Fruit in Sailor's Accounts Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Next>>

Fruit in Sailors Accounts During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 4

Fruit Found In More Than One Sailor's Account, Continued

Lychee

(Litchi chinensis)

Called by Sailors: Letch, Lichea

Appear: 2 Times, in 2 Unique Ship Journeys from 2 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Trenggannu, Malaysia & Haiphong, Vietnam

Lychees only appear in two sailors accounts, suggesting it was either not popular with sailors in the East Indies or was not widely found. Alexander Hamilton only includes them in a list calling them 'letchs'. The Malaysian word for lychee is 'laici', somewhat similar in sound to Hamilton's spelling. The spelling differences could indicated he was not talking about a lychee, but since they grow in Malaysia and the sound is more similar to lychee than to any other fruit, it is likely what he meant. Hamilton prefaces his description with "The Hills [in 'Trangaro'] are low, and covered with evergreen Trees, that Accommodate the Inhabitants with Variety of delicious Fruits"2. Lychees are the fruit of an evergreen tree.

As is his custom, Dampier gives a fairly accurate description of the fruit he found in Tonquin (Vietnam) in 1688. "The Lichea is another delicate fruit. Tis as big as a small Pear, somewhat long shaped, of a reddish colour, the rind pretty thick and rough, the inside white, inclosing a large black kernel, in shape like a Bean.”3

Dampier does not mention the flavor of the fruit. A century before Dampier, Spanish author Juan Gonzales de Mendoza wrote that

Photo: Ivar Leidus - Lychee Fruit and Seed

China grew "lechias ...[which] are of an exceeding gallant tast[e], and never hurteth any body, although [even though] they shoulde eate a great number of them. It [the tree] yeldeth great aboundance of great melons, and of an excellent savour and tast, and [are] verie bigge."4 Polish missionary, explorer and scientist Michal Piotr Boym wrote in 1656 that the 'Li-Ci' "tastes like grapes."5 Publishing well after the golden age of piracy in 1782, French explorer and naturalist Pierre Sonnerat's Voyage aux Indes orientales et à la Chine referred to the fruit as 'Litchi Chinensis'. He notes that it "is very sweet, & one of the best in this country". He elsewhere explains that it "is a good pulp to eat"6. (Note how different these phonetic spellings are from each other, yet similar to Hamilton's 'letch'.)

Little is said of the humoral or medicinal properties of this fruit, probably because most European authors were not familiar with it. Boym does suggest that the Chinese made this and the longan (lum-yen) fruit the core of their medicine, taking it in powdered form.

1 William Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 23 & Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 439; 2 Hamilton, p. 439; 3 Dampier, p. 23; 4 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 914; 5 Juan Gonzales de Mendoza, The history of the great and mighty kingdom of China and the situation thereof, 1853, p. 14; 6 Michal Piotr Boym, Flora Sinesis, 1656, interpreted by the author, not paginated

Mamey Sapote

(Pouteria sapota)

Called by Sailors: Mammee sapote, Mammees supporters

Appear: 2 Times, in 2 Unique Ship Journeys from 2 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Rattan, Honduras; Chepillo Island, Panama

Mamey sapote are trees native to Mexico and Central America which were later cultivated in the Caribbean islands. They are mentioned in the sailor's accounts of William Dampier, who found them on an Chepillo Island near Panama, and Philip Ashton, who was stranded on Rattan [Roatan] island off Honduras after escaping from Edward Low's pirates in 1721.

Ashton's experience of them is interesting in and of itself. He was a Massachusetts fisherman captured off the coast of Nova Scotia by Low in 1722. Upon escaping to Roatan, he found himself without tools or ready knowledge of the area and had to determine what was edible on his own in the beginning of his exile. As Ashton explains, he found

Photo: Meutia Chaerani & Indradi Soemardjan - Mamey Sapote

a sort of Fruit growing upon Trees somewhat larger than an Orange, of an oval Shape, of a brownish Colour without and red within, having two or three Stones about as large as a Walnut in the midst: Tho' I saw many of these fallen under the Trees, yet I dared not to meddle with them for some time, till I saw some Wild Hogs eat them with Safety, and then I thought I might venture upon them too, after such Tasters ...they are called Mammees Supporters, as I learned afterwards.2

Two buccaneer accounts describe this fruit, although one of them is based on buccaneer surgeon Lionel Wafer's months spent healing from a burn among the Kuna natives of inland Panama in 1680 and so is not counted among the sailor's accounts. Both are quick to point out that the mamey sapotes are different from mammee apples (which they often call 'mammees').

Father Jean Baptiste Labat also describes mamey sapotes in the first volume of his Nouveau Voyage aux Isles de l'Amerique. (These are not counted in the above numbers either.) He notes that the French refer to them as apricots, adding that this is only because of their coloring because nothing else about them fits the name. So this fruit is actually found in four sailor's books, although two of them have not been included in the counts above..

Dampier provides a simple description: "The Rind of the Fruit is thin and brittle, the inside is a deep red, and it has a rough flat long Stone."3 Wafer is similarly brief, stating mamey sapotes are small, firm and "of a fine beautiful Colour when ripe."4 Father Labat is more expansive. "Its fruit is almost round, sometimes of the shape of a heart, the point of which is blunt, it is from three inches to seven inches in diameter, it is covered with a grayish bark the thickness of a shield, & even more, strong & binding like leather."5

Labat also explains how the fruit is prepared to be eaten. "After one or two incisions have been made in this rind the

Photo: Daniel Di Palma - Mamey Sapote Growing on Tree

full height of the fruit, it is lifted as if skinning the fruit; one finds under this bark a rather strong yellowish film, although thin, and adhering to the flesh; after it has been removed, the flesh of the fruit is found, which is yellow, firm like that of a pumpkin, and has an aromatic odor which is pleasing."6

Regarding the flavor, Ashton "found them to be a very delicious sort of Fruit"7. Wafer agrees, explaining that it "is very pleasant to the Tast."8 Labat says, "When eaten raw, it leaves a very good taste in the mouth, although a little bitter and gummy." He goes on to explain how the raw fruit can be prepared to alleviate this. "The usual way to eat it is to cut it into fairly thin slices which are put for an hour in a dish with wine and sugar which takes away its bitterness"9. While in Jamaica, physician Hans Sloane noted that some people find the fruit "very pleasant, eat[en] either alone, or because 'tis lusciously sweet and somewhat insipid [lacking in flavor], with Lemon juice mix'd with it"10. He later says that between the sweet flavor and the orange color of the flesh, some people suggest that the fruit produces a natural Marmalade.

Similar to the lychee and the mammee apple, little is said about the medicinal or humoral properties of this fruit in the English medical books used here. Sloane dismissively mentions that some people think it is 'venereal', meaning it has an aphrodisiacal quality. French father Labat reports that the fruit "is excellent for the chest, very wholesome & very nutritious; one finds in its middle one, two, and often three stones as big as pigeons' eggs, and even more depending on the size of the fruit, they are flat on one side, rough and very hard, they contain a white almond and quite bitter which is claimed to be good for binding [the bowels]."11

1 Philip Ashton, Ashton's Memorial, 1726, p. 46-7 & William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 202; 2 Ashton, p. 46-7; 3 Dampier, 1699, p. 203; 4 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of Panama, 1903, p. 98; 5,6 Jean Baptiste Labat, Nouveau Voyage aux Isles de l'Amerique, Tome 1, translated by the author, 1724, p. 342; 7 Ashton, p. 47; 8 Wafer, p. 98; 9 Labat, p. 342; 10 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, p. 125

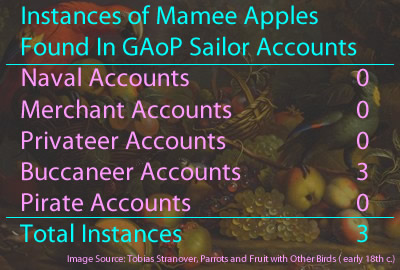

Mammee Apple

(Mammea americana)

Called by Sailors: Mammees, Mammes

Appear: 3 Times, in 2 Unique Ship Journeys from 2 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Jamaica; Tabago; Chepillo Island

This fruit is only mentioned in buccaneer accounts during this time period. Bartholomew Sharp found yellow mammee apples at Tabago in 1680, as did Dampier in 1685.2 Dampier mentions seeing them in both Jamaica and Chepillo Island, Panama in the same year.

Everyone describes something they found unusual or interesting about this fruit. Dampier says of mammee apples,

Artist: Jean-Théodore Descourtilz

Mammee Apple, From Flore pittoresque et médicale

des Antilles (1821)

The Fruit is bigger than Quince, it is round, and covered with a thick Rind, of a grey colour: When the Fruit is ripe the Rind is yellow and tough; and it will then peel off like Leather, but before it is ripe it is brittle: the juice is then white and clammy; but when ripe not so. The ripe Fruit under the Rind is yellow as a Carret, and in the middle are two large rough stones, flat, and each of them much bigger than an Almond.3

Physician Hans Sloane found the Mammee Apple tree on Jamaica. His describes the fruit standing "on a short, thick Footstalk, ...as big as one's Fist, round, or some times having a Ledge, or Crest, the outward Skin being when ripe, yellowish green, rugous [wrinkled], something like a russeting Apple, and having several Filaments on the outward Surface, like some Melons"4.

Dampier doesn't have a lot to say about the flavor of the fruit, only noting that it "smells very well, and the taste is answerable to the smell."5 Sloane is similarly terse. explaining that when mammee apples are ripe, they are "very grateful to the Palate... having something of an Aromatic Taste". He does later add, "It is one of the most pleasant and grateful Fruits to be met with in these Parts"6.

With regard to how mammee apples were eaten, Sloane says it is "by Way of Disert [dessert], as other Fruits."7 Citing Cristobal Acosta as a source, he says they make a good marmalade.8 Seventeenth century plant specialist Nehemiah Grew similarly suggests the fruit makes good conserves, possibly relying on Acosta's text.9

Although several period authors mention the mammee tree and its fruit, little is said about its medicinal properties. Even physician Sloane, who profiles this plant, gives no information on this front. Vaguely related to health, buccaneer surgeon Lionel Wafer says the fruit is 'very wholesome and delicious'.10 (Note that because Wafer's book focuses on time he spent inland in Panama with the Kuna tribe while healing from a burnt leg rather than on what he encountered while sailing, this instance is not counted among the Sailor's accounts.)

1 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 188, 202 & 204; Bartholomew Sharp, "Captain Sharp's Journal of His Expedition", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 33; 2 Dampier, 1699, p. 188 & Sharp, p. 33; 3 Dampier, 1699, p. 188; 4 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, p. 123; 5 Dampier, 1699, p. 188; 6,7 Sloane, p. 123; 8 Sloane, p. 124; 9 Nehemiah Grew, Musaeum Regalis Societatis, 1681, p. 190; 10 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of Panama, 1903, p. 98

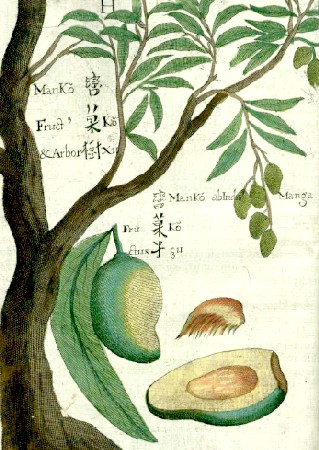

Mango

(Mangifera indica & others)

Called by Sailors: Mango, Mangoe

Appears: 17 Times, in 12 Unique Ship Journeys from 7 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Mocha, Yemen; Goa & Surat, India; Malacca & Trenggannu, Malaysia; Bengkulu, Sumatra; Tanjung Lyar, Java; Borneo; Banda Aceh & Siumpu Island, Indonesia; Pante Macassar, Timor; Aboyna Cay, Haiphong & Côn Sơn Island, Vietnam; Guam; Salvador, Brazil

Nearly all the mangoes in sea accounts appear during the golden age or piracy were found in the East Indies. Modern authors indicate that there are two distinct types of mango found there: those cultivated in the Indian subcontinent (where the mango is believed to have been bred for over 4000 years) and those cultivated in Southeast Asia.2 William Dampier talks about finding them at Pulo Condore [Nam Ha], Vietnam in 1687.

Photo: Asit K Ghosh - Mango Langara, An Indian Cultivar

The Mangoes were ripe when we were there, (as were also the rest of these Fruits) and ...we could smell them out in the thick Woods if we had but the Wind of them, while we were a good way from them, and could not see them, and we generally found them out this way. Mangoes are common in many Places of the East-Indies; but I did never know any grow wild only at this Place.3

It is interesting that a fruit with millennia of cultivation had reached the point where it was no longer found as a wild fruit by Dampier who travelled in much of the area where they were native.

There is one account outside of their indigenous area; William Dampier reported finding them in Salvador, Brazil, which he visited in March of 1699 in the Roebuck. Researchers suggest that they were brought to Brazil for cultivation in the new world around this time4, likely because his was the earliest instance of them being there. As Dampier explains, "Mango's are yet but rare here [Brazil]: I saw none of them but in the Jesuit's Garden, which has a great many fine Fruits... These... were first brought from the East-Indies, and they thrive here very well."5 This may also explain why they do not appear in most 18th century sailor's accounts from the West Indies.

Describing the mangoes he found in Vietnam, Dampier says, "The Fruit of these is as big as a small Peach, but long and smaller towards the Top: It is of a yellowish Colour when ripe; it is very juicy, and of a pleasant Smell... though not so big as those I have seen at Achin and at Maderas or

Photo: Ivar Leidus - Brazilian Mango, Single and Halved

Fort St. George, are yet every whit as pleasant as the best sort of their Garden Mangoes."6

The scent of the mango seems to have been considered important part of describing them, because several authors do so. When William Funnell's ship St. George visited the island of Aboyna off what is now Vietnam in 1705, he said, "The out-side, altho’ ripe, looks green; and within, it is very yellow. It is a very delicious Fruit, when ripe; it has a fine fragrant smell."7

Sailor Alexander Hamilton had a much lower opinion of the Asian mango he found in Malaysia, which he explained is "called by the Dutch a Stinker, which is very offensive both to the Smell and Taste, and consequently of little Use."8 This would seem to be a different type than those Dampier and Funnel praised.

Regarding the flavor of the Indian mango, which sailor Alexander Hamilton found in Goa, India, he says it "is reckoned the largest and most delicious to the Taste of any in the World, and, I may add, the wholsomest and best tasted of any Fruit in the World."10 Dampier approvingly states that the wild mangoes of Vietnam had a "delicate Taste."11

Dampier also provides a local recipe which uses mangoes: "When the Mango is young they [the locals] cut them in two pieces, and pickle them with Salt and Vinegar, in which they put some Cloves of

Artist: Michal Piotr Boym - Mango, From Flora Sinesis (1656)

Garlick. This is an excellent Sauce, and much esteemed; it is called Mango-Achar. Achar I presume signifies Sauce."12 Funnell talks about a similar procedure used in Aboyna. "When they are green, they cut them in two pieces, which they pickle and send to most parts of the World."13

The period English botanical and medical authors used here don't have anything to say about the medicinal properties of Mangoes, suggesting an unfamiliarity with them even though the English had been travelling to the East Indies throughout much of the seventeenth century.

Writing in the early 17th century, Spanish physician and botanist Nicholas Monardes says humorally, mangoes are cold and moist.14 However, German botanist Georg Eberhard Rumphius says mangos are "by nature moist and hot, and generate a thin, rich and bilious [producing the humor bile] food." He later notes that another author, "the learned Paladanus [writing a commentary] in Linschooten either did not know Mangas, or tasted only unripe ones, because he writes that they have a cold nature, something that is only true of the unripe ones, for those are sour and astringent."15

Medicinally, Monardes finds that the "roasted seeds [of mangoes] stop the flux of the body, which I have found to be true, and the marrow, which is inside the seed while it is fresh, kills the worms of the body."16 Polish missionary and scientist Michel Boym also says that mangoes kill worms in the stomach as well as providing "an immediate remedy against diarrhea"17, although it is likely he was drawing on Monardes' work. Continuing in a humoral vein, Rumphius says that mangos "heat the blood somewhat, and therefore generate some fiery skin eruptions called Sudamina in Latin, or more commonly prickly heat"18.

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 480-1; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V2, 1712, p. 65; William Ambrose Cowley, "Cowley's Voyage Round the World", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 25; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 303 & 391-2; Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 23, 124, 163 & 181; Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 66; Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 40 & 72; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 268; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 217-8, 381 & 439; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 178; 2 Emily J. Warschefsky & Eric J. B. von Wettberg, "Population genomic analysis of mango (Mangifera indica) suggests a complex history of domestication", New Phytologisst, Feb., 2007, gathered from the internet 3/24/22; 3 Dampier, 1699, p. 391-2; 4 Warschefsky & von Wettberg, gathered 3/24/22; 5 Dampier, 1699, p. 391-2; 6 Dampier, 1699, p. 391-2; 7 Funnell, p. 268; 8 Hamilton, p. 381; 9 Dampier, 1699, p. 392; 10 Hamilton, p. 217-8; 11 Dampier, 1699, p. 391; 12 Dampier, 1699, p. 391; 13 Funnell, p. 268; 14 Nicolas Monardes, Dell Historia De I Semplici Armoati et altre cose che vengono portate dali Indie Orientali, 1616, translated by the author, p. 221; 15 Georgius Everhardus Rumphius, The Ambonese Herbal, E. M. Beekman, Ed, Vol1, 2011, p. 328; 16 Monardes, p. 221; 17 Michal Piotr Boym, Flora Sinesis, 1656, interpreted by the author, not paginated; 18 Rumphius, p. 328

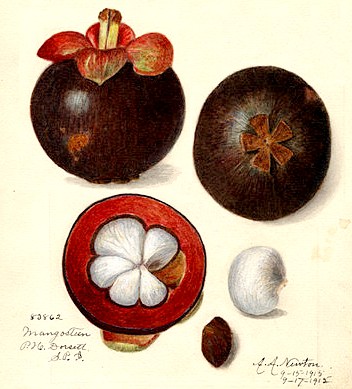

Mangosteen

(Garcinia mangostana)

Called by Sailors: Mangastans, Mangostane, Mangosteine

Appears: 6 Times, in 6 Unique Ship Journeys from 4 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Bengkulu, Sumatra; Banda Aceh, Jakarta & Java, Indonesia; Malacca & Trenggannu, Malaysia

Mangosteens are found only in the accounts of sailor who travelled in the East Indies. It was eventually brought to tropical zones in the West Indies, but not until long after the end of the golden age of piracy.2

Privateer William Funnell was at Batavia (modern Jakarta, Indonesia) aboard the privateer St. George in 1705, where he described the mangosteens: it is "quite round, and looks like a small Pomegranate.

Artist: Amanda Almira Newton - Mangosteen (1915)

The outside Rind is like that of a Pomegranate, only of a darker colour; But the inside of the Rind is of a fine red. Within this Rind is the Fruit, which is of a fine white, and lies in Cloves almost like Garlick. There are commonly four or five of these Cloves in each"3. Dampier likewise indicated they were like small pomegranates when he came across them in Achen (Banda Aceh, Indonesia) while travelling on the East Indiaman Curtane in 1689. He added that the mangosteens rind was thicker, softer, more brittle and darker red than a pomegranate. He explained that the 'cloves' were "about the bigness of the top of a man's thumb. These will easily separate each from the other they are as white as Milk, very soft and juicy, inclosing a small black Stone or Kernel."4Funnell says the white 'cloves' inside the fruit "are very soft and juicy."5

Captain Alexander Hamilton says that "The Kernals [of a mangosteen] are ... of a very agreeable Taste"6. Both Dampier and Funnel agree that the fruit is "very delicious"7. Dampier also states that it is one of the most delicate fruits. Botanist Georg Everhard Rumphius says "they taste, when they are only half ripe, somewhat sour, but the ripe ones are as pleasantly sweet as the best lansas [lanzones] or the ripest of grapes; and very juicy; wherefore many cannot get their fill of this fruit"8.

Hamilton explains, "We commonly suck the Fruit from the Stone... the Stone we throw away, being very bitter if chewed."9 Rumphius likewise

Photo: Wiki User NusHub- Seashore Mangosteen on Tree

notes that the fruits "are eaten raw ...When opening them, one should take care not to get the bark's sap on the flesh, because that will make it bitter; those that are ripe can be pressed with one's hands until they burst open, whereafter one should remove the aforementioned bark or shell very carefully and throw it away"10.

Sailor Hamilton is the only one to make a comment that might indicate the humoral properties of the fruit, warning that it is 'very cold'.11 This is included in his description of the fruit. His comments on medicinal properties are often very general, so it is possible that this may not have anything to do with the quality of the fruit's humors.

From a health perspective, Dampier provides some insight into the way sailors used them. "The outside rind is said to be binding [stops looseness in the bowels], and therefore many when they eat the Fruit... do save the rind or shell, drying it and preserving it, to give to such as have Fluxes."12 Hamilton likewise says the skin, "being dried ...is a good Astringent [stops bleeding]."13 German botanist George Everhard Rumphius agrees with them but doesn't have anything to say about the medicinal value of the fruit, but he does say "the peels are dried and used as a medicine for dysentery and tenesmus [the desire to go to stool despite having nothing to pass]"14.

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 211; William Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 124 & 181; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 286; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 381 & 438-9; 2 Julia F. Morton, Fruits of warm climates. 1987, p. 301; 3 Funnell, p. 286; 4 Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement..., p. 125; 5 Funnell, p. 286; 6 Hamilton, p. 381 & Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement..., p. 125; 7 Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement..., p. 125; 8 Georgius Everhardus Rumphius, The Ambonese Herbal, E. M. Beekman, Ed, Vol1, 2011, p. 389; 9 Hamilton, p. 381; 10 Rumphius, p. 391; 11 Hamilton, p. 381; 12 Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement..., p. 125; 13 Hamilton, p. 381; 14 Rumphius, p. 391;

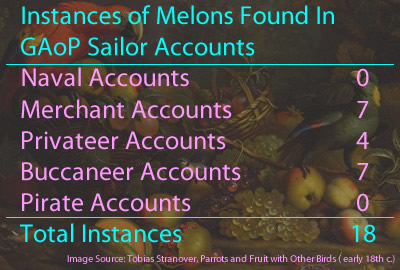

Melon/Muskmelon

(Cucumis Melo)

Called by Sailors: Melon, Millons, Mush-melon, Muskmelon, Pepino, Pepo

Appears: 18 Times, in 12 Unique Ship Journeys from 9 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Goa, India; Haiphong, Vietnam; Ilha Grande & St. Catherine, Brazil and Cape Corse Castle, Africa; Marseilles, France; Santiago & Sao Vincente, Cape Verde Islands; Banda Aceh, Indonesia; Mindanao, Philippines; Kupang, Timor; Guam; Barbados; Salvador, Brazil; Chepillo Island, Panama

Although the word 'melon' sounds less specific than muskmelon, they are actually considered the same thing. Herbalist John Gerard's early seventeenth century Herball includes an entry for the 'Muske-melon, or Million [

Types of Muskmelons Found in India, From IndiaGardening.com

melon]". He explains, "There be divers sorts of Melons found at this day, differing very notably in shape and in proportion, as also, in taste, according to the climate and country where they grow". He says that muskmelons/melons are all "a kinde of Cucumber according to the best approved authors"2. Yet he has a separate entry for cucumbers in his book. Other books on plants from the period explain melons in a similar manner.3

From a modern scientific perspective, melons and cucumbers are closely related, both being a part of the same plant family and genus (cucurbitaceae cucumis). However, melons and muskmelons are both species melo while cucumbers are species sativus.4 As a result, this entry includes accounts mentioning either melons or muskmelons. Generally, however, the word 'melon' is used in lists of edible fruits by sailors who do not mention muskmelons (with one exception.) In all, 7 sailors accounts talk about finding 'melons' during their travels, with 2 other accounts always referring to 'muskmelons'.

William Dampier, From Builders of the British Empire Cards,

Pattreiouex Cigarettes (1929)

This fruit is found 10 times in William Dampier's accounts, with 7 of them calling the fruit 'muskmelon', 2 referring to it as 'melon' and 1 referring to it by both terms. However, the dual instance is a little more complex than it seems. While in Santiago in the Cape Verse Islands in February of 1699, Dampier says they had "melons (both Musk and Water-melons)"5. This indicates muskmelons and watermelons are two different types of a broader category called 'melon'. However, medical and botanical authors from before the golden age of piracy explain that the terms muskmelon and melon are interchangeable, so Dampier is technically incorrect. In addition, although watermelons are a part of the plant family Cucurbitaceae, they are in a different genus (citrullus). Dampier can be at least partially forgiven for this since both the words watermelon and muskmelon contain the word 'melon.' (It is interesting that in his first book written in 1699, he only talks about melons, while in all his later books (written in 1700, 1703 & 1709) he primarily refers to them as muskmelons.)

None of the sailors provide much in the way of a description of the sort of melons they found, suggesting they were quite familiar to period readers. Dampier notes that the muskmelons in Guam were "larger than ours in England" when the Cygnet stopped there in 1686.5 He doesn't spend much time describing them in his books, likely due to their familiarity to the English audience; he even uses them to describe less familiar fruits like papayas, suggesting how well known melons were to his readers.6

Fortunately, the botanists of the period take the time to describe melons. John Parkinson says that there are "divers sorts of Melons found out at this day, differing much in the goodnesse of taste one

Types of Melons, From The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, by John Gerard, p. 917 (1636)

from another. Gerard agrees, describing four different kinds of melons, picturing three of them in his book. The first he calls a 'Muske melon', explaining that the rind is long and sometimes round, of a "russet greene' - almost a tan color, which is "ribbed and furrowed very deepely, having often chaps or chinks) and a confused roughnesse: the pulp or inner substance which is to be eaten is of a feint yellow colour; the middle part whereof is full of a slimie moisture: amongst which is contained the seed."7 The 'feint yellow' flesh suggests a European canteloupe.8 It is curious that Gerard's chapter title indicates that melons and muskmelons are the same thing, yet he identifies this specific type of melon as a muskmelon. Perhaps Dampier wasn't so far wrong after all.

The second melon Gerard calls a Sugar Melon, which he says is as large and round as a coloquintada, having "a most pleasant taste like sugar"9. There is today a melon referred to as a sugar melon, a nearly round, small, orange canteloupe with an especially sweet flavor. The third melon he says is pear-shaped and about as big as a quince (about 2-4 inches) across. The author is unable to suggest a modern equivalent for this. The fourth he refers to as a Spanish melon which he says is "very long, not crested or furrowed at all, but spotted with very many such

Photo: Wiki User Sangfroid - A European Canteloupe,

marks as are on the backe of the Hearts-tongue leafe. The pulpe or meat is not so pleasing in taste as the other."10 This is probably the Piel de Sapo [toad skin] or Christmas melon, which is native to Spain. It is about as sweet as a honeydew melon.

There is nothing unusual about how such melons were consumed. Parkinson says you "paire away the outer rinde, and cut out the inward pulpe where the seede lyeth, slice the yellow firme inward rinde or substance, & so eate it with salt and pepper (and good store of wine, or else it will hardly digest)"11.

Parkinson's comment alludes to health problems created by eating melon. Consumption (often overconsumption) of some fruits was often blamed for upsetting bodily humors by failing to digest properly and not concocting into good humors, thus causing illness. Gerard identifies melon as 'cold and moist' humorally, going to to state that melons are difficult to digest, "and if it remaine long in the stomack it putrifieth,and is occasion of pestilent fevers."12

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 270 & 312; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, Vol. 1, 1712, p. 302 & 311; Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea..., Vol. 2, 1712, p. 15; Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 23 & 125; Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 33 & 71; Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 56 & 72; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 22; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 217-8; Raveneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 330; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 54; Nathaniel Uring, The Voyages and Travels of Captain Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 106; 2 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 917; 3 See for example, William Hughes, The American physitian, 1672, p. 22 and John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1904, p. 525; 4 'Cucurbitaceae', wikipedia, gathered 5/5/2022; 5 Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement..., p. 33; 6 Dampier, A New Voyage..., 1703, p. 34; 7 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie fof Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1517, p. 916-7; 8 Jules Janick, Harry S. Paris, Marie-Christine Daunay, "The Cucurbits And Nightshades Of Renaissance England: John Gerard And William Shakespeare", Horticulture Reviews, Vol. 40; 9 Gerard, p. 917; 10 Gerard, p. 917-8; 11 Parkinson, p. 525; 12 Gerard, p. 918

Olive

(Olea europaea)

Called by Sailors: Olives

Appears: 2 Times, in 2 Unique Ship Journeys from 2 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Marseilles, France & Basra, Iraq

Olives were very familiar to Europeans, only being mentioned twice in all the accounts under study. (Although Edward Barlow lists them twice in his account of Marseilles when the merchant ship Marigold stopped there in 1675, so it's technically three times.) Note that, like coconuts, olives are drupes or 'stone fruit', similar to cherries and peaches. They are somewhat unusual because their oil comes from the flesh of the fruit, while most other edible oils come from the seeds.2

, Bukhard Mucke.jpg)

Photo: Bukhard Mucke - Olive Tree (Olea Europaea)

Neither of the sailor's accounts which mention olives find it necessary to describe them. Botanist John Gerard does give a rather lyrical description of where olive trees are found. "Olive trees grow in very many places of Italy, France, and Spaine; and also in the Islands adjoyning: they are reported to love the sea coasts".3

Fellow botanist John Parkinson identifies two different types of olive trees: manured (cultivated) and wild. Of the cultivated olive, he says they are "round and somewhat long berries, greene at the first and changing pale afterwards, and then purplish, and lastly, when they are full ripe, deepe blacke, and some white when they are ripe"4. He goes on to say that they very in size and shape. Of the wild olives, Parkinson says they are essentially the same as the cultivated variety, producing fruit "in as great plenty, yet much lesser, and scarse comming at any time to ripenesse even in the naturrall places, but where they doe being ripe, they are small with crooked pointes and blacke"5.

Physician John Pechey explains, "Olives, when they are ripe, are black, and taste acrid, bitter and nauseous"6. Fellow physician Louis Lémery advises that, "care must be taken to gather them before they are ripe, and when they have a harsh bitter taste not to be endured, because their Salts are clogged and swallowed up by the earthy and gross parts. Olives are preserved with Water and Salt, and then they become pleasing to the taste"7. He says that the brine engenders 'a little fermentation' which causes the salts to be freed from the olives, taking away the bitter taste. (By salt, he means one of the three Paracelsian elements, which are similar in concept to the humors.)

Cultivated and Wild Olive Branches, From Theatrum Botanicum the Theater of Plants,

By

John Parkinson (1640)

Both authors are correct in stating that olives must be cured by soaking them in brine. However, Parkinson explains this a little better, presenting the various flavors which may be encountered:

...some [olives] are fitter to eat and yeeld not much oyle, others are not to fit to eate, and are smaller yeelding more store of oyle, some againe are gathered unripe and pickled up in brine, (which are the Ollives we use to eate with meate [food]) others are suffered to grow ripe, and then pickled or dryed and kept all the yeare, to be eaten as every one list: Of those Ollives where of oyle is made, some oyle will be delicate sweete and neate, others more fatty or full and strong, some upon the taste will leave no bittemesse or heate in the mouth, but will taste as sweete as butter, others againe will be more or lesse hot and unpleasant in taste8

From a humoral perspective, Gerard identified unripe olives as dry and binding and ripe olives as hot and moist. He noted that pickled olives were dry and binding as well because they "dry up the overmuch moisture of the stomacke, they remove the loathing of meate [food], stirre up an appetite; but there is no nourishment at all that is to be looked for in them, much lesse good nourishment."9 Speaking of the Paracelsian principles, Lémery notes that olives "contain much Oil, Phlegm, and essential Salt."10

Gerard's views on the humoral properties of olive oil were similarly complex. That which was pressed from unripe olives he said was cold and binding, although as it aged, it became hotter.11 Parkinson says the same thing. Parkinson also

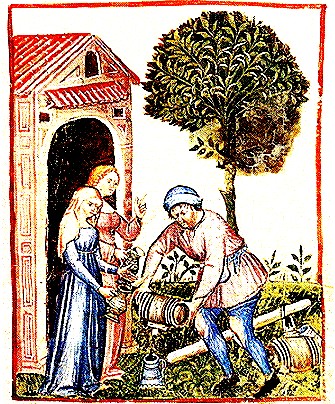

Making Olive Oil, From the Tacuinum of Paris (14th c.)

"Nature: Warm and humid. Optimum: Good month. Usefulness: It fattens

and is easily digestible. Dangers: It weakens the mechanism of digestion."

notes that olive oil made from "fresh or new [olives] is moderately heating and moistening, but if it be old it hath a stronger power to warme and discusse [disperse], which properties are perceived by the sweetenesse, for if the oyle be harsh, it is more cooling then warming"12.

Lémery says "it's of a qualifying [diminishing], mollifying, anodine [relieves pain], dissolving and detersive [cleansing] Nature, good for the Cholick and Bloody-flux"13. Of olive oil, Pechey says, "So

great is use of of the Oil

both for Meat [food] and Medicine, that it would take up too much time to mention all."14 Gerard advises, "The oile of unripe Olives, called Omphacinum oleum, doth stay [stop], represse, and drive away the beginning of tumors and inflammations, cooling the heate of burning ulcers and exulcerations." That pressed from ripe olives, on the other hand, "asswageth paine, dissolveth tumors or swellings, is good for the stiffenesse of the joynts, and against cramps"15.

The botanists and physicians are not the only ones to talk about the healthiness of olives. English naval administrator (and former privateer) Nathaniel Boteler (Butler) also mentions them in his briefing to the head of a Board of Admiralty in 1634.16 Boteler blames sea salt water for causing scurvy, opining that the English Navy should "conform ourselves to the Spanish and Italian nations, who on ship board (and at land, too) live most upon rice, oatmeal, biscuits, figs, olives, oil and the like"17.

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 270 & 272 & Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 78; 2 Alexandra Kicenik Devarenne, "Are Olives a Fruit? Some Fun Facts!", oliveoil.com, gathered 5/9/22; 3 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie fof Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1393; 4 John Parkinson, Theatrum Botanicum the Theater of Plants, 1640, p. 1438; 5 Parkinson, p. 1439; 6 John Pechey, The compleat herbal, 1707, p. 313; 7 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 53; 8 Parkinson, p. 1438; 9 Gerard, p. 1393; 10 Lémery, p. 53; 11 Gerard, p. 1394; 12 Parkinson, p. 1440; 13 Lémery, p. 54; 14 Pechey, p. 313; 15 Gerard, p. 1394; 16 W.G. Perrin, "Boteler's Dialogues", navyrecords.org.uk, gathered 5/9/22; 17 Nathaniel Boteler, Boteler's Dialogues, 1929, p. 65

Orange

(Citrus reticulata &Citrus sinensis)

Called by Sailors: Orange, Orenges, Oringes

Appears: 61 Times, in 43 Unique Ship Journeys from 19 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Almayate & Cape Finisterre, Spain; Livorno & Messina, Italy; Madeira, Portugal; Algiers & Oran, Algeria; Tunis, Tunisia; Santiago & Tenerife, Canary Islands; Santiago & Santo Antao, Cape Verde Islands; Sierra Leone, Africa; Cape Corso Castle, Africa; Ile de la selle, Comoros Islands; Principe; Jamestown, St. Helena; Mauritius; Madagascar; Bombay, Goa, Karwar, Malabar Coast & Thalassery, India; Borneo; Sri Lanka; Banda Aceh, Jakarta, Java & Sumatra Straights, Indonesia; Kupang, Timor; Palau Sabuda, West Papua; Malacca & Trenggannu, Malaysia; Acheen & Bengkulu, Sumatra; Haiphong & Hanoi, Vietnam; Mindanao, Philippines; China; Guam; Barbados; Isla del Carmen, Mexico; Tabago?; Ilha Grande, Salvador & St. Catherine, Brazil; Pisco, Peru; Chepillo Island, Panama

Oranges are the most often mentioned fruit in the period sailor's accounts under study, being found on every type of sailor's account, including William Dampier's exploratory voyage to Australia (counted here as a buccaneer account). Even so, not much is said about their appearance of flavor, although several sailors mention the quality of the flavor of oranges found in different locations.. Oranges were available in the Mediterranean Sea, growing in both Spain and Italy, so Europeans would have been familiar

Artist: Johann Christoph Volkamer

Aranzo da Portugal - Sweet Orange, From Nürnbergische

Hesperides (c. 1710)

enough with the fruit that it wasn't necessary for sailors to describe them in detail.

William Dampier mentions them in every one of his accounts, mentioning finding them in 12 different locations. At the beginning of his exploratory voyage to Australia, Dampier stopped near Salvador, Brazil in March of 1699, an area which he says "produces great variety of fine Fruits, as very good Oranges of 3 or 4 sorts"2. He later adds while there that there were "Several sorts of good Fruits ...especially Oranges, which were in such plenty, that I and all my Company stock'd our selves for our Voyage with them, and they did us a great kindness"3. (What the 'great kindness' the oranges did is not clear, although he next says they also loaded "a good quantity of Rum and Sugar", so the oranges may well have been used as the citrus ingredient for making punch. He could also be referring to their perceived ability to cure scurvy, discussed in detail below.)

French engineer Amedee-Francois Frezier of the merchant ship St. Joseph agreed with Dampier about the quality of Brazil's fruit. He stopped at St. Catherine's Island (Santa Caterina), where he found the oranges to be sweet, noting that "The Fruit-trees there are excellent in their several Kinds: The Orange-trees are at least as good as in China"4.

Edward Barlow seems to have been quite a fan of oranges, mentioning them on 13 different voyages at 18 different locations. He appears to have been pretty interested in their quality, specifically mentioning that he found "very good" oranges in Tenerife, Canary Islands, Java, Indonesia, Goa, India and China5. When the East Indiaman Rainbow stopped in 'Cacho' (Hanoi, Vietnam) in 1688, Barlow said didn't think much of most of the fruit there, but enthused that there were "oranges very excellent good of two or three sorts"6. His highest written praise was for oranges he found in Toulon, France in 1675 on a merchant run to the Mediterranean where there were "excellent fruits of all sorts, as ‘Chena’ oranges of that sort as good as ever I ate"7.

Orange Citrus aurantium, A Barra, China (Sweet) Orange, Citrus Sinensis, Ellen Levy Finch.jpg)

Photos: A Barra (top) & Ellen Levy Finch (bottom)

The Seville (Bitter) Orange - Citrus aurantium (top) and the

China (Sweet) Orange -Citrus sinensis (bottom)

Unlike most fruits discussed in the sailor's books during this time, several sailors differentiate between oranges. The two types most discussed are China and Seville, with the difference being that those called 'China' oranges were sweet, while those called 'Seville' were bitter. It is tempting to think that the sweet oranges were Chinese and the bitter were Spanish based on their names, but this is not the case; both originated in China. Seville oranges were brought to Spain by Arab occupiers during the 10th or 11th century A.D. and were the only type of orange grown there until the mid-fifteenth or sixteenth century when the Portuguese brought sweet oranges to Europe from China.8

China (sweet) oranges are specifically referred to 5 times in the sailors accounts9. One of these accounts, that of Amedee-Francois Taylor, only mentions China oranges indirectly at St. Catherine's Island, Brazil although he had had earlier said that while they were there, the sailors had "loaded our Yawl with sweet Oranges, Lemons, and large Limes."10 Given that the China oranges were generally considered sweet, it is fairly certain that those were the ones they took aboard. Many of Edward Barlow's citations might refer to China oranges given his comment about finding the best China oranges he had ever eaten in Toulon, but this cannot be verified. When Dampier found 3 or 4 types of 'very good' oranges around Salvador, Brazil, he says parenthetically that one sort of China orange was especially good.11

Seville (bitter) oranges are found in 7 accounts12. Physician John Atkins says he found them in Sierra Leone, Africa where the woods contained "many Sevil-Orange Trees, the Fruit largest and best tasted of any I ever met)"13. Although not commenting on their quality, East Indies based ship captain Alexander Hamilton mentioned that the "English East-india Company’s [garden] is the best, and best cultivated. It produces plenty of Seville Oranges, whose Trees are always verdant, and bear ripe and green Fruit, with Blossoms, all at once."14

Dampier talks at some length about two types of oranges he found in Vietnam while visiting there aboard the East Indiaman Curtane in 1688. He stated that they were "more excellent than" other varieties he had tasted. One of these he notes are called Cam chain by the Vietnamese and other Cam quit,

Artist: Johann Christoph Volkamer

Aranzi Nanini da China (Dwarf Oranges of China),

From Nürnbergische Hesperides (c.1710)

advising that "Cam, in the Tonquinese Language signifies an Orange, but what the distinguishing words Cam [sic. He means 'Chain'] and Quit signifie I know not."15 In fact, in Vietnamese, cam does mean orange, although which exact types Dampier is talking about is uncertain.

Today, Chanh by itself means lemon and, when combined with cam is used to refer to citrus. Dampier's description of this states it "is a large Orange, of a yellowish colour: the rind is pretty thick and rough; and the inside is yellow like Amber. It has a most fragrant smell, and the taste is very delicious. This sort of Orange is the best that I did ever taste; I believe there are not better in the world"16. This likely refers to one of the several types of sweet oranges found Vietnam, possibly one that has been crossed with a pomelo, producing the yellow color. Cam (orange) + Chanh (lemon) would seem to be an appropriate description of such a fruit. Based solely on the name, two varieties suggest themselves. Vietnam is somewhat renowned for their cam sành orange has a green or yellowish-green rind. They also produce an orange called cam canh which is yellow on the outside. Both are sweet like Mandarin oranges.

Quýt today means tangerine with Cam Quýt means Mandarin orange. Dampier says that this orange "is a very small round Fruit, not above half so big as the former. It is of a deep red colour, and the rind is very smooth and thin. The inside also is very red; the taste is not inferior to the Cam chain"17. He later adds that these oranges become redder and the peel thinner later in the season. Neither tangerines nor mandarin oranges are red, although both are fairly dark orange. They are smaller, have a thinner skin and are sweeter than regular oranges, so much of Dampier's description fits them. The coloring sounds like a blood orange, although they were developed in Italy, mostly likely after this period in history.. Vietnam also has an orange called cam bo which yellowish-red and could also be the fruit Dampier is discussing here.

Oranges appear in three different pirate accounts and are alluded to in a fourth account (which is not counted here as an instance of pirates getting oranges). As suggested, oranges were one a couple different citrus fruits

Cartographer: Jacques Nicolas Bellin

Carte de l'Isle d'Anjouan - Map of Anjouan, Comoros Islands (1748)

often used to make punch, so the pirates' interest in them shouldn't be entirely surprising. One of the pirate/orange citations come from a description of the fruit available that Madagascar when Edward England's pirates were there.18 Another simply lists oranges as one of the foods that John Gow's pirates took from a French ship captured off the cape at Gallica, Spain.19 The most descriptive of the three pirate/orange accounts also concerns England, involving a stop at 'Annabar' [Annobόn] where they "took in more water and Oranges and about fifty hogs which we paid for part money, part small arms."20 The final, indirect link between pirates and oranges comes from East India captain Alexander Hamilton, who explains that Anjouan in the Comoros Islands had "good Lemons and Oranges, so that most Part of the English Shipping bound to Mocha and Surat, usually called there for Refreshments, till the Pirates began to frequent it."21

From a food standpoint, botanist John Parkinson says "Orenges are used as sawce for many sorts of meates [foods], in respect of their sweete sowernesse [apparently talking about Seville oranges], giving a rellish of delight wheresoever they are used."22 He adds, "The dryed rinde, by reason of the sweete and strong s[c]ent, serveth to bee put among other things to make sweet pouthers [powders]." He further notes that when Seville orange peels are steeped in sugar it removes some of the bitterness, so that they "serve either as Succots, and bandquetting stuffes, or as ornaments... to give rellish unto meats whether baked or boyled"23. Parkinson's comments refer to food prepared on land, because oranges would not keep very long at sea. It is possible sailors may have dried the peel, but, given the talent level of most ship's cooks, it is highly unlikely anything so fancy would part of their menu.

Herbalist John Gerard lumps oranges in with lemons and citrons. He notes that each fruit has humoral properties of differing strengths without going into detail about those of oranges. He says all these fruits have sweet-smelling peels that are "bitter, hot and dry" humorally. He says the 'white pulpe' (the pulp) is cold and the fruit itself is cold and dry, particularly for the lemons and citrons.

The Orange Tree, From the Tacuinum of Rouen (15th c.)

Again, no mention is specifically made of the humoral qualities of the oranges, but presumably he believes them to be less cold and dry than the other fruits because they are sweeter. "The seed because it is bitter is hot and dry."24 The 15th century health treatise Tacuinum Sanitatus of Rouen is a little more definitive, stating that the orange "pulp is cold and humid in the third degree, the skin is dry and warm in the second."25

Dampier mentions the health properties of his two Vietnamese oranges in his account. He advises that the Cam chain "are so innocent, that they are not denied to such as have Fevers, and other sick people"26. However, the Cam-quit "is accounted very unwholesome fruit, especially to such as are subject to fluxes for it both creates and heightens that distemper"27.

Oranges were also generally, if not officially, recognized to be one of the several things that cured scurvy. Writing in the 1630, navy sailor Nathaniel Boteler mentions in his apparent briefing to the Admiralty that "oranges, lemons, limes, pines [pineapples]; ...are excellent against the scorbute"28. Writing in 1639 about curing scurvy, sea surgeon John Woodall explained that "the Chirurgion or his Mate must not faile to perswaide the Governour or Purser in all places where they touch in the Indies and may have it, to provide themselves of juice of Oranges, limes, or lemons, & at Banthame of Tamarinds"29. Fellow sea surgeon John Moyle advised that "where the Succulent Herbs, and Roots, and Fruits as Lemmons and Oranges, are freely taken, and good wine drank; there's no fear of the scurvy, for they attenuate the Blood, and open Obstructions, and prevent that Distemper."30

Medicinally, Parkinson says that orange peels "helpe to warme a cold stomack, and to digest [dissolve] or breake winde therein" and the juice can be drank "to prevent or to helpe any pestilentiall fever."31 Physician John Pechey says the the juice "creates and Appetite and extinguishes Thirst: and therefore is of good use in Fevers. Oranges are excellent for curing the Scurvy."32 He says the seeds "Kill the worms in Children... they taste very pleasantly, and strengthen the Stomach, and create an Appetite."33

1 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 26, 48-9 & 217; John Baltharpe, The straights voyage or St Davids Poem, 1671, p. 64; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 58, 69, 81, 86. 163, 186, 188, 208, 211. 270, 273, 283, 372-3, 375, 395, 402, 431, 467-7 & 518; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, Vol. 1, 1712, p. 26; Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea..., Vol. 2, 1712, p. 15 & 93; John Covel, "Diary", Early Voyages in the Levant, Thomas Dallam, ed., 1893, p. 120; William Ambrose Cowley, "Cowley's Voyage Round the World", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 16 & 25; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 311; Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 23-4, 124, 163 & 181; Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 94 & 107; Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 10 & 66; Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 56, 72 & 98; Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 24 & 162; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 12, 22 & 186; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 5 & 286-7; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 29, 90, 381 & 438-9; Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 130; Raveneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 330; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 158-9 & 191; Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 25-6, 27; Bartholomew Sharp, "Captain Sharp's Journal of His Expedition", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, ed., 1699, p. 33; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 54; Henry Teonge, The Diary of HenryTeonge, 1825, p. 268; Nathaniel Uring, The Voyages and Travels of Captain Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 90-1 & 106; 2 Dampier, A New Voyage..., Vol III, p. 66; 3 Dampier, A New Voyage..., Vol III, p. 68; 4 Frezier, p. 22; 5 Barlow, pp. 272, 283, 402 & 518; 6 Barlow, p. 395; 7 Barlow, p. 270; See Marion Eugene & Audrey H. Ensminger, Foods & Nutrition Encyclopedia, Vol. 2, 1994 pp. 1990-1, Trinidad Botanical Department, Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information, Vol. 3, 1896, p. 111 & Elizabeth Nash, Seville, Córdoba, and Granada: A Cultural History, 2005, p. 14; 9 Barlow, p. 273, Dampier, A New Voyage..., Vol III, p. 67, Frezier, p. 22, Shelvocke, p. 54 & Uring, p. 106; 10 Frezier, p. 21; 11 Dampier, A New Voyage..., Vol III, p. 66; 12 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea, Brazil and the West Indies, 1735, p. 48, Barlow, p. 270, Dampier, A New Voyage..., Vol III, p. 48 & 67, Hamilton, p. 90, Shelvocke, p. 54 & Uring, p. 106; 13 Atkins, p. 48; 14 Hamilton, p. 90; 15, 16, 17 Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement... ,1700, p. 23; 18 Defoe (Johnson), p. 130; 19 “33. James Williams, from The Examination of James Williams, 27 March, 1725. HCA 1/55 ff. 103-104”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 162; 20 “2. William Phillips The Voluntary Confession and Discovery of William Phillips, 8 August, 1696. SP 63/358, ff. 127-132”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 24; 21 Hamilton, p. 29; 22 John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1904, p. 584 23 Parkinson, p. 586; 24 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie fof Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1463; 25 "VIII. Oranges (Cetrona Id Est Narancia)", Tacuinum Santatis, 14th century, not paginated; 26 Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement... ,1700, p. 23; 27 Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement... ,1700, p. 23-4; 28 Nathaniel Boteler, Boteler's Dialogues, 1929, p. 66; 29 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1639, p. 164; 30 John Moyle, Chirurgus marinus, or The sea chirurgion, 1693, p. 181; 31 Parkinson, p. 586; 32 John Pechey, the compleat herbal, 1707, p. 316; 33 Pechey, p. 317

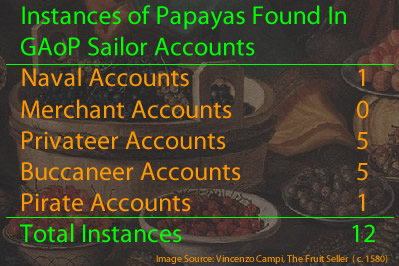

Papaya

(Carica papaya)

Called by Sailors: Papaes, Papais, Papah, Papas

Appears: 12 Times, in 6 Unique Ship Journeys from 6 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Tenerife, Canary Islands; Santiago, Cape Verde Islands; Sierra Leone, Africa, Principe; Mappakasunggu & Siumpu Island, Indonesia; Palau Sabuda, West Papua; Guam; Salvador, Brazil; Coiba, Panama; Atacames, Ecuador;

Papayas appear in quite a number of sailor's accounts from the period. The majority of these instances are found in William Dampier's books (5 times on two different journeys) and Edward Cook's account of Woodes Rogers privateer voyage from 1708-11 (4 times). They do appear in one pirate account, but only because sea surgeon John Atkins wrote a description of the island Principe as background for the section found on Howell Davis in The General History of the Pirates. Whether Davis or his crew actually ate or

Artist: Thomas Prathysh - Papaya Fruit

even saw papayas is anyone's guess. In Dampier's account of the Roebuck's exploratory voyage of Australia, he stopped at Santiago, Cape Verde Islands in February of 1699, mentioning that the fruit was found in all the islands in that chain.2

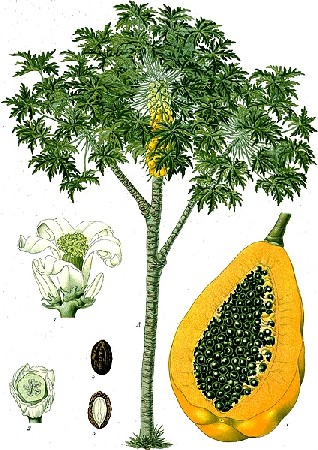

Ever curious, Dampier described papayas as "a Fruit about the bigness of a Musk-Melon, hollow as that is, and much resembling it in Shape and Colour, both outside and inside: Only in the middle, instead of flat Kernels, which the Melons have, these have a handful of small blackish Seeds, about the bigness of Pepper-corns"3. Atkins describes their size in his account of Principe as "a Fruit less than the smallest Pumkins"4 and in his own account of Sierra Leone as "the Size of a moderate Melon"5.

Physician Hans Sloane indicates that papayas range in size. He says that the fruit's "outward Skin is smooth, before it is ripe [it is] very green, when ripe, yellow, and containing within a yellow... Pulp". He adds that the seeds are round with "each Seed being as big as a Pea, black, having several Risings and Impressions on its Surface, and being inclos'd in a whitish clear Bladder."6

Dampier says that the "Taste is also hot on the Tongue somewhat like Pepper. The Fruit it self is sweet, soft and luscious, when ripe;

Artist: Franz Eugen Köhler

Carica papaya, From Köhler's Medizinal-Pflanzen (1897)

but while green 'tis hard and unsavory: tho' even then being boiled and eaten with Salt-pork or Beef, it serves instead of Turnips, and is as much esteemed."7 Sloane says ripe papaya have "sweet Pulp", although he admits that, "in my Opinion it is not a very

pleasant Fruit, even when help'd with Pepper and Sugar."8

Other recipes and suggestions for eating papayas are found in various accounts from the period. Atkins explains that papayas are suitable "for boiling, and to be eat[en] with Meat ...[being] improved by the English into a Turnip or an Apple Taste, with a due Mixture of Butter and Limes."9 Sloane suggests, "The more ordinary Use of this Fruit, is before it is ripe, when as large as one's Fist, it is cut into Slices, soak'd in Water till the milky Juice is out, and then boil'd and eat as Turneps, or bak'd as Apples." He mentions that it is preserved and sent to Europe as "Sweetmeat" or candy. However, he warns that ""when not fully ripe, [the fruit] cut athwart, yields, in several Places a Milky Juice, which is thought very unwholesome if before being dress'd, the Fruit be not steep'd in Water."10

Sloane talks about the medicinal properties of the fruit, although he freely admits that everything he says comes from other authors. From Francisco Ximenez's 1615 books Quatros Libros, he notes that the fruit is "very cooling and Cordial [good for the heart] and used in the Hospitals of New-Spain."11 Sloane says botanist Carolus Clusius claims the fruit "loosens the belly"12. Opposite to this, Samuel Purchas states that those he found in Puerto Rico were "a remedie against the fluxe", which he says one would not think to look at them.13 Charles de Rochefort takes a middling stance, suggesting the fruit strengthens the stomach and helps with digestion.14 Dutch East India Company employee and botanist Georg Eberhard Rumphius says "they do not fill the stomach very well, providing a slimy and corruptible food, wherefore they are mostly eaten for pleasure, or to cool the stomach when it is hot".15

1 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 49; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V1, 1712, p. 15; Cooke, A Voyage..., V2, 1712, p. 41, 43 & 93; William Ambrose Cowley, "Cowley's Voyage Round the World", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 16; William Dampier, "Part I," A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 10, 33-4 & 66; Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 98; John Atkins in Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 185; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 356; 2,3 Dampier, "Part I," A New Voyage..., p. 34; 4 Atkins in Defoe (Johnson), p. 185; 5 Atkins, A Voyage..., p. 49; 6 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, 1707, p. 165; 7 Dampier, "Part I," A New Voyage..., p. 34-5; 8 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, 1707, p. 165; 9 Atkins in Defoe (Johnson), p. 185; 10,11 Sloane, p. 165; 12 Sloane, p. 165; 13 Samuel Purchas, Purchas His Pilgrimes: In Five Bookes, Vol. 4, 1625, p. 1172; 14 de Rochefort, Histoire naturelle et morale des iles Antilles de l'Amerique, 1681, translated by the author, p. 65; 15 Everhardus Rumphius, The Ambonese Herbal, E. M. Beekman, Ed, Vol1, 2011, p. 418

Peach

(Prunus persica)

Called by Sailors: Peach

Appears: 11 Times, in 11 Unique Ship Journeys from 8 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Tenerife, Canary Islands; Cadiz, Spain; Madeira, Portugal; Basra, Iraq; Aden & Mocha, Yemen; Charleston, SC; Coquimbo, Chile;

Peaches were very familiar to English sailors. So much so that Nathaniel Uring specifically refers to them as 'European Fruits'.2 Like some other familiar fruits, the sailors used them to help draw a mental picture of unfamiliar foreign fruit in the minds of their readers.3 Because of this, none of them spend much time describing the fruit, other than to qualify them. When the explorer ship Roebuck stopped at the Canary Islands in 1699, William Dampier said the peaches there were excellent.4

Artist: John Parkinson

Varieties of Peaches, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (1629)

1- Apricot, 2-Melocotón Peach, 3-Nutmeg Peach, 4-Black Peach

5-Long Carnation Peach, 6-Queen's Peach, 7-Almond,

8-Peach

du

Troas, 9-Romaine Red Nectarine, 10- Bastard Red Nectarine

Edward Barlow similarly found "very good Peaches" in the Canaries in 1676 as well as in Mocha, Yemen in 1697.5 Sailor Alexander Hamilton said the peaches grown at Mocha were merely good6, while those found in Basrah, Iraq were delicious.7 The highest praise for peaches comes from Nathaniel Uring's stop at Charlestown, SC in July of 1718 on the Bangor Galley. He enthused, "their Peaches are the best I ever tasted."8 (It's too bad he couldn't have gotten one fresh from Georgia.)

Fortunately, because they were common in Europe, botanists from the period have much to say about peaches. John Gerard lists a variety of types of peach, which he notes differ primarily only in the type of fruit they bear. His list includes "Nutmeg Peaches; The Queenes Peach; The Newington Peach; The grand Carnation Peach; The Carnation Peach; The blacke Peach; The Melocatone; The White; The Romane; The Alberza; The Island Peach; Peach du Troy. These are all good ones."9 John Parkinson gives detailed description of these peaches as well as a few others, but for brevity's sake we will only include his description of the russet peach which he says "is one of the most ordinary Peaches in the Kingdome, being of a russet colour on the outside, and but of a reasonable relish"10 Parkinson provides a nice image of some of the peaches he discusses (seen at right) with his descriptions of them often including things like the size, color and taste of the various types.

English herbalist John Gerard gives a pretty accurate description of a typical peach. "The fruit or Peaches be round, and have as it were a chinke or cleft on the one side; they are covered with a soft and thin downe or hairy cotton, being white without, and of a pleasant taste; in the middle thereof is a rough or rugged stone, wherein is contained a kernell like unto the Almond; the meate about the stone is of a white color."11

Artist: Peter Bohl.- Still Life with Peaches (Between 1650 - 74)

French botanist Louis Lémery describes the best peaches for consumption as those "of an agreeable smell, soft pulp, juicy, vinous, well coloured, full ripe, and that are not easily separated from the stone [pit]."12 English Physician John Pechey notes that a ripe peach has "a sweet and pleasant Smell, and refreshes the Spirits."13

The botanists and physicians didn't provide much detail on how peaches could be eaten or used in recipes. The one mention of peaches being prepared is found in privateer George Shelvocke's account of capturing the Spanish vessel de Conception de Recova somewhere between Sonsonate, El Salvador and Panama in May of 1721. Among the the foods they found on board were "Jars of preserv'd Peaches"14. One cannot but help wonder why preserved fruits weren't staples of sea voyages.

, C. Chabot, 1876.jpg)

Artist: C. Chabot -

Peach plant, Prunus persica (1876)

Humorally, Gerard says peaches are "cold and moist,and that in the second degree... [and] the kernels [pits] of the Peaches be hot and dry"15. Lémery says peaches contain much Phlegm, essential Salt, and very little Oil."16 This refers to the Paracelsian 'active chemical ingredients' which are very similar to the concept of bodily humors.

Medicinally, Gerard says peaches "doth easily putrifie, which yeeldeth no nourishment, bringeth hurt, especially eaten after other meats [foods] for then they cause thee other meats to putrifie. But they are lesse hurt full if they be taken first; for by reason that they are moist and slippery, they easily and quickly descend, and by making the belly slippery, they cause other meats to slip down the sooner."17 Parkinson says something very similar, explaining that because the putrefy so easily, the cause "surfeits often·times; and therefore every one had neede bee carefull, what and in what manner they eate them: yet they are much and often well accepted with all

the Gentry of the Kingdome."18 Lémery concurs with these assessments of a peach's impact on the digestive tract. He explains that since "Peaches are a soft and moist substance, they easily and soon corrupt in the first passages, cause Wind and Worms"19. Curiously, Gerard says unripe peaches "stop the laske [diarrhea], but being ripe they loosen the belly and being applied plaisterwise unto the navel of yong children, they kil the worms, and drive them forth."20 This disagrees with Lémery's comment that they cause worms.

In addition to those assessments of the medicinal qualities of the peach, Lémery adds that they "help a stinking breath.... they cool, moisten, and are a little opening [of obstructions in the organs]."21 Parkinson suggests that peach pits are "given to them that cannot well make water [urinate], or are troubled with the [kidney] stone; for it openeth the stoppings of the urinary passages, whereby much ease ensueth."22

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 283 & 481; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 10; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 52 & 78; Jean-Baptiste Labat, The Memoirs of Pere Labat, 1693-1705, John Eadon ed, 1970, p. 262; Basil Ringrose, The Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp, And Others, in the South Sea, 1684, p. 41; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 174 & 233; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 371; Nathaniel Uring, The Voyages and Travels of Captain Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 229; 4 Dampier, 3 See for example, Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Shonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 187 & Francis Rogers. Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, Bruce S. Ingram, ed., 1936, p. 158; 4 Dampier, p. 10; 5 Barlow, p. 283 & 481; 6 Hamilton, p. 52; 7 Hamilton, p. 78; 8 Uring, p. 229; 9 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie fof Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1446; 10 John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1904, p. 580; 11 Gerard, p. 1446; 12 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 15; 13 John Pechey, the compleat herbal, 1707, p. 182; 14 Shelvocke, p. 371; 15 Gerard, p. 1447; 16 Lémery, p. 16; 17 Gerard, p. 1447; 18 Parkinson, p. 582; 19 Lémery, p. 16; 20 Gerard, p. 1447; 21 Lémery, p. 15; 22 Parkinson, p. 582;