Fruit in Sailor's Accounts Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Next>>

Fruit in Sailors Accounts During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 3

Fruit Found In More Than One Sailor's Account, Continued

Coconut

(Cocos nucifera)

Called by Sailors: Coconut, Cocoanut, Coco-nut, Cocoa-nut, Cocao-nut

Appears: 46 Times, in 25 Unique Ship Journeys from 15 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Santiago, Cape Verde; Cape Corso Castle and Sierra Leone, Africa; St. Mary's Island, Madagascar; Anjouan, Comoros Islands; Belopatan, Bombay, Goa, Karwar, Laccadive Islands, Malabar Coast, Mangaluru and Thalassery, India; Sri Lanka; Bengkulu, Sumatra; Banda Aceh, Buton, Java, Mappakasunggu, Pulau Bintan, Palau Sanding(?), Palau Sinka(?), Panaitan and Sumatra Straights, Indonesia; Kupang & Pante Macassar, Timor, Malacca, Malaysia; Haiphong, Vietnam; Palau Sabuda, West Papaua; Lamoran, New Ireland; Fulleborne, new Britain; Guam; Rattan, Honduras; Tabago (?); Salvador, Brazil; Paita, Peru; Atacames, Ecuador; Salahonda, Columbia; Gulf of Nicoya, Costa Rica

Of all the fruit found in sailor's accounts during this period, none seems to have captured their imagination quite like the coconut. Seven different authors felt the need to discuss coconuts in detail, highlighting their flavor and qualities as food, the uses of both the fruit and the parts of the tree they grew upon and how they were to be prepared, among other things. William Dampier devoted six pages of his first book to describing the coconuts found on Guam, adding a few more sentences on those found on a small island in Indonesia (possibly modern Palau Sinka).2

Coconuts are described in the various sailor's texts as "a

A vertical section of a coconut, From The Encyclopedia of

Food,

by Artemas Ward (1923)

very good fruit", "sweet", "a pleasant mess [meal] enough" and "sweet and pleasant to eat, and very filling."3 Coconut milk is even more highly praised, being referred to as "a cool pleasant liquor they call milk, which is mighty pleasing to drink", "pure clear Water, which is very cool, brisk, pleasant and sweet", a "sweet, delicate, wholsom and refreshing Water" and "sweet and good"4. Such comments refer to both the liquid found in the coconut naturally and that obtained by making coconut milk.

The process of producing coconut milk was interesting enough for several sailors to describe it. While the Buccaneer Revenge was at Guam in 1685, William Ambrose Crowley explained "a French Jesuite ...taught us to make Milk of the Cocoa-Nuts, by scraping of them, and putting Water to them, and then squeezing them; which will cause them to look like Milk, and receive a very pleasant taste."5 Dampier describes the process differently, noting that when making the milk, you start "with a small Iron Rasp made for the purpose, the Kernel or Nut is rasped out clean, which being put into a little fresh Water."6 Privateer William Funnel describes a similar process, adding several interesting details. "The Kernel of the Nut is also very good; which if it be pretty old, we scrape all to pieces; the scrapings we set to soak in about a quart of fresh Water for three or four hours, and then strain the Water; which when strain'd hath both the colour and taste of Milk: And if it stand a while, it will have a thick scum on it, not unlike Cream."7

Dampier also notes some variations in the manner of consuming coconuts. He said that some of the natives of Guam eat them while they are "young and soft like Pap... scraping it out with a Spoon, after they have drunk the Water that was within it. I like the Water best when the Nut is almost ripe, for it is then sweetest and briskest."8 He says that even though some coconut trees grown in places where the salt water washes over the land on islands near Sumatra, "the Kernel is thick and sweet; and the Milk or Water in the inside, is more pleasant and sweet than of the Nuts that grow in rich ground, which are commonly large indeed, but not very sweet. These at Guam grow in dry ground, are of a middle size, and I think the sweetest that I did ever taste."9

Coconut oil was also extracted from the coconut milk-making

Processing Coconut Oil in the Philippines

process. Dampier suggested it was "the greatest use of the Kernel... [used for] both for burning and for frying." He explains, "The way to make the Oyl is to grate or rasp the Kernel,and steep it in frew [fresh] Water; then boil it, and scum off the Oyl at top as it rises: But the Nuts that make the Oyl ought to be a long time gathered, so as that the Kernel may be turning soft and oily."10

Writing for the General History of the Pirates, Surgeon John Atkins said that coconuts produced a "pleasant scented Oyl, used as Food and Sauce all over the Coast, but chiefly in the Windward Parts of Africa, where they stamp, boil and skim it off in great Quantities"11. Privateer Funnell provides a different take, explaining that when a coconut "be very old, the Kernel will of it self turn to Oyl, which is often made use of to fry with, but most commonly to burn in Lamps."12 Missionary Domingo Navarette said that in 1657, the people who lived in Makasar, Indonesia "are always employ'd in making Oil of Coconuts, of which they sell very much, and pay a great deal of Tribute to the King of Macasar. Whilst we were there, he sent to demand of them 90,000 Pecks of Oil."13

A vertical section of a coconut, From The Encyclopedia of

Food,

by Artemas Ward (1923)

In addition to the coconut providing food, other parts of the fruit and the coconut tree were used. While in India aboard the Indiaman Experiment in 1670, Edward Barlow said the coconut was "the 'necessariest' fruit that grow, they making things for all uses, being both meat and drink, and clothing and cables and rigging for this country's vessels." He was so impressed with them he brought some home "to show some that were desirous to see the fashion of them"14. Atkins says that West African palms trees "may be reckoned the first [most important] of their natural Curiosities, in that they afford them Meat, Drink and Cloathing"15. Sailor Francis Rogers likewise mentions that the coconut "tree affords meat, drink, lodging, and cordage" to the inhabitants of the Comoros Islands, north of Madagascar.16

Dampier apologizes for devoting so much time to the coconut in his text, explaining that it "is possibly of all others [plants] the most generally serviceable to the conveniences, as well as the necessities of humane Life."17 Dampier goes on: "Yet this Tree, that is of such great use, and esteemed so much in the East-Indies, is scarce regarded in the West-Indies, for want of the knowledge of the benefits it may produce."17

However, the usefulness of coconuts was not completely ignored in the West Indies. Privateer William Funnel of the St. George says

Artist: Camille Pissarro - Coconut Trees "au bord de la mer}, St. Thomas (1856)

that in 1704 the natives of Salhonda Bay, Columbia produced "Meat, Drink, Clothing, houses, Firing and Rigging for their Ships" from the coconut tree.18 He elsewhere mentions that the shore by the Motine mountains of Ecuador, "is all along planted with Cocoa-nut Trees, for the use of those Ships which come hereabouts"19. When George Shelvocke's privateering ship Speedwell took Paita, Peru, they took "what plunder we had got, which consisted in hogs, fowls, brown and white Calavances [hycianth bean], beans, Indian corn, wheat, flour, sugar, and as much cocoa-nut as we were able to stow away, with pans, and other conveniences for preparing it".20

There are a few non-food uses of coconuts discussed in any detail. The first is as roof thatching. William Funnell says, "The Leaves of the Tree, serve to thatch Houses"21. Francis Rogers concurs, explaining that in the Comoros Islands, the natives use "the leaves of this tree they cover their houses, which they call Cajan leaves."22 Father Navarette says that for the Indonesians, "the Trunk of the Tree and Branches... serve for many other uses."23 Unfortunately, he doesn't expand upon this.

The most useful non-food-related part of the coconut was the green husk that covers the nut. Francis Rogers says that using

Photo: Radwa Radwan - Egyptian Palm Leaf Weaver Making Rope

"the green shell, which is tough and stringy, and of which, with the bark of the tree, they make ropes (which they call Bass [bast - fibrous plant material] ropes) for their vessels, etc."24 Funnell expands upon this noting that the husk could be used to "make Ropes for Ships, as Rigging, Cables, &c. which are a good Commodity in most places of the East-Indies."25 Dampier gives more insight as to how this is done. "[T]he dry husk is full of small Strings and Threads, which being beaten, becomes soft, and the Other Substance which was mixt among it falls away like Saw-dust, leaving only the Strings. These are afterwards spun into long Yarns, and twisted up into Basts for Convenience; and many of these Rope-Yarns joined together make good Cables."26 In the Maldives, coconut husk "threads [are] sent in Balls into all places that trade thither, purposely for to make Cables."27 Dampier, ever curious, apparently found their manufacture so interesting that he made some cable himself, mentioning that in Achin (Afghanistan) it was called 'Coire' cable, which lasted 'very well.' Edward Barlow also refers to the coconut cable found in the Maldives as 'coir', "a thread of yarn made of the husk of cocoanuts".28

The husk had some other uses as well. Navarette explains that in Indonesia, "they make a sort of Okam [oakum, put between boards and sealed with tar] to caulk Ships, and make Ropes, and good Match [piece of rope treated to burn slowly for firing guns] for all sorts of firearms which the Musketiers there make use of."29 Raveneau de Lussan and Dampier both note that the Spanish caulk their ships with this sort of oakum as well.30 Dampier says it "is more serviceable than that made of Hemp, and they say it will never rot."31 de Lussan goes adds that while the regular caulk "rots in the water in sea than a year's time, ...the other [palm fiber-based caulk] is fed by it, and waxeth green."32 Dampier adds that the husk is woven into a 'coarse cloth' which is used as sails in Ceylon, although he hadn't seen them and isn't sure it is the same sort of palm tree. (This likely refers to material made from date palms, not coconut palms, something John Atkins discusses in the General History of the Pyrates.33)

The inner shell of the coconut also found uses. Francis Rogers says, "the hard shell ...serves for cups to drink out of"34.

Photo: Cleveland Museum of Art - Carved coconut in silver mount, ( c. 1630)

Dampier mentions this along with a variety of other coconut-based items. "The Shell of this Nut is used in the East Indies for Cups, Dishes, Ladles, Spoons, and in a manner for all eating and drinking Vessels. Well shaped Nuts, are often brought home to Europe, and much esteemed."35 William Funnell agrees that coconut shells "make very pretty Drinking-cups: It will also burn very well, and make a very fierce and hot Fire."36 Sailor Alexander Hamilton says the in Melata (Ethiopia), some of the coconuts are so large that they hold "more than an English Quart Pot."37. Funnell, talking about sailing around South America states that some coconuts will hold 'near a quart'.38

Returning to coconuts as food, several coconut-based recipes can be found in the period sailor's accounts. Missionary Domingo Navarette said that people in the East Indies used coconut milk in "several ways, particularly to dress Rice." He adds that they make "an excellent preserve of it, which the Indians call Buchayo [Bukayo - a Filipino dessert of sweetened coconut strips]."39 Dampier says that in Guam, use coconut juice to "boil a Fowl, or any other sort of Flesh, and it makes very savory Broath. English Seamen put this water into boiled Rice, which they eat instead of Ricemilk, carrying Nuts purposely to Sea with them. This they learn from the Natives."40

A type of fermented alcohol is made from the sap of palm trees including coconut trees called by various names including toddy, tuba and sura. It is today referred to as palm wine.

Artist: Sylvain Meinrad Xavier Golbéry

Collecting Sap to Make Palm Wine (1803)

Note the Gourd Mounted to the Side to Collect Sap.

Sailing on the East Indiaman Scepter in 1697, Edward Barlow says that in most parts of India, "they make rack and sugar with called ‘todey’ [toddy]."41 Dampier describes the toddy he found while in Guam in 1686, which "looks like Whey. It is sweet and very pleasant, but it is to be drunk within 24 hours after it is drawn, for afterwards it grows sowre."42 He goes on to describe how toddy is made. "The way of drawing the Toddy from the Tree, is by cutting the top of a Branch that would bear Nuts; but before it has any Fruit and from thence the Liquor which was to feed its Fruit, distils into the hole of a Callabash [a bowl made from the rind of a fruit] that is hung upon it."43 Navarette similarly, although somewhat less descriptively, says, "Before the Coco-Nut itself sprouts out they draw an excellent Liquor from the nib of the Branch"44.

Palm wine can be distilled to create arrack, a liquor which was popularly used in the East Indies to make the mixed drink punch. Dampier says that no alcohol "is so much esteemed for making Punch as this sort [arrack], made [distilled] of Toddy, or the sap of the Coco-nut Tree, for it makes most delicate Punch; but it must have a dash of Brandy to hearten it, because this Arack is not strong enough to make good Punch of it self."45

While sailors didn't typically go into detail about the health benefits of the foods they encountered, their fascination with coconuts led them to discuss this facet of as well. Navarette said, "The Juice within, when the Coco is fresh, is wholesome and a pleasant drink for sick People, who roast the Coco and, after laying it out all Night in the Open Air, drink the Juice and find a good effect of it."46 Privateer Funnell noted, "This Milk being boiled with Rice, is accounted by our Doctors to be very nourishing; for which reason we often give of it to our sick Men."47

Professional opinions from the period support Funnell. Physician Hans Sloane said, "The Water contain'd in the Nuts [which are] not ripe, is very pleasant,

Photo: Jan van der Straet

Drinking Medicine, From A Man in Bed (1600)

cooling, and a natural Emulsion [mixture], good in Gonorhœas, Stoppage of Urine, Fevers, Inflammations, &c. and is the most pleasant cooling Liquor that I ever tasted"48. Fellow physician John Pechey advised that the water found naturally in a coconut "extinguishes Thirst, cures Fevers, clenses the Eyes and the Skin, purifies the Blood, purges the Stomach and Urinary Passages, relieves the Breast,

tastes pleasantly, and yields a great Nourishment." He said the milk manufactured by soaking fresh water with the meat of the coconut "is very good for killing Worms, eight Ounces of it being taken in a Morning, with a little Salt". And the fermented toddy "is very good for Consumptions,and excellent for Diseases of the Urine and Reins [kidneys]."49

Sloane cites another curious medical recommendation, although he clearly had reservations about it. "The inward hard Shell is made into Drinking-Cups, and is thought by some, to give an Alexipharmac [anti-poison] nervous Antiparalytic and Antiapoplectic [anti-stroke] Quality, to any Liquor standing in it, and makes Vessels of all Sorts, but this is not to be depended upon."50

Coconuts are one of the few fruits actually found in accounts relating to pirates, indicating pirates procured them for food. The first is found in the account of John Halsey who

Artist: Gotthilf Heinrich bon Schubert - Ashton's Escape, From Die Nieuwe Robinson Crusoe (1850)

"touch'd at Johanna [Anjouan, Comoros Islands], and there took in a Quantity of Goats and Coco Nuts for fresh Provisions"51. The second comes from prisoner Philip Ashton's account of his time as a prisoner of Edward Low. Ashton was sent ashore on an island off Honduras to gather them for the pirates. He used his freedom from the ship to escape from the pirates:

"I began to make up to the Edge of the Woods; when the Cooper spying me, call'd after me, & asked me where I was going; I told him I was going to get some Coco-Nuts, for there were some Coco-Nut Trees just before me. So soon as I had recovered the Woods, and lost sight of them, I betook my self to my Heels, & ran as fast as the thickness of the Bushes, and my naked Feet would let me."52 Once Ashton had made himself a castaway, he dolefully explained that while the coconuts were available to him, "I could have no Advantage from [them], because I had no Way of coming at the Inside."53

The third connection between pirates and coconuts also comes from a castaway, Richard Hawkins, who escaped from Francis Sprigg's crew near Roatan, Honduras, where he "fetch'd Plenty of Cocoa-Nuts"54. Unlike Ashton, he apparently had tools to split them open.

1 Philip Ashton, Ashton's Memorial, 1726, p. 46-7; John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 48-9; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 186, 188, 189, 208, 211, 372-3, 375, 431, 467-8 & 469; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V1, 1712, p. 316-7 & 449; Cooke, A Voyage..., V2, 1712, p. 9 & 41; William Ambrose Cowley, "Cowley's Voyage Round the World", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 15, 16 & 18; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 76; Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 76, 291-6, 303, 474 & 475-6; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 60-2; Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 4, 23-4, 124-5 & 181; Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 66-7; Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 40, 56, 72, 998, 135-6, 143 & 181; Raveneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 357; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, V1, p. 245 & 381; Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 130, 467; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 158; Bartholomew Sharp, "Captain Sharp's Journal of His Expedition", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 33; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 189 & 464; & Nathaniel Uring, The Voyages and Travels of Captain Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 106; 2 Dampier, pp. 291-6 & 474-5, 3 Francis Rogers, p. 158, Dampier, p. 291 & Cowley, p. 17; 5 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, 1707, p. 75; 4 Francis Rogers, p. 158, Dampier, p. 291 & 474, 5 Crowley, p. 17; 6 Dampier, p. 294; 7 Funnell, p. 60; 8 Dampier, p. 292; 9 Dampier, p. 296; 10 Dampier, p. 294; 11 Funnell, p. 61; 12 Atkins writing in Defoe [Charles Johnson], p. 186; 13 Domingo Navarrete, The Travels and Controversies of Friar Domingo Navarrete 1618-1686, 1962, p. 110; 14 Barlow, p. 189; 15 Atkins writing in Defoe [Charles Johnson], p. 186; 16 Francis Rogers, p. 158; 17 Dampier, p. 295; 18 Funnell, p. 61; 19 Funnell, p. 60; 20 Shelvocke, p. 189; 21 Funnell, p. 61; 22 Francis Rogers, p. 158; 23 Navarrete, p. 98; 24 Francis Rogers, p. 158; 25 Funnell, p. 60-1; 26 Dampier, p. 294-5; 27 Dampier, p. 295; 28 Barlow, p. 381; 29 Navarrete, p. 98; 30 Dampier, p. 295 & de Lussan, p. 357; 31 Dampier, p. 295; 32 de Lussan, p. 357; 33 Atkins writing in Defoe [Charles Johnson], p. 186; 34 Francis Rogers, p. 158; 35 Dampier, p. 294; 36 Funnell, p. 61; 37 Hamilton, p. 381; 38 Funnell, p. 60; 39 Navarrete, p. 97; 40 Dampier, p. 294; 41 Barlow, p. 469; 42,43 Dampier, p. 293; 44 Navarrete, p. 97; 45 Dampier, p. 293; 46 Navarrete, p. 97; 47 Funnell, p. 60; 48 Sloane, p. 9; 49 John Pechey The Compleat Herbal, 1707, p. 246; 50 Sloane, p. 8; 51 Defoe [Johnson], p. 467; 52 Ashton, p. 42; 53 Ashton, p. 46; 54 “59. Richard Hawkins' account...", Fox, p. 303

Cucumber

(Cucumus sativus)

Called by Sailors: Cucumber

Appear: 2 Times, in 2 Unique Ship Journeys from 2 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Barbados & Salvador, Brazil

Cucumbers are one of several fruits which are sometimes thought to be vegetables. (Others include tomatoes, which are not found in the period sailors accounts and pumpkins, which are.) Cucumbers were so common to the English sailor that they don't rate a description in their accounts, even when by the usually descriptive William Dampier. In fact, their familiarity led them to be used by several sea authors to describe other fruits which were likely less familiar to European readers.2

Botanist John Gerard says that there are "divers sorts of Cucumbers; some greater,others lesser; some of the garden, some Wilde, some of one fashion, and some of another". He goes on to describe them as "long, cornered, rough, and set with certaine

Types of Cucumbers, From The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, by John Gerard, p. 910 (1636)

bumpes or risings, greene at the first, and yellow when they be ripe, wherein is contained a firme and sollid pulpe or substance transparent, or thorough shining... The seeds be white, long, and flat."3. He includes images of three different types of cucumbers in his book (seen at left). French botanist Louis Lémery says "they are

usually yellowish, sometimes white, and at other

times green."4 Botanist John Parker identifies six different types including the long green, short, long yellow, French, Dantsicke [Danzig] and Muscovie [Muscovy]. His names seem to either refer to the size of the cucumber or the location where they are found. Parker describes Danzig cucumbers as small, typically being made into pickles and the Muscovy as "no bigger than small Lemons."5

Talking about their flavor, physician and former sailor William Hughes says that those found found in the New World "are more delicious in taste ...because the Sun doth better concoct them."6 For the most part, however, the period botanical and physician authors do not discuss their taste, perhaps because they were so familiar or possibly because they don't really have a lot of flavor. Lémery does mention that cucumber seeds are "agreeable enough to the Taste."7

Much is said about how they can be prepared and consumed. Parkinson, referring to them as 'cowcumbers' explains:

Photo: M. G. Moscatello - Sliced Cucumber

Some use to cast a little salt on their sliced Cowcumbers, and let them stand halfe an houre or more in a dish, and then poure away the water that commeth from them by the salt, and after put vinegar, oyle, & c. thereon, as every one liketh: this is done, to take away the overmuch waterishnesse and coldnesse of the Cowcumbers.

In many countries they use or eate Cowcumbers a wee doe Apples or Peares, paring and giving them slices of them, as we would to our friends of some dainty Apple or Peare.

The pickled Cowcumbers that come from beyond the Sea, are much used with us for sawce to meate all the Winter long.8

Couching his suggestions in medicine, Lémery says "you may also mix some other things with them to help digestion, such as Onions, Salt, Pepper, and other things of the like Nature."9 Gerard suggest, "The fruit cut in pieces or chopped as herbes to the pot, and boiled in a small pipkin with a piece of mutton, being made into potage with Ote-meale, even as herb potage are made, whereof a messe [meal] eaten to break-fast as much to dinner [lunch], and the like to supper"10.

Cucumbers had a significant place in medicine at this time. Gerard identifies the humoral qualities of cucumbers as cold and moist in the second degree.11 Hughes suggests that the cucumbers found in the West Indies "are not so cold" as those of Europe.12 Lémery

Photo: Wiki User Bff - Cucumber on Plant (Cucumis Sativus)

talks about the Paracelsian principles which include "a little Oyl, much Phlegm, and

an indifferent measure of essential Salt." He also says that cucumbers 'allay the sharpness of Humors, and too great a Fermentation of Blood [one of the bodily humors].13

Medicinally, this fruit is a mixed bag. Parkinson suggests that "rawe or greene Cowcumbers are fittest for the hotter time of the yeare, and for hot stomackes, and not to be used in colder weather or cold stomackes, by reason of the coldnesse, whereby many have been overtaken."14 Lémery similarly suggests that "in hot Weather [they] are proper for young

Persons of an hot and bilious Constitution; but

weak and tender People, that have a bad Stomach, or are of a phlegmatick Temper, ought

to abstain from them."15 (Such comments are grounded in the hot and cold humoral properties believed to be a part of food as well as the body.)

Gerard starts out in the same vein, noting that cucumbers are "good for the stomacke and other parts troubled with heat."16 He says that the potage (mentioned previously) "doth perfectly cure all manner of sauce fleame [?] and copper faces, red and shining fierie noses (as red as red Roses) with pimples, pumples, rubies, and such Iike precious faces."17 However, he quickly turns against them as food, warning that they don't produce "any nourishment that is good, insomuch as the unmeasurabie use thereof filleth the veines with naughty cold humors." He further warns that they "putrifie soon in the stomacke, and yeild unto the body a cold and moist nourishment, and that very little, and the same not good."18

The cucumber seed, which had the backing of Galen as a useful 'cold' remedy, gets a better reputation than the fruit itself. Gerard says the is not as cold as the whole fruit. "It openeth and clenseth, provoketh urine, openeth the stoppings of the liver, helpeth the chest and lungs that are inflamed; and, being stamped and outwardly applied in stead of a clenser, it maketh the skin smooth and faire."19 Parkinson says that the seeds are widely used in medicines designed "to coole, and a little to make passages of urine slippery, and to give ease to hot diseases."20

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 312; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 72; 2 See, for examples, John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea, Brazil and the West Indies, 1735, p. 48; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 158 & William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969 p. 268; 3 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 909; 4 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 29; 5 John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1904, p. 524; 6 William Hughes, The American physitian, 1672, p. 22; 7 Lémery, p. 28; 8 Parkinson, p. 524-5; 9 Lémery, p. 28; 10 Gerard, p. 912; 11 Gerard, p. 911; 12 Hughes, p. 22; 13 Lémery, p. 28; 14 Parkinson, p. 525; 15 Lémery, p. 28; 16 Gerard, p. 911; 17 Gerard, p. 912; 18 Gerard, p. 911; 19 Gerard, p. 911; 20 Parkinson, p. 525

Date

(Phoenix dacteylifera)

Called by Sailors: Date

Appear: 10 Times, in 10 Unique Ship Journeys from 8 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Algiers, Algeria; Anjouan, Comoros Islands, Madagascar; Tunis, Tunisia; Mussendon & Quriyat, Oman; Basra, Iraq; Rajpur, India; Mocha, Yemen; and Pisco, Peru

English sailors had been plying the Mediterranean for centuries by the time of the golden age of piracy, so dates were familiar to sailors. Likely because of this, most sailor accounts merely include them in lists of fruits without bothering to give much in the way of details.

However, sailor Alexander Hamilton, who spent about 30 years in the East Indies as a merchant sailor and commander, provides some interesting observations about this fruit, referring

Ordinary Date Tree, From Theatrum Botanicum, By John Parkinson (1640)

to the dates in Basrah (modern Iraq). He says dates there are "the most plenty and useful of all their Fruits... which support and sustain many Millions of People, who make them their daily Food, and they are wonderfully nourished by them. Bassora [Basrah] exports yearly for foreign Countries, above 10,000 Tuns of Dates, which employ Abundance of Seamen for their Exportation, besides many more Poor in gathering and packing them in Mats made of the Leaves of the Date Tree, and like wise in drying them." He noted that he purchased approximately 160 Pounds of 'wet Dates' for 2 shillings 3 pence.2

There are explicit pirate connections to dates. In October of 1698, pirate captain John Hore's men captured a small fishing village in what is today Mussendon, Oman where they "got good store of dates and salt fish", presumably for food.3 While in the East Indies, pirates Edward England, Henry Every and William Kidd each procured dates during their travels.4

With the exception of Peru, all the dates found in sailors accounts come from the East Indies. Botanist John Gerard notes "Date trees grow plentifully in Affrica and Egypt; but those which are in Palestina and Syria be the best: they grow likewise in most places of the East and West Indies,where there be divers sorts as well wild as tame or manured."5 In fact, they come from the Mediterranean region, thriving in dry, humid, warm climates.6 Amedee-Francois Frezier may have found them in Peru7, but it was thanks to plants which had been brought there and cultivated by Spanish travellers.

French botanist Louis Lémery describes a date as "oblong, round, pulpy, yellow Fruits, a

Photo: Denise Krebs - Varieties of Dates

little more thick than long... It contains a very hard, long, round, or greyish stone or kernel, wrapped up in a fine thin and white skin"8. Botanist John Parkinson says the fruit is initially green, then reddens as it ripens. He suggest there was quite some variety in ripe dates. "[S]ome sorts are small, and some great, some of a soft substance, some firmer and harder, some whitish, some yellowish or reddish, or blackish, some round like an Apple, others long with the roundnesse, some having the top soft, and some none at all"9. Like his contemporaries, botanist John Gerard says the fruit is "long and round ...and of a yellowish red colour; wherein is contained a long hard stone, which is instead of kernel and seed"10. Lémery adds that the best date is large and "full of Juice, yellow, ripe, of a firm pulp, that is easily separated from its Stone or Kernel, and has not been Worm-eaten; those are the best that come from the Regency of Tunis and Barbary."11

Gerard rather confusingly describes ripened dates to be "in taste sweet, and many times somewhat harsh"12. Lémery's description of the taste helps to clarify this a bit. He first notes that dates are 'agreeable to the taste', later adding that "they never become sweet in those parts of Spain that border upon the Sea, but retain an unpleasant and harsh taste."13 Parkinson says some dates "are so sweete and lushious that they will not keepe long... others will abide whole for a long time, and [are] fit to be sent into any farre Country"14.

Humorally, Gerard says dates are 'dry and binding', although "the soft moist and sweet ones" are less so. "The Dates which grow in colder regions, when they cannot come to perfect ripenesse, if eaten too plentifully, they fill the body full of raw humors... The bloud which is ingendred of Dates in mans body is altogether grosse, and somewhat clammy"15. Such blood (one of the four bodily humors) would be considered unhealthy and therefore detrimental to health. From the Paracelsian perspective, Lémery says dates "contain much Oil, Phlegm, and essential Salt."16

Medicinally, Lémery suggests that dates have good and bad qualities. On the plus side, he feels they "are of a moistning and qualifying [diminishing] Nature, very nourishing, stop a Cough, are a little

Photo: Wikipedia User Noblevmy - Ripe Dates on the Tree

detersive [cleansing], astringent [contracting], and proper for Diseases of the Throat; they are looked upon to be good for strengthning a Child in the Mother's Womb." However, he immediately adds, "They produce a great many ill Humours, and therefore those who feed upon them become full of the Scruvy, and soon lose their Teeth; they are hard of Digestion, and cause Obstructions in the Bowels." Generally, however, he seems to think they are good. "They agree at all times, with any Age, and with all sorts of Constitutions, provided they be moderately taken."17

Parkinson gives a similar good/bad accounting of a date's effect on health. He begins by stating that "unripe Dates are very harsh and binding, and the ripe also when they are fresh more than when they are dry". Yet he doesn't consider these qualities to necessarily be bad. Because of their binding nature, such dates would stop "vomitings, and the laske [looseness] of the belly, and stay also the bleeding and falling downe of the fundament [anus] and piles [hemorrhoids]". Once they are dried, Parkinson says they "helpe the hoarsenesse and roughnesse of the throate, the sharpe cough by reason of the sharpe rheume falling on the breast and lungs... alayeth the force of hot agues, and stayeth spittings of bloud, the paines in the stomacke and bowels, because of a fluxe". However, Parkinson also says when dates are "taken too often, or too liberally, they breed head ach, and a kinde of peturbation of the braine, like unto drunkenesse"19. Yet, on the whole, he has a generally favorable opinion of them medicinally.

Gerard agrees that they are hard to digest. He says that unripe dates also "ingender wind, and oftentimes cause the Leprosie."18 He goes on to review a variety of recommendations by other medical authors which generally agree with their drying ability. Among those he mentions - stopping bloody fluxes, easing problems of the throat and having binding and 'emplastick' [adhesive] qualities. He explains, "There are made hereof both by the cunning Confectioners & Cooks, divers excellent, cordial, comfortable and nourishing medicines, that procure lust of the body very mightily."18

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 58 481; John Covel, Diary, Early Voyages in the Levant, Thomas Dallam, ed., 1893, p. 120; “37. Henry Watson, from Narrative of Mr. Henry Watson, who was taken prisoner by the pirates, 15 August, 1696”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 177; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 186; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 68; John Franklin Jameson, Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period – Illustrative Documents, 1923, p. 175 & Daniel Defoe [Charles Johnson], A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 130; 2 Hamilton, p. 79; 3 "37. Henry Watson...", Fox, p. 177; 4 “65. Deposition of Samuel Perkins...", Jameson, p. 175; “71. Deposition of Benjamin Franks...", Jameson, p. 193 and Defoe [Johnson], p. 130; 5 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie fof Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1517; 6 "How to Grow and Care for Date Palm Trees at Home", Masterclass.com, gathered 3/9/22; 7 Frezier, p. 186; 8 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 55; 9 John Parkinson, Theatrum Botanicum the Theater of Plants, 1640, p. 1545; 10 Gerard, p. 1517; 11 Lémery, p. 55; 12 Gerard, p. 1517; 13 Lémery, p. 56; 14 Parkinson, p. 1545; 15 Gerard, p. 1518; 16,17 Lémery, p. 55; 18 Gerard, p. 1518; 19 Parkinson, p. 1547

Durian

(Durio)

Called by Sailors: Durean, Durian

Appears: 5 Times, in 5 Unique Ship Journeys from 2 Sailors Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Mindanao, Philippines; Banda Aceh, Indonesia; Bengkulu, Sumatra; Malacca and Trenggannu, Malaysia

Durians caught the attention of two sailors. Sailor Alexander Hamilton mentions them as foods which were available in Malaysia. William Dampier found them in the Philippines, Sumatra and Indonesia during his various voyages. Both found this fruit interesting enough to give a description of it.

Dampier says durians are "about the Bigness of a large Pumpkin, covered with a thick green rough Rind." He goes on to note that it can only be eaten when ripe, indicated by the rind

Photo: Rod Waddington - Durian Fruit in Yannan, China

turning yellow, when it opens at the top "and sends forth an excellent Scent." Inside the rind are "several small Cells, that inclose a certain quantity of the Fruit, according to the bigness of the Cell, for some are larger than others. ...‘Tis as white as Milk, and as soft as Cream"2. Along similar lines, Hamilton notes the "Pulp like Cream in Colour and Consistence."3. Dampier adds that "Within the Fruit there is a Stone [pit] as big as a small Bean, which hath a thin Shell over it."4

Durians have a unique quality that can impact the flavor. As Hamilton explains, the durian is the fruit is "offensive to some Peoples Noses, for it smells very like human excrements, but when once tasted, the Smell vanishes."5 Dampier is a bit less harsh, explaining that "those who have not been used to eat them, will dislike them at first, because they smell like roasted Onions."6

The smell of the fruit aside, Hamilton calls it "excellent Fruit" and says it is "delicious in Taste"7. Dampier says "the Taste [is] very delicious as those that are accustomed to them". He goes on to warn that a durian must be eaten within a day or two of being opened, otherwise, "it putrifies [rots], and turns black, or of a dark colour, and then it is not good. Those that are minded to eat the Stones or Nuts, roast them, and then a thin Shell comes off, which incloses the Nut; and it eats like a Chestnut."8

Humorally, Portuguese doctor Cristobal Acosta, a 16th century pioneer in the use of East Indies plants in medicine, says that a durians "is hot, and humid and very easy to digest."9 German botanist Georg Rumphius working for the Dutch East India company agrees with this assessment.10

Acosta doesn't seem to regard the fruit as having any specific healing properties, not mentioning it being effective for treating any specific illness.

Photo: Wiki User DXLINH - Durian Tree with Fruit

Sailor Hamilton (who likely knew little about its medicinal properties) says, "The Pulp or Meat is very hot and nourishing, and instead of surfeitings [causing an excess of fluid in the body], they fortifie the Stomach, and are a great Incentive to Wantonness."11

Rumphius, on the other hand, has little good to say about the effect of a durian on health. He says that it will "stoke the blood and heat up the bowels" and the seeds "cause a rough and hoarse throat, along with shortness of breath, which is why it is better to throw them away. It is bad for the same reason to eat Duriuns on a full stomach because they will then easily rot." He goes to explain that eating too many will "cause bloody ulcers, carbuncles [red, pus-filled bumps], fevers and Bloody flux, which is why they should be particularly avoided by people who have any defect of the bowels, or exterior ulcers, wounds or carbuncles, for they inflame them all the more. Otherwise, the Duriuns purge the Urine, makes one sweat, and stir people to lewdness"12.

1 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 311; William Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, pp. 124 & 181; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 381; 42 Dampier, p. 319; 3 Hamilton, p. 381; 4 Dampier, p. 320; 5 Hamilton, p. 381; 6 Dampier, p. 319-20; 7 Hamilton, p. 381;8 Dampier, p. 320; 9 Cristobal Acosta, Tractado de las Drogas y Medicinas de las Indias, 1578, translated from Spanish by the author, p. 229; 10 Georgius Everhardus Rumphius, The Ambonese Herbal, E. M. Beekman, Ed, Vol1, 2011, p. 338; 11 Hamilton, p. 381; 12 Rumphius, p. 339

Fig

(Ficus carica)

Called by Sailors: Fig

Appears: 14 Times, in 12 Unique Ship Journeys from 9 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Marseilles, France; Rota, Spain; Messina, Italy; Algiers, Algeria; Surat, India; Rattan, Honduras; Madeira, Portugal; Hiloe, Chile; Chepillo Island, Panama

Figs were clearly well-known among the sailors. Only Dampier provides any description of the fruit. They were so well known that several of the other authors use figs to describe other exotic fruits with which they weren't familiar.2 To further complicate their description, botanist Louis Lémery states notes there are several different kinds of figs which came in a variety of sizes, forms, colors and tastes.3

Dampier give a description of what he calls a 'wild fig' tree found on Timor in the fall of 1699.

The Fruit grows, not on the Branches singly, like those in America, but in Strings and Clusters, forty or fifty in a cluster, about the Body and great Branches of the Tree, from the very Root up to the Top. These Figs are about the bigness of a Crab-Apple, of a Greenish Colour, and full of small white Seeds; they smell pretty well, but have no Juice or Taste; they are ripe in November.4

The only reason he describes these particular figs is because he considers them unusual. There are a couple of other comments of minor interest regarding figs in the sailors accounts. When Edward Barlow was aboard the navy ship Augustain in the Mediterranean in 1661, he commented that "[Algiers] yieldeth little commodities for traffic [merchant shipping], yet the country is good and fruitful in provisions, for you may buy a hundredweight of good figs for six shillings halfpenny English money."5

Photo: Forest and Kim Starr - Ficus aurea fruit, Boynton Beach, Florida,

The pirate-related account comes from a former prisoner of Edward Low who had recently escaped to the islands around Roatan in Honduras. Stranded on these islands, Philip Ashton explained, "There are Wild-Figs, and Vines in abundance; these I chiefly lived upon, especially at first."6 Ashton is likely referring to strangler figs (Ficus aurea), an air plant which attaches to existing trees and then takes root. These trees produce fruit continuously throughout the year. Hans Sloane describes a type of fig tree he found in Jamaica which is also apparently a strangler fig based on his description. He says the fruit is "spherical or perfectly round, on the outside, and are within full of red Grains or Seeds like those of our Figs"7.

Artist: Bartholomeo Bimbi - Figs (1696) Botanist John Parkinson discusses the fig trees which grow in England, identifying three types of them: Algerian figs ('blewish when ripe'), Spanish figs ('the white, ordinary kinde') and a dwarf fig ('excellent good Figges and blew'). The names of the first two types correspond with places some of the sailors found figs in their accounts. Parkinson notes that Algerian figs are "very like unto a small Peare, full of small white grains or kernels within it... and very mellow or soft, that it can hardly be carried farre without bruising."8 He says that the dwarf figs are smaller and more tender.

Flavorwise, Lémery advises, "whatever kind they be, you must choose such as are soft, juicy, and of good taste; those that have a tender and delicate Coat are more easily digested than others; however, they ought not to be eating 'till the Skin is taken off, and that they are full ripe."9 Parkinson mentions that the Algerian figs he describes are "of a very sweete taste when it is ripe"10. Dissenting from the popular opinion, Sloane advises that the strangler figs he found in Jamaica "are of an insipid [not very flavorful] Taste."11

As food, Parkinson says they can be served with raisins and blanched with almonds as a Lenten dish. Ripe figs, "fresh gathered, are eaten of divers with a little salt and pepper, as a dainty banquet to entertaine... which seldome passeth without a cup of wine to wash them down."12

Photo: Eric Hunt - Sliced Open Figs (Ficus carica)

Humorally, botanist John Gerard suggests green figs are 'somewhat warme and moist', while ripe figs "are hot almost in the third degree,and withall sharpe and biting."13 (Medicine and plant humoral qualities were divided into degrees, typically between one and three (and, in extreme cases, four), although this seems to have been subjective.)

Medicinally, Lémery says figs "are very nourishing, quench thirst, allay sharp humors in the breast; they are likewise looked upon to be good against the Stone in the Kidneys, and to resist poisons. They make Gargarisms [gargles] of them for Distempers of the Throat and Mouth, and are also outwardly applied for to soften, digest [break down] and hasten supporation [formation of pus - believed to be the bad humors leaving a wound.]"14 He warns that they cause gas and 'crudities' and can lead to a bloody flux. Gerard cites several of these properties as well, adding that they 'ripen flegme', which refers to processing the humor phlegm so that it is more useful to the body, by "causing the same to be easily spit out, especially when they bee sodden with Hyssop, and the decoction drunke."15 Spitting was seen as a good way to rid the body of the humor phlegm when it was unwanted.

1 Philip Ashton, Ashton's Memorial, 1726, p. 46; John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 26; John Baltharpe, The straights voyage or St Davids Poem, 1671, p. 14, 40 & 64; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 58 & 270; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 23; Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 69; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 172-3; Raveneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 330; Basil Ringrose, The Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp, And Others, in the South Sea, 1684, p. 71; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 178 & 233; 2 See for example, William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 314; Jean Baptiste Labat, Nouveau Voyage aux Isles de l'Amerique, Tome 4, 1724, p. 343 & Francis Rogers, p. 158; 3 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 21-2; 4 Dampier, Part II, 1703, p. 69; 5 Barlow, p. 58; 6 Ashton, p. 46; 7 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, 1707, p. 139; 8 John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1904, p. 566; 9 Lémery, p. 22; 10 Parkinson, p. 566; 11 Sloane, p. 139; 12 Parkinson, p. 567; 13 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie fof Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1517, p. 1511; 14 Lémery, p. 22; 15 Gerard, p. 1511

Grape

(Vitus)

Called by Sailors: Grape, Currans

Appears: 22 Times, in 18 Unique Ship Journeys from 10 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Alicante, Cadiz & Rota, Spain; Sardinia, Italy; Madeira, Portugal; Tenerife, Canary Islands; Cape Corso Castle, Africa; Jamestown, St. Helena; Qeshm Island, Iran; Basra, Iraq; Surat, India; Aden and Mocha, Yemen; Java, Indonesia; Côn Sơn Island, Vietnam; Cape of Good Hope, Africa; Barbados; Isla del Carmen & Isla Buey, Mexico; Salvador, Brazil

As with other fruits familiar to the sailors during this period, grapes only occasionally get more than a passing mention in their accounts. The botanists of this time acknowledged that there were a large variety of types of grapes. Louis Lémery states that grapes can be white, red and black,

Artist: Jacob van Es - Still-Life of Grapes Plums and Apples (17th c.)

although he does not consider one to be any better than the other.2 John Parkinson explains, "There is so great diversities of Grapes, and so consequently of Vines that bear them, that I cannot give you names to all that here [in England] grow with us"3. He goes on to list 23 different grape varieties, describing many of them. However, this article focuses on those described by the period sailors.

When sailor Francis Rogers visited Madeira, he noted that "some of the white [grapes are] as large as a pigeon’s egg and oval, some of the bunches of a prodigious magnitude; I have heard of 20 lbs or more, extreme luscious and pleasant and wholesome, both black and white."4 Sailor Edward Barlow stopped at an island near Hormuz in 1687 where he mentioned finding grapes "which have no stones in them like other raisins, they being of a pale whitish colour and but small fruit."5

William Dampier mentioned finding an unusual fruit which appeared to be a type of grape in Vietnam. "The Grape-tree grows with a strait Body, of a Diameter about a Foot or more, and hath but few Limbs or Boughs.

Grapes Varieties, From Paradisi in Sole, By John

Parkinson (1629)

Key: 1. The small blacke Grape. 2. The great blew Grape.

3. The Muscadine Grape. 4. The Burlet Grape. 5. The

Raysins

of the sunne Grape. 6. The Figge tree

The Fruit grows in Clusters, all about the Body of the Tree, like the Jack, Durian, and Cacao Fruits. There are of them both red and white. They are much like such Grapes as grow on our Vines, both in shape and colour"6. What type of grape this is is uncertain; it may be Vitis balansana, a grape variety native to Vietnam. Dampier also mentions another 'grape-tree' in one of his books, but that one is clearly a seagrape, not a true grape.

The sailor's comments on the flavor of the grapes they found were generally positive, if a little terse. Talking about those Francis Rogers discovered at Madeira, he said they "are most delicious"7. Barlow noted that in 1676 the island of Tenerife had "very long and pleasant vineyards which produce a very fine grape"8. He noted that the grapes on the island near Hormuz were "excellent"9. Dampier said the fruit he found on his 'grape-tree' "are of a very pleasant winy taste."10 The comments made on the flavor of grapes by the botanists are similar. In his general description of the generic grape, Parkinson simply says that better cultivated grapes are "fairer and sweeter" than those which don't receive as much care.11 Lémery gives recommends that those who each to eat grapes should choose "such as are of a sweet and agreeable taste", going on to note that all types will "agree with every Age and Constitution, provided they not be used to excess".12

In addition to eating grapes off the vine, they could be prepared as raisins (or, what are mistakenly called currants in some periodicals). Since these dried grapes were one of the few fruits carried to sea, they are discussed in their own section. Not surprisingly, grapes fermentation is one of the most discussed methods of preparing this fruit. Madeira, where Francis Rogers found grapes, was famous for their sweet wine which the many Englishmen liked. Funnell mentions the Dutch at the Cape of Good Hope "make a very

pretty and pleasant Wine in great quantities, which by Retale is commonly sold at eight Pence a

, Frncesco Bassano the Younger, 16thc.jpg)

Artist: Francesco Bassano the Younger - Making Wine, Septiembre (Libra) (16th c.)

Quart."13 When Barlow visited Tenerife, he said they made "a delicious and rare wine, yet there is some indifferent wine made here also."14

Humorally, the authors are somewhat vague about the qualities associated with grapes. According to Parkinson, "The Vine hath in it divers differing and contrary properties, some cold, some hot, some sweete, some sower, some milde and some sharpe, and some moistening, and others drying"15. He goes on to list the properties of various parts of the grape vine, but when he gets to the fruit, he fails to give much detail on the fruits' specific humoral properties. Botanist John Gerard, usually one to list the humors and their degrees for food, is also somewhat shy when it comes to grapes. He does say, "Sweet Grapes and such as are thorow ripe are lesse hurtfull: the juice is hotter, and easilier dispersed. They also sooner passe through the belly, especially being moist, and most of all if the liquor with the pulp be taken without the stones [seeds] and skin,as Galen saith."11 So the Galenist view appears to be that grapes are hot and moist. Lémery is much more direct, listing the grapes as containing "much Oil, Salt and Phlegm."16

If some botanical authors are a little timid in assigning grapes specific humoral qualities, they spare nothing in tying their medicinal impact in with the body's humoral processes.

Botanist John Gerard says that raw grapes upset the stomach, particularly when they have a sour flavor. "[S]uch kindes of Grapes do very much hinder the concoction of the stornacke; and

while they are dispersed through the liver and veins they ingender cold and raw juice, which cannot

Photo: Rosie Hattersley - Malvasia Grapes (A Varietal Popular on Madeira)

easily be changed into good bloud." This is a reference to the body processing the grapes in an effort to turn them into the bodily humor Blood, one of Galen's humors.

Gerard continues, saying that medicinally grapes "do coole and mightily binde: they stay bleeding in any part of the body: they are good against the laske [looseness of the bowels], the bloudy flix [bloody flux], the heart-burne, heate of the stomacke, or readinesse to vomit. ...they be moreover a remedie for the inflammation of the mouth and almonds of the throat [tonsils], if they be gargled, or the mouth washed therewith."17

Lémery advises that grapes "open the Body, create an Appetite, are very Nourishing, excite seed, and qualify the sharp Humours of the Breast. He also says that grapes 'qualifie sharp salts which prick the Breast'. He adds that a ripe grape is "of a softening and laxative Nature; the Reason whereof is that [after ripening] it contains more watry Parts... and its oily principles... are also in a better Condition to loosen the Fibres of the Stomach and Bowels, and to dilate the excrements contained therein."18 He is referring to to the Paracelsian principles of salt and oil in these comments. It is notable that he finds them loosening and opening while Gerard finds them binding and contracting.

1 John Baltharpe, The straights voyage or St Davids Poem, 1671, p. 14 & 30; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 211, 283, 312, 379 & 480-1; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 392; Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 48 & 107; Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 107; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 293-4; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 52 & 438-9; Jean-Baptiste Labat, The Memoirs of Pere Labat, 1693-1705, John Eadon ed, 1970, p. 262; Stephen Martin-Leake, The Life of Sir John Leake, Rear-Admiral of Great Britain, Vol 1, 1920, p. 269; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, pp. 174, 178, 191 & 231; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 371; Nathaniel Uring, The Voyages and Travels of Captain Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 106; 2 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 39; 3 John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1904, p. 563; 4 Francis Rogers, p. 233; 5 Barlow, p. 379; 6 Dampier, 1699, p. 392; 7 Francis Rogers, p. 233; 8 Barlow, p. 283; 9 Barlow, p. 379; 10 Dampier, 1699, p. 392; 11 Parkinson, , Paradisi..., p. 392; 12 Lémery, p. 38; 13 Funnell, p. 293-4; 14 Barlow, p. 283; 15 Parkinson, Theatrum botanicum, 1640, p. 1557; 16 Lémery, p. 39; 17 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie fof Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1517, p. 876; 8,9 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 39; 10 Lémery, p. 40;

Guava

(Psidium)

Called by Sailors: Gorifesies, Gufous, Goyaves, Guava, Guayava, Guavos, Jambo Malacca, Savintu

Appears: 25 Times, in 18 Unique Ship Journeys from 11 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Tenerife, Canary Islands; Santiago, Cape Verde Islands; Cape Corso Castle, Africa; Principe; Goa, India; Banda Aceh, Java & Timor, Indonesia; Bengkulu, Sumatra; Mindanao, Philippines; Haiphong, Vietnam; Guam; Barbados; Jamaica; Roaton, Isla Buey & Isla del Carmen, Mexico; Roaton, Honduras; Ilha Grande, Salvador & St. Catherine, Brazil; Hiloe, Chile & Coiba, Panama; Chepillo Island, Costa Rica

Guavas are found in every type of sailor account, indicating how ubiquitous they were in the sailor's world during the golden age of piracy. Privateer Edward Cooke says the Spanish call one type of fruit guayavas [guayaba is the Spanish word for guava] which the Peruvian natives refer to as savinto. Interestingly, he adds that what the Spanish refer to as guavas, the natives call 'pacay'. Pacay are actually a completely different fruit, commonly called ice cream beans. In fact, the Spanish actually refer to ice cream beans as 'guamas", meaning Cooke must have misheard the word.

Buccaneer William Dampier says the guava is "much like a Pear, with a thin rind; it is full of small hard Seeds". He adds that a guava "is ripe it is yellow, soft,

Photo: Wiki user Sarang - Guava, Psidium guajava fruit of Cuba

and very pleasant."2 While in Tonquin (Haiphong, Vietnam) in 1699, he noted that guavas "thrive here very well: but there are not many of" them.3 Privateer Edward Cooke serving aboard the Marquis, found guavas in Peru which he said were "as big as indifferent Apples, having a Paring [skin] like them, and in the Pulp abundance of small Seeds, less [smaller] than those of Grapes." He goes on to say that some have yellow skins with red flesh and others have green skins with white flesh.4 Dampier's description of guavas agrees with Cooke's. "There are of divers sorts, different in shape, taste and colour. The inside of some is yellow, of others red."5

Sloane divides the guavas he found on Jamaica into three types: the red Guava, the large white Guava and the small white Guava. He says that the first two have similar properties, while the smaller fruit is "white within"6. Of the red tree, he explains that they "are planted every where for their Usefulness, and grow naturally in the lowland Woods, or Plains in Barbados, the Caribe Islands, and jamaica."7 He notes that the white guava "grows in the Plains every where with the other Kinds, but more especially in the inland Parts of this Island [Jamaica]."8

Guavas appear in two pirate accounts. The first is from a description of São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón written by sea surgeon John Atkins for the General History of the Pirates, making it an indirect connection.9 The other comes from Richard Hawkins, a captive of pirate Edward Low, who found them after escaping from the pirates in Honduras.10

The flavor of guavas is mentioned a variety of times. In discussing the different colored guavas he encountered, privateer Cooke notes that the yellow fruit with red flesh "are [of] two Sorts; the one so sour, they cannot be eaten, the other sweet and pleasant.

Artist: Benedito Calixto

Goiabas (Guavas) (late 19th - early 20th c.)

" He adds that the green skinned guavas are much better than either of the red ones.11 Sloane is effusive in his praise for guavas. "The Fruit is counted extremely pleasant, delicious and wholesome, and may very deservedly take the first Place among the West-India Fruits, if eaten when thoroughly ripe."12 However, he also notes that those with white skins and white flesh are not as 'juicy or pleasant' as the other types.13 Sea surgeon Atkins complains that they have "an uncouth astringing Taste... [which is enjoyed by] Men whose Tastes are so degenerated, as to prefer Toad in a Shell, (as [Ned] Ward calls Turtle) to Venison"14. He was clearly not a fan.

Dampier says guavas are very pleasant, adding they are unusual because they can be eaten while they are still green. This is "a thing very rare in the Indies; the most [of this type of] Fruit, both in the East or West-Indies, is full of clammy, white, unsavory juice, before it is ripe, though pleasant enough afterwards [when it is ripe]."15

Dampier also provides a guava recipe. He says that the fruit "bakes as well as a Pear, and it may be codled [coddled - cooked in water just below the boiling point], and it makes good Pies."16 Surgeon Atkins, continuing to register his dislike of the fruit, says that while in Jamaica in June of 1723, he had them as "a Desart [dessert] ...[along with] other insipid or ill-tasted Fruit."17 Sloane writes that the red guava can be in "any Way boil'd, stew'd, or otherwise prepar'd, [and it] tastes yet more pleasantly."18 Along similar lines, botanist Georg Eberhard Rumphius says pear-shaped guavas "are also cut up sometimes, the central and grainy clump thrown away, and then stewed in Spanish wine and sugar, which will give you a pleasant dish"19.

From a humoral perspective, physician Sloane says guavas are hot and dry, which aids digestion.20 Curiously, physician William Hughes says the opposite, indicating that they are 'cooling', although he doesn't go

Photo: P. Jeganathan

Jungle Striped Squirrel Eating a Guava (Apparently the astringency doesn't bother it.)

so far as to indicate that this has property any connection to humors.21

Several sailors talk about the medicinal characteristics of guavas. Edward Barlow explains that guavas "are much like a pear and an excellent fruit against the flux [diarrhea]"22. This would make it binding or contracting. Buccaneer Dampier explains that "[w]hen this Fruit is eaten green, it is binding, when ripe, it is loosening."23

Agreeing with Dampier's assessment, Sloane says that guavas are "very astringent, they stop up the Belly if eaten in great Quantity, and the Seeds sometimes sticking on the Outside of the hard Excrement in coming thro' the Intestines, especially the Rectum, by their irregular sharp Angles will occasion great Pain there, and very often bring a Flux of Blood."24 He later expands upon this, stating that "the less ripe [the fruit is] the more astringent, and when they are very ripe, or soft and rotten, they loosen the Belly."25 Rumphius likewise says that pear-shaped guavas will "render one costive [constipated], wherefore they are good for people who suffer from diarrhea; one should not eat it before a meal because, as said, it will cause constipation: they are better after a meal, also in the morning on an empty stomach"26.

1 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 217 & 244; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 86, 211 & 312; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V1, 1712, p. 26; Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea..., V2, 1712, p. 15; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 311; Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 23-4, 124 & 181; Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 94 & 107; Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 10, 33 & 68; Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 72; Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 303; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 22 & 172-3; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 217-8; Raveneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 330; Daniel Defoe [Captain Charles Johnson], A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 185-6; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 356 & Nathaniel Uring, The Voyages and Travels of Captain Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 106; 2 Dampier, 1699, p. 222; 3 Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 23; 4 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, 1707, p. 161; 4 Cooke, V1, p. 203; 6 Sloane, p. 163; 7 Sloane, p. 161; 8 Sloane, p. 163; 9 Atkins writing in Defoe [Charles Johnson], p. 187; 10 Ed Fox, “59. Richard Hawkins' account of his capture by Francis Spriggs, from The British Journal, 8 August, 1724 and 22 August, 1724", Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 303; 11 Cooke, V1, p. 203; 12 Sloane, p. 161; 13 Sloane, p. 163; 14 Atkins writing in Defoe [Charles Johnson], p. 187; 15,16 Dampier, 1699, p. 222; 17 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 244; 18 Sloane, p. 161; 19 Georgius Everhardus Rumphius, The Ambonese Herbal, E. M. Beekman, Ed, Vol1, 2011, p. 404; 20 Sloane, p. 162; 21 William Hughes, The American physitian, 1672, p. 46; 22 Barlow, p. 86; 23 Dampier, 1699, p. 222; 24 Sloane, p. 161; 25 Sloane, p. 162; 26 Rumphius, p. 404

Jackfruit

(Artocarpus heterophyllus)

Called by Sailors: Jaca, Jack, Jarkes

Appears: 10 Times, in 7 Unique Ship Journeys from 3 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Malabar Coast, India; Sri Lanka Banda Aceh, Indonesia; Bengkulu, Sumatra; Kupang & Pante Macassar, Timor; Palau Sabuda, West Papaua & Mindanao, Philippines; Guam

The majority of the instances of this fruit in come from William Dampier's accounts. Dampier found Jackfruit while traveling in the East Indies. He mentions finding them when the bucaneer ship Cygnet stopped at Mindanao in 1686, during two East India merchant voyages he made in

Photo: Parchaya Roekdeethaweesab - Sliced Jackfruit

Indonesia in 1689 and while the Roebuck's exploratory trip was coming to an end in 1700 in the same area. Edward Barlow is a runner up for most mentions, listing jackfruit twice

among the edible fruits he encountered during his East Indies merchant voyages. One was made aboard the Sampson in 1692 when it stopped at Sri Lanka and the other aboard the Wentworth when it was off the Malabar Coast in India in 1697.2

Dampier gives a brief description of jackfruit, comparing it to a durian. While he says the the tree and manner of fruit growth are similar to durians, "the inside is different; for the Fruit of the Durian is white, that of the Jack is yellow, and fuller of Stones."3 He also mentions a type of wild jackfruit during his Roebuck voyage, noting that those were "brought hither by the Dutch and Portugueze; and most of them are ripe in September and October."4

French botanist Louis Lémery says the ripe fruit has a good scent and its "flesh is firm & divided into small cells full of 'chestnuts' a little longer & larger than dates, covered with a gray peel, white inside like the common chestnut"5. He says these 'chestnuts' "are surrounded by a yellowish flesh and are a little viscous, resembling the pulp of Dorion [durian]"5. German botanist Georg Rumphius found them in the East Indies while

Jackfruit and Tree, From The Ambonese Herbal,

By Georg

Eberhard Rumphius (1642)

cataloguing the plants he found there for the Dutch East India company. He gives a very thorough description of the fruit, comparing it to

a Gourd, or an oblong sack, about two spans or a small ell long [about 32 inches], and as thick as a man's thigh, sometimes they are so large and heavy that a man can barely lift one up; covered on the outside with thick and coarse bark, garnished with angular checks and spikes, like polished diamonds, coming to short tips which do not hurt, however, even though they might seem prickly; its color is a yellowish green, and it is covered with a sticky milk, which gives it dirty or smoke-colored spots; a thick staff or stem goes through the center, around which the kernels hang, surrounded by a white, tough, and slimy flesh, which is what one eats from these fruits: the kernels are like large acorns, of which there are eighty, a hundred, or more around the aforementioned stem, and the more flesh they have around them, the better the fruit is said to be; these fleshy kernels or knobs are oblong, roundish towards the bark, but more pointed towards the stem, where it is also fastened, and lie in drawers made from the same tough substance, and are fastened to the bark6

Describing the flavor, Dampier simply says "the Jack is a very pleasant Fruit"7. Lémery advises that it has "a pleasant taste... and similar to that of a good melon"8. However, he adds that the kernels are sour and earthy tasting. Rumphius is more circumspect about the flavor, but colorfully descriptive. "[T]he taste is difficult to describe, for it seems like a mixture of honey-grapes and Oranges, but much stronger than these, smelling also like rotten apples; it is difficult to hide this fruit in one's house, for its smell will betray it"9.

Dampier's only comment on the preparation of jackfruit is that "the Stones or Kernels are good roasted."10 Rumphius gives a description of how the raw fruit is to be eaten. "The ripe Jackfruits are usually cut through lengthwise, and the slippery kernels or knobs are torn off the central stem by hand, so that one can eat the surrounding flesh by sucking it off"11.

Of the humoral properties, Rumphius says "the nature of the fruit is moist, with little heat"12.

Papaya and Jackfruit (center), from Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica

de las Yslas Filipinas, 1734

Since he does not suggest they are cooling, moisture appears to be its primary humoral property. He adds that the fruit is difficult to digest, "which is why one should not eat it on an empty stomach: for otherwise it will change into a bilious and phlegmatic humour [the bodily humor yellow bile], which usually results in the Cholera"13.

Lémery identifies the jackfruit's medicinal properties as astringent, "but of hard digestion". If eaten before they are ripe, he says they will cause "a lot of wind". On the positive side, he notes that jackfruit are "suitable for stopping sour stomachs: being cooked, they excite the semen."14 Although Rumphius said they were difficult to digest, he also gives them a boost, noting that they are not as bad as that of durians, and "are reasonably pleasant, and healthy on hot days to refresh the stomach"15.

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 431 & 468; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V2, 1712, p. 15; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 311; Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 124 & 181; Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 40, 56, 72 & 98; 2 Barlow, pp. 432 & 468; 3 Dampier, 1699, p. 320; 4 Dampier, A Continuation..., p. 98; 5 Louis Lémery, Dictionaire ou Traité Universel des Drogues Simples, 1617, translated by the author, p. 272; 6 Georgius Everhardus Rumphius, The Ambonese Herbal, E. M. Beekman, Ed, Vol1, 2011, p. 343; 7 Dampier, 1699, p. 320; 8 Lémery, p. 272; 9 Rumphius, p. 343; 10 Dampier, 1699, p. 320; 11, 12,13 Rumphius, p. 344; 14 Lémery, p. 272; 15 Rumphius, p. 344-5

Lemon

(Citrus limon)

Called by Sailors: Limon, Lemmons, Lemon

Appears: 42 Times, in 29 Unique Ship Journeys from 17 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Alicante, Cadiz & Rota, Spain; Sardinia, Italy; Tenerife, Canary Islands; Santiago, Cape Verde Islands; Jamestown, St. Helena; Cape Corso Castle & Cape of Good Hope, Africa; Qeshm Island, Iran; Basra, Iraq; Surat, India; Aden & Mocha, Yemen; Kupang, Timor; Palau Sabuda, West Papua; Côn Sơn Island, Vietnam; Java & Siumpu Island, Indonesia; Guam; Barbados, Madeira, Portugal; Chepillo Island, Costa Rica

Lemons are among the most often-mentioned fruit in the sailor's accounts from the period. This is largely due to the journal kept by Edward Barlow which mentions them eleven times during nine separate journeys. Yet, in all those citations, he has little to say about them. This is probably because lemons were very familiar to sailors.

Sailor Francis Rogers talked a bit about those he found when the Arabia

Artist: Alexander Coosemans

Still Life of Fruit and Oysters (Second Half of the 17th century)

merchant ship stopped at St. Helena in 1703. He mentioned that "the lemons are very large and fine"2. When Barlow was prisoner aboard the Dutch India merchant Burff van Liden, they made landfall at the Cape of Good Hope on the southern tip of Africa in 1674. He says, "some few lemons grow here which have been brought from the island of St. Helena", but also says that they are only there for the use of Dutch merchants.3 While at Fort Concordia on Kupang, Timor-Leste during an exploratory voyage aboard the Roebuck, William Dampier simply noted that the lemons there were 'sweet'.4 The one pirate-related account which included lemons is from a list of items John Gow's pirates found when they stopped near Cape Finisterre in Gallica, Spain.5

None of the sailors have anything to say about eating or preparing lemons. Perhaps it is as physician William Hughes puts it, "To write any thing of the description, use, or vertues of this Tree or Fruit, were but lost labor, and to no purpose"6, because it was so familiar to the readers. Most sailors, including pirates, would likely have encountered lemons while drinking punch; the second most often mentioned alcoholic beverage in the golden age pirate sailor's accounts.

Fortunately the botanists and physicians have some suggestions about how lemons should be consumed, even if they don't mention their flavor. (Hint: acidic and tart.) Louis Lémery recommends only eating large, ripe lemons "of an aromatick and pungent smell and taste: They must not be be eaten when fresh gathered from the Tree, but you ought to tarry for some time: The best are those that come from hot Countries."7 Botanist John Gerard mentions that, mixed with sugar, lemon juice is pleasant in taste.8 Hans Sloane says, "Slices of it strung so as not to touch one another, dryed and powder'd, make a sarbet and good Drink, if mix'd with Water"9. (You probably thought powdered lemonade was a modern invention.)

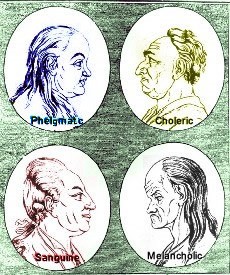

Humorally,

Four Humoral Temperaments, From

Physiognomische Fagmente jc Lavaters (1792)

John Gerard separates lemons into different parts. He says that lemon rinds (as well as those of citrons and oranges) are "sweet of smell, bitter, hot and dry." The white pulp is cold. The non-white part of the fruit is sour, "cold and dry with the thinnesse of parts." The seeds are hot and dry, because they are bitter tasting.10 Lémery agrees, stating that the rind of the lemon is hot and one the juice is cold. He also says lemon juice is good in hot weather for young bilious people.11 Bilious here refers to bile. Black and yellow bile are two of the four bodily humors; people with an excess of an excess of black bile were considered to be melancholic, while this with an excess of yellow bile were choleric.

Medicinally, Lémery says a lemon helps digestion, resists poison, fortifies the heart and brain, "allways the over-violent motion of the [humor] Blood, and of other Humours, and is good for feverish Persons.12 Gerard says that lemons comfort a cold stomach, although because the white part of the fruit is difficult to concoct (transform into a useful bodily humor), it "engendreth a grosse, colde and phlegematicke juice". He also mentions that lemon juice becomes "more nourishing, and lesse apt to obstruction and binding or stopping [the digestion]" by adding sugar to it.13

Lemons were also recognized as one of the several things that could cure scurvy. Writing in the 1630, navy sailor Nathaniel Boteler mentions in his apparent briefing to the Admiralty that "oranges, lemons, limes, pines [pineapples]; which are excellent against the scorbute"14. Talking about curing scurvy in 1639, sea surgeon John Woodall explained that "the Chirurgion or his Mate must not faile to perswaide the Governour or Purser in all places where they touch in the Indies and may have it, to provide themselves of juice of Oranges, limes, or lemons, & at Banthame of Tamarinds"15. Navy sea surgeon John Moyle advised that "where ...Fruits as Lemmons and Oranges, are freely taken, and good wine drank; there's no fear of the scurvy, for they attenuate the Blood, and open Obstructions, and prevent that Distemper."16

1John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 26; John Baltharpe, The straights voyage or St Davids Poem, 1671, p. 64; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 58, 69, 81, 86, 163, 186, 239, 270, 283, 312, 480-1; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V1, 1712, p. 26; Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea..., V2, 1712, p. 15, 43 & 93; John Covel, Diary, Early Voyages in the Levant, Thomas Dallam, ed., 1893, p. 120; William Ambrose Cowley, "Cowley's Voyage Round the World", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 16 & 25; William William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 10 & 33; Dampier, A Continuation of a New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1709, p. 56 & 72; Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 162; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 12, 22 & 186; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 5 & 286-7; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 29, 381 & 438-9; Raveneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 330; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 158-9, 178, 191 & 233; Bartholomew Sharp, "Captain Sharp's Journal of His Expedition", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 33; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 54; Henry Teonge, The Diary of HenryTeonge, 1825, p. 268; Nathaniel Uring, The Voyages and Travels of Captain Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 106; 2 Ingram/Rogers, p. 191; 3 Barlow, p. 239; 4 Dampier, A Continuation..., p. 56; 5 Ed Fox, “33. James Williams, from The Examination of James Williams, 27 March, 1725. HCA 1/55 ff. 103-104”, Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 162; 6 William Hughes, The American physitian, 1672, p. 47-8; 7 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 36; 8 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie fof Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1463; 9 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, 1707, p. 178; 10 Gerard, p. 1463; 11,12 Lémery, p. 36; 13 Gerard, p. 1465; 14 Nathaniel Boteler, Boteler's Dialogues, 1929, p. 66; 15 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1639, p. 164; 16 John Moyle, Chirurgus marinus, or The sea chirurgion, 1693, p. 181;

Lime