is covered with a thinn skin."7 Like fellow medical man Wafer, physician Hans Sloane thought it to be the size and color of a russet apple with a rough skin, adding that it contained "several smooth, black Seeds, shining, with a white Slit on one Edge, and within it a pretty hard Shell, containing a white Kernel."8

Dampier thought highly of the sapodilla's flavor calling them "good"9, "very pleasant"10 and "an excellent Fruit"11 Surgeon Wafer said, "The Fruit is very pleasant to the Tast."12 Like Dampier, de Lussan said the first type of Sapodilla he found was "very sweet, and of an admirable taste."13 He added that the flavor of the second type was also 'admirable.' Taylor said the fruit of the sapodilla "concisteth of a soft mellefitious substance, verey gracefull to the pallat... [and is] a verey excellent fruit of great esteem, and hath all the vertues of the date with many more."14

Photo: Wiki User Daderot - Sapodilla Fruit on Tree, Manilkara zapota

The fruit is apparently best when given a chance to continue to ripen after being picked. Sloane says that "within [the fruit is] a sweet, brownish, juicy Pulp... the Fruit it self when Tree ripe[ned], is so full of Milk, as to drop out plentifully when gather'd, and if it be cut there appear little Rills or Veins of Milk, quite thro' the Pulp"15. Dampier gives a more cogent description of this. "When it is green or first gathered, the Juice ['milk'] is white and clammy, and it will stick like glew; then the Fruit is hard, but after it hath been

gathered two or three Days, it grows soft and juicy, and then the juice is as clear as Spring-Water, and very sweet"16.

Sloane is the only one to say anything about how the fruit was consumed. "Their greatest Use is by Way of Dessert as other Fruits, they comending themselves sufficiently to all Pallats by their grateful Taste."17

Curiously, what Sloane does not comment on is the medicinal value of the fruit. He typically culls the works of his fellow physicians and lists them in his book, but here he says nothing about the humoral or health benefits of sapodillas.

1 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 33, 202, 204; Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 48-50 & 94; 2 Dampier, 1699, p. 33; 3 Dampier, 1700, Part 2, p. 49; 4 Dampier, 1699, p. 202-3; 5 Ravaneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 330; 5 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of Panama, 1903, p. 98; 7 John Taylor, Jamaica in 1687, David Buisseret ed, 2010, p. 210; 8 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, 1707, p. 171; 10 Dampier, 1700, Part 2, p. 59; 11 Dampier, 1700, Part 2, p. 49; 12 Dampier, 1699, p. 203; 13 de Lussan, p. 330; 14 Taylor, p. 210-1; 15 Sloane, p. 171; 16 Dampier, 1699, p. 202-3; 17 Sloane, p. 171

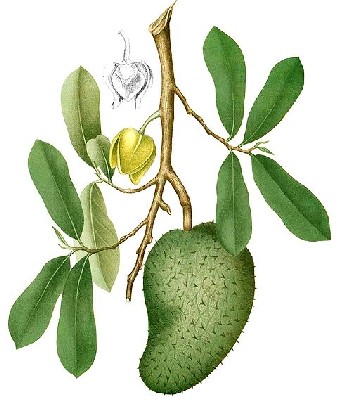

Soursop

Called by Sailors: Sour-sop, Sower Sop

Appears: 2 Times, in 2 Unique Ship Journeys from 2 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Guam; Salvador, Brazil;

Soursops appear in two sailor's accounts from the period, both considered here as buccaneer expeditions. William Cowley mentions finding 'Sower Sops' when they stopped at Guam after crossing the Pacific in 1685. Dampier found them at Salvador, Brazil at the beginning of his exploratory voyage to Australia in 1699. (This is technically not a buccaneer account, but since this is the only exploratory voyage in the sailor's accounts and is made by a buccaneer, it is counted with the buccaneer voyages.)

Dampier and physician Hans Sloane both describe the soursop. Sloan says that the tree "is propagated by the Seed in Jamaica and the Caribes."2 Dampier comments, "This Fruit grows also both in the East and West-Indies.”3 Richard Ligon, half-owner of a sugar plantation in Barbados in the mid-seventeenth century, found it there as well, referring to it as a 'Prickled apple'.

Photo: Muhammad Mahdi Karim - Soursop Fruit (Annona muricata) |

Soursops are described by Dampier as "as big as a Man's Head, of a long or oval Shape, and of a green Colour; but one side is Yellowish when ripe. The outside Rind or Coat is pretty thick, and very rough, with small sharp Knobs; the inside is full of spungy Pulp, within which also are many black Seeds or Kernels, in shape and bigness like a Pumkin-seed."4 Sloane says it is "as big as one's two Fists, being turbinated [conical], of an irregular Shape, large towards the Footstalk, and ending in a Point; it is yellowish green on the Out-side, and cover'd with several small pointed Knobs or Tubercles, blunt and soft"5. Ligon states that the fruit "is shap'd like the heart of an Oxe, and much about that bigness; a faint green on the outside, with many

Artist: Francisco Manuel Blanco

Soursop, Annona muricata, From Flora de Filipinas (c. 1880)

prickles on it"6. English botanist John Ray [Joannis Raii] also gives a description which is similar to that provided by Sloane, adding that "when the fruit falls [from the tree], it pulls out some portion of the pulp, leaving a hole."7

Sloane says that inside the fruit there are "many oblong, roundish, brown Seeds, a little flat, shining, and having within them a white Kernel of the same Shape."8 Ray says, "The seeds are located in lines extending towards the center from the circumference, the size of the bean is oblong, teretiusculae [somewhat rounded], gray, with a ridge extending along its length"9.

Speaking of the flavor, Dampier says the "Pulp is very juicy, of a pleasant Taste, and wholesome."10 Sloane advises that "the Pulp Fruit is as soft as Custards, being, white, juicy, of a sowr and sweet Taste mix'd". He later adds "The Fruit from its Taste is reckon'd one of their pleasantest Fruits11. Ray comments that the pulp is orange colored with "a very pleasing taste"12. Lignon's comment about the flavor is somewhat dubious, suggesting that "the taste very like a mustie Lemon."13

Dampier makes an unusual suggestion for eating soursops. "You suck the Juice out of the Pulp, and so spit it out."14 Sloane's comment is a bit more conventional in this regard. "When they are as yet unripe, and about the Bigness of Turneps, if so dress'd, they eat like them."15 He doesn't comment on how a ripe soursop should be eaten, although he later notes that that people can eat a whole one without any detrimental effects.

Sloane is the only author to discuss the health aspects of soursops. He says the fruit is cooling, although it is not entirely clear if he is referring to the humoral properties of the fruit or just the effect that consuming it had. He doesn't list any properties of the raw fruit's effect on health, but he talks about how it can be prepared for medicinal use. "Of the unripe Fruit press'd is made a Wine which is as clear as Water, and is good for Fluxes and Cankers [ulcers] in Childrens Mouths."16

1 William Ambrose Cowley, "Cowley's Voyage Round the World", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 16; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 67; 2 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol2, 1705, p. 167; 3,4 Dampier, p. 67; 5 Sloane, p. 167; 6 Richard Ligon, A True And Exact History Of the Island of Barbadoes, 1673, p. 70; 7 Joannis Raii, Historiae plantarum tomus tertius, translated by the author, 1704, p. 78; 8 Sloane, p. 167; 9 Raii, p. 78; 10 Dampier, p. 67; 11 Sloane, p. 167; 12 Raii, p. 78; 13 Ligon, p. 70; 14 Dampier, p. 67; 15,16 Sloane, p. 167

Star Apple

Called by Sailors: Cayamite, Star Apple

Appears: 3 Times, in 2 Unique Ship Journeys from 2 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Jamaica; Chepillo Island, Panama

Raveneau de Lussan mentions seeing star apples in Panama, referring to them as 'cayamites' which is a misspelling of the Spanish term for the fruit - caimito.2 Fellow buccaneer William Dampier talks about them twice in his first book. He notes that they were planted by the Spanish in cultivated 'fruit walks' on Jamaica, "but I did never see any [similar] improvement made by the English, who seem in that little curious”3.

Dampier

Photo: Forest and Kim Starr -

Star Apple Fruit (Chrysophyllum cainito)

describes the star apple being "as big as a large Apple, which is commonly so covered with leaves, that a Man can hardly see it."4 However, he admits that he didn't have the opportunity to taste it which may explain why he doesn't provide more detail. de Lussan gives even less information, suggesting it "is like a large damson [plum]"5. Fortunately, physician Hans Sloane found them on Jamaica, where he provides a much more complete description of the fruit. He says star apples are

a purple Fruit, smooth, round, like a large Pippin, or Apple, having a whitish, sometimes purple Pulp like Jelly, with several milky Veins running thro' it... enclosing round the Centre of the Fruit some black, shining, rhomboidal Seeds, having a white Scissure or Slit on one of their Edges, always regarding the Centre, bigger than those of Nisperas [nisperos or loquats, introduced to Europe in the 18th century], each of which is inclos'd in a thin, white Membrane. If the Fruit be cut athwart the Places where the Seeds were lodg'd will represent a Star, whence the Name as well may be derived6.

Not all star fruit is purple, however. Modern botanist Julia Francis Morton says that the fruit is "2 to 4 in (5-10 cm) in diameter, may be red-purple, dark-purple, or pale-green. It feels in the hand like a rubber ball. The

Photo: Judge Florentino Floro - Different Star Apple Colors

glossy, smooth, thin, leathery skin adheres tightly to the inner rind"7. She adds that the fruit can have as many as ten seeds.

de Lussan says that the flavor of star apple fruit is "very savory."8 Dampier mentions that he was told it was good fruit, but since he hadn't tried it, his comments are not from experience. Sloane only said it was "sweet and pleasant enough" and "not very unpleasant"9, which can hardly be taken as complimentary.

Neither Dampier nor de Lussan discuss how the fruit should be eaten. Sloane says, "It is used by Way of Dessert as other Fruits"10, but doesn't give any further details. However, modern botanist Morton provides some insight. "Star apples must not be bitten into. The skin and rind (constituting approximately 33% of the total) are inedible. When opening a star apple, one should not allow any of the bitter latex of the skin to contact the edible flesh. The ripe fruit, preferably chilled, may be merely cut in half and the flesh spooned out, leaving the seed cells and core."11

Medicinally, Sloane only says that the fruit is "wholesome, and of good Digestion."

Photo: Forest and Kim Starr -

Star Apples on Tree (Chrysophyllum cainito)

He also notes that some of his contemporaries suggest it "to be very much provoking to Venery [sexual indulgence]."12 He says nothing about the humoral qualities nor of how it might be used to treat any particular medical conditions. Modern author Morton has more to say about this, however.

The ripe fruit, because of its mucilaginous character, is eaten to sooth inflammation in laryngitis and pneumonia. It is given as a treatment for diabetes mellitus, and as a decoction is gargled to relieve angina. In Venezuela, the slightly unripe fruits are eaten to overcome intestinal disturbances. In excess, they cause constipation. ...A decoction of the tannin-rich, astringent bark is drunk as a tonic and stimulant, and is taken to halt diarrhea, dysentery and hemorrhages, and as a treatment for gonorrhea and "catarrh of the bladder". The bitter, pulverized seed is taken as a tonic, diuretic and febrifuge [anti-fever medicine]. Cuban residents in Miami are known to seek the leaves in order to administer the decoction as a cancer remedy.13

1 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 202 & 204; Raveneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 330; 2 de Lussan,p. 330; 3,4 Dampier, p. 204; 5 de Lussan,p. 330; 6 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, 1707, p. 170-1; 7 Julia F. Morton, Fruits of warm climates, 1987, p. 408; 8 de Lussan,p. 330; 9 Sloane, p. 170; 10 Sloane, p. 171; 11 Morton, p. 410; 12 Sloane, p. 171; 13 Morton, p. 410

Tamarind

Called by Sailors: Tamarind, Tamarins, Tamerin

Appears: 9 Times, in 9 Unique Ship Journeys from 7 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Cape Corso Castle, Africa; Madagascar; Malabar Coast & Surat, India; Java, Jakarta & Timor, Indonesia; Barbados;

Tamarinds had long been available in England by the golden age of piracy; Gerard details their use in the early 17th century. As a result, although period sailor's accounts mention tamarinds, they spend no time describing them. Edward Barlow includes them in a long list of what he called 'good fruits' at Java, Indonesia when the East Indiaman Experiment was there in 1672, but he doesn't provide any other details.2 Tamarinds also appear in the pirate account of Edward England in the General History of the Pyrates,

Photo: Ivar Leidus -

Tamarind fruits (Tamarindus indica)

but it is just the voice of physician John Atkins interjecting some descriptive color into the account of Madagascar and not an actual instance of pirates consuming them.

More interesting is privateer Edward Cooke's inclusion of tamarinds as one of the "Particulars for the Use of the Officers in the great Cabbin of every Ship". Officer's food tended to be a cut above what was served to the before-mast men and, although there was probably less disparity between officer and sailor provisions on privateer ships than in the navy, the fact that Cooke singles it out as officer's food is suggestive. (The other officers foods mentioned by Cooke were fairly basic: "Butter, sweet Oil, Bread or Rusk, Flower... Spelmans Neap [turnips], Cheese, [and] Cape-Wine"3. (Interestingly, Cooke also includes tamarinds in "A List of Commodities brought from the Spanish West-Indies into Europe." when describing the treasure that Woodes Rogers' privateers brought home with them.4)

In a similar vein, William Dampier notes that when the men on the East Indiaman Defence became ill from too much 'salt Provision', "Captain Heath... ordered his own Tamarinds, of

Photo: Aditya Madhav -

Tamarind Seeds and Pulp

which he had some Jars aboard, to be given some to each Mess, to eat with their Rice. This was a great refreshment to the Men, and I do believe it contributed much to keep us on our Legs.

"5 Here again, tamarind had been reserved as officer's food. It is also noteworthy that Dampier mentions their medicinal value. (The medicinal value of tamarinds appears in most of these period accounts.)

The fruit itself is not described by the sailors. Nor do the botanists and physicians under study describe it. Fortunately, mathematician and chemist John Taylor, who was in Jamaica in 1687, does. "This fruite is a small, green, flat fruite, in which is a large stone. These grow many together in a cluster; of the pulp of this fruite is made many sort of excellent concerves good to allay heat in fevers etc."6 Tamarind pulp is the sticky substance which surrounds the seeds in the pod. It can be eaten raw, although this is not specifically noted in the period accounts.7 Notice also that even in his simple description, Taylor finds it necessary to list medicinal uses.

Dampier also describes something he calls 'Wild Tamarind-trees" which he found on Timor during his stop there in 1699 aboard the Roebuck. He explains that they are

Photo: Forest and Kim Starr - Lysiloma latisiliquum Seedpods

not so large as the true; though much resembling them ... The Fruit grows, not on the Branches singly, like those in America, but in Strings and Clusters, forty or fifty in a cluster, about the Body and great Branches of the Tree, from the very Root up to the Top. These Figs are about the bigness of a Crab-Apple, of a Greenish Colour, and full of small white Seeds; they smell pretty well, but have no Juice or Taste; they are ripe in November.8

As Dampier notes, these are not true tamarinds (and this instance is not counted in the numbers above). They are actually Lysiloma latisiliquum, today still called wild or false tamarinds. Their appearance is very much like the true tamarind, Tamarindus indica. However, as their scientific names suggest, the two fruits are not related.

Possibly describing the flavor of a tamarind, John Taylor says it is "a most excellent fruitt, whose pulp preserved is good in many distempers"9. Recall that Edward Barlow similarly said it was a 'good fruit', although, like Taylor's comment, it is not clear whether he meant the flavor.

Their connection to medicine has already been well established, but it is interesting that in the early 17th century botanist John Gerard states that tamarinds are "at this day are a medicine frequently used". Humorally, Gerard says that the "pulpe of Tamarines is cold and dry in the third degree"10. Third degree humoral properties are very strong. Physician Hans Sloane explained that tamarinds were "good to restrain bilious Humours, and cool."11 There are two 'bilious humors' - black bile, which is cold and dry, and yellow bile, which is hot and dry.

Photo: Bruno Navez -

Tamarindus Indica Pods

Medicinally, physician John Pechey advised that tamarinds "correct the Acrimony [bitterness] of the Humours, purge Choler [yellow bile] and restrain the Heat of the Blood; they cure Fevers, and the Jaundice, and take off the Heat of the Stomach and Liver, and stop Vomiting."12 The 'Heat of the Blood' he mentions refers to the notion that blood (one of the four humors) could become overheated, causing it to degrade and 'putrify' leading to illness. Indeed, several of the illnesses Pechey describes were caused by heat, something which a third degree cooling effect would be perceived as useful in treating. Jaundice was said to be caused by yellow bile permeating the body13, so a medicine which purged such humors would be employed. The drying faculty would be seen as helpful for stopping vomiting.

Gerard also cites a number of medicinal recommendations by other medical authors. He explains that tamarinds could be "used in all putrid fevers, caused by cholericke [yellow bile] and adust [black bile] humors, and also against the hot distempers and inflammations of the liver and reines [kidneys], and withal against the Gonorraea." Here again we have see the ties to purging bile to cure fevers, cooling 'hot distempers' and drying (presumably) to cure gonorrhea. Gerard continues, "Some also commend them against obstructions, the dropsie [edema or swelling], jaundise, and the hot distempers of the spleene: they conduce also to the cure of the itch [scabies], scab, leprosie, tetters [red, irritated skin], and all such ulcerations of the skin which proceed of adust humors [black bile]."14 The ties between medicine and humor theory are very apparent in these descriptions.

Physician Hans Sloan makes one more comment loosely related to the medical vertues of tamarinds which must be included here. "The Pirates in Guzarate [Gujarat, India] make the Merchants they take in Prizes drink salt Water and Tamarinds to make them void their Pearls and Gold, that they [out of] Fear swallow'd."15

1 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 217; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 211 & 467-8; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V2, 1712, p. 60; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 520; Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 69; Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 130; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 178; Nathaniel Uring, The Voyages and Travels of Captain Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 106; 2 Barlow, p. 211; 3 Cooke, p. 520; 4 Cooke, p. xvii; 5 Dampier, 1699, p. 520; 6 John Taylor, Jamaica in 1687, David Buisseret ed, 2010, p. 211; 7 Santosh Singh Bhadoriya, Aditya Ganeshpurkar, Jitendra Narwaria, Gopal Rai & Alok Pal Jain, "Tamarindus indica: Extent of explored potential", Pharmacognosy Reviews, January-June 2011, Vol. 5, Issue 9, p. 74-5; 8 Dampier, Part II, 1703, p. 689; 9 Taylor, p. 190; 10 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1607; 11 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol 2, 1705, p. 45; 12 John Pechey, The Compleat Herbal, 1707, p. 336; 13 Paulus Aegineta, The Medical Works of Paulus Aegineta, Vol. 1, 1834, p. 324; 14 Gerard, p. 1608; 15 Sloane, p. 46

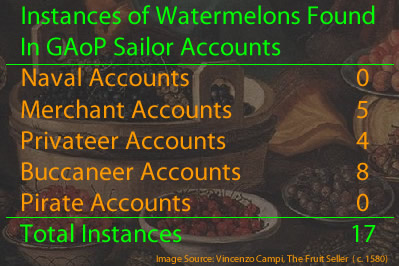

Watermelon

Called by Sailors: Water-melon

Appears: 17 Times, in 11 Unique Ship Journeys from 6 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Marseilles, France; Mayo, Sao Vincente & Santiago, Cape Verde Islands; Cape of Good Hope, Africa; Malacca , Malaysia; Banda Aceh, Timor, Indonesia; Mindanao, Philippines; Guam; Barbados; Salvador & St. Catherine, Brazil; La Libertad, Ecuador

Watermelons have reasonably good support in the period sailor's accounts, although they don't rate much descriptive text. More than half of the instances of watermelons found in the sailors' accounts come from William Dampier, who mentions finding them 10 different times. There is also a pirate connection to watermelons, although it has nothing to do with consuming them and is not included in the above numbers. When pirate John Halsey died in Madagascar in 1708, Charles Johnson reported, "His Grave was made in a Garden of Water Melons, and fenced in with Pallisades to prevent his being rooted up by wild Hogs, of which there are Plenty in those Parts."2

Although the period sailors don't provide much information about watermelons, some other period authors do. Dutch West India Company Merchant William Bosman talks about the watermelons that were cultivated by the company officers on the Dutch gold coast of Africa in the late 17th century.

Artist: Giovanni Stanchi

Watermelons and Pears (c. 1645-72)

Note that the unusual hollow swirls shown in these watermelon don't

have

anything to do with

the genetic makeup of the melon. See the paragraph below.

"The immature and yet small Water-Melon is white within and green without; but when ripe its green Coat is speckled with white, and its internal whiteness somewhat intermixed with red; and the more it participates of the latter [the redder it is], it is by so much the riper and more agreeable"3. Botanist John Gerard, who considered watermelons to be the same fruit as pumpkins and melons, describes what he calls a 'Virginia watermelon'. "[T]he fruit is of a very blackish greene colour, and extendeth it selfe in length neere foure inches, and three inches broad, no bigger nor longer than a great apple... containing a substance, pulp, and flat seed like the ordinary Pompion"4. Physician William Hughes, who toured English Caribbean estates while serving on a privateer ship in 1651, said some watermelons were "in shape like unto our middle-siz'd Pumpions, and as big; the substance within them spungy, tender... and being cut, is something mixed with white and red"5. Physician Hans Sloane, talking about the watermelons he found during his travels in the new world in 1687, identified two varieties of them. "This [the watermelon] is commonly planted here [Jamaica], and is of two sorts, that with whitish green, and that with red Pulp, the Seeds of the latter being red, those of the first black."6

These descriptions all mention a large amount of white matter in some watermelons, something seen in the above image.

Photo: Wikimedia User Downtowngal -

An Immature Watermelon Half

This does not indicate a separate type of watermelon as Sloane suggests. Nor does it suggest how watermelons used to look at this time as some otherwise reputable websites indicate.7 Rather it shows how watermelons such as those in the image 1) may have not not been properly pollinated and 2) are likely immature.

The 'holes' in the swirls seen in the above image are a problem called hollow heart disorder in watermelons. Fruit and vegetable specialist Gordon Johnson of the University of Delaware ran an experiment in 2014 which "showed that increasing the distance from a pollen source increased the incidence of hollow heart and reduced flesh density."8 Examples of watermelons with hollow heart disease, including some which look remarkably like those in the above painting can be seen in this article. The unusual amount of white flesh is suggests the watermelons shown may be immature. All watermelons have white flesh, particularly at the outside edges, but in watermelons which have not yet fully matured, it can be found deeper in the fruit. (See the image at left.) The watermelons in Stanchi's painting are probably not at all representative of watermelons in the seventeenth century, just those with the problems indicated. However, such an artistic pattern would likely appeal to an artist doing a still life of fruit.

Regarding the flavor of watermelons, Bosman says they are second only to pineapple. He says the are "very

delicious, watry, refreshing and cooling."9 Hughes agrees, calling the watermelon "a very excellent fruit... well tasted... it is very moist

Artist: Giorgio Bonelli -

Watermelon Plant (1772-93)

and waterish."10 When Dampier's buccaneer ship Batchelor’s Delight was in Ecuador in 1684, he noted that their "Water-Melons... are large and very sweet.."11 After transferring to the buccaneer ship Cygnet, Dampier and arriving in Guam in 1686, he noted that the island had "many Water-melons... here being a very excellent Fruit"12. He appears to have been a fan.

As food, they were clearly eaten raw. Bosman says, "When green it is eaten as Salade, instead of Cucumbers, to which it is not wholly unlike"13. On the other end of the meal plan, Sloane said that watermelons in the Caribbean were "used here by way of desert, are very much commended and every where planted"14. Several authors note that watermelons were cultivated, indicating their value as food.

From the perspective of medical humors, Gerard (again, lumping them in with pumpkins and melons) says, "All the Melons are of a cold nature, with plenty of moisture"15. Hughes agrees, stating that watermelons are 'naturally very cold and moist', adding that the fruit "must be very moderately eaten, otherwise it is very apt to cause a Fever, by cooling the stomack too much, and spoiling digestion"16. According to humor theory, digestion occurred in four stages, the first being that which happened in the stomach, which produced chyle. This was then processed in the second stage by the liver, producing bodily humors. Too much heat or cooling spoiled the process, producing 'bad' humors that led to illness.

Medicinally, Sloane said watermelons were "Diuretick, counted very good in Fevers, extremely good against hot Livers, and Kidnies, very cooling, and therefore often eat[en] with Wine."17 Their perceived cooling property would have been useful in each of these health conditions according to the medical understanding of the time. Even merchant Bosman recognized that their cooling ability made them "proper for a Feverish Person "18. Sloane adds, "The Seeds are us'd for Emulsions, and provoke to Sleep."19 Gerard seizes upon the diuretic quality, noting that "they have a certain clensing qualitie by means whereof they provoke urine, and do more speedily passe through the body than doe either the Gourd, Citron [lemon], or Cucumber"20. Physician Hughes doesn't have a lot to say about their specific use in medicine, but adds an unusual observation. "This fruit ...quencheth thirst, as I have often made tryal, and hath sometimes caused me to faint, as the drinking cold water hath done, by too much chilling or condensing the Spirits of a sudden."21

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 270 & 312; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V2, 1712, p. 9; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 134, 303 & 311; Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 124-5 & 163; Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 23, 33 & 71; Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 56 & 72; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 22; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 5 & 293-4; Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 25-6, 27; 2 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 470-1; 3 William Bosman, A New and Accurate Description of the Coast of Guinea, 1705, p. 304; 4 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 919; 5 William Hughes, The American physitian, 1672, p. 22-3; 6 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol 1, 1705, p. 226; 7 See for examples, Helen Thompson, "This Renaissance Painting of Fruit Holds a Modern-Day Scientific Lesson", smithsonian.com, gathered 8/26/22; Daniel Choi, "Why Watermolons Look Different in Old Paintings", historyofyesterday.com, gathered 8/26/22; & Shirin Jaafari, "In the 17th century, watermelons looked vastly different from what we eat today", theworld.org, gathered 8/26/22; 8 Adam Thomas, "Saving Watermelons", udel.edu, gathered 8/26/22; 9 Bosman, p. 304; 10 Hughes, p. 22-3; 11 Dampier, 1699, p. 134; 12 Dampier, 1699, p. 302; 13 Bosman, p. 304; 14 Sloane, p. 226; 15 Gerard, p. 921; 16 Hughes, p. 23-4; 17 Sloane, p. 226; 18 Bosman, p. 304; 19 Sloane, p. 226; 20 Gerard, p. 921; 21 Hughes, p. 24