Obtaining Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Next>>

Obtaining Food at Sea During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 7

Obtaining Food at Sea in the Late 17th and Early 18th Centuries - Taking

"...the Pyrates at Sea... know what Latitude to lye in, in order to intercept Ships; and as the Pyrates happen to be in want of Provisions, Stores, or any particular Lading, they cruise accordingly for such Ships, and are morally certain of meeting with them…" (Daniel Defoe [Captain Charles Johnson], A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Shonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 5)

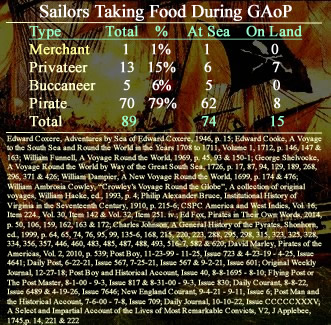

Types of Sailors Taking Food During the Golden Age of Piracy

Image Artist: Ambroise-Louis Garneray - Taking a Ship (after 1852)

Another way of procuring food for some types of sailors was to take it. There are 89 total examples of sailors stealing food either on land or from other ships, making it the second best represented method for sailors to procure food in the accounts under study. While there were no examples found of navy ships doing so, every other type of sailor is represented in the data from around the golden age of piracy.

There is only a single example of a merchant ship taking food which comes from Edward Coxere's account of his time aboard a vessel captained by an Irishman named Tilly around 1650. The crew (and the ship) were Dutch. After they had delivered their cargo to San Sebastian, Spain the ship was hired by the King there to attack French vessels. Tilly's ship had a large number of guns for a merchant - 24 - and since they had been hired by a monarch it could be considered a privateer. However, Coxere identifies it as a merchant so it has been included here as such. Coxere explains that they took a French vessel coming "from Newfoundland with codfish bound home within a day or two sail of his port. This prize [the codfish] we turned into the hold."1 So much for the single example of a 'merchant' taking food.

Artist: Simon de Vlieger - Ships on a Rocky Coast (c. 1640)

The rest of the citations mentioning food being stolen are all buccaneers, privateers and pirates. Because only a few later-period buccaneers are included in the data, they are underrepresented here with 5 examples (6% of the data). Privateers have a stronger showing with 13 examples (15%). Not surprisingly, pirates make up the majority of the examples with 70 instances of them taking food.

The data can also be divided by whether the food was taken on land during a raid or at sea after a ship had been captured and their stores were raided. For the pirates and buccaneers, the majority of the thefts found in the accounts took place at sea. The privateers took food almost equally from land and sea, with only one more land-based food capture than sea-based. Let's examine the data for each category of sailors who took food more than one time.

1 Edward Coxere, Adventures by Sea of Edward Coxere, 1946, p. 15

Privateers Taking Food

All the information about privateers taking food included here comes from three accounts, each of which describes a journey to South and Central America to attack the Spanish after which they sailed across the Pacific to the East Indies to make their way around Africa and back to

Artist: John Clevely the Younger

Privateer George Anson capturing the Spanish Galleon Nuestra Senora de Covadonga (1756)

England. These accounts include: William Funnell's description of Commander William Dampier's St. George and Cinque Ports making the journey between 1703 and 1706, Woodes Rogers' Duke and Dutchess sailing between 1708 and 1711, and George Shelvocke's Speedwell sailing (at times) with John Clipperton's Success between 1719 and 1721.

Funnell's account describes taking food from ships they captured twice and from a land-based location once. The first ship which they stole food from was taken on May 6th of 1704. While he doesn't mention the captured ship's name, he describes it as "a great Ship, of about 550 Tuns. She was deeply laden with Flower, Sugar, Brandy, Wine, about 30 Tuns of Marmalet of Quinces, and considerable quantity of Salt, with some Tuns of Linnen and Woollen-Cloth; so that now we might supply our selves with Provisions for four or five Years."1 Apparently the provisions either didn't last quite that long or they wanted more variety in their diet, because they captured an unnamed Bark near the Bay of Salugua (by modern Manzanillo, Mexico) in December of the same year. In the vessel, "we found some Bacon, Fowls, Bread and Rice, with some Powder and Shot."2 Sometime in the same year, the crew of the St. George captured "an Indian Town, which we called Scuchadero [near modern Sarigua National Park in Panama].

Artist: Howard Pyle

Fanciful Image of Pirates Taking a City (c 1911)

...In it we found store of Dunghil-Fowls [common chickens], Parrots, white and black Beans, Yams, Potatoes, Maiz &c. It consisted of about two hundred and fifty Houses; and round about the Town were great

walks of Fruit, as Plantains, Bonanoes, & c."3

All the descriptions of capturing ships from Woodes Rogers' voyage come from Edward Cooke's account. Cooke has them taking food from a ship one time and from land twice. The first land-based theft of food occurred at Guayaquil, Ecuador in April of 1709. Cooke reported that when the privateers arrived, the city's residents fled to the woods with all their valuables, "leaving their Guns [cannon], four whereof were taken [by the privateers], with considerable Quantity of [corn] Meal, Peas, Sugar, Brandy and Wine"4. The second land-based food capture occurred while they were anchored at Isla Gorgona and some of the privateers went over to the mainland somewhere around Sanquianga, Columbia in July of 1709. They "took the small Village there, and on Wednesday 17, return’d, bringing 7 Beeves, 14 Hogs, some Fowl, about 50 Bushels of Indian Wheat, and a few Goats."5 The single incidence of food being taken from a ship by Rogers' privateers occurred during their stay at Guayaquil. On the ship, Cooke reported there were "330 Bags of Meal, and 140 Arrobas, that is, 25 hundred Weight of Sugar, some Onions, Quinces, and Pomgranates."6

The majority of the examples of privateers stealing food comes from Shelvocke. Of the 7 examples included in his book, 4 have the privateers taking food from land and 3 from ships.

Artist: Eugenio Cajes

La Recuperación de la Isla de Puerto Rico (c. 1634-5)

The first land-based food theft occurred at 'Chacao' (on Chiloé Island, Chile) in December, 1719. The Speedwell had rounded Cape Horn and the privateers needed to restock their supplies. Shelvocke sent thirty men under the command of a Lieutenant Brooks "to take what provisions of any kind he could meet with. ...In the evening the Launch returned, and brought with her a large Piragua [a small, flat-bottomed boat] she had taken, and were both laded with store with sheep, hogs, fowls, hams, barley and green peas and beans"7. The next land capture was at 'Payta' (Paita, Peru) in March, 1720 where the privateers grabbed "hogs, fowls, brown and white Calavances [hyacinth bean], beans, Indian corn, wheat, flour, sugar, and as much cocoa-nut as we were able to stow away"8. An even larger haul was taken from Iquique, Chile in October where Shelvocke explained that they "found a booty more valuable to us, at present, than gold or silver, which consisted of about 60 bushels of wheat Flour, 120 of calavances [beans] and corn, some jerk'd beef, pork, and mutton, 10000 weight of well cur'd fish, a good number of fowls, some rusk, and 4 or 5 days eating of soft bread"9. The last example comes from the capture of Coibita Island in January of 1721. "We took all their provisions, which consisted of a little pork, and some green, ripe and dry'd plantains, there was a large quantity of the latter, which being pounded made a grateful flower to the taste"10.

The first of the Shelvocke's sea-based captures of food occurred in December of 1719 at the Bay of Concepcion (modern Tulcahuano, Chile), although the vessel taken "had a very small cargoe on board, which consisted of sugar, molossus, [and] rice"11. The next ship captured was the

Artist: Samuel Scott

Charles Wager's Assault on the Spanish Treasure Fleet

in 1708 (18th century)

Spanish Conception de Recova "of the burthen of 200 ton, [which was] laden with Flour, Loaves of Sugar, Bales of Boxes of Marmalade, Jars of preserv'd Peaches, Grapes, Limes, &c."12 The last example of taking food from ships which is found in Shelvocke isn't a really a specific capture, rather it is advice he gives to those who would follow him on privateering voyages about procuring food from ships bound to the cities on the coast of Peru:

If on this coast you should want provision, you can't well miss of finding enough (for a single ship at least) on the Island of Iquique [this is the name of a city on the coast of northern Chile, however Shelvocke may be referring to some other island]; for they having nothing of their own growth, are obliged to keep a stock before-hand for the Inhabitants; for the same reason you may meet with it at Payta… From the road of Guanchaco [Huanchaco, Peru], the port for Truxillo [Trujillo, Peru], they likewise export great quantities of wheat, flour, bread, wine, brandy, sweetmeats and fruits, plate, &c. these ships generally trade to Panama; the same trade is carried on from Guayaquil to the same place.13

Of the three primary types of sailors who took food during the golden age of piracy, privateers are the only ones who got more of it from land-based captures than they did from ships. This should not be entirely surprising given that their letters of marque gave them permission to attack ships and colonies of Spain. In this regard, Shelvocke's account is particularly telling; he several times talks about the lack of food they had while sailing along the west coast of South and Central America. Being unfriendly waters, they would have had to take food whereever and whenever they could get it.

1 William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 45-6; 2 Funnell, p. 93; 3 Funnell, p. 150-1; 4 Edward Cooke, Voyage to the South Seas, 1712, p. 146; 5 Cooke, p. 163; 6 Cooke, p. 147; 7 George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 94; 8 Shelvocke, p. 189; 9 Shelvocke, p. 268; 10 Shelvocke, p. 296; 11 Shelvocke, p. 129; 12 Shelvocke, p. 371

Buccaneers Taking Food

Only three buccaneer accounts are included in this survey, all of them taking place in the 1680s right

Ships Landing at Cape Francois, From Naaukeurige versameling

der gedenk-waardigste (1706)

before the golden age of piracy. Like the privateer accounts, two of these occurred during voyages to which went first to South and Central America and then sailed across the Pacific to the East Indies and around the Cape of Good Hope and back home to England. These include: William Ambrosia Cowley sailing on the Revenge and Nicholas (1684 to 1686) and William Dampier on the Revenge and Cygnet (among others) between 1680-1691. The other buccaneer account is from the writings of Basil Ringrose who was sailing with buccaneers Bartholomew Sharp, Richard Sawkins and various others around South and Central America from 1680 through 1682. He did not cross the Pacific on his journey, returning to England by sailing back around Cape Horn.

Two examples of buccaneers stealing food from ships are found in Ringrose's book. The first occurred at Coiba Island in Panama on May 25, 1680 where Ringrose reports that Sawkins and Sharp "took a Bark [barque] at the Rivers mouth loaden with Montego and Indian Corn. As affairs were now with us, we took this for good Provisions, and so returned to our Ships"1. The second comes occurred on July 30 of the next year when captain John Cox on the May-flower and Sharp on the Trinity captured a Spanish vessel near Cape 'Passado' (near modern Bahia de Caraquez). Ringrose explains, "The Prize [ship] was loaden with Wine, Brandy, Oyl, and Fruit... [from which we] stored our selves with Wine and Brandy, and considering our small number of Men left, and good stock of Provisions, we thought it best to return home with what Booty we had"2. Unfortunately for them, they left behind 670 'piggs' (olbong bars) of what they thought was tin, but which they later learned was silver!

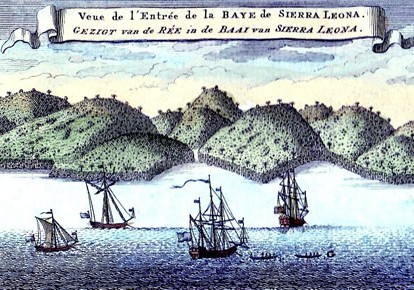

Cowley only mentions one food capture, also taken from a ship in 1683 by Captain John Cook's ship Revenge on the coast of Africa as it was headed for South America. Cook says, "we arrived upon the Coast near Cape Sierra Leone,

Cartographer: Jaques Bellin -Map Detail Showing Bay of Sierra Leone (c. 1750)

we alighted on a new Ship of 40 Guns, which we boarded and carried her away. We found she was very fit for so long a Voyage, for she was well stored with good Brandy, Water, Provisions and other Necessaries."3 The ship was a Dutch slaver which they decided to call Batchelor's Delight.

Dampier's account includes two examples of provisions being procured from captured vessels. The first occurred when they were at Gorgona Island off Columbia in 1685 where the buccaneers "rummaged [their] Prize, and found a few Boxes of Marmalade, and three or four Jars of Brandy, which were equally shared between Capt. Davis and Capt. Swan, and their Men."4 The prize was a 90 ton Spanish vessel headed for Panama City. The other mention of a specific food capture was a small prow captured in April of 1688 near Sierra Leone which "was laden with Coco-nuts, and Coco-nut Oil. Captain Read ordered his Men to take aboard all the Nuts, and as much of the Oil as he thought convenient, and then cut a hole in the bottom of the Proe [prow], and turned her loose, keeping the Men Prisoners."5

Every one of the accounts of buccaneers taking food included here occur during ship captures, which is interesting give that buccaneers were usually known for their land-based attacks. There are a couple of possible reasons for this. First, the earlier raids by Morgan and his contemporaries who were known for their land attacks have not included in the data. Second, late period buccaneering was something of a transition from land-based to sea-based attacks. Finally, the accounts in use here do not mention many food captures in their descriptions and more of them than are mentioned would have occurred. Those noted must have been a small sample of the many food captures these buccaneers would have made during the years they spent at sea, but this article only includes accounts which specifically mention buccaneers taking food.

1 Basil Ringrose, The Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp, And Others, in the South Sea, 1684, p. 17; 2 Ringrose, p. 88-9; 3 William Ambrosia Cowley, "Cowley’s Voyage Round the Globe", A collection of original voyages, William Hacke, ed., 1993, p. 4; 4 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 174; 5 Dampier, p. 475