Obtaining Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Next>>

Obtaining Food at Sea During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 3

Obtaining Food at Sea in the Late 17th and Early 18th Centuries - Purchasing

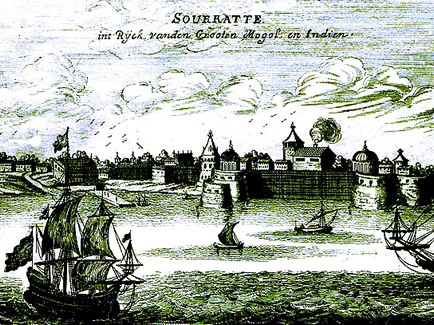

Background Image Artist: Theodor de Bry

Harbour Scene Lisbon, From America, Part 3 (1593)

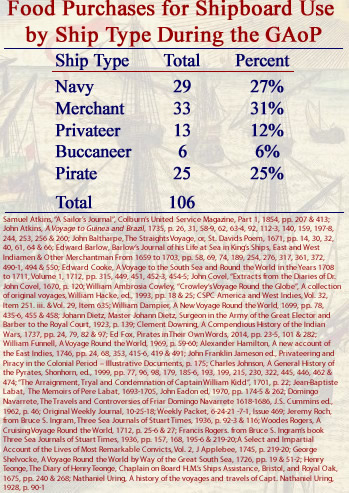

Of all the methods of obtaining food at sea, the one with the most support is purchasing it, either by using cash or via trading. There are 106 examples of sailors purchasing food for use shipboard in the period and near-period books under study with examples from each of the five different types of English sailors. A breakdown can be seen in the chart at left. The percentages are shown for reference only. It should be pointed out that the value of the percentages is limited by the number of sources for each ship type. For the navy, there are 8 different ships, for merchants there are 21, for privateers there are 4, for buccaneers only 2 and for pirates there are 16 different vessels.

Navy

The majority of the food purchased during a journey by the navy are instances of the men on the ship purchasing food for themselves; of the 29 accounts where the navy purchases food, 19 are of them are individuals purchasing food with 6 coming from John Baltharpe and 7 from John Atkins.

Baltharpe was the author of an amusing poem about the journey of HMS St. David which traveled from England to the Mediterranean between May of 1669 and April of 1771. While at Rota, Spain in August, 1669, he explained "The Spaniards brought us Wine A-board, Bread, Grapes, Fig-cheeses they aford, Either for Money or Truckar [trade]"1. He gives similar accounts for stops made near Alicante, Spain in December of 16692, Livorno, Italy in January of 16703, Messina in both March4 and November5 of 1670 and Naples in October of that year.6 Messina seems to have been particularly bountiful; in May they offered the sailors cabbages, nuts, figs, eggs and wine and in October they offered cabbages, carrots, turnips, nuts, lemons, oranges, figs eggs, wine, beer and ale.

Sailor Edward Barlow, who was stationed on

Artist: Adriaen van Diest

A British Fifth Rate Signalling Its Arrival ( c1673-1704)

several navy vessels during his forty four year career talks about purchasing food while serving aboard the fifth rate HMS Augustine on her journey in the Mediterranean in 1661. At Algiers, he observed that they had good figs, "plenty of oranges and lemons and ‘pumgarnates’ and some dates and plenty of roots [onions], and plenty of beef and mutton and ‘cabereto’ [goat’s-flesh]."7 While visiting Spain, he says that although the crew was on short allowance (meaning six men were served the amount of food normally given to four), "we made ourselves as merry as we could, buying some wine and such things as the Spaniards brought on board to sell, such as bread and wine and oranges and lemons, and some roots, as radishes, which they have all the year long."8 He also said that provisions were cheap in Pembroke, Wales, focusing particularly on the goodness of their corn and "the best ale brewed there that I have drunk in all my life, to my thinking, both in strength, colour and taste."9

Another example of navy sailors purchasing food is recorded by Jeremy Roch when HMS Charles Galley was in Dorset on July 25, 1689. "I took the opportunity of viewing the Island of Portland [off Southill, England] where I bought some dried fishes and so aboard again."10 Two instances of regular navy sailors buying food for themselves come from Samuel Atkins' Journal of his time aboard the Crown in the Mediterranean in 1681. The first is when the ship was at Naples, Italy in May or June of 1681 which was "abounding with all sorts of provisions, espetially ffruit, which is very cheap and extraordinary good"11.

Artist: Jan Brueghel the Elder

The Great Fish Market (1603)

The other account makes it a little less clear who was doing the purchasing. The Crown was at Ventotene, Italy where they "went into their cove to ye ffish potts, and bought a sort of ffish like bream, but large, and as good just as any fish I ever eat."12 It is possible this may have been purchased by the purser to feed the ship since fresh fish was an allowed substitute in the Mediterranean. At this time, navy pursers were a little less restricted in how they could supply their ship in foreign ports than they were during the golden age of piracy.

Of the 7 accounts of the navy purchasing food found in John Atkins' book, several clearly note that it was bought by individuals. While HMS Swallow and Weymouth were at Cape Montzerado (present-day Monrovia, Liberia) in the spring of 1721, Atkins says that the land-based traders were wary, "coming off every day in their Canoes, and then at a stand [stop, deciding] whether they should enter [the ship to trade with the navy sailors]."13 (The natives were afraid of being 'panyarred' - having their goods stolen from them when they were aboard or, worse, being taken prisoner to be sold as slaves.) He reports a similar situation at Cape Lopez in what is today Gabon, Africa in early 1722, with "few of them [local natives] venturing on board a Ship; scared, I suppose, by the Tricks have formerly been put upon them by our Traders: so that we barter altogether on shore, where they attend for that purpose."14 Whatever else these accounts suggest, it is fairly clear that the navy sailors were trading with the natives. Similarly, when the Weymouth stopped at Hispaniola (Dame Marie, Haiti), he explains "we bought some jerked Hog's Flesh from Jamaica", again indicating individual purchases.15

The rest of Atkins' accounts are less clear about whether the buyers were individual sailors or the navy porters buying for the ship. These include purchases made at the Portuguese islands at Madiera16, Sesthos (Cape Palmas, Liberia) in May of 172117,

Cape Palmas, Africa (1853)

Cape Corso (Ghana) in November of that year18 and several other locations along the African coast in 172119. In most of these accounts, Atkins simply lists items that were for sale, often noting the price in money or trade. However, two of them contain more information which suggests that when he listed prices, he was talking about purchases by sailors. The first is the situation at Cape Lopez. Atkins explains that "the Country affords Plantains, Goats, Fowls, and particularly grey Parrots, all cheap; but their principal trading Commodities are Wax in Cakes, and Honey, exchanged with us on easy terms"20; the phrase of interest being 'exchanged with us'. The second is the trade at Sesthos where, in one part of his text, he gives the generic list of trade items, advising "Here may be purchased considerable Quantities of Rice; the River abounds with Fish; and you are tolerably supplied with Goats and Fowls"21. In another he specifies, "A 2 pound Basin buys a Goat; and I purchased two for an old Chest, with a Lock to it."22 With these examples in mind, the other two entries containing similar listings of food items have been included with the individual naval purchases.

There are two examples where the purchase of food appears to have been for the ship's officers' mess, both coming from chaplain Henry Teonge's account of his time in the navy. In the first, HMS Bristol was near Dogger's Bank (a sandbar off the east coast of England), where "we found two boats fishing, and bought of them

Bristol Harbor (1850)

ling and fresh cod of four foot in length for 6d. [pence] apiece; bret and turbot for 2d. apiece: cheap enough."23 While it is not entirely clear whether this fish was for the whole ship or just the officers, Teonge's focus is generally on what the officers ate. When the Bristol was in Almyra Bay off Malaga, Spain in December of 1678, Teonge states: "I went with our Captain to the town-side, but they would not give us leave to come ashore. But they brought to us good wine, lemons, oranges, pome-citrons, sheep hens, eggs, coleworts [arugula], etc., and sold them cheap enough."24 Based on what was purchased, this is almost certainly food for the officers on the ship.

The rest of the examples of the navy purchasing food all are classified as food purchased for the ship rather than the officers or individuals. There are 8 of these. One comes from Baltharpe's poem which explains that when the St. David was in Messina, Spain in November of 1670, "Of our Comrades [a Newfoundland fleet] we did get Fish, Which we do look on as brave Dish... I know no Breakfast meat more fitter."25

The balance all come from Atkins' accounts, which are rather vague about what the purpose for which food was procured. This makes sense because his purpose in mentioning provisions that could be purchased was in no small part to make his book as useful a guide as possible to to those ships who sailed to the same places (particularly merchant vessels). As he explains of Santiago in the Cape Verde Islands, the locals "welcome all sort of Ships (of good, or ill Design) bound to Guinea, India, Brasil, or the West-Indies; they frequently putting in here to furnish themselves with fresh Provisions"25. Such a statement could be legitimately applied any of the five types of sailors discussed here. Since sailing on a navy ship, however, this information is included in the navy category.

Before he published his own book, some of Atkins's information about Africa, the West Indies and Brazil made its way into Charles Johnson's General History of the Pirate in the section about Howell Davis. This is included as background information by Johnson, suggesting that the food listed could be purchased by ships stopping in the locations being discussed. Of the locals on São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón Atkins said, "they come to us in Way of bartering, very cheap", going on to list prices in either money or trade.26 He explains that on Principe there were "fruitful

Ship from the Frontispiece of John Atkins' Book

A voyage to Guinea, Brasil, and the

West-Indies (1735)

Plantations of Yamms, Kulula, Papas [Paw paws, Asimina triloba], Variety of Sallating [Salads], Ananas, or Pine-Apples, Guavas, Plantanes, Bananas, Manyocos, and Indian Corn; with Fowls, Guinea Hens, Muscovy Ducks, Goats, Hogs, Turkies, and wild Beefs... [which the slave caretakers] exchange or sell... for Money"27.

In a similarly encompassing manner, hinting that he was providing information to captains heading to the same location, Atkins says in his own book, "Provisions are plentiful above any place on the whole Coast [Cape Corso (Ghana) to Whydah (Ouidah, Benin)], but neither very cheap nor large."28

Atkins does provide two examples that more directly suggest food was being purchased for the ship rather than by individuals or officers. The first comes from a stop in September of 1721 where he explains that they "touched at St. Thome [São Tomé], the chief of these Portuguese Islands for fresh Provisions, purchased cheap"29. The second is from Jamaica in 1722, where he notes that "our Ships [the Swallow's and Weymouth's] Companies [were] being victualled here twice a Week with fresh Beef, during a stay of 6 Months"30. At this time, navy crews who were in port were to be provided with fresh beef twice a week, almost certainly what he is talking about.

1 John Baltharpe, The Straights Voyage, or, St. Davids Poem, 1671, p. 14; 2 Baltharpe, p. 30; 3 Baltharpe, p. 32; 4 Baltharpe, p. 40; 5 Baltharpe, p. 64; 6 Baltharpe, p. 60; 7 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 58; 8 Barlow, p. 69; 9 Barlow, p. 74; 10 Jeremy Roch, from Bruce S. Ingram, Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 127; 11 Samuel Atkins, "A Sailor's Journal", Colburn's United Service Magazine, Part 2, 1854, p. 413; 12 Samuel Atkins, Part 1, 1854, p. 207; 13 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 59; 14 Atkins, p. 197-8; 15 Atkins, p. 253; 16 Atkins, p. 26; 17 Atkins, p. 63; 18 Atkins, p. 159; 19 Atkins, p. 256; 20 Atkins, p. 197; 21 Atkins, p. 256; 22 Atkins, p. 63-4; 23 Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, Chaplain on Board H.M.’s Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, 1675-1679, 1825, p. 240; 24 Teonge, p. 268; 25 Baltharpe, p. 66; 25 Atkins, p. 31; 26 John Atkins/Daniel Defoe (Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Shonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 179; 27 Atkins/Defoe (Charles Johnson), p. 185-6; 28 Atkins, p. 112; 29 Atkins, p. 140; 30 Atkins, p. 244

Merchant

Almost a third of the instances of purchasing food (33) come from the merchant vessel accounts. A lot of the merchant traffic account from this period tend were from voyages to the East Indies with stops along the way. There are also some Mediterranean and European voyages as well as a single West Indies voyage which mention procuring food.

Gravesend, From A new display of the beauties of England (1776)

Several accounts from northern Europe mention obtaining food there. When Jeremy Roch was sailing his small boat in July of 1677, he reached Gravesend, England where, "I had a mind to get some drink of the fisherman, who also wanting bread, we exchanged one for the other and then kept company with him unto Barking, where the good old fisherman treated us with fish and we filled his head and guts with drink, so after a sound nap and good breakfast we took leave."1 While aboard the west indiaman Guannaboe in 1678, sailor Edward Barlow explained that when the ship was near Dartmouth, they "meeting some fishers’ boats, we bought some fresh fish of them"2. This was apparently for the upcoming voyage.

Kinsale, Ireland is mentioned by sailors Edward Barlow who visited in 1702 and Francis Rogers in 1703. Barlow arrived aboard the East Indiaman Wentworth and he noted that "good provisions were very cheap then in Ireland", being so impressed with them that he listed the price of a variety of goods.3 Francis Rogers said the city "hath a very good market where is plenty of provisions of all sorts."4 He seems to have been similarly impressed with the prices because he goes on to list the cost of several items.

Two sailors who visited other northern European locations where they procured food. Barlow was at Texel, Netherlands in the merchant ship Fflorentine in 1670 where "they loved good drink very well, and tobacco, and for two or three pipes of that, they would give us four or five great lobsters, each of them if they had been in London would have been worth two shillings the

Artist: Ludolf Backhuzen

Merchant Ship Anchorage off Texel Island, Netherlands (1665)

piece"5. While sailing with a whaling ship in the late 17th century, German surgeon Johann Dietz said that they gave the natives in Iceland, "brandy and tobacco from our small store, which to them was highly acceptable. In return they brought us reindeer milk and cheese, dried fish and smoked eel and salmon, a considerable quantity of furs, and some whalebone and other matters"6.

Another (fairly) nearby destination was the Mediterranean. Several English merchant ships made trips there and three different period and near-period authors mention purchasing food. Edward Barlow reported that the merchant vessel Marygold ('Marey gould') was in Naples, Italy in 1676 where "Provisions of all sorts are indifferent cheap"7. While a passenger on the merchant vessel St. Paul, French priest Jean-Baptiste Labat provided a description of how sales were made to such vessels in Cadiz harbor in 1706: "The fishermen and other people who always come alongside a ship when she arrives in port did not fail on this occasion to offer us goods for sale, for the Spaniards suppose that any vessel coming from a long voyage must be short of everything."8 Labat and some of the other passengers had brought quite a bit of food with them, however, and the Spanish were only able to sell them fresh fruit. The third instance of food purchases by merchants in the Mediterranean comes from reverend John Covel who was aboard the London Merchant when it stopped at Tunis, Tunisia in 1673 for water. He explained that the sailors "went on shoar at the watering-place, where were come down many country people"9 with goods for sale. He supplies an extensive list of the fresh food for sale there, noting that, "Every ship stored themselves from hence with what they wanted of sea provisions."10

Merchant ships going from England to both the East and West Indies traveled down the west coast of Africa, often refreshing their food supply by stopping at islands along the way. The Spanish-held Canary Islands were one such destination. When the merchant ship Joseph Galley came into Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Canaries in 1710, Nathaniel Uring reported, "As soon as we landed, we let the Inhabitants know that we wanted some live Cattle; they soon brought down Droves of several Kinds, of which we furnish’d our selves with as many as we had Occasion for, at easy Rates"11.

Cochon Boucanné, On the Spanish Main, By John Sasefield (1906)

Navy sailor Clement Downing was in the same place eleven years later aboard HMS Salisbury "to refresh the Ship's Company with such Provisions as the Place afforded; which were Fowls, Coconuts, Plantanes, Bananas, Pine-Apples, Hogs, and some Goats"12. In 1721 Navy sailor John Atkins reported that Sesthos (modern Cape Palmas, Liberia) was a place where "most of our windward Slave-ships stop to buy Rice"13.

There is only one account of a merchant ship buying food in the West Indies in this literature and that comes from Father Labat. He was aboard the Aventurierre barque around February of 1701 when it anchored off by Tortuga Island (north of modern Haiti). In his usual descriptive style, Labat explains, "I went ashore with a couple of men to ascertain if there was anything to fear, and returned with two hunters, who gave us fresh pork and cochon boucanné [barbecued pork] while we regaled them with wine and brandy. We made a bargain with these hunters to supply us with 1,800 pounds of smoked meat, and 300 pounds of mantegne, or pig’s fat."14

The rest of the merchant food purchases (20 in number making up 60% of the merchant data) all refer to stops in the East Indies. Of course, the East Indies during this period comprised a large area including the Arabian Peninsula, the shores of the Indian subcontinent and the Orient.

Artist: David Roberts

Bazaar in the Streets of Cairo (1838)

The volume of citations suggests the importance of this area for merchant voyages during the golden age of piracy. (However, it also points to how few accounts we have of merchant vessels to the West Indies where there was also thriving trade during this period.)

Three locations on the Arabian Peninsula are mentioned in conjunction with food stops by merchant ships. The first is Zeyla (modern Saylac, Somalia) where merchant sailor Alexander Hamilton reported that "the Natives will bring off Sheep, Goats, Hens, Fish and Fruits to Shipping that sometimes ly becalm'd on their Sea, near the Shore."15 Hamilton served in various capacities in the East Indies beginning in 1688 and throughout most of the golden age of piracy. Of 'Muskat' (Muscat, Oman) he says, "it has as good Markets for Wheat, Barley and Legumen, and for excellent Fruits, Roots and Herbage, and good Cattle, both great and small, as any where in India... the Sea furnishes them with Plenty and variety of excellent Fish. Their Cattle look to be very lean, but when killed, they are very fat and good"16. The third sea-based food stop comes from Francis Rogers account of the merchant vessel Arabia which was at the city of Aden (in modern-day Yemen) in July of 1702. Rogers notes, "The Buzza [Bazaar] of this city is large, containing abundance of stalls and shops, where is sold everything the city and adjacent parts affords, as provisions, fruits, drugs, apparel of all sorts used with them".17

The nation most mentioned as a location to get food in the merchant accounts is India with 9 stops. Locations visited include the modern cities of

Artist: Jacob Peeters - Surat, India Harbor (1690)

Belekeri18, Belopatan19, Hoogly20, Karwar21, Mumbai22, Nancowry Island23 and Surat.24 Fresh fish seems to have been readily available to sailors from local fishermen throughout India; sailor Edward Barlow mentions this while visiting Belopatan in 167025, Karwar in 168528 and Belekeri in 169727 while navy seaman Clement Downing aboard navy provided guard ship HMS Salisbury for an East India merchant fleet says the same thing during a stop at Bombay (today Mumbai) in 1716.28 Other cities provided more in the way of provender. While aboard the merchant ship Recovery in 1683, Barlow found "fowls, as hens and cocks, sometimes for the value of a penny a piece" at Hoogly.29 Hamilton advised that at Nancowry Island in the Nicobars, "The People come thronging on board in their Canoaes, and bring Hogs, Fowl, Cocks, Fish, fresh, salted and dried Yams, the best I ever tasted, Potatoes, Parots and Monkies, to barter"30. Three merchant sailors mention Surat as a stopping place for victuals during the golden age of piracy: Barlow aboard the East Indiaman Scepter in 169731, Francis Rogers on the Arabia in 170232 and Downing on the Salisbury in 1722.33 Rogers explains that the city is "very famous for its trade as any in India, the country about it abounding in cattle, poultry, grain, fruits, drugs, etc"34. Even so, the other two authors only mention purchasing meat and bread while there.

The remaining East India food stops are all found in southeast Asia. Three of them come from Alexander Hamilton's time in the orient. He mentions buying deer in Myanmar35, cows at Rembang, Java36 and casks of salted pork prepared by the people of Bengkalis, Sumatra.37 He speaks favorably of the meat quality he purchased at each location. The last East Indies merchant vessel comes from an account by priest Domingo Navarette who reported that the ship on which he had passage stopped at the Philippines, "A small Vessel made up to us; we lay by for it, to take in some Refreshment"38. Unfortunately, he doesn't say what was purchased.

1 Jeremy Roch, from Bruce S. Ingram, Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p.92-3; 2 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 317; 3 Barlow, p. 550; 4 Francis Rogers, "The Journal of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, Bruce S. Ingram ed., 1936, p. 195; 5 Barlow, p. 254; 6 Johann Dietz, Master Johann Dietz, Surgeon in the Army of the Great Elector and Barber to the Royal Court, 1923, p. 139; 7 Barlow, p. 276; 8 Pere Jean-Baptiste Labat, The Memoirs of Pére Labat 1693-1705, 1970, p. 29; 9,10 John Covel, "Extracts from the Diaries of Dr. John Covel, 1670-1679," Early Voyages and Travels in the Levant, edited by J. Theodore Bent, 1893, p. 120; 11 Nathaniel Uring, A history of the voyages and travels of Capt. Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 242; 12 Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 79; 13 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 62; 14 Labat, p. 174-5; 15 Alexander Hamilton, British sea-captain Alexander Hamilton's A new account of the East Indies, 17th-18th century, 2002, p. 24; 16 Hamilton, p. 68; 17 Francis Rogers, p. 168; 18 Barlow, p. 490-1; 19 Barlow, p. 189; 20 Barlow, p. 361; 21 Barlow, p. 372; 22 Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 24; 23 Hamilton, p. 419; 24 Barlow, p. 494, Downing, p. 24 & Francis Rogers, p. 179; 25 Barlow, p. 189; 26 Barlow, p. 372; 27 Barlow, p. 490-1; 28 Downing, p. 24; 29 Barlow, p. 361; 30 Hamilton, p. 419; 31 Barlow, p. 494; 32 Francis Rogers, p. 179; 33 Downing, p. 97; 34 Francis Rogers, p. 179; 35 Hamilton, p. 353; 36 Hamilton, p. 419; 37 Hamilton, p. 415; 2 Domingo Navarrete, The Travels and Controversies of Friar Domingo Navarrete 1618-1686, 1962, p. 46