Fruit in Sailor's Accounts Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Next>>

Fruit in Sailors Accounts During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 2

Fruit Found In More Than One Sailor's Account

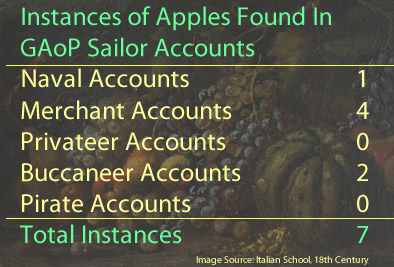

Apple

(Malus domestica)

Called by Sailors: Apple

Appear: 7 Times, in 7 Unique Ship Journeys from 6 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Cadiz, Spain; Livorno, Italy; Tenerife, Canary Islands; Basra, Iraq; Coquimbo and Valdiva, Chile; Pisco, Peru

Apples were very familiar to the European sailor (as they are to us today) so little is said about them in the sailor's accounts.

In describing them, botanist John Gerard says "Apples do differ in greatnesse, forme, colour;

Apples, From The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed,, By John Gerard (1636)

and taste; some covered with a redde skinne,others yellow or greene, varying infinitely according to the soyle and climate, some very great, some little, and many of a middle sort; some are sweet of taste, or something soure, most be of a middle taste between sweet and soure, the which to distinguish I think it impossible"2 Although his description is rather vague, it is also fairly accurate. Botanist John Parkinson, who frequently lists the various types of fruit in his book, concurs with Gerard, adding that there "are so many, and infinite almost as I may say, that I cannot give you the names of all...

and I thinke it almost impossible for any one, to attaine to the full perfection of knowledge herein, not onely in regard of the multiplicitie of fashions, colours and tastes, but in that some are more familiar to one Countrey then to another"3. He goes on to list 54 different apples, among which are the bastard queen, the leather coat, the cowsnout, the cat's head and the woman's breast. (Of the last, he simply says it "is a great apple."4) It should come as no great surprise that none of these names are still in use today. Today, it is estimated that there are over 7,500 different types of apples.5

French military Engineer Amedee-Francois Frezier is the only sailor to give any kind of description of apples, mentioning them twice in his journey in South America

Making Cider, From A Treatise on Cider, by John Worlidge (1678)

on various ships. He notes that in Valdavia, Chile, "the Want of Wine may be supply'd with [hard] Cyder, as in some Provinces of France; there is such a Multitude of Apple-Trees, that there are little Woods of them."6 It is notable (but not really surprising), that the only description of apples from the period sailors accounts have to do with turning them into an alcoholic beverage. Cider was a popular drink with some naval officers and appears in some of the pirate accounts as well.

Apples in the sailor's accounts are primarily found in temperate latitudes where they grow well. In Basra, Iraq, references to apples go back at least to the second century B.C and the death of queen or priestess Puabi whose tomb contained pendants with "stylized depictions of clusters of apples, dates, and date inflorescences. Apples and dates are both associated with the goddess Inanna,who is associated with love and fertility."7

From a medical perspective, Herbalist John Gerard identified apples as having cold and moist humoral properties. He adds, "They do easily and speedily passe through the belly, and therefore they doe mollifie the belly, especially being taken before meat [food]."8 Parkinson says apples are "of very good use in Melancholicke diseases [those arising from an excess of the humor black bile], helping to procure mirth, and to expell heavinesse." He also says that an ointment called pomatum is made from apples "which is much used to helpe chapt lips, or hands, or for the face, or any other part of the skinne that is rough with winde, or any other accident, to supple them, and make them smooth."9

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 163, William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 10; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, pp. 44 & 186, Alexander Hamilton, British sea-captain Alexander Hamilton's A new account of the East Indies, 17th-18th century, 2002, p. 78, Jean-Baptiste Labat, The Memoirs of Pére Labat 1693-1705, 1970, p. 262, Basil Ringrose, The Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp, And Others, in the South Sea, 1684, p. 41; 2 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1458; 3 John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1904, p. 586; 4 Parkinson, p.588; 5 "Apples and More", University of Illinois Extension Website, gathered 7/27/2022; 6 Frezier, op. 44; 7 Naomi F. Miller, " Symbols of Fertility and Abundance in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, Iraq", American Journal of Archaeology 117 (2013), p. 127; 8 Gerard, p. 1460; 9 Parkinson, p. 589;

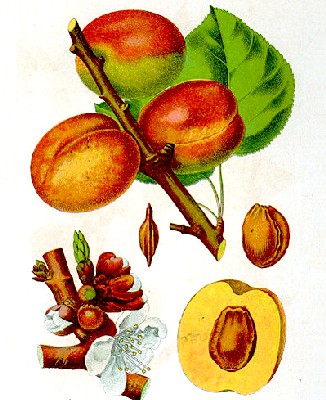

Apricot

(Prunus america & Prunus armeniaca)

Called by Sailors: Apricot, Apricott, Apricock

Appear: 7 Times, in 7 Unique Ship Journeys from 6 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Aden and Mocha, Yemen; Basra, Iraq; Tenerife, Canary Islands; Chepillo Island, Panama; Coquimbo, Chile

Apricots originated in Asia and spread throughout the world from there, so it is not surprising that they appear in the accounts of sailors traveling in the the East Indies. However, they were also quite familiar to Europeans. English herbalist John Gerard states in his Herball first published in 1597 that apricot trees "grow in my garden [located in Holborne], and now adaies in many other gentlemens gardens throughout England. "2 They were brought to South America well before the golden age of piracy. Buccaneer Basil Ringrose notes that "delicate Gardens" of them could be found in Chile in 16803, where they had been cultivated by Spanish settlers.

Artist: Jan Mortel - Still Life with Apricotes and Butterflies (1683)

Likely due to their familiarity with the fruit, the period sailors did not spend any time describing them in their books, simply mentioning them in their lists of foods found in various locations. So we must rely on the botanists for a period description of this fruit. Gerard says "the fruit round like a Peach, yellow within and

without, in which doth lie a browne stone nothing rough at all as is that of the Peach, shorter also and lesser, in which is included a sweet kernell."4 French botanist and chemist Louis Lémery suggested there were three different types of apricots,

the first of which are pulpy, almost round, grow as big as a small Peach, flat on the sides; one of which is of a dark Red, and the other Yellowish. The pulp is tender, pleasant, and of a good smell: It contains a very hard and flat Stone, wherein there is a bitter Kernel: The second differs from the first, in that they are of a more whitish Colour, and that the Kernel is sweet. Lastly, the third are smaller than the others, but not so well tasted, and of a yellowish colour.5

Botanist John Parkinson lists six different types of apricots in his book, calling them the great, small, white, Mascoline, long Mascoline and Argier [Algerian].6 Note that these

Artist: Johann Georg Sturm

Apricot, Prunus armeniaca, From Dutchschlands Flora (1796)

names are no longer in use. Today there are at least 67 varieties of apricots, according to homestratsosphere.com.

Parkinson believed that an apricot was "without question a kinde of Plumme, rather then a Peach, both the flower being white, and the stone of the fruit smooth also, like a Plumme"7. Lémery says that apricots have "an agreeable taste, and [are] used more for pleasure than Health"8.

In discussing the use of apricots as food, Parkinson wrote in 1629

Apricockes are eaten oftentimes in the same manner that other dainty Plummes are, betweene meales of themselves, or among other fruit at banquets.

They are also preserved and candid [candied], as it pleaseth Gentlewomen to bestowe their time and charge, or the Comfitmaker [candy-maker] to sort among other candid fruits.

Some likewise dry them, like unto Pears, Apples, Damsons [a type of plum], and other Plummes.9

Lémery suggests that apricots are preserved "to render them more pleasing to the taste, and that they may keep the longer."10 Preservation by drying would have made it possible for apricots and the other fruits listed to be carried on ships, but they were probably seen as an unnecessary luxury for an average sailor's diet.

Gerard suggests they are humorally cold and moist in the second degree.

Photo: Karunakar Rayker - Apricots on Tree in Nubra Valley, India

Lémery, who uses the Paracelsian explanation of elements says apricots "contain an indifferent quantity of Oil and essential Salt; and much Phlegm."11 He warns that "People ought to be cautious of this sort of Food, which contains a viscous and thick Juice, and sometimes at the very first passages [of the intestines], causes Wind, and crude Humours." However, when discussing the preservation of apricots, Lémery notes that this makes them "less obnoxious [to health], because their viscous Phlegm is rarified by the Sugar and Boiling." He believes the sugar preserves and thus blocks the "oily and embarasing parts naturally contained within them"12.

Medicinally, Gerard says apricots, "are ...most wholsome to the stomack and pleasant to the taste, yet doe they ...putrifie and yeeld but little nourishment, and... [are] full of excrements [unwanted matter]. Being taken after meat [food] they corrupt and putrifie in the stomack; being full eaten before meat they easily descend, and cause other meats to passe down the sooner"13. Lémery says the pits are useful for killing worms.14 Parkinson cites Italian physician Pietro Mattioli as recommending "the oyle drawne from the kernels of the stones [pits], to annoint the inflamed haemorrhoides or piles, the swellings of ulcers, the roughnesse of the tongue and throate, and likewise the paines of the eares."15

1 Francis Rogers. Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, Bruce Ingram, ed., 1936, p. 174, Basil Ringrose, The Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp, And Others, in the South Sea, 1684, p. 41, Raveneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 330; Alexander Hamilton, British sea-captain Alexander Hamilton's A new account of the East Indies, 17th-18th century, 2002, pp. 52 & 78, William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 10 and Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 283; 2 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1449; 3 Ringrose, p. 41; 4 Gerard, p. 1448; 5 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 14; 6,7 John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole, Paradisus Terrestris, Reprinted from the Edition of 1629, 1904, p. 579; 8 Lémery, p. 15; 9 Parkinson, p. 579-80; 10 Lémery, p. 15; 11 Gerard, p. 1449;12 Lémery, p. 15; 13 Gerard, p. 1449; 14 Lémery, p. 15; 15 Parkinson, p. 580

Avocado

(Persea americana)

Called by Sailors: Avocat, Avogato-Pear, Albecatos, Palta (Peru)

Appear: 5 Times, in 4 Unique Ship Journeys from 4 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Hiloe, Chile; Tabago; Chepillo Island, Panama; Peru; Jamica, French West Indies

Avocados appear to have originated in Central America, most likely Mexico. Buccaneer William Dampier explains that there are avocados "still in Jamaica in those Plantations that were first settled by the Spaniards, as at the Angels, at 7 Mile Walk, and 16 Mile Walk. There I have seen these Trees which were planted by the Spaniards, but I did never see any improvement made by the English, who seem in that little curious."2 Physician William Hughes likewise found them "in divers places in Jamaica; and the truth is, I never saw [them] elsewhere"3. Amedee Frezier noted that they are found in the French Caribbean Islands.4

They generated quite a bit of interest among various authors who spent time at sea during this period resulting in a variety of descriptions of this fruit. Dampier's states that an avocado is

Artist: Amanda Almira Newton (1916)

"as big as a large Lemon. It is of a green colour, till it is ripe, and then it is a little yellowish. ... The Substance in the inside is green, or a little yellowish, and as soft as Butter. Within the Substance there is a Stone as big as a Horse-Plumb."5 Frezier says that the fruit contains "a round Kernel, somewhat pointed, of the Consistence and Bulk of a Chesnut, but of no other Use than a Musk Colour Dye: The Substance that incloses it is greenish, and almost as soft as Butter"6. Physician Hughes indicates that it looks like a fig, "but very smooth on the out-side, and as big in bulk as a Slipper-Pear [possibly referring to the prickly pear]; of a brown colour, having a stone in the middle as big as an Apricock, but round, hard, and smooth: the outer paring or rinde is... a kind of a shell, almost like an Acorn-shell... yet the middle substance... is very soft and tender"7.

Dampier suggests that the fruit has no flavor, recommending that it be combined with other foods to give it flavor.8 Frezier says it tastes something like butter "with a Mixture of that of a Hazle-Nut"9. Hughes says it is "one of the most... pleasant fruits on the Island [of Jamaica]"10, without really describing the taste. In the original French editions of his book, the ever descriptive french priest Jean-Baptiste Labat says the inner fruit "melts by itself in the mouth... the taste it has ... is quite close to that of a beef marrow pie."11

Photo: Bruno Navez

Avocado Fruit (Persea americana

Dampier warns that avocados "are seldom fit to eat till they have been gathered two or three Days; then they become soft, and the Skin or Rind will peel off."12 According to buccaneer Raveneau de Lussan, "This fruit must be fully ripe, and very soft, before it becomes good food, and then it is that you find the pulp of it as white as snow. The Spaniards eat it with spoons, as we do cream, and indeed the taste thereof is mostly the same."13 Anyone who has tried to eat an unripe avocado will readily understand these comments.

Because of the light flavor of avocados, a number of suggestions about what should be added to make them more palatable were given. Frezier first recommends simply salting them, later suggesting that they also go well with sugar and lemon juice.14 Labat notes, "Some people put it on a plate with sugar & a little rose water, & orange blossoms."15 Physician Hans Sloane, who found avocados on Jamaica, says an avocado can be eaten as dessert "with Juice of Lemons and Sugar to give it a Piquancy"16.

Of course, this is not quite what we generally expect of avocado consumption. Dampier advises that because to the lack of flavor, "‘tis usually mixt with Sugar and Lime-juice, and beaten together in a Plate; and this is an excellent Dish. The ordinary way is to eat it with a little Salt and a roasted Plantain; and thus a Man that’s Hungry, may make a good Meal of it."17

Photo: Nikodem Nijaki - A Great Idea is a Great Idea... In Any Time Period

Here we begin to see the roots of guacamole. Even more suggestive, Hughes recommends that "the Pulp being taken out and macerated (softened by mashing) in some convenient thing, and eaten with a little Vinegar and Pepper, or several other ways, is very delicious meat (food)."18

Physician Sloane doesn't identify any humoral properties, probably because the fruit was relatively unknown among the European medical community. . He does explain, "This is accounted one of the wholesomest Fruits of these Countries... supporting Life it self. It is useful not only on these Accounts to Men, but likewise to all Manner of Beasts."19 This refrain is repeated by some of the sailors. Frezier says avocados are "very wholsome, and good for the Stomach"20. Dampier advises, "It is very wholsome eaten any way."21 Physician Hughes agrees, although he phrases it differently. "[I]t nourisheth and strengtheneth the body corroborating the vital spirits, and procuring lust exceedingly"22.

That last comment cannot be simply passed by without explanation. Several other authors mention this curious aspect attributed to avocados, although, unlike Hughes, they report it second-hand. Frezier notes, "they say it is a Provocative to Love."23 Dampier says "It is reported that this Fruit makes to Lust, and therefore is said to be much esteemed by the Spaniards"24. Where did the avocados' prurient reputation come from? For the answer, we must look to the Nuhuas, the people indigenous to Central America. "Ahuacatl was the Nahuatl word for "testicle," an apparent testament to the avocado's appearance when growing in pairs, and nod to its supposed properties as an aphrodisiac."25 One suspects the properties followed the appearance, not the other way around.

1 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 202 & 204, Bartholomew Sharp, "Captain Sharp's Journal of His Expedition," A collection of original voyages, William Hacke, ed., 1993, p. 33, Raveneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 330; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 172-3; 2 Dampier, p. 204; 3 William Hughes, The American physitian, 1672, p. 41; 4 Frezier, p. 172; 5 Dampier, p. 203; 6 Frezier, p. 172; 7 Dampier, p. 203; 6 Frezier, p. 172; 7 Hughes, p. 40-1; 8 Dampier, p. 203; 9 Frezier, p. 172; 10 Hughes, p. 41-2; ;11 Jean Baptiste Labat, Nouveau Voyage aux Isles de l'Amerique, Tome 1, Translated by the author, 1724, p. 343; 12 Dampier, p. 203; 13 de Lussan, p. 330; 14 Frezier, p. 172; 15 Labat, p. 343; 16 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, 1725, p. 133; 17 Dampier, p. 203; 18 Hughes, p. 42; 19 Sloane, p. 133; 20 Frezier, p. 172; 21 Dampier, p. 203; 22 Hughes, p. 42; 23 Frezier, p. 172; 24 Dampier, p. 203; 25 Brian Handwerk, "Holy Guacamole: How the Hass Avocado Conquered the World", Smithsonian Magazine (Online), gathered 2/25/22;

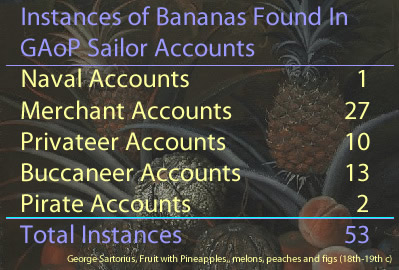

Banana

(Musaceae musa)

Called by Sailors: Banana, Bonano, Bonanoe

Appears: 53 Times, in 29 Unique Ship Journeys from 16 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Madeira, Portugal; Santiago & Sao Vincente, Cape Verde Islands; Principe; Cape Corse Castle, Africa; Cabinda, Angola; St. Helena, Cape of Good Hope, South Africa; Ile de la Selle, Comoros Islands; Magascar; Mocha, Yemen; Bombay, Goa, Karwar, Malabar Coast, Surat & Thalassery, India; Sri Lanka; Jakarta, Malacca, Malaysia; Banda Ace, Java & Sumatra, Indonesia; Timor, Indonesia; Bengkulu, Sumatra; Batanes and Mindanao, Philippines; Guam; Aboyna Cay & Haiphong, Vietnam; Saba, Barbados; St. Vincent, Antilles; Dutch West Indies; Cape Grace a Dios & along the Rico Coco, Honduras; Chepillo Island, Panama, Elsewhere on the Isthmus of Panama, Gulf of Nicoya, Costa Rica; Salvador & St. Catherine's Island, Brazil; Hiloe, Chile; La Palma, Panama; Pisco, Peru; Atacames, Ecuador; Salahonda, Columbia

Bananas are

Photo: Judge Floro - Latudin Banana, Philippines

one of the most often mentioned fruits in sailor's accounts from this period, probably in part because they were found in so many places and were cultivated by so many people. Sailor William Funnell notes that "in most parts of the East and West-Indies there is great plenty of them."2 Based on the number of sailors who described and commented upon bananas, they appear to have been quite interested in this fruit. Naval and Merchant Sailor Edward Barlow mentions finding them in twelve different places on six different voyages. They are even found in the pirate accounts of Howell Davis and Edward England, although the information is part of the background information written by sea surgeon John Atkins rather than an indication that the pirates ate bananas.3 (It is almost certain that they did, however.)

While at Gorgona Island, off the coast of Columbia in July of 1709, Privateer Edward Cooke said that bananas grew "below the [plant's] Leaves upon a great Stalk, in a Bunch of 50 or 60"4, a description of which he includes a drawing of in his book (seen at left.)

Artist: William Funnell

Banana Tree, From A Voyage Round the World (1707)

Sailor William Funnell reported that the fruit was similar in appearance to plantains - having an outer yellow cod and being white on the inside. However, while plantains were "about eight or nine Inches long... the Bonanoe [is] not above six."5 Buccaneer William Dampier estimated that Bananas were half the size of plantains, "being also more mellow and soft, less luscious"6. In opposition to the others, physician Hans Sloane notes that bananas are "less coveted for food" than plantains on Jamaica.7

As food, bananas were suggested to be a possible substitute for bread. Cooke says, "Sometimes this Fruit is eaten instead of Bread, as are the Plantans, which are much of the same Nature, but larger and dryer."13 Atkins similarly says in the General History of the Pyrates that bananas are "eat[en] at Meals instead of Bread"14. In his own book, Atkins explains that bananas "are roasted and eat[en] as Bread."15. Dampier mentions that they are used as bread "in many places of America [referring to the Caribbean and the Colonies]."16 However, he also says that bananas don't serve the role of bread nearly as well as plantains.17

Artist: Albert Eckhout

Bananas, goiaba e outras frutas (17th c.)

A sort of proto banana smoothee appeared in the sailor's accounts. The process is described by physician William Hughes. "When they are full ripe, the Planters peel them, and macerate [mash and soak] the meat, either alone or with boiled Potatoes and water, &c and make a very good drink thereof."18 Physician Hans Sloane says this drink can be made from either bananas or plantains with the same result. "[W]hen ripe,

their Pulp being mash'd with Water till it comes to the Thickness of

Honey, it works and clears it self, the thick swimming at the Top, and

the thin Drink drawn out of a Tap at the Bottom of the Troughs it's

made in. This Drink is in Use all over these hot Parts of the West-indies"19. However, Dampier suggests that bananas were suited for "making Drink oftner than Plantains, and it is best when used for Drink"20.

Although Sloane describes bananas, he doesn't say anything at all about their potential uses in medicine. However, surgeon William Hughes advises that a banana "is excellent good both for meat [food] and medicine; good for the Reines [reins - kidney region], Kidneys, and to provoke Urine; and it is said to nourish the childe in the Womb: but being immoderately eaten, it oppresseth the stomack"21. He adds that "although they are said to be purging to some [referring most likely to the idea that they 'provoke urine'], yet they are also good against a Flux, and that a Dysenteria, as I my self have made tryal."22 Yet he also warns that if too many bananas are eaten in one sitting "it oppresseth the stomack... [and is] provoking to Venery [sexual indulgence]"23. Like the avocado that last idea may have something to do with the shape of the fruit.

1 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 26; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal, 1934, pp. 86, 186, 188, 199, 208, 211, 312, 372-3, 375, 431, 467-8 & 480-1; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V1, 1712, p. 316-7; Cooke, A Voyage..., V2, 1712, p. 15; William Ambrose Cowley, "Cowley's Voyage Round the World", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, pp. 2-3 & 15-16; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, pp. 311 & 426; Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 23-4, 124-5, 163 & 181, Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement..., p. 5, Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 66-7 & 72, Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 79; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, pp. 22, 172-3 & 186; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 5, 60-2, 150-1, 267-8, 286-7 & 293-4; Daniel Defoe [Charles Johnson], A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, pp. 130 & 185-6; Jean-Baptiste Labat, The Memoirs of Pere Labat, 1693-1705, John Eadon ed, 1970, p. 100; Raveneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 329, 330, 357, 364 & 457; Sieur de Montabon, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 476; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, pp. 178, 191 & 233; Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 25-6; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p 54; Nathaniel Uring, The Voyages and Travels of Captain Nathaniel Uring, 1928, pp. 11 & 12; Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of Panama, 1903, p. 97; 2 Funnell, p. 61; 3 Atkins writing in Defoe [Johnson], p. 130 & 185; 4 Cooke,p. 164; 5 Funnell, p. 61-2; 6 Dampier,1699, p. 316; 7 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, 1707, p. 147; 8 Cooke,p. 164; 9 Francis Rogers, p. 158; 10 Funnell, p. 62; 11 Dampier,1699, p. 316; 12 Atkins, p. 48; 13 Cooke,p. 164; 14 Atkins writing in Defoe [Johnson], p. 187; 15 Atkins, p. 48; 16 Dampier, 1700, Part 1, p. 23; 17 Dampier, p. 316; 18 William Hughes, The American physitian, 1672, p. 75; 19 Hans Sloane, p. 142; 20 Dampier, p. 316; 21 Sloane, p. 147; 22 Hughes, p. 75; 23 Hughes, p. 76; 24 Hughes, p. 75-6

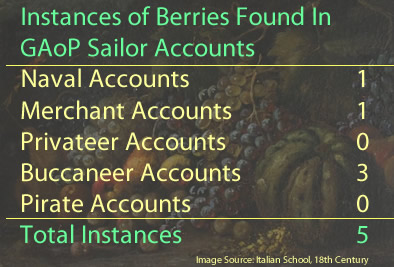

Berries

Called by Sailors: Berries, Blackberries, Gooseberries, Juniper, and Strawberries

(Rubus rubus, Ribes, Juniperus, Frangaria ananassa)

Appears: 5 Times, in 5 Unique Ship Journeys from 4 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Alexandria, Egypt; Sulawesi, Indonesia; Sierra Leone, Africa; Chepillo Island, Panama; & Coquimbo, Chile

The term 'berries' is a bit of a cheat because it is used here as a catch-all category for various berries common to England which were mentioned in the European sailors' descriptions of

Photo: Øyvind Holmstad - A Mixed Berry Selection

their travels. As a result, the instances discussed here include several types of berries.

Those included here are only briefly mentioned as being available in various places where the sailors stopped. The lack of description probably arose because the berries they found were as familiar to the sailors then as they are to us today. Taking a cue from the sailors, the more familiar berries will not described in any detail here. However, those berries which were discussed in greater detail or which were of interest because of their uniqueness to Europeans have been given their own entries.

Surgeon John Atkins only uses generic term 'berry' to describe the fruit he found when HMS Swallow was in Sierra Leone in 1721.2 William Dampier similarly found some unidentified berries when his ship Roebuck touched at in Ceram (Sulawesi, Indonesia) in April of 1700.3 Because of their lack of any detailed information, it is impossible to say exactly what type of berries either found.

Fortunately, some of the sailors were a little more specific. Historian Peter Earle cites the records of the merchant vessel Viner Frigott which he said found blackberries while spending a week in Alexandria, Egypt in the late 1670s.4 Basil Ringrose notes that buccaneer captains John Cox in the Mayflower and Bartholomew Sharp in the Trinity found "Strawberries, Gooseberries, and other Fruit" in Coquimbo, Chile in 1680.5

Photo: Wiki user newt - Gooseberries in a Cup

(Note that the term 'gooseberry' is itself used somewhat nonspecifically to refer to various berries from the ribes genus.) Buccaneer Raveneau de Lussan include juniper berries in a list of fruits he found on Chepillo Island, Panama when Laurens de Graaf's ship Neptune stopped there in May of 1685.6

As with many of the fruits discussed here, it is possible that something which looked like a familiar fruit found in a foreign country may have been something else entirely. In his book of traveling in the West Indies, physician Sloane, who viewed plants with more precision than the average sailor, discusses unidentified "Sort[s] of Trees which are very numerous, having Leaves of Canella, or Malabathrum, (wild cinnamon) elegantly nervous, and a coronated Fruit which comes nearest to a Gooseberry of any European Fruit I remember."7 (Here again, keep in mind the vagueness of the term gooseberry.) Without further information on what they were, however, no definite conclusion about what he saw can be drawn, however.

From a health perspective, each berry had its own properties. Herbalist John Gerard said that unripe blackberries "do very much dry and binde witthall: being chewed they take away the heate and inflammation of

the mouth,and almonds of the throat [tonsils]:

Artist: John Gerard

Stone Blackberry Bush, from The Herball or

General Historie of Plantes (1636)

they stay [stop] the bloudy flix, and other fluxes, and all manner of

bleeding". He adds that they also heal "eies [eyes] that hang out, hard knots in the fundament [anal canal], and stay the hemorrhoides"8. He later adds that ripe blackberries are 'not unpleasant' to eat.

Gerard says that strawberries are of a cold and moist humor. They "quench thirst and do allaw [allay] the inflammation or heate of the stomacke: the nourishment which they yeeld is little, thin, and waterish"9. This last comment refers to the creation of humors in the body by processing food, something for which he indicates strawberries have little or no use. However, he goes on to state, "The ripe Strawberries quench thirst,coole heate of the stomack and inflammation of the liver, [and] take away, if they be often used, the rednesse and heate of the face."10

Gerard identifies gooseberries as having a cold and dry humor.11 Botanist John Parkinson says that 'ordinary' gooseberries "while they are small, greene, and hard, are much used to bee boyled or scalded to make sawce, both for fish and flesh of divers sorts, for the sicke sometimes as well as the sound, as also before they bee neere ripe, to bake into tarts, or otherwise... They are a fit dish for women with childe to stay their longings, and to procure an appetite unto meate [food]."12 Gerard says they are like other berries, stopping bleeding and binding the stomach.13

Gerard says the humors of juniper berries are hot and somewhat dry, although not as dry as the tree itself. Medicinally, "[t]he fruit of the Juniper free doth clense the Liver and kidnies... it also makes a thin clammy and grosse humors. It is used in countrepoisons and other wholsome medicines: Being over largely taken it causeth gripings and gnawings in the stomack, and maketh the head hot... it provoketh urine."14

1 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 48-9; Peter Earle, Sailors English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775, 1998 p. 88; William Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 164; Raveneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 330; Basil Ringrose, The Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp, And Others, in the South Sea, 1684, p. 41; 2 Atkins, p. 48; 3 Dampier, p. 164; 4 Earle, p. 88; 5 Ringrose, p. 41; 6 de Lussan, p. 330;7 Sloane, p. 75; 8 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie fof Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1274; 9 Gerard, p. 998; 10 Gerard, p. 999; 11 Gerard, p. 1324; 12 John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1904, p. 561; 13 Gerard, p. 1325; 14 Gerard, p. 1373

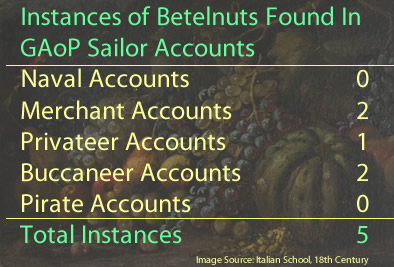

Betelnut

(Areca)

Called by Sailors: Areca Nuts, Aresah, Betel-Nuts

Appear: 5 Times, in 5 Unique Ship Journeys from 3 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Goa, India; Haiphong, Vietnam; Mindanao, Philippines; Guam, Salvador, Brazil

Areca palm fruit is a bit unusual because many of those who consumed them weren't interested in the flesh of the fruit, they were after the seed found inside. This seed is typically referred to as betel nut and is a stimulant drug.2 It contains alkaloids which release adrenaline when chewed, producing a burst of energy or, in some people, a feeling of well-being.3 Several of the sailor's accounts mention them, often describing its use by natives of the East Indies rather than suggesting the sailor used it.

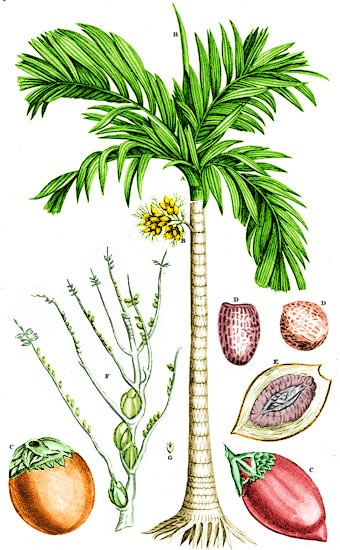

Georg Eberhard Rumphius, a German botanist, categorized the plants he found

Artist: Georg Eberhard Rumphius

'Areca Palm with Nutmegs', From Herbarium Amboinense (1741)

in the Ambon archipelago while employed by the Dutch East India beginning in 1654. He explains that "the outer shell is fibrous, semi-thick, white, and juicy and made up of several firm fibers, which become soft" as it matures. When fully ripe, "the shell is dried up and fibrous, unsuitable for eating"4. He identified two different types of this fruit: the white pinanga and the black pinanga. The white pinanga is "about the size of a duck's egg, or a large chicken's egg, long and round like the fruit of an apple; if it remains on the tree for a long time, it is orange, the shell of this species is very soft, and has very delicate fibers"5. The black pinanga is "about the size of a chicken egg, long and round... externally green, intermixed with a little white at the top, when ripe becomes more red"6.

Edward Cooke found them when the privateer Dutchess stopped at Guam in March of 1710. He said that the seed was "inclos'd in a Case or Husk, like the

Photo: Forest and Kim Starr

Areca Vestiaria Fruit on the Tree, Tropical Gardens of Maui-Maui

Coco-Nut, about as big as a Nutmeg, and not unlike it when cut."9 This description makes the fruit sound hard and dry something Rumphius noted happened when it remained on the tree too long. Dampier explained that when the merchant ship Curtane was in Vietnam, areca fruit was "most esteemed when it is young, green, and tender; for 'tis then very juicy. At Mindanao also they like it best green: but in other places of the East Indies it is commonly chew'd when it is hard and dry."10 Lastly, surgeon John Fryer rather lyrically describes the fruit he found at Madras (modern Chennai), India in 1673. He explained that the tree brought "forth from its pregnant Womb (which bursts when her Month is come) a Cluster of Green Nuts, like Wallnuts in Green Shells, but different in the Fruit; which is hard when dried, and looks like a Nutmeg."11

Dampier, who appears to have tasted the fruit at Brazil, says that it is "somewhat tart, yet pleasant and very wholsom"12. Rumphius noted that before the fruit was ripe, it contained "a small cavity in which there is a small amount of sweet liquid", but he added that "if it is eaten alone, it is ungrateful". He said that once the fruit ripened, "it is yellow and almost red on the outside, the shell is dried up, it is fibrous and unsuitable for eating"13. Speaking specifically of the 'white pinanga', he explains "The flavor of this Pinanga is not so austere, nor does it quickly inebriate or cause anxiety like the black fruit; In green [not yet fully ripe] nuts the shell is softer and more suitable for eating. There is also another variety, which is called Pinang Boubou, or scented, because it gives off a sweet aroma during eating, almost like fresh rice"14.

Several authors discuss how the seeds are prepared by various natives. While visiting the Philippines, Dampier talked about preparing betelnuts when the fruit was not yet fully ripe. "Their way is to cut it in four pieces, and wrap one of them up in an Arek-leaf, which they spread with a soft Paste made of Lime or Plaster, and then chew it altogether.

Photo: Wiki User Ffggss - Betel Nut Prepared and Wrapped for Use

Every Man in these parts carries his Lime-box by his side, and dipping his Finger into it,

spreads his Betel and Arek-leaf with it."15 Once ripe, however, Dampier says "then they cut it only in two pieces with the green Husk or Shall on it."16 This method seems to have been used all over the East Indies. Fryer describes a similar process used by the people in Madas as does Cooke for those at Guam. Fryer notes that the lime is "Chinam (Lime of Calcined Oyster Shells)".17

Dampier reported trying betelnut chewing while at Mindanao. He said that "sometimes it will cause great Giddiness in the Head of those that are not us'd to chew it. But this is the Effect only of the old Nut, for the young Nuts will not do it."18 Fryer commented, "If swallowed, it inebriates as much as Tobacco."19 Dampier later added that "it was exceeding juicy, and therefore makes them [the Filipinos] spit much. It tastes rough in the Mouth, and dies the Lips red, and makes the Teeth black"20.

Humorally, Rumphius says that areca "has the power to contract quite strongly, to dry and slightly cool,

Photo: Steve Evans

The Effect of Chewing Betelnut on the Teeth

as indicated by the tart taste."21 Medicinally, Dampier said it "maybe eaten by sick People."22 Cook suggests it was "reputed by the Natives, and all that use it, an excellent Preservative against the Tooth-ach and Scurvy, most of them being free from rotten Teeth, tho' of a great Age."23 Dampier similarly said that although betel nut turns teeth black, "it preserves them, and cleanseth the Gums. It is also accounted very wholsom for the Stomach"24. Rumphius is a little more scientific in his description of the medicinal qualities of areca nut, which he calls pinang.

Against diarrhea and bloody flux one takes a daily dose of half a quint (about four grams) of crushed old Pinang, with red tart wine, chalybeated water [mineral water containing iron], or cooked-rice water ...which both binds and strengthens the intestines, the same Pinang cooked in white wine or water, and held in one's mouth, firms up the teeth, and dries the cathars [cavities?] that were caused by them: one also mixes it with drying salves for scabies; and the common man believes that Pinang-chewing will give him good teeth well into old age, though this is not borne out by experience, for one commonly sees heavy Pinang-eaters who are toothless at quite an early age25

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 493; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, Vol 2, 1712, p. 15; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 311; Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 23-4; Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 69-70; 2 "Betel Nut", Australian Alcohol and Drug Foundation website, gathered 5/1/22; 3 "How Dangerous is Betelnut?", healthline.com, gathered 6/23/22; 4 Georg Eberhard Rumphius, Herbarium Amboinense, 1741, translated by the author, p. 27; 5,6 Rumphius, p. 29; 7 Dampier, 1703, p. 69; 8 Dampier, 1699, p. 318; 9 Cooke, Vol 2, p. 15; 10 Dampier, 1700, Part 1, p. 24; 11 John Fryer, A New Account of East India and Persia, 1698, p. 40; 12 Dampier, 1703, p. 69; 13 Rumphius, p. 27; 14 Rumphius, p. 29; 15 Dampier, 1699, p. 318-9; 15 Dampier, 1699, p. 319; 17 Fryer, p. 40; 18 Dampier, 1699, p. 318; 19 Fryer, p. 40; 20 Dampier, 1699, p. 319; 24 Georgius Everhardus Rumphius, The Ambonese Herbal, E. M. Beekman, Ed, Vol1, 2011, p. 235; 22 Dampier, 1703, p. 69; 23 Cooke, Vol 2, p. 21-2; 24 Dampier, 1699, p. 319; 25 Rumphius, Vol. 1, p. 235

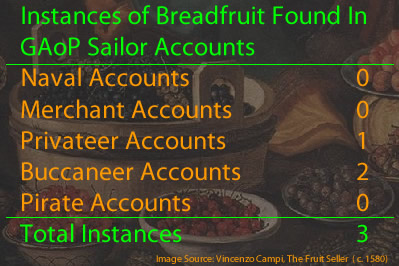

Breadfruit

(Artocarpus altilis, Artocarpus mariannensis & Pandanus Tectoris)

Called by Sailors: Bread Fruit, Dukduk, Melory Fruit, Rima

Appears: 3 Times, in 3 Unique Ship Journeys from 2 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found: Guam & Great Nicobar Island, India

Breadfruit is found in two of the sailor's accounts from this period. William Dampier encountered them aboard the buccaneer ship Cygnet in the late 1680s. He mentions breadfruit twice, once in 1686 when they stopped at Guam and then in 1688 when they were in the Nicobar Islands, India. He suggests they are two different fruits, calling the one in Guam 'bread fruit' (Artocarpus altilis) and the other in the Nicobar Islands, 'melory fruit' (Pandanus tectorius aka Nicobar breadfruit). These two fruits are from different genera; however, they share similar properties2 as well as colloquial names so both have been included here. In addition to Dampier, privateer Edward Cooke, captain of one of Woodes Rogers' ships, identified two types of breadfruit he found at Guam, calling one 'Rima' (from the Filipino word rimas,

Photos (from top): Hans Hillewaert, JB Friday

and Forest and Kim Starr

Comparison of Three 'Breadfruits' Mentioned Here

Top: Dampier's Guam Breadfruit, Cooke's Rima

Middle: Cooke's Ducdu, Bottom: Dampier's Melory Fruit

most likely Artocarpus altilis) and the other 'Dukduk' (Artocarpus mariannensis or, locally, 'dokdok'). Like many of the fruits in this article, these are just two different species of the same genus. Each of these three fruits can be seen in the image at right.

Of the breadfruit he saw on Guam (Artocarpus altilis), Dampier says: "The Fruit grows on the boughs like Apples: it is as big as a Pennyloaf, when Wheat is at five Shillings the Bushel. It is of a round shape, and hath a thick tough rind. When the Fruit is ripe, it is yellow and soft"3. Breadfruit can be as large as 18 inches long and 12 inches in diameter.4 (An interesting aspect of Dampier's description is that the penny loaves sold in England varied in size based on the current price of wheat.) Cooke says that the rima, most likely the same breadfruit as Dampier found on Guam is "as big as a Man's Head, of a Date Colour when ripe, and a rough Outside". He states that the the dukduk (Artocarpus mariannensis) breadfruit is similar to the rima, although it is "more oblong, and has about 14 or 15 Kernels in it, about as big as a Chesnut"5.

Dampier's report of the Nicobar melory fruit is somewhat different. "It is shaped like a Pear, and hath a pretty tough smooth Rind, or a light green Colour. The inside of the Fruit is in Substance much like an Apple; but full of small Strings, as big as a brown Thread."6

Of the flavor of the Guam breadfruit, Dampier says, "it is ...sweet and pleasant."7 He goes on to explain that it consists "of a pure substance like Bread: it must be eaten new, for if it is kept above 24 Hours, it becomes dry, and eats harsh and choaky; but ‘tis very pleasant before it is too stale."8 Of the Nicobar fruit, Dampier simply says, "It looks yellow, and tastes well"9. Cooke doesn't comment of the flavor of the breadfruits he found, other than to mention that the two types of breadfruit tasted similar when roasted.

Both authors discuss how the breadfruits they found at Guam were to be prepared. Cooke says that breadfruit can be "boil'd or bak'd, [and] is us'd instead of Bread, and serves the Natives for six Months, Cut in Slices, and dry'd in the Sun, it eats like Bisket (twice baked bread)"10. Dampier says the Guam natives "gather it when full grown, while it is green and hard; then they bake it in an Oven, which scorcheth the rind and make it black: but they scrape off the outside black Crust, and there remains a tender thin Crust, and the inside is soft, tender and white, like the Crumb of a Penny Loaf." He adds that during the eight Months of the Year when it is growing on Guam; "the Natives eat no other sort of Food of Bread-kind."11

Dampier's melory fruit was prepared differently, again indicating that it was not the same thing as the breadfruits found on Guam. He explained that Nicobar islanders have large earthen "Pots they fill with the Fruit; and putting in a little Water, they cover the Mouth of the Pot with Leaves, to keep the steem while it boils. When the Fruit is soft they peel off the Rind and scrape the Pulp from the strings with a flat stick made like a Knife; and then make it up in great lumps, as big as a Holland Cheese; and then it will keep six or seven Days."12

Artist: John Gerard

Stone Blackberry Bush, from The Herball or

General Historie of Plantes (1636)

Dampier reports having a steady supply of breadfruit at the places where he found it. While the buccaneering vessel Cygnet was at Guam, the governor there "sent an order to the Indians that lived in a Village not far from our Ship, to bake every day as much of the Bread-fruit as we did desire... and [they] brought off the Bread-Fruit every day hot, as much as we could eat."13 At Nicobar, "We had then a great Loaf of Melory which was our constant Food... Thus we lived till our Melory was almost spent; beings still in hopes that the Natives would come to us, and sell it as they had formerly done."14

Neither of these two accounts mention the health properties of bread fruit and none of the English botanical or pharmaceutical books used contain an entry for it. This is not surprising giving the newness of it's discovery by the European community. However, German botanist George Eberhard Rumphis, who made a study of plants in Indonesia while working for the Dutch East India company from 1662 through around 1674, provides a little insight. He says the seeds "have a dry and costive nature... and are used by the common folk everywhere to fill the stomach; ...but it is not fit for tender folks, because it will stuff and burden the stomach too much, and cause bloating"14

1 Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V2, 1712, p. 15; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 302 & 488; 2 Shigeyuki Baba, Hung Tuck Chan, Mio Kezuka, Tomomi Inoue & Eric Wei Chiang Chan, "Artocarpus altilis and Pandanus tectorius: Two important fruits of Oceania with medicinal values", Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture; Al-Ain, Vol. 28, Issue 8 (Aug 2016), gathered from proquest.com 5/18/22; 3 Dampier, p. 296; 4 Julia F. Morton, Fruits of warm climates. 1987, p. 50; 5 Cooke, p. 21; 6 Dampier, p. 478; 7 Dampier, p. 296; 8 Dampier, p. 297; 9 Dampier, p. 480; 10 Cooke, p. 21; 11 Dampier, p. 297; 12 Dampier, p. 480; 13 Dampier, p. 302; 13 Dampier, p. 488; 15 Georgius Everhardus Rumphius, The Ambonese Herbal, E. M. Beekman, Ed, Vol1, 2011, p. 356

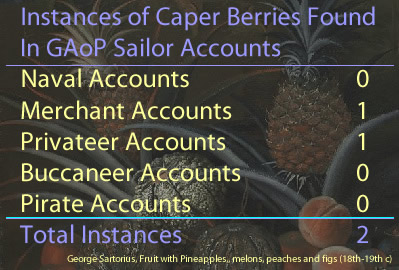

Caper Berry

(Capparis spinosa)

Called by Sailors: Capers

Appears: 2 Time, in 2 Unique Ship Journey from 2 Sailor Account.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Marseilles, France; Guam

Sailor Edward Barlow includes capers as one of the products of Marseilles, France when the Marey Gould stopped there in 1675. He noted that "they transport such as will keep."2 When not at war with each other (and, to a degree, even when they were), France exported desirable products to England where they found a ready market. While captain of the Marquis prize ship in Woodes Rogers privateering fleet, Edward Cooke noted that caper berries were found "in abundance" at Guam in March of 1710.3 Neither author has much else to say about them, however.

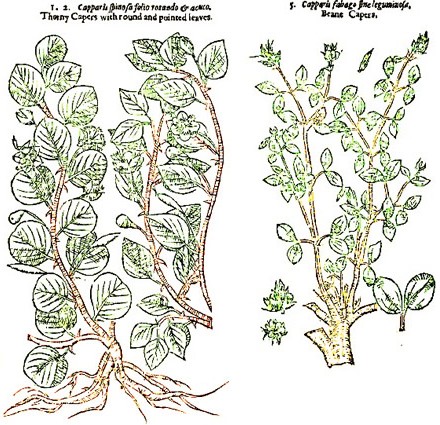

Herbalist John Gerard says that caper berries grow in 'hot regions' including Italy and Spain. He describes the berry as "a smal fruit long and round like the Cornell berry,of a brown colour."4 Fellow herbalist John Parkinson identifies five different types of caper plants. He says the first two differ primarily in the type of leaf they have - one round, the other pointed. Their fruit "is long and

Parkinson's Caper Plants 1, 2 and 5 From Theatricum Botanicum (1640)

round like unto an Olive or Acorne when it is ripe ...wherein are contained divers hard browne seede somewhat like unto the kernells of Grape"5. The third type he calls 'Egyptian Capers without thornes', the fruit of which he says is larger than the other two. The fourth are Arabian capers, which have fruit "greater and larger then the last Egyptian kinde, the fruit being of the bignesse an Egge, or Wallnut with divers seeds therein". The last type are 'Beane capers' which have fruit "somwhat long and round,and opening into severall parts, wherein is contained small brownish seede[s]"6.

The flavor of the ripened 'fruit' is not often described because it is not what what was most often eaten. However, Parkinson mentions that what he calls Arabian capers are "of a sharp and biting taste"7. Presumably, the other four types follow suit, although this is not stated.

The key to understanding capers is understanding how they are normally prepared. As Parkinson explains, the unripened buds of the plant before they form into a fruit are processed into what most people think of when talking about capers. These buds "being ...gathered and pickled up with great salt, are kept in barrells and brought into other countries, and are taken out of the salt afterwards and kept in Vinegar to be spent at the table as all know"8. Physician Louis Lémery describes the best sort of capers as "green, tender [and] well pickled"9. In using them, Gerard explains, "They are eaten boiled (the salt first washed off) with oile and vineger, as other sallads be, and somtimes are boiled with meat."9

Photo: Wiki user Clematis - Caper Fruit Opened (Capparis Spinosa)

Gerard simply lists the humoral property of prepared capers as hot without indicating that the properties of the ripened fruit are the same.10 Parkinson says the pickled buds "doe a little clense the bowells of flegme [phlegm, one of the humors] sticking to them"11. From a Paracelsian perspective, Lémery says they "contain much essential Salt and a little Oil."12 He also warns that if eaten to excess, they over 'rarirfy' [dilute] the Humors.

Medicinally, capers share many health properties with other berries Gerard explains, "They stir up an appetite to meat [food], are good for a moist stomack, and stay the watering thereof, clensing away the flegme [phlegm - one of the bodily humors] that cleaveth unto it. They open the stoppings of the Iiver and milt [spleen]: with meat [food] they are good to be taken of those that have a quartan Ague [fever - most likely malaria] and ill spleens."13 The spleen and liver were believed to be integral parts of processing food into humors which the body could use. Parkinson notes that caper plants "contrasteth, thickneth and bindeth", even when applied outwardly, being particularly useful in treating hardness of the spleen along with other swellings.14 Lémery says capers help with asthma and obstructions of the intestines, kill worms (in the stomach) "and increase the Seed."15

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 272 & Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V2, 1712, p. 15; 2 Barlow, p. 272; 3 Cooke, p. 15; 4 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie fof Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 896; 5 John Parkinson, Theatrum Botanicum the Theater of Plants, 1640, p. 1023; 6 Parkinson, p. 1024; 7 Parkinson, p. 1024; 8 Louis Lémery, A treastise of foods in general, 1704, p. 56; 9,10 Gerard, p. 896; 11 Parkinson, p. 1024; 12 Lémery, p. 56; 13 Gerard, p. 896; 14 Parkinson, p. 1024; 15 Lémery, p. 56

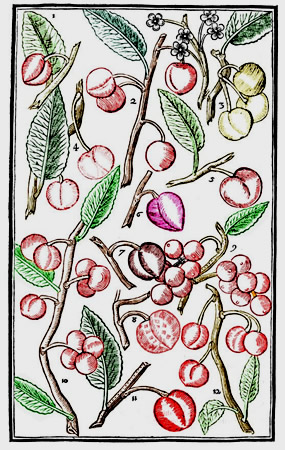

Cherry

(Prunus & Eugenia uniflora)

Called by Sailors: Cherries

Appears: 2 Times, in 2 Unique Ship Journeys from 2 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Tenerife, Canary Islands & Coquimbo, Chile

Buccaneer Basil Ringrose found cherries in Coquimbo, Chile where Captains John Cox of the Mayflower and Bartholomew Sharp of the Trinity stayed for four days. He said the cherry trees were planted in orchards by the Spanish.2 Dampier mentions them in a list of fruits available at Tenerife in the Canary Islands in January of 1699 on his way to Australia.3 Beyond noting their presence in these places, these authors say no more, likely because cherries would have been instantly familiar to an English audience.

Cherry Varieties, From Paradisi in Sole Paradisus

Terrestris,

by

John Parkinson, p. 573 (1629)

Key: 1. May Cherry, 2. Flanders Cherry, 3. White Cherry,

4. Great Leafed Cherry, 5. Luke Wards Cherry, 6. Naples

Cherry 7. Heart Cherry, 8. Big-name or Spotted Cherry,

9. Wide Cluster Cherry, 10. Flanders Cluster Cherry,

11. Archduke's Cherry, 12. Dwarfe Cherry

Botanist John Parkinson begins his entry on the fruit, "There are so many varieties and differences of Cherries, that I know not how to express them unto you, without a large relation of there several formes."4 He goes on to list 36 of them in his first book, and adds 7 more in his second.5 Botanist John Gerard, who admittedly drew upon Parkinson's work, lists 12 different types of cherry.6 Today, one website estimates there are over a thousand types of cherries grown in the United States alone, although this likely includes many cultivars which didn't exist during the golden age of piracy.7 Cherries are members of the genus prunus. Today there are several of subgenera for cherries including Cerasus, which includes fruits typically called cherries, Microcerasus or bush cherries and Padus.8 The period authors primarily focus on the fruit from the first sub-genera, although some of the other subgenera are also suggested.

Parkinson describes the 'typical' English cherry as "red when they are through ripe, of a meane bignesse... with a hard white stone within it"9. Gerard says that cherries "be round,hanging upon long stems or footstalks, with a stone in the middest which is covered with a pulp or soft meat"10. Physician Louis Lémery is a bit more inclusive, dividing them into "red ones... the most common of any... [along with] Red, White or Black Cherries, that are bigger than the [red ones], and of a more compacted Pulp, called a hard Cherry; and lastly, there are small wild black cherries"11. Parkinson and Gerard similarly talk about other-colored cherries including different shades of red, white, black and amber in their discussions of the individual varieties they discuss.

Today, cherries are broadly divided into sweet and sour flavors. The period physician and botanist authors hint at this, although their distinctions are a little less clear. Parkinson says that the red fruits are generally "of a pleasant sweete taste, somewhat tart withall... whose

Photo: Holger Krisp- Cherry Fruit

kernall is somewhat bitter, but not unpleasant."12 In talking about the particular types of cherries, Parkinson and Gerard indicate when they find different varieties to be more or less sweet and tart. Lémery suggests that when selecting cherries to eat, they should be "ripe, juicy, big, plump; and well tasted"13. He elsewhere notes that red cherries have a 'sharpish' taste.

The various authors indicate cherries can be eaten raw once ripe. As Parkinson puts it, "All these sorts of Cherries serve wholly to please the palate, and are eaten at all times, both before and after meales."14 Gerard adds, "Many excellent Tarts and other pleasant meats [foods] are made with Cherries, sugar, and other delicat spices, whereof to write were to small purpose."15

The humoral aspect of cherries is discussed by all three authors mentioned. Gerard advises, "Generally all the kindes of Cherries are cold and moist of temperature, although some [are] more cold and moist than others"16. Parkinson only mentions that they have a cold temperament, "the sower more then the sweete"17. Lémery uses the Paracelsian principles to describe the fruit, explaining that "they have more Phlegm in them than any other Principle, a little Oil, and a little essential Salt."18 He advises cherries "are unwholesome either unto moist and rheumaticke bodies, or for unhealthie and cold stomackes."19

Medicinally, Gerard says

Artist: Osias Beert - Still life with cherries (early 17th c.)

The best and principall Cherries be those that are somewhat sower: those Iittle sweet ones which be wild and soonest ripe be the worst: they contain bad juyce, they very soone putrifie [rot], and doe in gender ill bloud [one of the bodily humors], by reason whereof they do not onely breed wormes in the belly, but trouble some agues [malarial fevers], and often pestilent fevers: and therefore in well governed common wealths it is carefully provided that they should not be sold in the markets in the plague time.20

Gerard also notes that black cherries are better than red cherries because they strengthened the stomach. More generally, Lémery explains that cherries "keep the Body open, quench thirst, cool, create an appetite, are Cordial, and resist Poison. They provoke Urine, and are reputed good for the Diseases of the Head."21 However, he also warns that they "easily corrupt in the Stomach, they also cause Wind and Chollick"22.

1 Basil Ringrose, The Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp, And Others, in the South Sea, 1684, p. 41; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 10; 2 Ringrose, p. 41; 3 Dampier, p. 10; 4 John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1904, p. 571; 5 See Parkinson, Paradisi.... pp. 571-4 and Parkinson, Theatrum Botanicum the Theater of Plants, 1640, pp. 1516-19; 6 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie fof Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, pp. 1503-6; 7 See Lynday D. Mattison, "Here's Every Type of Cherry and How to Use It", www.tasteofhome.com, gathered 8/2/22; 8 "Cherry", wikipedia.com, gathered 8/3/22; 9 Parkinson, p. 574; 10 Gerard, p. 1503; 11 Louis Lémery, A treastise of foods in general, 1704, p. 12; 12 Parkinson, p. 574; 13 Lémery, p. 12; 14 Parkinson, p. 574; 15 Gerard, p. 1507; 14 Parkinson, p. 574; 16 Gerard, p. 1507; 17 Parkinson, p. 575; 18 Lémery, p. 13; 19 Gerard, p. 1507; 20 Gerard, p. 1506; 21 Lémery, p. 12; 22 Lémery, p. 13

Citron

(Citrus medica)

Called by Sailors: Citron, Pomecitron

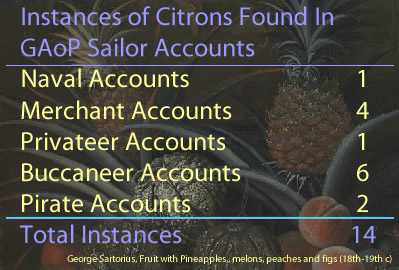

Appears: 14 Times, in 10 Unique Ship Journeys from 8 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Tunis, Tunisia; Tenerife, Canary Islands; Cape Corso Castle, Africa; Santiago, Cape Verde Islands, São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón; Madagascar; Banda Aceh, Indonesia; Kupang, Timor; Barbados; Chepillo Island, Panama; St. Catherine and Salvador, Brazil; St. Catherine, Brazil

Although citrons are included in a variety of sailor's accounts, none of them give any details about them. More than half of these citations are found in the works of William Dampier and more than half of those come from places he stopped during his exploratory journey of Australia in 1699 and 1700

Photo: Johann Werfring - Citron Fruit and Buds on Tree

. Although he is usually takes pains to describe things he came across, Dampier doesn't bother to describe them, however. They have a pirate link, being found in accounts written by sea surgeon John Atkins for the General History of the Pirates, which were included there to add detail the accounts of Edward England's time in Madagascar and Howell Davis' stop at São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón.2 However, no direct connection is made between those crews and citrons. Still, it is very likely that pirates would have used them to make punch.

Physician Hans Sloane says citrons "are frequently to be met with set in Walks, by the Way-Sides, or the Seeds are dropp'd near Plantations, in most Parts of this Island [Jamaica], as well as the Caribes."3 He also mentions that the Portuguese planted them in Brazil where they 'greatly multiply'd'.

Botanist John Gerard describes the fruit itself as "long... often lesser, and not much greater than the Limon [lemon]: the barke or rinde is of a light golden colour, set with divers knobs or bumps, and of a very pleasant smell the pulpe or substance next unto it is thicke, white, having a kinde of aromaticall or spicie smell... the softer pulpe within that, is not so firme or sollid, but more spungie"4.

Botanist John Parkinson includes six different types of fruit in his discussion of 'pomecitrons', although the last three actually appear to be a type of lemon. We will focus on the three which he specifically identifies a citrons. The first - the greater citron - is "great and large fruite, some as great as a Muske Melon, yet others

Citron, From Theatrum botanicum, by John Parkinson (1640)

lesser, but all of them with a rugged bunched out, and uneven yellow barke thicker then in any of the other sorts, and with small store of sowre juyce in the middle, and somewhat great pale whitish or yellow seede". The second, the 'lesser citron', is smaller and longer with a thick yellow rind, containing no juice and fewer seeds than the greater citron. (This sounds similar in many ways to what Gerard described.) The third citron, called the 'bigge-belleyed or double' citron, is like the lesser citron, but paler in color, and "Having another smaller fruite growing within it lying at the very top or head, yet not to be seene before you cut it"5.

Parkinson describes the rind as "sweete in smell, very aromaticall and bitter in taste"6. Gerard says the white inner pulp is "almost without any taste at all" and the juice is sour.7 Parkinson calls the white inner pulp "almost unsavoury and without taste"8.

Parkinson is the only one to comment on how citrons were eaten. He notes that the rind can be preserved in sugar and used in electuaries (pastes). He adds that the inner white pulp "being preserved [in sugar] serveth to sort with other Suckets [candied sweetmeats] at banquets"9.

Gerard says the citron's humoral properties vary; the rind and seed are hot and dry, the white inner pulp is cold, and the inner substance ('pap') is cold and dry.10 His description agrees with that of Parkinson. 'Gross' foods were thought to be converted into undesirable humors in the body. Bodily humors could be either beneficial or detrimental to the body, depending on their qualities and interaction with the humoral makeup of the person.

Gerard goes on to warn that the citron's pulp is "very hardly [difficultly] concocted [converted for use by the stomach], and ingendreth a grosse, cold, and phlegmaticke juyce". Phlegm is one of the four bodily humors. Gerard adds that mixing citron juice with sugar not only improves the taste, but "easie to be digested, more nourishing, and Iesse apt to obstruction and binding or stopping."11

Medicinally, physician John Pechey says, "Every part of the Citron, the outward and inward Bark, the Juice, and Pulp, and the Seeds, are of great use in Physick [medicine].

Photo: Leslie Seaton - Whole and Sliced Citron

"12 Parkinson agrees saying every part of the fruit is "of excellent use"13.

Parkinson dissects nearly every part of the fruit for use in medicine. The rind he credits with helping "to loosen the body". The juice is "singular good in all pestilentiall and burning feavers, to restraine the venome and infection, to suppresse the violence of choller [yellow bile, a bodily humor], and hot distemper of the blood [another humor], and extinguish thirst... stirreth up an appetite, and refresheth the overspent and fainting spirits; resisteth drunkennesse, and helpeth the turnings of the Braine by the hot vapours arising thereinto, and causing a frensie or want of sleep"14.

The

seedes are very effectuall to preserve the heart and vitall spirits, from the poyson of the Scorpion or other venemous creatures, as also against the infection of the plague,or poxes [venereal diseases], or any other contagious disease, they kill the wormes in the stomacke... and [they] hath a digesting quality [are able break something down] and a drying, fit to dry up and consume moist humours, both inwardly in the body, and outwardly in any most or running ulcers and sores15

The citron was powerful stuff, according to Parkinson. He ends by stating that even the branches and the fruit are useful by themselves, being "laid in presses, Chests, or Wardrobes, [they] keepeth cloth,or silke Garments from Moths and Worms, and give them a good s[c]ent also."16

Pechey notes that drying the 'bark' [rind] makes it Cordial (good for the heart) and Alexipharmic (able to cure poisoning.) "It discusses [disperses] Wind powerfully, concocting [combining] and digesting [breaking down] crude Humours that are contain'd in the Stomach or Bowels [thus making them useful to the body]. Being chewed in the Mouth, it cures a Stinking Breath, promotes Concoction of the Meat [food], and is good for Melancholy."17 (Melancholy was believed to be caused by an excess of the humor black bile.)

1 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 217; John Covel, Diary, Early Voyages in the Levant, Thomas Dallam, ed., 1893, p. 120; William Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 124; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 10, 33 & 66; William Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 56 & 72; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 22; Daniel Defoe [Captain Charles Johnson], A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 130; Raveneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 330; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726 p. 54; Nathaniel Uring, The Voyages and Travels of Captain Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 106; 2 Atkins writing in Defoe [Johnson], pp. 130 & 179; 3 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, 1707, p. 177; 4 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie fof Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1462; 5 John Parkinson, Theatrum Botanicum the Theater of Plants, 1640, p. 1505; 6 Parkinson, p. 1506; 7 Gerard, p. 1462; 8,9 Parkinson, p. 1506; 10,11 Gerard, p. 1462; 11 Parkinson, p. 1506; 12 John Pechey, The Compleat Herbal, 1707, p. 241-2; 13,14,15 Parkinson,p. 1506; 16 Parkinson, Theatrum..., p. 1506-7; 17 Pechey, p. 242