Fruit in Sailor's Accounts Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 <<First

Fruit in Sailors Accounts During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 7

Fruit Found In A Single Sailor's Account

Photo: Forest and Kim Starr - Cocoplum, Chrysobalanus icaco

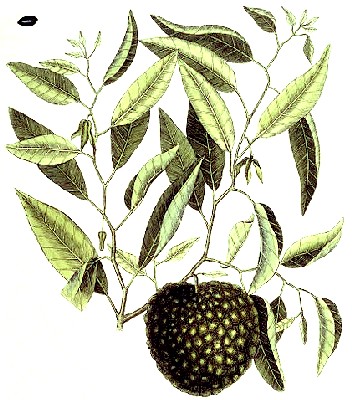

Cocoplum

(Chrysobalanus icaco)

Called: Coco-plum, Coco-plumb

Appears: 3 Times, in 2 Unique Ship Journeys.1

In Author: William Dampier

Type of Ship: Buccaneer

Locations Where Found: St. Vincent; Isla Buey, Mexico; Salvador, Brazil

Cocoplums would seem to be an excellent fruit for sailors, given that one type of this plant grows near the coast and is salt-tolerant. This type would have been fairly easy for them to access, when in tropical locations such the Caribbean, Central America, northwestern South America and tropical western Africa. In addition, it can bear fruit year round in warm locations.2 Despite all these things, it is only found in William Dampier's books.

Dampier found cocoplums in several locations in the New World. During his tenure as a logwood cutter in 1676, he described them as "about the bigness of a Horse-Plum [American plum], but round; some are black, some white, others redish: The Skin of the Plum is very thin and smooth; the inside white, soft and woolly" 3. Mathematician John Taylor found them while in Jamaica in 1687, although he only mentioned that they could be found "growing together in large clusters."4 Physician John Parkinson adds a bit of detail, explaining that cocoplums are

Photos: Filo gèn & Hans Hillawaert - Pink and Reddish Cocoplums, Chrysobalanus icaco

as great as a small Apple, and like unto a Plum, that is, somewhat long, greene before it is ripe, and yellowish after, (yet [Caroli] Clusius saith he received one from Doctor Tovay out of Spaine, that was blackish, light and shrunke which he imputeth to the unripenesse of it) some having a reddish pulpe within, and some a white... divided as it were into four parts, in each whereof lye many small grains or hard white kernells.5

Of the flavor of cocoplums, Dampier says, "I have tasted some that have been saltish; but they are commonly sweet and pleasant enough, and accounted very wholsom." He also says, that they are "rather fit to suck than bite".6 Parkinson simply notes that they are "very sweet and delicate in taste"7.

Being a physician, Parkinson notes that medicinally the fruit "hath an astringent power therein to stay laskes [diarrheas], especially if they be eaten while they are greene and not ripe."8 He doesn't mention anything about their humoral properties.

1 William Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 48-9; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 51; 2 Stephen H. Brown, "Chrysobalanus icaco", University of Florida IFAS Extension, gathered 6/28/22; 3 Dampier, 1700, Part 2, p. 49; 4 John Taylor, Jamaica in 1687, David Buisseret ed, 2010, p. 198; 5 John Parkinson, Theatrum Botanicum, 1640, p. 1634; 6 Dampier, 1700, Part 2, p. 49; 7,8 Parkinson, p. 1634

Photo: Wiki User Ji-Elle - Colocynth Fruit and Seeds, Citrullus colocynthis

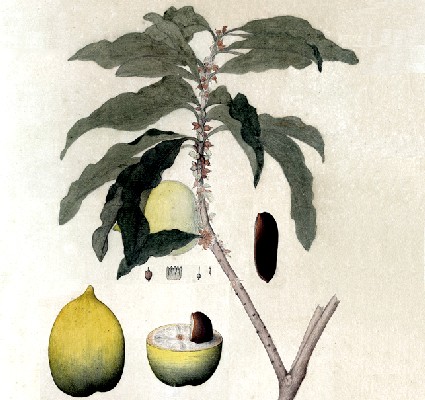

Colocynth

(Citrullus colocynthis)

Called by Sailors: Coloquintida

Appears: 1 Time, in 1 Unique Ship Journeys.1

In Author: John Atkins

Type of Ship: Navy

Location Where Found: Barbados

Colocynth only appears in sea surgeon John Atkins' account, and he only lists it among other fruits he found in Barbados. They look remarkably like small watermelons, even growing on vines. Herbalist John Gerard describes them as "a kind of the wilde Gourd, it lieth along creeping on the ground as do the Cucumbers and Melons... the fruit [is as] round as a bowle, covered with a thin rinde, of a yellow colour when it is ripe... the white pulpe or spungie substance appeareth full of seeds.... [it] is most extreame bitter"2. It is readily apparent why only one sailor saw fit to include it in their list of discovered edible plants.

Medicinal uses are probably the reason Atkins mentioned colocynths in his account. Gerard says the humorally a colocynth is "in all his parts bitter, so it is likewise hot and drie

Photo: H. Zell - Colocynth Fruit, Citrullus colocynthis

in the later end of the second degree; and therefore it purgeth, clenseth,openeth and perforrneth all those things that most bitter things do". Purging was an important part of cleansing the body of unwanted humors. Gerard goes on to explain that it operates "so violently, that it doth not onely draw forth fleagme [phlegm, a humor]

and choler [another humor, yellow bile] marvellous speedily, and in very great quantitie: but oftentimes fetcheth forth bloud [a third humor]

and bloudy excrements, by shaving the guts, and opening the ends of the meseraicall veines [mesenteric vein - a vein in the abdominal cavity.]"3

In line with Gerard's description, physician Hans Sloane says that medicinally, "This is counted an extraordinary Medicine against the Belly-ach They take a handful of the Leaves, boil them in water, and give the Decoction, which usually Vomits and Purges, but more certainly the first."4 He says it also can be used against dropsy (edema) and in clysters or enemas for the same reason. Citrullus seeds are among the medicines included in some of the sea surgeon's chests.

1 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 217; 2 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 914; 3 Gerard, p. 915; 4 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 1, 1707, p. 228

Photo: T. G. Lideep - Custard Apple Fruit (Annona squamosa)

Custard Apple

(Annona reticulata)

Called: Custard-Apple

Appears: 2 Times, in 2 Unique Ship Journeys.1

In Author: William Dampier

Type of Ship: Buccaneer/Explorer

Locations Where Found: Santiago, Cape Verde Islands; Salvador, Brazil

Dampier talks about custard apples during his visit to the Cape Verde Islands as well as on the coast of Brazil on the way to explore Australia in his ship Roebuck. Physician Hans Sloane says they are found "in the Plains or Savanna's every where, if planted, in Jamaica and the Caribes."2 Both historian John Oldmixon and sugar plantation owner Richard Ligon mention finding them in Barbados.3 Dampier notes, "I have seen of them (tho' I omitted the Description of them before) all over the West-Indies, both [on the] Continent and Islands; as also in Brazil, and in the East-Indies."4

Dampier described the fruit being "as big as a Pomegranate, and much of the same colour.

Photo: N Aditya Madhav -

Custard Apple Fruit on Tree (Annona squamosa)

The out-side Husk, Shell or Rind, is for substance and thickness between the Shell of a Pomegranate, and the Peel of a Sevil-Orange; softer than this, yet more brittle than that. The Coat or Covering is also remarkable in that it is beset round with small regular Knobs or Risings; and the inside of the Fruit is full of a white soft Pulp"5. Sloane says custard apples are "of a deep yellow or Orange Colour, when ripe, the Membrane covering it has many Lines, rais'd and depress'd in it, making its Surface divided into many Areae"6. Ligon says it is as big as a large apple and the color of a Warden pear.7

The inside of a custard apple contains large, dark-brown seeds as seen above. "It has in the middle a few small black Stones or Kernels; but no Core, for ‘tis all Pulp."8 Sloane notes that "the Seeds are black, oblong, depress'd, and shining, like those of the Sowr-sop only much smaller and blacker"9. Ligon says approvingly, "Many seeds there are in it, but so smooth, as you may put them out of your mouth with some pleasure."10 Perhaps it would have been even better than spitting watermelon seeds.

Dampier suggests that the custard apple was named such because it was thought to taste like custard. He says the pulp "sweet and very pleasant, and most resembling a Custard of any thing, both in Colour and Tast"11. Sloane agrees, listing the same basic reasons and later adding, "It is thought a very delicious Fruit."12 In a letter written in 1683 by Captain John Poyntz about the island of Tobago, Poyntz enthused, "The custard-apple to my taste I must confess is very delightful."13

Artist: Mark Catesby -

Custard Apple and Tree (1731)

Ligon gives an interesting description of how custard apples were eaten on Barbados when he was there.

When 'tis ripe, we gather it, and keep it one day, and then it is fit to be eaten. We cut a hole at the lesser end, (that it may stand the firmer in the dish) so big, as that a spoon may go in with ease, and with the spoon eat it. Never was excellent Custard more like itself, than this to it; only this addition, which makes it transcend all Custards that art can make, though of natural ingredients; and that is, a fruity taste, which makes it strange and admirable.14

The method he describes is so detailed that he must have eaten at least one this way. However, Oldmixon, who criticizes Ligon several times in his book, says, "Ligon's Description... is not always to be depended on: For ...the Fruit is so ordinary, that none but the Servants and Negroes eat it."15 Oldmixon was writing about sixty years after Ligon according to his own account16 and it is possible that tastes and habits had changed during that period.

Physician Sloane is the only one to comment on the health qualities of custard apples, not giving his own opinion, but relying on those of other authors. Citing French botanist Jean-Baptiste du Tertre, Sloane says were humorally dry and hot. French pastor Chares de Rochefort said they rid the Stomach of 'tough Humours'. Medicinally, Sloane cites both John de Laet and botanist Paul Hermann who suggest the fruit caused wind in the intestines, although the seeds stopped diarrhea. He says du Tertre found the fruit "spoils the Liver, causing Inflammations and Heats in the Face."17

1 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 33 & 66; 2 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, 1707, p. 167; 3 John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, 1708, p. 95 & Richard Ligon, A True And Exact History Of the Island of Barbadoes, 1673, p. 71; 4 Dampier, Part I, 1703, p. 34; 5 Dampier, Part I, 1703, p. 33; 6 Sloane, p. 167; 7 Ligon, p. 72; 8 Dampier, Part I, 1703, p. 33-4; 9 Sloane, p. 167; 10 Ligon, p. 72; 11 Dampier, Part I, 1703, p. 34; 12 Sloane, p. 167; 13 The Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure, John Hinton, ed., 1749. p. 156; 14 Ligon, p. 72; 15 Oldmixon, p. 95; 16 Oldmixon, p. 17; 17 Sloane, p. 168

Photo: Alex Popovkin - Genipa Americana, Bahia, Brazil

Genipa

(Genipa)

Called: Jennipah

Appears: 1 Time, in 1 Unique Ship Journey.1

In Author: William Dampier

Type of Ship: Buccaneer/Explorer

Location Where Found: Salvador, Brazil

Genipas are mentioned only by Dampier, who found them in Brazil. He mentions that the logwood cutters used the wood of the genipa tree to make axe handles when he was living at the Bay of Campeche in southern Mexico, so he must have seen them when he was there as well. Genipas are native to tropical locations in the Americas in Florida, the Caribbean, Mexico and various countries in South America2, so it is surprising that none of the various sailors who visited the New World mention them. Curious also is that none of the books by English physicians and botanists discuss this fruit. Other than Dampier, the primary source for information on genipas come from French authors such as chemist Nicolas Lémery, pastor Charles de Rochefort and botanist and priest Jean-Baptiste du Tertre.

Dampier says the genipa is "a sort of Fruit of the Calabash or Gourd-kind.

![]()

Artist: Johann Wilhelm Weinmann

Genipa Plant, From Phytanthoza Iconographia (1735-45)

It is about the bigness of a Duck-Egg, and somewhat of an Oval Shape; and is of a grey Colour. The Shell is not altogether so thick nor hard as a Calabash: 'Tis full of whitish Pulp mixt with small flat Seeds"3. du Tertre compares its size to a goose egg, adding that the fruit contains "fairly firm flesh molasses in the middle, & is filled with infinite number of flat seeds."4 Charles de Rochefort suggests the fruit is the size of an ordinary apple, not giving any further description.5 Lémery describes it as being "larger than an orange, round, covered with a tender, ash-colored bark; Its flesh is solid, yellowish, viscous, filled with a pleasant juice with a pleasant odor: there is in the middle of this fruit a cavity filled with seeds compressed, flat, almost orbular, surrounded by a soft pulp"6.

du Tertre has more to say about the effects of the 'mollasses' found in the center of genipas. "The juice that is drawn from this fruit dyes the hands, & everything it touches with a black color, which can only be erased nine days later. Malicious inhabitants usually catch newly come girls and women, making them believe that this juice is used to embellish the hands & face & I married one who had her hands & face black."7 Both he and de Rochefort also talk about the curious way the fruit ripens and distributes its seeds. "Falling from the Tree they make a noise like that of a gun discharg'd: which proceeds hence, that certain winds or spirits pent up in the thin pellicles which enclose the seed, being stirr'd by the fall, force their way out with a certain violence."8

There are two opinions on the taste of genipas. Dampier suggests "It is of a sharp and pleasing Taste, and is very innocent."9 However, du Tertre says, "This fruit has a good smell, a sour taste"10. The other two authors who talk about it do not discuss the flavor. de Rochefort mentions in passing that they are sour.11 Modern botanist Julia F. Morton says that "the flavor, acid to subacid, resembles that of dried apples or quinces."12 The difference in opinion on the flavor among the period authors appears to reflect their enjoyment of the acidic tang.

Photo: Alex Popovkin -

Genipa Americana, Bahia, Brazil

The fruit is eaten after it is ripe13. Lémery explains this as: "it becomes soft while dying... & then it is good to eat."14 de Rochefort says once a genipa is ripe it "seems to have been baked in an Oven"15. Dampier says that to eat the raw fruit, "both Pulp and Seeds must be taken in to the Mouth, where sucking out the Pulp you spit out Seeds."16

No one mentions the humoral qualities of the fruit, although some do discuss the medicinal properties of genipas. de Rochefort says when "eaten without taking away the little skin within them, are extreamly binding"17. This would make them effective against diarrheas or fluxes. Lémery similarly suggests it "esteemed astringent [contracting] & cleansing against the loose stomach"18, which agrees with de Rochefort's statement. Both indicate that the fruit quenches thirst, which de Rochefort attributes to its sour flavor.

Lémery also says that unripe genipas are used to make medicines including "in poultices, in ointments for [treating] malignant ulcers." He adds, "We draw from this fruit by expression a type of wine, or vineyard liquor which when it is recent appears astringent & refreshing", although he says it loses those qualities as it ages.19

1 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 67; 2 Rudolf Mansfield, Mansfield's Encyclopedia of Agricultural and Horitcultrual Crops, 2001, p. 1775; 3 Dampier, p. 68; 4 Jean-Baptiste du Tertre, Histoire generale des Antilles habitées par les François, Tome II, translated by the author, 1647, p. 190; 5 Charles de Rochefort, The History of the Caribby Islands, 1666, p. 31; 6 Nicolas Lémery, Traité universel des drogues simples, translated by the author, 1617, p. 275;7 du Tertre, p. 191; 8 de Rochefort, p. 31; 9 Dampier, p. 68; 10 du Tertre, p. 191; 11 de Rochefort, p. 31; 12,13 Julia F. Morton, Fruits of warm climates. 1987, p. 441; 14 Lémery, p. 275; 15 de Rochefort, p. 31; 16 Dampier, p. 68; 17 de Rochefort, p. 31; 18,19 Lémery, p. 275

Photo: Wikimedia User OtterAM - Chilean Lucumas

Lucuma

(Pouteria lucuma)

Called by Sailors: Lucumo

Appears: 2 Times, in 2 Unique Ship Journeys.1

In Author: Amedee-Francois Frezier

Type of Ship: Merchant

Locations Where Found: Coquimbo & Hiloe, Chile

Lucumas appear only in French engineer Amedee-Francois Frezier's account of the time he spent in South America, spying on the Spanish between 1712 and 1714. None of the English buccaneer or privateer voyages which prowled along the coasts of South America during this period mention this fruit. This is likely because the it grows at elevations of 9,000 and 10,000 feet, which is hardly the sort of place sailors covertly stopping on enemy shores would have gone . It is found in the highlands of western Chile and Peru, possibly southeastern Ecuador and, to a limited extent, in Bolivia.

Photo: Wikimedia User JudgeFloro - Lucuma Fruit in Tree, Philippines

It is particularly popular in central Chile.2 Frenchman Frezier, an (alleged) ally of the Spanish, would have had access to such locations.

Fortunately, Frezier was a keen observer and he provides a fairly good description of the tree and its fruit when the merchant vessel St. Joseph reach Coquimbo, Chile in May of 1713.

In this Climate we begin to see a Tree, which does not grow in any other Part of Chili, and is peculiar to Peru; it is call'd Lucumo [Pouteria lucuma]; The Leaf of it somewhat resembles that of the Orange-Tree and the Floripondio [Brugmansia arborea or angel's trumpet]; the Fruit is also very like a Pear, which contains the Seed of the latter; when ripe, the Rind is a little yellowish, and the Flesh of it very yellow, almost of the Taste and Consistence of a new-made Cheese: In the midst of it is a Kernel, exactly like a Chestnut in Colour, Hairiness and Substance, but bitter, and good for nothing.3

Writing eleven years later, explorer and botanist Louis Feuillée says that Frezier's description contained several

Artist: Joaquim José Codina - Lucuma caimito de Bresil (c. 1790)

minor errors. Among them are that the fruit doesn't resemble a Floripondio pear because it's rounder, its' skin is more dirty white than yellow when ripe and it can contain two or three pits rather than just one.4 Regarding the taste, modern authors say that although it is initially has a good flavor when eaten raw, it has a 'peculiar' aftertaste that ultimately makes it less appealing.5

Just as none of the English sailors talk about lucumas, none of the English botanists or physicians from this period discuss it. This is probably because they were unaware of it. Feuillée, who explored Chile in 1707-8, mentions that while there, "the fruit [was given] to eat to the sick, because there is nothing bad or unhealthy in it."6 He doesn't provide any information about its medicinal properties, however.

Sixteenth century Spanish physician Nicolás Monardes mentions a 'leucoma' fruit in his work on medicines found in the new world. He describes it as being like a chestnut, so if it was from a lucuma, it was only the pit. Given that Monardes never left Spain and described American plants from what was brought to him at Seville, it makes sense that the only part he saw was the pit because the fruit probably wouldn't have lasted the length of a journey from South America to Spain. He suggests the pit is "good for the laske [looseness of the bowels], because it is very dry: they say it is a temperate [probably meaning 'humorally balanced'] fruite."7

1 Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 136 & 172; 2 Julia F. Morton, Fruits of warm climates. 1987, p. 405; 3 Frezier, p. 136; 4 Louis Feuillée, Journal des observations physiques, mathetiques et botaniques, 1725, translated by the author, p. xiv-xv; 5 Morton, p. 406; 6 Feuillée, p. 34; 7 Nicolás Monardes, Ioyfull newes out of the newfound world, Translated by John Frampton, 1577, not paginated

Photos: John Rusk and Wiki User Syrio

Comparison of Manzanita (Arctostaphylos canescens) and English Ivy (Hedera helix) Berry

Manzanita

(Arctostaphylos)

Called by Sailors: Manzita

Appears: 1 Time, in 1 Unique Ship Journeys.1

In Author: Edward Cooke

Type of Ship: Privateer

Location Where Found: Cabo San Lucas, Mexico

No sailor actually mentions manzanitas by name during this period. Their identification is an educated guess based on the description of a berry Edward Cooke found in Cabo San Lucas during Woodes Rogers' privateer voyage. As he explains, Cooke saw "a Sort of round Berries the Natives gather off the Trees, in Bigness and Shape resembling our Ivy-Berries. These they dry at the Fire; and when bit[ten], the Skin peels off, and the Inside looks and eats somewhat like our parch’d Pease."2. Manzanita is the Spanish word for 'little apples', probably in part because of their coloring and shape.

There is no mention of this fruit in the period physician's or botanist's books, probably because most of the English books dealing with plants from this period focus on the

Photo: Thomas Meehan

Manzanita or Bear-berry, Arctostaphylos uva-ursi, From

The Native Flowers and Ferns of the United States (1878)

Caribbean and the eastern coast of North America. Given the location where these trees grow, it would have been the Spanish who had the most experience with them, along with any of the buccaneers or privateers who ventured to the western side of the Americas. "California is manzanita central. All but three of the ninety species found in the wild are endemic to California; a few species are found north into Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia, east to the Rocky Mountains, in the non-desert parts of Nevada, Arizona, and Texas, and south into Central America."3

In support of Cooke's claim that the natives supplied them to the Rogers' crew, modern historian Virgil J. Vogel explains that manzanita berries were "widely used as food, fresh or cooked, by western Indians."4. They were harvested when they turned red by beating the shrub causing the berries to fall into waiting baskets. In addition to being consumed raw or cooked, they were also crushed to be made into beverages and jellies.5

Although there are no English medicinal notes for these plants, the Native Americans on the western side of the North America used them medicinally in ways most English physicians would have readily understood. Vogel explains, "The Miwok [tribe] chewed the leaves for stomachache and cramps. ...Some tribes crushed the astringent leaves for a remedy for bronchitis and dropsy [edema]. A tea made from the berries was used as a wash for poison oak infection. The Atsugewi used a decoction of the leaves on cuts and burns."6

1,2 Edward Cooke, Voyage to the South Seas, V. 1, 1712, p. 338; 3 Paula Panich, "Manzanita", PacificHorticulture.org, gathered 6/30/22; 4 Virgil J. Vogel, "American Indian Foods as Medicine", American Folk Medicine: A Symposium Wayland D. Hand, ed., 1980, p. 134; 5 "Manzanita (Arctostaphylos)", Plants of California, website, gathered from archive.org, 6/30/22; 6 Vogel, p. 134-5

Photo: flickr User travel_oriented - Sliced Nectarine

Nectarine

(Prunus persica)

Called by Sailors: Nectarine

Appears: 1 Time, in 1 Unique Ship Journey.1

In Author: Alexander Hamilton

Type of Ship: Merchant

Location Where Found: Basra, Iraq

Nectarines grew in Europe during this period, so they would have been familiar to the English audience. They are listed in Alexander Hamilton's account of the East Indies, although he doesn't have anything to say about them. Botanical authors considered nectarines to be a type of peach2, which they are. They have "a genetic mutation that gives them smooth skin rather than the characteristic fuzzy skin of peaches. Otherwise, they’re nearly identical from a genetic perspective."3 This may explain why they do not appear in sailor's accounts as often as peaches.

In general terms, botanist John Parkinson is the only author under study to treat them separately from peaches. He notes that nectarines are "smaller, rounder, and smoother then Peaches, without any cleft on the side, and Without any douny cotton or freeze at all"4. Inside, one finds "a fast and firme meate... with a rugged stone within it, and a bitter kernell."5 (These comments are also summarized by fellow botanist John Gerard in his discussion of peaches; which he admits he got from Parkinson.6)

Parkinson goes on to identify six different types of nectarines, indicating that some of them might

Photo: Richard Parker - Nectarines of Varying Colors

actually be the same type of fruit. They are differentiated primarily by color. His six nectarines include: the 'Muske', 'Romane red', 'bastard red', yellow, 'greene' and white nectarines. The only one not described by color was the musk, which he explained, is "the best [of the] red Nectorins... some thinke that this and the next Romane Nectorin are all one." He describes the red roman nectarine as "reddish at the bottome on the outside, and greenish within:, the bastard red was "neither so large nor open as the former [red roman], and yellowish within at the bottome: the fruit is red on the outside". He doesn't describe the greene or yellow nectarine, although their names are suggestive. The white he says is "more white on the outside when it is ripe, then either the yellow or greene"7.

Of the flavor of nectarines, Parkinson says it has a "very delicate in taste, especially the best kindes". He adds, "The fruit is more firme then the Peach, and more delectable in taste; and is therefore of more esteeme, and that worthily." He also talks about the flavors of some of the individual types of nectarines. The musk, he says, "both smelleth and eateth as if the fruit were steeped in Muske", while the roman red "of an excellent good taste."The bastard red "is a good fruit, but eateth a little more rawish then the other, even when it is full ripe." The better yellow fruit is "an excellent fruit, mellow, and of a very good relish". However, the green nectarine is "accounted with most to be the best rellished Nectorin of all others."t8

Medicinally, they have the same properties as peaches (for more, see the peach entry here). Merchant John Fryer mentions some medicinal properties for nectarines, peaches and apricots not found in the peach entry. He says those he found in Goa, India in the late seventeenth century were believed to "cleanse the Blood, and Salivate to the height of Mercurial Arcanaes; and afterwards fatten as much as Antimony"9.

1,2 Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 78; 2 John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris, 1904, p. 582; 3 "What’s the Difference Between Peaches and Nectarines?", Healthline.com, gathered 7/1/22; 4 Parkinson, p. 582; 5 Parkinson, p. 583; 6 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 1446; 7,8 Parkinson, p. 583; 9 John Fryer, A New Account of East India and Persia, 1698, p. 182;

Photo: Jim Conrad

Ripe Macaw Palm Berries (Conrad Calls Them Coyal Nuts)

Palm Berry

(Acrocomia aculeata)

Called by Sailors: Dendees, Macaw Berries, Palm-Berries

Appears: 2 Times, in 2 Unique Ship Journeys.1

In Author: William Dampier

Type of Ship: Buccaneer/Explorer

Location Where Found: Panama; Salvador, Brazil

William Dampier said that palm berries "grow plentifully about Bahia [Salvador, Bahia, Brazil]" in 1699.2 Dampier gave the ones he found in Panama a different name, explaining, "we got Macaw berries in this place, wherewith we satisfied ourselves this day"3. Physician Hans Sloane indicated the source of Dampier's 'Maccaw Berries' was the plant Palma Spinosa Minor (or, the Macaw Palm) in his book.4 This plant is today classified as the Acrocomia aculeata.

About palm berries,

Photo: Jose Reynaldo da Fonseca - Macaw Palm Berries on Tree (Acrocomia Aculeata)

Dampier says "the largest are as big as Wall-nuts; they grow in bunches on the top of the Body of the Tree, among the Roots of the Branches or Leaves, as all Fruits of the Palm kind do."5 English botanist Philip Miller wrote, "The fruit is about the size of a middling Apple, and is inclosed in a very hard shell."6

To prepare the fruit, Dampier was told to roast them, "but when I had one roasted to prove it, I did not like it."7 Of the berries he had earlier found in Panama, he said they were edible, but coarse fare.8 Botanist Miller suggests that the way to eat the fruit was to "pierce the tender fruit, from whence flows out a pleasant liquor."9 Modern naturalist Jim Conrad reports that such palm fruits are initially, "softer inside. You put sugar on the nuts and they're good to suck on when they are younger."10 This may explain why Dampier had so much trouble with them.

Photo: Peter Deplewski - Inside of a Macaw Palm Berry

Neither Dampier nor Sloane talk about the health properties of palm berries. Miller appears to have had no interest in this aspect. In asking locals in Brazil about this, Jim Conrad reported a rather interesting conversation about their potential use in healing.

"Boil some leaves in water and make a tea," a young man told me. "It's good for bones, makes them strong, and keeps your joints in good shape."

"Nah, no good at that," an old man with bad arthritis contradicted in this traditional society where people seldom openly contradict one another.

"Well, if your bones and joints are in good shape," the young man compromised, "a tea of Coyol [tropical palm] leaves keeps them that way.

The old man looked skeptical but didn't say a word.11

1 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 20; Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 71; 3 Dampier, 1699, p. 20; 4 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, 1707, p. 120; 5 Dampier, 1703, p. 71; 6 Philip Miller, "Palm", The gardeners dictionary, 1768, not paginated; 7 Dampier, 1703, p. 71; 8 Dampier, 1699, p. 20; 9 Miller, not paginated; 10,11 Jim Conrad, "Jim Conrad's Naturalist Newsletter", www.backyardnature.net, gathered 4/29/22;

Artist: Juan Sanchez Cotan - Pepino Melon (c. 1602)

Pepino

(Solanum muricatum)

Called by Sailors: Pepino, Pepo

Appears: 1 Time, in 1 Unique Ship Journey.1

In Author: Amedee-Francois Frezier

Type of Ship: Merchant

Location Where Found: Isla del Carmen, Mexico; Panama

Pepinos look remarkably like striped melons, but they aren't melons nor are they related to them. They are part of the nightshade family, related to both tomato and eggplant fruits. (Yes, eggplants are technically a fruit.) They originated in South America, where they are called pepinos - the Spanish word for cucumbers - because of the resemblance of some pepino cultivars to this common fruit.2

Mathematician Amedee-Francois Frezier, who stayed with the Spanish in South America for several years, likewise suggests pepino melons are a type of cucumber. He likely comes got the name from the local Spanish territory governors with whom he

Photos: Rob Hille and Wiki User NobbiP - Different Colored Pepinos

hobnobbed. Beyond this, Frezier only gives a single sentence description of the fruit. "It is very refreshing, and has some Taste of a Melon, but [is] fady [the flavor fades]."3

They are believed to have come from Northern Ecuador/Southern Colombia.4 Unfortunately, likely due to their name, their presence only in South America at this time and their resemblance to cucumbers, they are not described as an individual fruit in the period botanical and medical texts under study. Even if they had, they would most likely have been given the properties associated with cucumbers. So we must rely on modern descriptions.

Ripe fruit are purple and either yellow or yellowish-green in color. They are quite variable in shape, with some appearing apple-shaped, others round at the bottom and pointed at the top and still others long and cucumber-shaped.5

Photo: Caroline Léna Becker - Ripe Pepino Fruit on the Shrub

The purple coloring at some times appears in stripes on the body of the fruit and at other times covers the majority of the skin. The round ones are about the size of an apple. The flesh inside is yellow, containing small yellow seeds in a membrane in the center like melons do.

Opinions of the flavor of pepinos vary. One source suggests that it has "a mild taste, very similar to cantaloupe."6 Another says a pepino is "a succulent, juicy, and sweet fruit that is used mainly in desserts, although some cultivars have been used in salads due to their higher acidity content and grassy flavor notes"7 Wikipedia says "its flavor recalls a succulent mixture of honeydew and cucumber, and thus it is also sometimes called pepino melon or melon pear."8 The fruit is usually prepared by peeling the skin off and eating the pulp inside.9

From a holistic medical perspective these fruit "are a good source of beta-carotene, vitamin C, and potassium, and are rich in dietary fiber. They are very hydrating with water making up 95% of the fruit’s content. The purple fruits contain flavonoids and phenols which provide antioxidant benefits."10

1 Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 186; 2 "Purple Pepinos", specialtyproduce.com, gathered 7/5/22; 3 Frezier, p. 186; 4 Michal Piotr Boym, Flora Sinesis, 1656, interpreted by the author, not paginated; 4 Carolina Contrerar, Mauricio Gonzalez-Aguero, and Bruno Defilippi, "A Review of Pepino (Solanum muricatum Aiton) Fruit", Horticultural Science 59(9), 2016, p. 1127; 5 Jules Janick & Robert E. Paul, The Encyclopedia of Fruits and Nuts, 2008, p. 857; 6 "Pepino", tradewindsfruit.com, gathered 7/7/22; 7 Contrerar et al., p. 1127; 8 "Solanum muricatum", wikipedia.com, gathered 7/7/22; 9 Janick & Paul, p. 857; 10 "Purple Pepinos", gathered 7/5/22

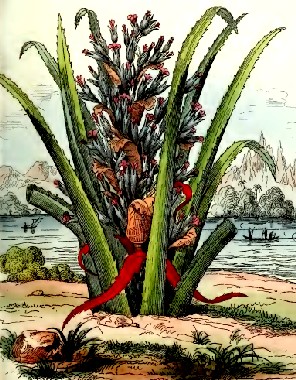

Pinguin

(Bromelia pinguin)

Called by Sailors: Penguin

Appears: 2 Times, in 2 Unique Ship Journeys.1

In Author: William Dampier

Type of Ship: Buccaneer

Location Where Found: Isla del Carmen, Mexico; Panama

While William Dampier is the only sailor under study during the period to talk about pinguin fruit as food, Captain Nathaniel Uring does mention the plant in his book. He was off the coast of Honduras in 1712 to purchase logwood when he took a canoe ashore to find food. "The Sun being set, we gather'd Wood and made a Fire, where we continued till the Morning, and then attempted to get over the Hill; but found it impossible to force a Way through the Penguins, Bryars, and other prickly Plants which grew there"2. Even today, Bromelia pinguin plants serve to protect land "It is much planted for hedges, even in regions where it is not native."3. Dampier describes the plant, "The Leaves of this Stalk are half a Foot long, and an Inch broad; the Edges full of sharp Prickles." He later adds, "They grow so plentifully in the Bay of Campeachy, that there is not passing for their high prickly Leaves."4

In addition to Mexico and Panama, physician Hans Sloane says that they grow "very

Artist: Félix-Edouard Guerin

The 'Red Pinguin' Plant (Called 'Ananas Sauvage' by Guerin),

From Dictionnaire Pittoresque d'Histoire Naturelle, Vol. 1 (1833)

plentifully in the Caribes, and Jamaica, between Passage Fort [Portmere] and the Town [either referring Kingston or Port Royal], as likewise towards the Sea-side by the Salt Ponds."5

Dampier describes two different pinguin fruits: one colored red and the other yellow. He says the yellow "grows at the head of the Stalk, in two or three great clusters, 16 or 20 in a cluster. The Fruit is as big as a Pullet’s [young hen's] Egg, of a round form, and in colour yellow. It has a thick Skin or rind, and the inside is full of small black seeds, mixt among the Fruit."6 He notes that the red pinguin fruit is 'too much alike' the yellow, although it "is of the bigness and colour of a small dry Onion, and is in shape much like a Nine-pin; for it grows not on a Stalk, or Stem, as the other, but one End together as close as they can stand one by another, and all from the same Root, or cluster of Roots."7 Dutch physician Willem Piso likewise identified both red and yellow plants, noting that the red fruit was five inches long.8

Comments on the flavor are somewhat contradictory. Talking about the yellow pinguin, Sloane says, "The Fruit is very acceptable by reason of its grateful acidity, but it not only sets the Teeth speedily on edge, but likewise brings the Skin off of the Roof of the Mouth and Tongue."9 Dampier's comment on the yellow fruit is more curt and a little less drastic, but strikes a similar note. "It is sharp pleasant Fruit." However, he later adds that both the yellow and red fruits are "wholesome, and never offend the Stomach; but those that eat many, will find a heat or tickling in their Fundament [anus]."10 Writing in 1750 about plants he found on Barbados while there between 1736 and the late 1740s, Welsh naturalist and clergyman Griffith Hughes says the "eatable Part, hath some small Resemblance, in its Flavour, of the Pine[apple]"11. Dean, a modern commentator who found them in Florida, says, "The raw fruit can be extremely acidic and can burn the lip, tongue and throat. It needs to be diluted." He later explains " I know if I eat it my tongue and mouth feel fuzzy for a few hours, as if chemically shaved. But I also know people who can eat them without any oral effect."12

None of the period authors mention how the fruit is to be consumed. Hughes indicates that it can be eaten raw: "The outward Covering of this fruit ...peels off from a white pulpy Substance, wherein are innumerable

Photo: Dr. Hans Gunter-Wagner - Ripe Yellow Bromelia Pinguin Fruit on the Plant

small flattish black Seeds. This, being the eatable Part"13. Modern writer Dean reports that it "can be eaten raw or cooked and is used to make a tart"14. It seems likely that both Dampier and Sloane ate them raw given what they said about the flavor, although this is not explicitly stated.

Piso suggests the fruit is "cold and slippery", possibly suggesting humoral qualities, although the second adjective is not clear from the Latin text. He also says that it "expels by the seat [defecation] and urine all manner of gross and cold humors"15. So it apparently purged the stomach of perceived bad humors according to him.

Sloane provides some opinions about its medicinal uses. He notes, "It quenches Thirst extremely, and on the landing of the English Forces on Hispaniola, in their want of water, was thought to save many Lives by that its quality."16 He is referring to the failed English attack on Santo Domingo in late April of 1655. (The English eventually settled for taking Jamaica instead.) Both he and Hughes suggest that it is good in treating fevers, with Hughes warning "provided it be used very moderately; for by Its grateful and active Sharpness it is capable of penetrating through the most tough and tenacious Scurf, by that means uncovering the Orifices of the Salival Ducts, and enabling the Glands of the Mouth and Throat to discharge the Contents"17. Sloane also mentions that Dutch geographer Joannes de Laet said the fruit was also good against scurvy.

1 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 426 & Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 94; 2 Nathaniel Uring, The Voyages and Travels of Capt. Uring, 1928, p. 140; 3 Paul C. Stanley & Julian A. Steyermark, Flora of Guatemala, Vol 24, Part 1, 1958, p. 394; 4 Dampier, 1699, p. 263; 5 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 1, 1707, p. 248; 6,7 Dampier, 1699, p. 263; 8 Willem Piso, Historia naturalis Brasiliae, translated by the author,1648, p. 88; 9 Sloane, p. 248; 10 Dampier, 1699, p. 263; 11 Griffith Hughes, A Natural History of Barbados, 1750, p. 232; 12 Dean, "Wild Pineapple", eattheweeds.com, gathered 7/8/22; 13 Hughes, p. 232; 14 Dean, gathered 7/8/22; 15 Piso, p. 88; 16 Sloane, p. 248; 17 Hughes, p. 232

Photo: Wiki User Uncleeric - A Surinam or Pitanga Cherry

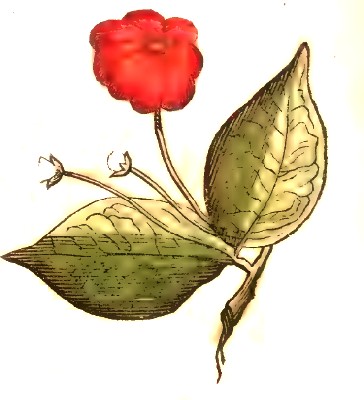

Pitanga

(Eugenia uniflora)

Called by Sailors: Petango

Appears: 1 Time, in 1 Unique Ship Journeys.1

In Author: William Dampier

Type of Ship: Buccaneer

Location Where Found: Salvador, Brazil

Dampier found a fruit he called a petango in March of 1699. This is actually a misspelling of the word pitanga, one of the common names for this fruit, probably made because Dampier only heard the word while in Brazil. There are a variety of other names this plant and it's fruit including Surinam cherry, kerseboom, and, perhaps most impressively, monkimonkikersi.2

Dampier says this is "a small red Fruit, that grow also on small Trees, and are as big as Cherries, but not so Globular, having one flat side, and also 5 or 6 small protulerant

Artist: Albert Eckhout or Frans Post

Pitanga Fruit, Flowers and Plant, From Historia naturalis Brasiliae,(1648)

Ridges... and [it] has a pretty large flattish Stone in the middle."3 Willem Piso described the fruit he found in Brazil where he was serving as the local governor's physician on behalf of the

Dutch West Indies Company between 1637 and 1644 in his book on the plants and animals. He said it was "the size of a berry, round and deeply grooved eight times like a ball... the pulp is covered by a miniature cherry and is succulent... it contains a round stone, not hard and a little compressed"4.

Of the flavor, Dampier says, "'Tis a very pleasant tart Fruit"5. Piso expands upon this a little, explaining that pitangas have "a warm and bitter taste, something of the flavor of a pepper" adding that the pit is sour.6 Neither of them mention how these fruit are eaten. Modern Botanist Tong Kwee Lim says, "Its predominant food use is as a flavoring and base for jams, jellies and relish."7

Being a physician, Piso's comment that the flavor is warm and bitter might be taken to suggest something about the humoral qualities of the fruit. However, this is not explicitly stated and Piso says nothing more about the medicinal properties of pitangas. Botanist Lim says when they are ripe, they are rich in vitamin C. An article about the traditional medicinal uses of plants in Brazil comments that the fruit is acidic and can be made into a syrup to treat influenza.8

1 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 70; 2 Robert A. DeFilipps, Shirley L. Maina & Juliette Crepin, Medicinal Plants of the Guianas (Guyana, Surinam, French Guiana, January, 2004, p. 207; 3 Dampier, p. 70; 4 Willem Piso, Historia naturalis Brasiliae, translated by the author, 1648, p. 116; 5 Dampier, p. 70; 6 Piso, p. 116; 7 Ton Kwee Lim, Edible Medicinal And Non-Medicinal Plants, Vol. 2, 2012, p. 621; 2 DeFilipps, Maina & Crepin, p. 207

Pitomba Fruit - Eugenia luschnathiana

Pitomba

(Eugenia luschnathiana or Talisia esculenta)

Called by Sailors: Petumbo

Appears: 1 Time, in 1 Unique Ship Journey.1

In Author: William Dampier

Type of Ship: Buccaneer/Explorer

Location Where Found: Salvador, Brazil

Dampier is one of the only authors found during this period to mention pitombas. His description is even repeated in another book discussing Brazil which was written decades later.2 However, little else is found regarding this fruit during this time period. He discovered it in Brazil where there are two fruits called by the same name. Today they are classified as Eugenia luschnathiana and Talisia esculenta. Dampier provides a simple explanation of the fruit he found during his stop in Brazil in 1699: "Petumbo's are a yellow Fruit (growing on a shrub like a Vine) bigger than Cherries, with a pretty large Stone: These are sweet, but rough in the Mouth."3

A modern description of Talisia esculenta indicates that it contains "large, oblong seeds, covered by a bittersweet aril [fleshy covering] ranging from white to transparent when

Photo: Jorge Andrade - Pitomba Fruit, Talisia esculenta

the fruit is mature"4. A modern description of Eugenia luschnathiana says, "The skin is thin, tender, and the pulp golden-yellow, apricot-like in texture, soft, melting, juicy, aromatic and slightly acid, faintly resinous in flavor. In the central cavity there may be one round seed or 2 to 4 irregular, angular seeds"5. Of the two descriptions, the second seems slightly more likely, if only because it makes the fruit sound sweeter with just a slight acidity which might make also make it 'rough in the Mouth'. Although, in fairness, the Talisia is described as 'bittersweet'.

Because the fruit does not appear in any of the period botanical books under study, nothing can be said of its perceived medical properties at this time. From a modern perspective Talisia esculenta seeds are said to be "used as antidiarrheal and astringent agents, tea from the seeds is used to treat dehydration, and tea from the leaves is used for backache and for kidney problems."6 Because these are local, traditional treatments, it is not certain if the seeds would have been used in this manner during the golden age of piracy. In any case, it is doubtful any period sailors would have been aware of this.

1 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 70; 2 Atlas Geographus: Or, A Compleat System of Geography, Ancient and Modern, 1717, p. 256; 3 Dampier, p. 70; 4 Franklin Riet-Correa, Cicero W. Bezerra, Marcia A Medeiros et al., "Poisoning by Talisia esculenta (A. St.-Hil.) Radlk in sheep and cattle", Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation, 2014, Vol. 26(3), p. 412; 5 Julia F. Morton, Fruits of warm climates. 1987, p. 392; 6 Riet-Correa et. al, p. 412

Photo: Daniel Di Palma - Seagrape Bunch, Coccoloba uvifera

Seagrape

(Coccoloba uvifera)

Called by Sailors: Grape-Tree fruit

Appears: 1 Times, in 1 Unique Ship Journeys.1

In Author: William Dampier

Type of Ship: Buccaneer/Explorer

Location Where Found: Isla del Carmen, Mexico

Although the name seagrape contains the word grapes, it is actually a member of the buckwheat family being found throughout the Caribbean and Central America.2 John Layfield, 'chaplain and attendant' of George Clifford, third earl of Cumberland, mentions finding them when the earl was in Puerto Rico in 1598.3

Dampier says "the Fruit is as big as an ordinary Grape, growing in Bunches or Clusters among the Twigs all over the Tree; it is black when ripe, and the inside redish, with a large hard Stone in the middle."4

Photo: Daniel Di Palma - Seagrapes, Coccoloba uvifera

Layfield indicates they are wild grapes, but seems unsure of the label when he describes them. He notes they grow in clusters and "like Grapes, they are round, and as great as a good Musket-bullet, and yet have they very little meat upon them, for their stone (if that which is not hard may bee called a stone) is exceeding great for the proportion of the fruit, insomuch that the meat seemeth to bee but the rinde of this stone."5 Physician Hans Sloane, who found them at Port Royal, Jamaica 'and all the Caribes' doesn't refer them as grapes, instead describing them as "Berries, small Plumbs or Myrabolans of the Bigness of an ordinary Raisin of a Bunch of Grapes, having under an outward reddish brown or purplish Membrane, a soft very thin Pulp, covering one large, round Stone, containing a Kernel."6

Regarding the flavor, Dampier says the "Fruit is very pleasant and wholsom, but of little substance, the Stones being so large"7. Layfield says it is soft and can be squashed between your fingers, "but it hath a bitterish kirnell in it, and that which is without it is meat, and that of a delightfull saporous [agreeable] taste."8 Sloan says it is "not unpleasantly adstringent", later adding that "being pleasant, [it] is gather'd and brought to Market in Barbadoes."9

Sloane is the only author to talk about this fruit from a medical standpoint and he says nothing about its humoral value. However, he does note that medicinally, "The Stones, being very adstringent, are used in Fluxes with great Success."10

1 William Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 49-50; 2 "Coccoloba uviifera", wikipedia.com, gathered 7/12/22; 3 Samuel Purchas, Halkluytus Posthumus, Or Purchas His Pilgrimes, Vol 16, 1906, p. 96; 4 Dampier, p. 49; 3 Purchas, p. 96-7; 6 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 2, 1707, p. 129; 7 Dampier, p. 49-50; 8 Purchas, p. 97; 9,10 Sloane, p. 129