Obtaining Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Next>>

Obtaining Food at Sea During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 1

"Without question, equipping and preserving sufficient food and drink on long-distance voyages was intimately tied with the survival of the crew in terms of morale and nutrition and, ultimately, could determine the success or failure of the voyage." (Cheryl A. Fury, "Health and Health Care at Sea", The Social History of English Seamen, 1485-1649, p. 198)

Pirate Edward Low's Men Dining, From

Historie der Engelsche Zee-Rovers (1725)

Food is a topic of monumental importance to all those who made voyages of any significant duration. It had a direct impact on the health and well-being of a crew and was considered a crucial part of those healing from wounds and surgeries during the golden age of piracy.

This is the second of a series of articles which look at food as used by English sailors during the golden age of piracy (1690-1725), broadly dividing them into navy sailors, merchants, privateers and select buccaneers, sailors and pirates. It focuses on the many ways that sailors could obtain food while they were traveling by sea. The first article examines how food was used by the body and looked at the perception of healthiness of food provided to sailors. The third article looks at several formal and informal 'provisioning stations' which were used by various types of sailors. The fourth article looks at victualling and the food consumed by the navy, navy officers, merchants, privateers and pirates. The people and procedures common to all sailors during this period are discussed in the fifth article including an examination of how food was handled, cooked and eaten shipboard.

1 Tyler Allen, "Dining on the high seas", Spirit Magazine, Texas A&M Foundation Website, gathered 9/4/19; 2 See Ed Fox, Piratical Schemes and Contracts, Thesis, 2013, pp. 90-101

Obtaining Food at Sea in the Late 17th and Early 18th Centuries

Artist: Francis Swaine - An English Frigate (18th c.)

Ships under travel preferred to make landfall as infrequently as possible because it extended the journey, particularly when the men were allowed to leave the ship. Vessels sometimes had trouble with men leaving and not returning for various reasons, reducing manpower and even making it necessary for them to try and recruit more. In addition, ships travelling from the old world to the new were at sea for weeks or months, which required them to have sufficient provision to endure such journeys. So strategy was required when to make sure that there was sufficient food on a voyage and that more could be obtained when necessary.

Most of the food consumed by sailors was either dried or salted since these were the most reliable methods for preserving food at that time. The standard English navy diet included salt beef, salt pork, dried or salted fish, ship's biscuit (bread baked twice or more), reconstituted dried peas, oatmeal or oatmeal porridge (also called burgoo), cheese and butter.1 (The details of this diet are presented in detail in the fourth article on sailor's foods.) As discussed in the article on Food Health, elements of this diet were familiar to English sailors and were found among the foods carried by merchant sailors, privateers and pirates during this time period.

Dried and salted provisions could still go bad, become infested

Photo: Wolfgang Sauber - Victual Barrels Below Deck, Vasa Model

with vermin or otherwise be destroyed. Sometimes they were used up before the end of the trip. Most of the sea voyages in the Mediterranean and Orient passed by places where ships could stop to get fresh provisions or recruit more salted and dried foods to continue their journey when the ship's supply was finished or damaged, provided they found cities and villages friendly to the ship's nation. In less developed and established areas such as the New World, English ships often had to fend for themselves. This was complicated by the various wars between England and other countries, particularly Spain; many of the territories in Central and South America were Spanish-held. Here the variety of foods eaten by crews such as explorers, buccaneers, pirates and privateers necessarily expanded based on what they found.

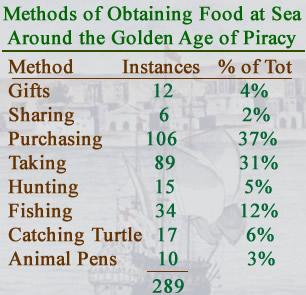

What follows is an examination of the ways ships obtain food during their journeys based on what is found in the sailors accounts from the period. This article examines seven different methods of procuring provisions while a ship traveled, which can be seen in the chart below.

The first section of this article looks at the 12 examples of food being received as gifts, which makes up 4% of the data. This food was usually a very small amount and was given to ship's officers from the rulers of locations

Methods of Obtaining Food at Sea During GAoP

Image Artist: Cornelius de Bruyn, Bandar e-Abbas (1704)

where they stopped to encourage trade or show appreciation. The second section examines 6 examples of ships sharing food, which makes up the least employed method of obtaining food by sailors during this time.

The article next examines the most popular way for a ship to obtain food with the data containing 106 examples of ships and sailors purchasing it. There are examples of each of the five different types of English sailor - naval, merchant, privateer, buccaneer and pirate - purchasing and/or trading for food. Because there are several detailed examples of both buying food and trading it, the two different methods are also discussed.

The second most popular method used by ships is was to take it, either from land or ships. There are 89 examples of this in the sea literature under study with pirates making up the bulk of it with 70 different instances. The rest of the examples of stealing food comes mostly from the privateering and buccaneering accounts.

Three methods for capturing food in remote locations include hunting, fishing and catching turtles. Since ships were at sea, it should not be surprising that there are more than double the number examples of fishing being used to procure food by ships as there are of them hunting on land for food. There are even more examples of Because hunting was such an integral part of the buccaneering trade, that section of the article also includes 5 examples from the accounts of Henry Morgan's forays which are not included in the data calculations presented in the above chart. The last section of the article discusses 10 examples of ships keeping pens of live animals on board to be slaughtered and eaten during the voyage.

1 See Commander R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 254-5